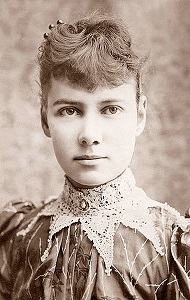

Elizabeth “Nellie Bly” Cochrane Seaman, Intrepid Journalist

“Journalism”, as a concept, is an entirely new development of the last several centuries. Before the printing press led to mass literacy and the desire for “news”, there was no need for people to go and find it out. Over time it evolved, and as the power of this new profession became apparent it attracted those who saw it as a way to change the world for the better. One of the first such journalistic heroes was Nellie Bly.

She was born in 1864 as Elizabeth Jane Cochran in the town of Cochran’s Mills, Pennsylvania. As you might guess from the name, her family were kind of a big deal in the area. Her grandfather Robert Cochran had emigrated from County Derry around seventy years earlier to Baltimore in Maryland. He and his wife had moved to the small town of Apollo in Pennsylvania after their marriage, and that’s where Michael Cochran was born. His father died only a few years after his birth, so young Michael’s mother Catherine raised him alone. She did a good job of it; and Michael became an accomplished blacksmith who was well-liked in the local community. By the age of thirty he had been elected a justice of the peace and he remained involved in state politics. In 1845 he bought a run-down mill and the land around it, and built it up into a successful community. The surrounding town was renamed from Pitt’s Mill to Cochran’s Mills in his honour.

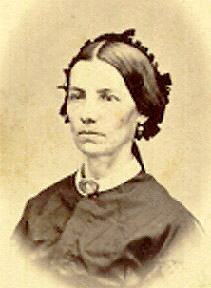

Elizabeth’s mother Mary was Michael’s second wife, and he already had ten children from his first marriage. Elizabeth was the third of five from the second. Elizabeth was a lively child, who got the nickname of “Pink” (or sometimes “Pinky”) from her fondness for wearing the colour. It was an idyllic life, until tragedy struck in 1870. At the age of sixty Michael Cochran died suddenly. It was a shock to everyone, and it was sadly unsurprising to find out that he had left no will. After two months in the courts it was decided that (in accordance with the law) a third of his estate went to Mary, while the remainder was split equally between his children. Since Elizabeth was only six, she was appointed a guardian to manage her funds. The court chose Colonel Samuel McCartney Jackson, a local hero of the Civil War.

Mary was left to raise her children by herself, but in 1873 she fell prey to a charming Civil War veteran named John Jackson Ford. Jack (as he liked to be called) was a widower with no children. He was also an abusive drunk, something which he hid up until Mary had said her vows. Once they were married he showed his true colours, threatening and beating Mary until she became fearful for her life. In 1878 she finally reached her limit and she filed for a divorce. This was a risky move, as divorce was not usually well accepted by the community. However they all liked Mary and disliked Jack, and there was no shortage of people willing to come forth and testify on Mary’s behalf. Despite this (and despite Jack fleeing the town in disgrace) it took a long year of judicial inquiry and second-guessing before her divorce was granted.

The fourteen year old Elizabeth had to testify on her mother’s behalf during the divorce, and the whole ordeal had a great effect on her. She saw first-hand how powerless women could be against men who would ruin their lives. Like her father in his youth, she determined to make her own way. She decided to become a school teacher, and enrolled at the nearby Indiana State Normal School. Her guardian, Colonel Jackson, assured her that her inheritance would cover her tuition. So she enrolled with a clear heart, [1] and dove into a world of learning about writing and art with joy. She was much less happy when she finished her first semester and found that there was not enough money left to pay for her to return. She was very displeased with Colonel Jackson for what she regarded as mismanagement of her funds.

When Elizabeth was forced to drop out of school, her mother made the decision to move the family to Pittsburgh. Two of her sons had already found work there, and Mary set up home with them. She opened a boarding house, and Elizabeth either worked there or in odd jobs in order to help with the household finances. It seemed that she was at a dead end, but then salvation came in an incredibly unlikely form. The Pittsburgh Dispatch published a regular column by Erasmus Wilson, and in 1885 he wrote an opinion piece that got Elizabeth fuming. The theme of his article was women’s rights, and how he didn’t believe in them. A woman’s place was in the home, he wrote, and it was “a monstrosity” for a woman to earn a living. Having a bit more lived experience of why women needed to be able to earn an independent living, Elizabeth wrote a furious letter to the editor. Signed “Lonely Orphan Girl”, it was high on passion and personal context, and low on writing expertise. But editor George Madden was impressed by both the unique voice of the writer and the way she marshalled her arguments. He put a note in the paper asking for “Lonely Orphan Girl” to get in touch with the newspaper. So Elizabeth did.

