Out of the Armchairs, Into the Seas

Next time you visit that fine institution that never succumbed to the vagaries of fashion: the Natural History Museum on Dublin’s Merrion Square take a look at the display cabinets that contain the marine exhibits.

Loiter around these glass cabinets and read the old labels of Victorian typescript on phials and bottles containing the pickled remains of sea creatures. You will notice that many of them are dated from the 1880’s.

Consider now those learned and wealthy gentlemen of leisure whose scientific curiosity and doubtless, sense of adventure, led them out onto the rugged, grey seas around Ireland to find curiosities and suitable specimens to fill the Museum’s display cabinets. Rather than waste their time, wealth and education on raffish pursuits they chose to spend them on more erudite ones that would add to our store of knowledge. In this instance that would entail a spot of deep sea dredging off the Irish coast in the hope of harvesting some spiffing specimens as yet unseen by human eyes.

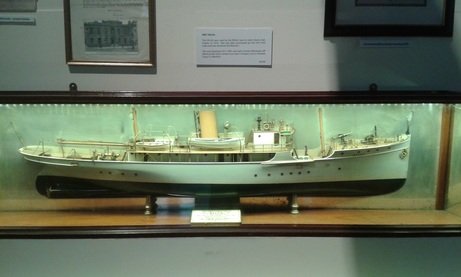

In 1881 the Royal Irish Academy gave a grant to British zoologist, Alfred Cort Haddon to investigate the marine fauna of Dublin Bay. Many new specimens were found while dredging and shore collecting at Dalkey Island, Dalkey Sound, Kingstown, Dun Laoghaire, Malahide, Monkstown and Bray. These were then preserved and presented to the Natural History Museum where they can be viewed today. Indeed, there is a magnificent example of a working dredging machine on display in the National Maritime Museum in Dun Laoghaire dating from 1906.

The impetus for the 1880’s dredging cruises around Ireland was doubtless the British Challenger expedition, which took place between 1872 and 1876. The Challenger cruise introduced scientific oceanography to the world at large, and its success was not lost on Haddon and his contemporaries. The three-masted, square-rigged, wooden HMS Challenger sailed 68,890 nautical miles across the oceans of the world, even going north of the limits of drift ice in the North Atlantic polar seas and south of the Antarctic Circle, collecting masses of new material for the British Museum. A veritable steam punk paradise, fifteen of the ship’s seventeen guns had been removed to make way for purpose-built scientific laboratories and workrooms. [pullquote]Green had been advised to spend the winter in a milder climate due to ill health. With the pluckiness of Captain Marryat’s Masterman Ready his response to rest and recuperation was to go to New Zealand and be the first to conquer Mount Cook.[/pullquote]

Haddon, incidentally, was also fondly referred to as, ‘Haddon the Head-hunter’, being regarded as one of the founders of modern British anthropology, since it was largely through his work that the subject assumed its place among the observational sciences. In his capacity as Assistant Naturalist to the Science and Art Museum of Dublin, he visited the Torres Strait islands north of Queensland in 1888 and 1889 to investigate marine biology, but while there he became equally fascinated by the customs of the native islanders. He returned ten years later with the Cambridge Torres Strait Expedition and recorded a number of dance and fire-making films on the Murray Islands, which incredibly still exist in good condition.

In 1885 Haddon welcomed the services of another stalwart, the Reverend William Spotswood Green, grateful for his unbounded enthusiasm in dredging operations. In 1881, Green had been advised to spend the winter in a milder climate due to ill health. With the pluckiness of Captain Marryat’s Masterman Ready his response to rest and recuperation was to go to New Zealand and be the first to conquer Mount Cook. So much for rest then.

