Missing Beats | Women in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road

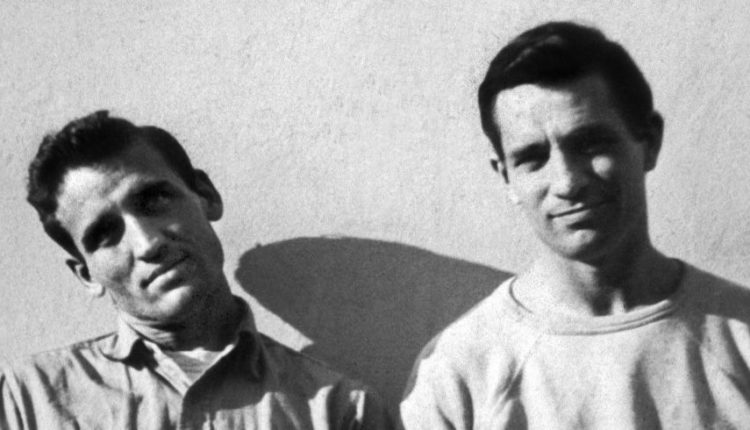

I first met On the Road when I was twenty years old. It was unlike anything I had read before. The intensity, hedonism, friendships, freedom and rebellion resonated deeply. I loved how the sentences pulsed and flowed with an audacious energy. Kerouac’s prose was music. I was fresh out of 19th Century Lit classes and this book, by comparison felt very contemporary. I fell in love with it on first read, bouncing about on a Bus Éireann boneshaker from Waterford to Cork. Later I fell in love with the legend of the book: the autobiographical elements – I poured over biographies matching characters up with their real-life counterparts; the legendary scroll bashed out in a 3-week Benzedrine-fuelled stint of manic artistry; the stories of the lives and works it inspired. I related to Sal and Dean’s constant hunt for the heart of Saturday night – but there were no strong female characters to identify with.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”#3535DB” class=”” size=”17"]Kerouac’s male characters were looking to flee the mindless consumerism and claustrophobic conformity of suburbia that was dominating America.[/[/perfectpullquote]p>

Often hailed as a counter-culture classic for its attitudes towards conformity, consumerism, race, sexuality and drugs, and yes in many ways On the Road was revolutionary. But there is an alternative way to read this book, because despite its reputation as a treatise of rebellion, it is in many ways a conventional novel rooted in the American literary tradition. A further element of the novel that problematises reading it as a departure from the mainstream is Keroauc’s disappointing marginalisation of women and his perpetuation of the patriarchal attitudes that dominated the post-war period. In that sense, it is very much a book of its time.

Kerouac’s men bond over their shared love of bop jazz music, adventure on the road and smoking weed. The influence of Kerouac’s American literary forefathers is there throughout the book. Many iconic works of American literature depicted by the flight of male protagonists from civilisation, women and responsibility to the freedom of nature or the wilderness and exclusive male company. Melville’s Ishmael went to sea aboard the all-male ship the Pequod, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn floated down the Mississippi River on a raft with the male slave Jim, while Kerouac’s pals, Dean and Sal, escaped to the endless possibility of the open road, just as Walt Whitman had done in the 1850s. The main elements for a good old fashioned American tale of male adventure are clearly: travel, nature and a male companion.

In ways, it is not that surprising that Kerouac’s novel, set in the late 1940s retells the archetypal American tale of male escape. Kerouac’s male characters were looking to flee the mindless consumerism and claustrophobic conformity of suburbia that was dominating America. Suburban living represented everything from which Dean and Sal were trying to get away from. Kerouac was critical of the prevailing conformity, he wrote “This is the story of America. Everybody’s doing what they think they’re supposed to do”. Paradoxically by denouncing conformity, Kerouac was conforming to the American literary tradition of Emerson and the Transcendentalist writers who advocated nonconformity and rejected materialism long before the Beat writers. Emerson wrote his treatise on nonconformity Self-Reliance in 1841. Henry David Thoreau built a wooden cabin at Walden Pond to escape the materialism of an increasingly industrialised America. F. Scott Fitzgerald also expressed his discontent with the consumerism of 1920s America in The Great Gatsby. Denouncing materialism and criticising conformity were nothing new to American Literature.

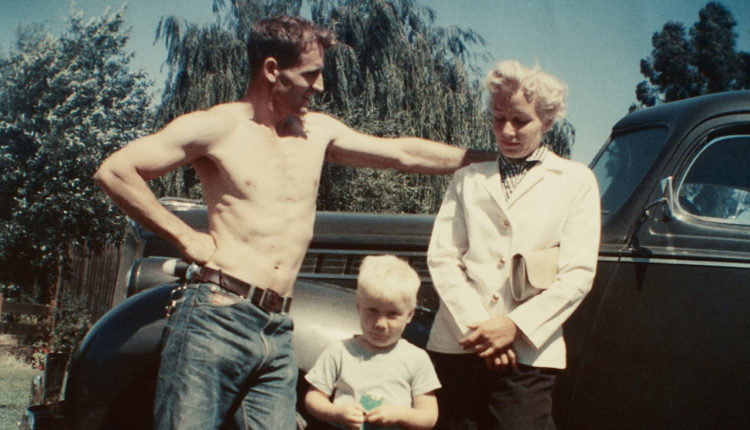

Since it was first uttered Beat became synonymous with rebellion. The Beat writers were viewed as a subversive literary movement, committed to ending all forms of coercion and oppression but their revolutionary attitudes did not extend to their depiction of women. Kerouac fails in On the Road to develop his female characters – they exist as mere accessories or possessions to the important male characters. Their role, merely functional is to provide men with sexual pleasure and perform their domestic duties. They are portrayed as nurturing, maternal and caring, willingly confined to their domestic roles. The feminine ideal is outlined as silent, passive and submissive to male authority. Kerouac creates female characters that fit unambiguously into neat categories: virgins, whores, wives, mothers, sex objects and domestic slaves.

Camille is archetypically feminine – she is a sympathetic character. Her love for Dean is depicted as unconditional. She writes him a letter overflowing with affection and understanding, even after he abandons her and their children. Similarly, Jane Lee is also portrayed as an attentive wife who submits to her husband’s dominance. Kerouac repeatedly portrays women as stereotypically fragile, passive and weak. Sal’s temporary girlfriend Terry is depicted as a defenceless, submissive type. She is portrayed as the epitome of the good, nurturing housewife caring for her ‘husband’ Sal the breadwinner.

Marylou is depicted as vindictive and unintelligent. She is repeatedly called a whore by both Dean and Sal, presumably she is condemned and labelled a whore because she sleeps around, unlike Dean whose sexual promiscuity is considered an expression of his masculinity and something to be celebrated throughout the novel. Lee Ann defies the expectation that she should be silent and submissive, and is punished for her rebelliousness. Sal refers to her as “that untamed shrew”. She is portrayed as shallow and materialistic, her only ambition to marry for money. Dean’s abuse of women sometimes manifests itself as physical violence, Sal mentions in a worryingly blasé manner that Marylou was black and blue from a fight with Dean. Through his uncritical portrayal of Dean’s abuse of women Kerouac condones the mistreatment of women. Marylou and Lee Ann are condemned for their defiant strength and independence. Kerouac’s construction of their characters as unsympathetic illustrates everything a wife or woman should not be, by the era’s patriarchal standards.

This is the first part of a two part article. Read part two here.