It turned out to be the best decision she’d ever made. She found Madden sympathetic to her views, and surprisingly also found Erasmus Wilson to be a much nicer person than she’d thought. His article had been written more from thoughtless privilege than from dogmatic malice, and her account of her life had swayed him over to her side. The two actually became good friends, something Elizabeth would never have predicted. The real meat of the meeting came in the form of an offer of work from Madden. He offered her a “right to reply” on Wilson’s column. If her article was good enough to publish then he’d pay her, and possibly offer her future work. Elizabeth went home and wrote The Girl Puzzle, which became her first published work. In contrast to Wilson’s airy certainties, Elizabeth wrote about the real struggles that real women faced, and concluded with a fiery call for women to be given the same opportunities as men:

How many wealthy and great men could be pointed out who started in the depths but where are the many women? Let a youth start as errand boy and he will work his way up until he is one of the firm. Girls are just as smart, a great deal quicker to learn; why, then, can they not do the same?

Madden liked the article enough to ask Elizabeth if she had any other ideas for things she could write about. There was one subject that she felt just as passionate about, given her family’s rough experience – divorce. Her second article was called Mad Marriages, and drew on her experience of her mother’s ordeal to speak to the women trapped in abusive relationships throughout the country. Her family had the fortune to be well-off enough to afford a divorce, and had enough social capital to survive the aftermath. Many were not so lucky. This article is also significant as being where she took on her famous name. Her first article had been as “Lonely Orphan Girl”, but now she needed to choose a more permanent pen name. One of the other writers at the newspaper suggested “Nelly Bly”, the name of a song popular at the time. One spelling error later and Elizabeth Cochrane became Nellie Bly, girl reporter.

Following on from this, Nellie was hired as a staff writer to create a series of articles about the lives of the women working in Pittsburgh’s factories. This was followed by more articles, often spinning out from conversations with the boarders in her mother’s house. Nellie’s feminism and belief in worker’s rights shone through in many of her articles, earning her a loyal following. However this also earned the ire of factory workers and conservatives, who put pressure on Madden to rein her in. He canceled her column, and told her that she would have to cover the more traditional woman reporter subjects of fashion and nature. Nellie was decidedly not okay with this. Instead she proposed a somewhat different idea. She had recently found out from one of the boarders that it was now possible to take a train from Philadelphia all the way to Mexico City. So she offered to travel down to Mexico and become a freelance foreign correspondent. Madden was somewhat apprehensive about the idea, but Nellie convinced him. And off to Mexico she went.

Nellie didn’t go to Mexico alone, though. Her mother Mary came along as a chaperone and companion. She spent six months there, writing articles that Madden published under the title Nellie In Mexico. The unusual subject matter meant that many other papers around the country picked them up for syndication, and Nellie became quite famous. Nellie wrote mostly of food and local customs, including several articles about bullfights that she saw or had described to her. She avoided politics for her own safety, though she was indiscreet enough to mention that one of her local journalist friends had been arrested for criticizing the government. Of course, by doing so she was herself criticizing the government. When word reached her that officials had been asking about her, she decided to pack up and return to Pittsburgh. There she started writing about Mexican corruption in earnest. She wrote about censorship, bribery and the incompetent tyranny of the unfairly elected government. Her columns were later collected into her first published book, Six Months in Mexico.

Having shown a flair for descriptive writing, Nellie was put on to the arts and culture beat for the Pittsburgh Dispatch. However she soon grew bored, and one day suddenly quit. She had decided to move to New York and see what she could do there. She was full of confidence, but she found it a lot harder to break into the deeply chauvinistic New York media scene. Unable to find work, she did some freelance articles for the Dispatch. That gave her an idea, and she wrote an article for them about the New York newspaper scene. That got her into those newspapers to interview the editors, and all of them wanted to see the article when it was done. It got her some contacts on the scene, and a foot in the door. But it would take a bold audacious move to really establish her. Luckily she had one in mind.

