The Broken Men of First Man and A Star Is Born

A couple of years ago when I was still a fresh-faced college student a friend of mine asked me who my favourite actresses were. I found myself surprisingly stumped by the question. There was no shortage of great actresses I could point to (Meryl freaking Streep comes to mind) but I didn’t have any kind of deep familiarity with their work the way I had with several male stars of past and (then) present.

I was actively embarrassed at my lack of a satisfactory answer at the time, deeply aware of how truly ignorant it made me look. This was a moment of personal ignorance sure but it was also one indicative of the patriarchal structure of the film industry itself. I resent myself writing this for the sheer obviousness of it but the film industry is a male dominated world that, despite recent positive developments in recent years, remains frustratingly un-diverse (see Jason Blum’s recent comments if you need an illustration).

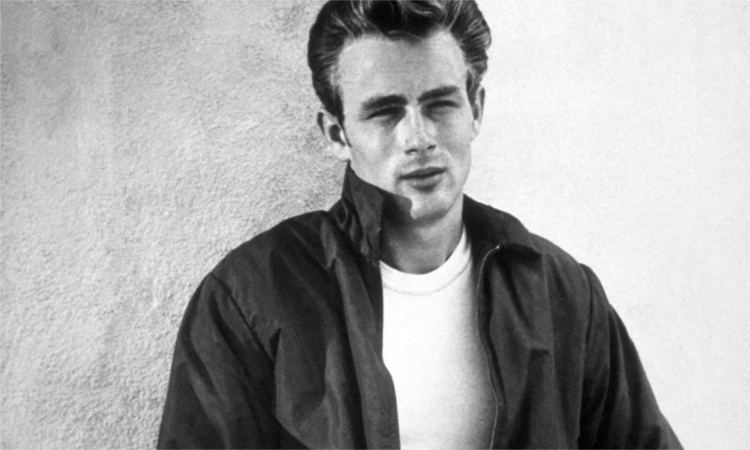

Hollywood, and the media landscape at large, is an industry that seeks to employ men to celebrate men above all others, lauding the likes of Marlon Brando and James Dean as revolutionary creative forces while rarely affording actresses the same mythology, the same enduring cultural potency. Masculinity is one of the great fixations of cinema, old and new, a fixation that has produced some of the most iconic imagery the movie business has ever offered up. Who I was in college was an ignorant person for sure. But my ignorance wasn’t entirely my own. It was inherited.

The images of modern masculinity have certainly evolved from the days of John Wayne. An increase in social consciousness has seen an attempt to adopt the masculine image for the modern day, essentially a man of action unafraid of feeling and sensitivity. Both First Man and A Star Is Born recycle these images of a bygone era of masculinity but for much different purposes.

Both are largely films about men who struggle to live in the world but what this struggle is used to exactly illustrate about toxic masculinity cannot be more different. Plot-wise there are few similarities between First Man and A Star Is Born. First Man, Damien Chazelle’s follow-up to the much praised and ridiculed La La Land, documents the tumultuous events leading up the Apollo 11 mission to Mars, specifically focusing on the tragedy rich path of Neil Armstrong.

A Star Is Born, the debut directional film of actor Bradley Cooper, largely tells the story of an ageing musician whose downward trajectory is contrasted with the success of his musical protege and romantic partner Abby (Lady Gaga). These two films will never make a great double feature. They stand utterly apart. Yet the men who stand in the middle of these productions together say a lot about how we approach masculinity in 2018.

I don’t know what the film Drive means to you. I know what it means for many men my age who were young enough when it came out that a movie could still entirely reinvent their taste and consciousness. Drive was a movie you had to see and you had to like it, there were no other options. It was no blockbuster but everyone I knew had seen it and having seen it meant something, like you belonged to a cult whose values were unspoken and yet known.

Much of what makes Drive work is Nicolas Winding Refn’s masterful direction for sure but truly central to its appeal to young men was Ryan Gosling in the central role, a role that is by no means the biggest in his career but is the role biggest to his career so far. It reinvented him from indie darling to true ‘coolest man alive’ status, shaping a persona that he has stuck with today (a silent man masking hidden layers of violence and honour). I remember modelling myself on his character from the movie and it was painfully clear that people around me were doing the same. It’s foolish but it’s exciting, rooted in a time of adolescence were movies can really mean something to you that your jaded adult self won’t ever allow.

Gosling in these movies was a guy who could easily kick your teeth down your throat but this explosive capacity for violence was paired with a real sensitivity, a beating romantic heart buried under layers and layers of muscle. This onscreen persona was softened further by Gosling’s offscreen persona, a movie star with old school looks and acting chops but bolstered by a truly modern fashion taste and offbeat charisma that made him a pinup for men and women alike. He was the Hollywood hunk for a feminist age, a six foot plus tall walking meme. While the mantle of a modern movie star has perhaps moved on from Gosling to a younger generation of indie darlings and scum-bros he remains in many ways the OG guide on how to be an adored straight white dude in a time where straight white dudes’ stock is hanging dangerously low.

Gosling’s performance in First Man is in many ways typical of his post-Drive career though it does minimise his movie star charisma. Here he plays Neil Armstrong, a man of unparalleled toughness whose inability to communicate hides his deep reserves of pain and grief. Chazelle frames the Apollo 11 mission to the moon in First Man as the ultimate expression of a man whose discomfort with his own feelings drives him to greater and greater extremes of self-isolation.