Nellie went to see John Cockerill, editor of the World. It was one of New York’s most prestigious papers, but John knew Nellie from her interviews and so she was able to get an appointment. She pitched him her idea: that she sail to Europe and then return in steerage class, in order to write an article about the conditions that poor immigrants endured in order to reach America. John wasn’t sold on the idea, but he liked Nellie’s enthusiasm. He promised to take her proposal to Joseph Pulitzer, the legendary owner of the World. Joe also didn’t like the idea, but he did see an opportunity. There was a story that he and John wanted to do, but they hadn’t been able to figure out how. Now they did. So when Nellie returned to see if her pitch had been accepted, John had a counter-proposal. How would she like to go into a lunatic asylum for them?

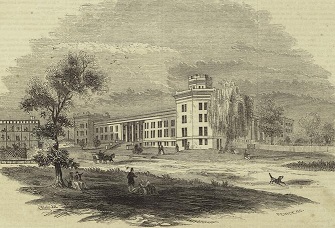

John and Joe had received multiple tips that the women’s asylum on Blackwell’s Island was mistreating its inmates, and that many who were sent there were not “insane” but merely being got out of the way for one reason or another. Fifteen years earlier New York journalist Julius Chambers had made history when he had gotten himself committed to Bloomingdale Insane Asylum in order to expose the abuse going on there. Now Joe wanted Nellie to do the same. [1] It was a dangerous assignment, in more ways than one. But Nellie was up to the challenge. She spent that evening at home practicing in front of a mirror, and stayed up all night in order to lend her performance some verisimilitude. The next day she dressed in a cheap gray dress and checked into a cheap boardinghouse, under the name of “Nellie Brown”. That evening she sat in the parlour, occasionally telling other guests that they “looked crazy”, before causing a scene when she refused to go to her room and tried to sleep in the stairwell. She stayed awake for the second night running, and then the next morning caused a new scene by refusing to leave her room and insisting that somebody had stolen her luggage during the night. (Of course, she hadn’t checked in with any luggage.) Eventually the boarding house owner called in the police and she was taken down to the station.

The police took Nellie to a judge to decide what to do with her, and Nellie gave an admirably incoherent performance. Her basic story was that she was from Cuba, that she had a headache, and that she couldn’t remember anything. To his credit the judge came to the conclusion that she had been drugged (which was not far from the truth) and had her sent to Bellevue Hospital. He also asked the reporters in the court to try to find out who she was, and both the New York Sun and New York Times ran articles about her. At Bellevue, the doctors were united in their “professional” opinions. One declared her “positively demented”, while the head of the “insane pavilion” said that she was “positively demented”. That vague and unscientific diagnosis was enough to condemn her, so on the 25th September 1887 “Nellie Brown” was committed to the Blackwell’s Island Lunatic Asylum.

Of course Nellie was unable to keep written notes, so she was forced to rely on her (luckily excellent) memory. She began by surveying her fellow patients, and soon realised that many of them seemed to simply be unable to speak any English, rather than suffering any mental illness. On her arrival she was given a meal of “five prunes, stale bread and pink coloured tea”. She was unable to stomach any of it before she was taken off, forcibly stripped, given an ice-cold bath and then locked in a tiny room. She was given no opportunity to dry herself, and was forced to sleep with wet hair and in wet clothes. Despite her fatigue, sleep was difficult as she realised that if there were a fire she would have no means of escape, between the locked door and the bars on the windows. It was a bad beginning to a terrible ten days.

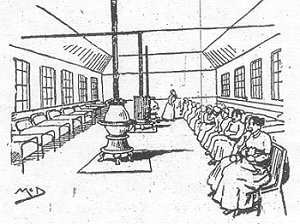

Nellie soon found out that life at Blackwell’s Island was one of dreary routine. After an inedible breakfast, the patients spent the morning in maintenance of the hospital; cleaning and doing laundry. Once that was done they were herded onto hard wooden benches and left to sit there in silence for the rest of the day. Unruliness or disobedience were swiftly punished, usually with force. As Nellie later observed, it was a routine that would eventually have destroyed the mind of even the sanest woman. Luckily for her, she knew that her time there was limited. A lawyer named Peter Hendricks arrived to free her on the 4th October. Nellie felt bad leaving behind the women that she had befriended there, but she hoped that her articles might help to free them too, or to make their lives more tolerable at least. Blackwell’s Island had no idea of the light that Nellie Bly was about to shine on them.

Nellie’s first article about her time in Blackwell’s Island was published on the 9th October, five days after she left. It was called Behind Asylum Bars, and it was an immediate media sensation. Papers all across the country syndicated it, and it was the talk of the entire country. She followed a week later with Inside the Madhouse, which was equally popular. As a result of all this publicity, New York Assistant DA Vernon Davis set up a grand jury investigation into the asylum. Nellie was called to give evidence at it. As well as leading to the release of many of the woman held in the asylum despite not being ill, this also led to an $850,000 increase in the budget for the management of mental hospitals and a huge increase in the rigor required by their examinations.

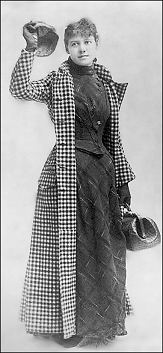

After her success, Nellie was not put back onto “women’s subjects”. Instead she got to write articles about mistreatment in prisons, political corruption and (showing the great regard she was held in) even women’s suffrage, which few other papers dared to write positively about. In 1888 she came up with a new adventure for her to write about. It was the 15th anniversary of the publication of 80 Days Around The World, the novel by Jules Verne. Nellie sat down with a set of timetables, and figured out that she could make the journey in 75 days. Why shouldn’t she make fiction into fact and set out to see if she could beat Phineas Fogg’s time? John Cockerill was willing to give it a go, but the other editors were more dubious. One said that he didn’t want to send a woman into such peril, and they should send a male reporter instead. Nellie told him that if they tried, she’d get another newspaper to send her and she’d beat him. Eventually, she persuaded them to relent. In November of 1889, a year after she had made the proposal and amid a storm of publicity, she set out.

Nellie was unaware when she began her journey that she was actually in a race. Cosmopolitan magazine, hoping to ride the wave of publicity, recruited fellow female reporter Elizabeth Bisland to set off in the opposite direction on the same day. Elizabeth had only six hours to prepare for her trip, as it was a last minute decision. Nellie had slightly longer. She pared her traveling kit down to the essentials, and had a hard-wearing dress specially made for her to wear for the whole trip. Her single suitcase held some changes of underwear, toiletries, writing tools and a few traveling essentials. With this light burden she boarded the German ship Augusta Victoria, the first of the luxury Atlantic liners. It was Nellie’s first sea voyage, and predictably she immediately became horribly seasick.

It wasn’t the best of omens for her trip, but after 22 hours in bed Nellie arose a new woman. The captain was relieved, as he’d been afraid that she had died in her cabin. During the rest of the trip she got to know the other passengers. They included an American girl who seemed to know everything about everything, a man who took his pulse after every meal and noted it down, and an old lady who refused to undress when she went to bed for fear that she’d be found in a disreputable state if there was a shipwreck. Despite the bad start, when the ship arrived in Southampton Nellie was almost sorry to say goodbye to it. But the road beckoned.

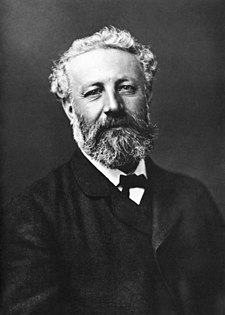

From London Nellie set sail to Paris, where she had to interrupt her schedule for a pilgrimage out to Amiens. Jules Verne himself had naturally heard of her journey and wanted to meet this American girl who wanted to beat his hero Phineas Fogg. They did not speak each other’s language, but with the aid of a translator they had a lively discussion. One interesting coincidence was that his book had been inspired by a newspaper article he read, and now a journalist had been inspired by him. Verne had conducted his journey entirely on paper, but he was still willing to offer advice on her rough itinerary. He was reportedly disappointed that she wasn’t planning to stop in India, though he himself had admitted within 80 Days that it was an unnecessary diversion. As the pair parted, Verne promised to cheer for her if she beat Fogg’s fictional time.