Armstrong, the movie argues, is a man that is somehow more comfortable in a tin can in space in life or death scenarios than he is at family gatherings, much to the frustration of his wife played by Claire Foy. These scenes of impossibly fraught space travel are undeniably brilliant feats of filmmaking that effectively capture just how rink a dink these early steps into space exploration were and are arguably worth the price of a cinema ticket alone. The personal, family side of this story is not so brilliantly told.

Chazelle’s first two films, Whiplash and La La Land, cemented him as one of Hollywood’s most exciting directors, yet one who had difficultly telling a fully assured narrative. First Man continues the thread. While the character of Armstrong’s wife is not quite as thinly drawn as that of other countless ‘wife’ characters in Hollywood movies, there is not much for an actress of Claire Foy’s skill to really hang her hat on which is enough to ultimately derail the movie entirely. There’s such an emphasis in First Man on the physical and mental challenges that space travel presents that Armstrong’s growing distancing from his family fails to really register in any meaningful way. In fact, making the case that Armstrong’s emotional coldness was what made him capable of such incredible feats of cool headed survivalism acts an an unintended glorification of the emotionally angst ridden stoicism that the film hopes to redeem Armstrong of.

Perhaps First Man was destined for controversy in such divisive times. It certainly fell straight into it. Once the film debuted at the Telluride film festival a conservative bubble of indignant disbelief arose over the lack of a shot of Armstrong or Buzz Aldrin planting the American flag on the moon’s surface. The idea that this makes First Man an unpatriotic movie is an absurd one but it is not a completely mindless form of patriotism. What First Man seems to mostly mourn is the notion of a past America that one could be proud of, a potentially interesting idea that also probably doesn’t hold up under any kind of scrutiny at all. One of the film’s great failings is how it fails to really capture the extent of social upheaval and unrest that defined the era of the Moon landing, a time not completely unlike our present moment. The fact that the extent of the space programme was pretty heavily opposed by a majority of Americans is acknowledged but only perfunctorily (Gil Scott Heron’s “Whitey On The Moon” is used to do most of the explaining here).

In the end what we get with Chazelle’s film is a weirdly nostalgic movie yet it is not a nostalgia for a certain period of time but more a period of being. First Man is all about the man, plain and simple. There is little room for or interest in anything else. It is about men, white men, accomplishing things under great stress, alone and independent. Armstrong is an emotionally crippled character played by an actor whose innate charisma and good looks have served to romanticise emotionally crippled characters for years. First Man’s fundamental flaw is how completely it identifies with the perspective of a protagonist, resulting in yet another movie in which the solitary experience of a man takes emphasis above everything. It aims for sublime and ends up with fine. Watching it is like déjá vu: You’ve seen this story before.

Now A Star Is Born is quite literally a story you’ve possibly seen before. The Bradley Cooper directed, Lady Gaga starring A Star Is Born is the fourth remake of the original and has been met with so much critical acclaim and public attention that it is now perhaps already the definitive version of this story. Cooper plays Jackson Maine, the tinnitus afflicted, hard-drinking country rock star who is reinvigorated when he discovers Ally, an incredibly gifted yet insecure woman who has appeared to have given up on her dream of making it as a musician.

If this synopsis reads as a narrative that is potentially condescendingly paternalistic that is because it does read that way. How else to interpret a film whose narrative largely centres around an older man who makes the success of a younger woman possible through his clout and attention? But to see A Star Is Born in such terms is a disservice to the movie. There are certainly old-fashioned elements and tropes at play here but Cooper does a fine job of skirting around such sensitive material and finding something purer and much more resonant in his telling of the movie. His A Star Is Born is a much more modern piece, even though the film is at its best when it feels utterly timeless.

Much of the pre-release conversation around A Star Is Born propagated the idea that the film would be about an increasingly irrelevant star who struggles to accept the meteoric rise of his romantic partner. To a certain extent this synopsis is not entirely false but it is maybe inaccurate. Jackson doesn’t resent Ally so much for her fame but more so for the effects of fame, both on her and himself. If Cooper’s film is making any kind of point it is the sanctity of having something meaningful to say and being true to your unique self. Ally doesn’t completely sacrifice her authenticity in order to succeed but enough that it does drive the alcoholic Maine back to drinking (yes, this plot development is absurdly melodramatic).

Ultimately, and thankfully, Maine’s true despair doesn’t stem from resentment of a younger woman’s success but from his own distorted relationship with self. Maine values authenticity above all else but his own fame and success has transformed him into a walking caricature, a figure of myth who is incapable of engaging the world in any real way.

One of the great virtues of A Star Is Born is how it subverts our expectations of the central character. The tortured, alcoholic artist is well worn material but Cooper manages quite well to a put a more modern spin on the trope, crafting a sweet, non-violent character who is as comfortable backstage at a drag bar as he is in some dive bar. And while he certainly facilitates Ally’s success he never takes credit for it, nor does he regard his own career as taking precedence over hers.

This is a tortured male protagonist but his demons are never treated as anything virtuous as they arguably are in First Man. Maine is simply flawed and not in any kind of romantic way. He might be an updated spin on an outdated character but he is still an outdated character, one who is self-aware about his lack of a place in the modern world. First Man aims to resurrect the classic male stereotype while A Star Is Born aims to bury it. The latter succeeds, the former doesn’t.