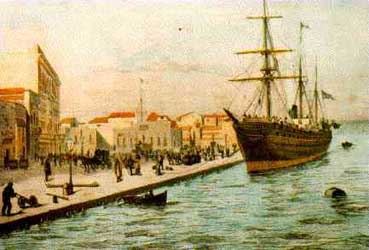

Nellie headed back to the coast and boarded a ship at Calais that would take her through the straits of Gibraltar and across the Mediterranean to Italy. These hops on board ships were the core of her journey, as the advent of the train on land had been met by powered travel in metal boats at sea. Sea travel remained the fastest form of travel when available, at least until air travel came along and upset the applecart. Back then the world was much less joined up – as Nellie found out when she left her ship in Brindisi in southern Italy. She asked to send a telegraph to New York to update her editor, and was shocked when the telegraph operator asked her what country New York was in.

Those updates came a little less frequently than the World would have liked, and definitely didn’t carry the detail they wanted. Nellie sent her written notes back by ship, so as she traveled further they took longer and longer to get back. What traveled faster were the articles written about Nellie by the newspapers in the countries she arrived in. News traveled on the telegraph wire, and the papers could afford to send more details than Nellie did. Elizabeth Bisland’s articles were also published, though since Cosmopolitan published monthly they didn’t need the constant feed that the World did. It’s interesting how the two writers matched their schedule: Nellie wrote immediately and excitingly about her impressions and the active world around her; while Elizabeth wrote more languidly and lyrically, dwelling on details like the colour of the Pacific ocean.

From Italy Nellie headed south, towards the Suez canal that cut through Egypt. She was not sick on this trip, but she did encounter something nauseating. One of her fellow passengers decided that this woman traveling alone clearly wanted nothing more than his attention, and was soon declaring his love and proposing marriage. His attentions had been prompted by a rumour on the ship that she was “an eccentric American heiress”, as the story of her trip wasn’t quite as well known in this part of the world. The man grew more and more insistent over the voyage, so it was a great relief to Nellie when he fell ill with seasickness.

From Egypt and through the Suez to Yemen, Nellie began hopping along the southern coast of Asia. Her next stop was Sri Lanka (which was called “Ceylon” at the time), and from there she travelled to Singapore. In Singapore she bought a pet monkey, and then headed to Hong Kong. She arrived on Christmas Day, 41 days after her departure. This was when she found out that she had a rival, as the clerk told her that Elizabeth Bisland had passed through three days earlier. Nellie declared her disinterest in racing, and said that her only goal was to make her seventy-five day target. From Hong Kong she headed to Japan (where she made sure to write about the fashions that were intriguing America at the time), where she boarded a steamer heading across the Pacific. It was a two week journey, and all she could do was sit and wait it out.

Rough weather in the Pacific meant that it took sixteen days for Nellie to make it to San Francisco, putting her dangerously behind schedule. Luckily her journey was such big news in America that the World had chartered a train specifically to get her back to New York. The train had only one car, in order to ensure it could make the best possible speed. Along the route there were brief stops to greet cheering crowds, and the train carriage soon began to fill up with flowers and fruit baskets. Finally she stepped off the train in Jersey City, where she had begun her journey. A vast crowd cheered as she threw her cap in the air. She had made her trip in 72 days, beating her own target by three days and Elizabeth Bisland by four. And she was home.

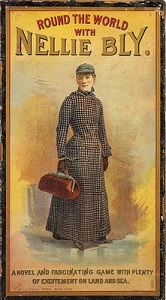

Nellie embraced her new celebrity role, which included her third book (Around The World In 72 Days), a lecture tour and even a board game. Her record was broken within a few months, but nobody really cared. (Nobody paid much attention to Elizabeth Bisland either, which suited her just fine. Her articles for Cosmopolitan about the trip were also collected into a book. She went on to become an editor there, as well as writing several more books.) Nellie took full advantage of her new celebrity status in order to write whatever she wanted, covering progressive issues. Then in 1895 Nellie Bly herself became news once more, when the society pages announced her engagement to millionaire industrialist Robert Seaman.

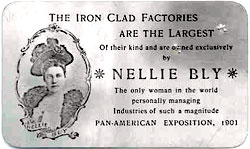

It was a whirlwind romance, with the pair marrying within a month of their first meeting. Robert Livingston Seaman was over forty years older than Nellie, and as could be expected there were rumours that she was marrying him solely for his fortune. Robert himself seems to have worried about this, as he hired somebody to follow Nellie at one point. It was a rough time, and Nellie escaped into her writing. She wrote several articles during this time, including an interview with the famous American suffragist Susan B Anthony. She also wrote several articles that included some “advice to bad husbands”. This airing of dirty laundry seems to have done the trick, as Robert apologised and took her with him on an extended trip to Europe. From 1896 to 1899 the pair spent time living in most of the capitals of Europe, before returning to America where Nellie became the president and the public face of Iron Clad.

In 1901 the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company exhibited at the Pan-American Exposition. Metal cards featuring Nellie’s face and the company’s information were handed out to attendees. In part this focus on her work may have been because Nellie’s little sister Catherine passed away around this time. A new tragedy struck in 1904 when Robert was hit by a wagon while crossing the street. He died from complications due to his injuries a month later. As a result Nellie became sole owner of Iron Clad, and it was during this period that the company’s two most famous innovations came about. The first was employee benefits, including medical care and pensions. The second was a design inspired by one of Nellie’s research trips to Europe and perfected by her employee; genius engineer Henry Wehrhahn. This was a design of steel barrel featuring flanges at either end to allow for guided rolling – the same style of metal drum that is now standard across the United States.

It’s a popular myth that it was Nellie’s employee benefits that led to Iron Clad running into financial difficulties. In fact it was down to widespread embezzlement in the company’s financial department, abetted by a supervisor there who was himself embezzling. Nellie found out about the fraud in 1909, and by 1911 she was forced to begin fighting off bankruptcy proceedings. She was able to avoid these, but wound up with a warrant for “obstruction of justice”. To avoid facing these charges, and to seek out new financial backers, Nellie set off for Austria in the summer of 1914. She intended to stay a few weeks. She would be there for five years.

When World War I broke out, Nellie found herself on the front lines of the biggest story in a century. Naturally she wanted in. She cabled the New York Evening Journal, a rival to the World where the editor was an old friend. The “Journal” was a Hearst paper, and William Randolph Hearst (link!) always loved a good war. Nellie became their official correspondent in Austria, and became best known for her reporting of conditions on their Eastern Front with Russia. She lived with a friend named Oscar Bondy, an industrialist who owned several sugar factories. America’s entry into the war made things a bit more awkward for her, but at the end of the war she moved to Paris. In January of 1919 she finally got the papers to return home to America.

Nellie returned to tragedy and confusion. Her mother Mary, who had been holding her property in trust during her absence, had died during her absence. Mary’s will had left everything to Nellie’s elder brother Albert, and he had taken that to mean literally everything – including Nellie’s savings and control of her company. Nellie was forced to take him to court to win back her money. Luckily she was able to get a job as a columnist at the Journal, where she interviewed the anarchist Emma Goldman and became involved in various efforts to help single mothers and orphans.

Nellie eventually regained control over her money, but she didn’t have long to enjoy it. In January of 1922 she died of pneumonia, aged 57. She left her Austrian assets to Oscar Bondy. Her brother and she may have made peace, as she left him a share of her estate, and the rest to her niece Beatrice. Beatrice was charged to look after several orphans who Nellie had been supporting, including a half-Japanese boy who Nellie recognised as her ward and left some money to in her will. She was remembered in her obituaries for her many feats of journalism, and one described her as “the best reporter in America”. She’s regarded as a pioneer to this day, with an award in her name given annually by the New York Press Club. Fittingly, it’s given out to reporters with “three or less years professional experience” – a nice touch for the “Lonely Orphan Girl” who wrote from her heart, and who made the world listen.

Images via wikimedia commons except where stated.

[1] This was the first time she altered the spelling of her surname to the more distinguished-looking “Cochrane”.

[2] Perhaps showing that imitation actually is the sincerest form of flattery, in 1889 Julius Chambers would replace John Cockerill as the editor of the World.