Sea dredging apart, in 1888 the hyperactive Green would also set sail for Canada to study the Selkirk Glaciers in the Rocky Mountains before completing a field trip on behalf of the Royal Dublin Society to study North American fishing ports. He was eventually appointed the first Chief Inspector of Fisheries, and under his supervision, the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction bought the steamship Helga (the very one that would lob 18-pound shells on the GPO and Liberty Hall in the 1916 Easter Rising) to research and patrol Ireland’s fishing grounds. But for now, the scene was set to explore the South West Coast of Ireland; the purpose being to investigate the fauna between the coastline and the 1,000 fathom line. With the newfound realisation that life could indeed be sustained at depth, these exploratory fishing cruises would fill a major gap in contemporary knowledge.

In comparison with their global expeditions, Alfred Court Haddon and Reverend William Spotswood Green were not facing a trivial task when they embarked on their first exploratory dredging cruise in 1885, and they weren’t long about rolling up their sleeves either. The ‘Lord Bandon’ left Queenstown at 3.30 pm on Monday, August 3rd, and dredging started at 5 o’clock the next morning, forty-nine miles west of Cape Clear, in ninety fathoms. “A most important consideration”, writes Green, “in a dredging expedition off the SW corner of Ireland, where the sea is nearly always rough, is to secure the co-operation of helpers possessed of sufficient zeal in the work to make them ignore the discomfort, and who may be proof against the mal de mer.”

Haddon’s narrative of the second cruise in 1886 reads like an archetypal Victorian explorer’s journal, with typical Victorian attention to detail.

“As soon as the garments of civilization were cast aside for those of a more nautical cut, the serious operations of putting the finishing touches to the derrick and sounding machine commenced. All the trawls and other tackle were overhauled, and the fluids and apparatus for the conservation and storage of specimens put in order.”

Refined and courteous on land, valiant and daring at sea, it is fair to say that these Victorian gents were not afraid of getting the job done in the face of adversity and it would be a thorough job. Haddon continues,

“All day the wind had been rising, the sky was overcast, and the sea was becoming more and more agitated. By 3.30 p.m. the weather was so ‘dirty’ that it was decided to put on ‘full steam’, and, if possible to make Valentia before nightfall. With oil-skins donned, all hands were busy stowing the gear, arranging the fishing-lines, sifting and washing the dredged-up sand, bagging the latter, and preserving specimens and writing their appropriate labels, ignoring the pitching of the steamer and the driving of the rain.”

Sadly, the deepest sea dredging on the 1886-87 cruises was a failure but faunal specimens were collected down to 594 meters. This included a sea anemone new to science, named Paraphellia greenii in honour of the doughty Green. There is no denying the stoicism of chaps like Haddon and Green in the face of adversity. Indeed, the cargo of intellect on these cruises was of the highest calibre; in the knightly realm, to be precise. Sir D’Arcy W. Thompson was a mathematical biologist whose work influenced that of Alan Turing, while Sir R. S. Ball was an astronomer who wrote The Story of the Heavens, a work which popularised the science of astronomy.

The final Royal Irish Academy sponsored exploratory cruise in 1888 again employed the Lord Bandon, but this time with the new name of Flying Falcon. Haddon looked after the animals and Green looked after the equipment and the oceanography. Robert Lloyd Praeger, ‘Irish Naturalist Optimist Omnium’ and author of The Way That I Went, describes a typical catch. “There were great sea-slugs, red, purple and green; beautiful corals, numerous sea-urchins with long slender spines, a great variety of starfishes of many shapes and of all colours, including one like a raw beefsteak, which belonged to a new genus; strange fishes and many other forms of life.” To get the cut of Praeger’s jib it is worth noting that the young Robert was so keen to get the skull of a dead dog that he borrowed his mother’s best saucepan in which to boil it.

Spotswood Green’s description of hauling up the trawl at Station 2 is telling.

“The trawl seemed very heavy, and as it approached the surface we could see it looming as a large white object in the clear blue depths. It was half full off Globigerina-ooze, so we had to let it wash about and drain for some time at the surface. By the time the animals were sorted from the ooze, with the help of the fire-hose, darkness had closed in, and a long and successful day’s work was concluded.”

James Thurber, American cartoonist and author, perhaps most famous for The Secret Life of Walter Mitty obliquely, and unintentionally, yet perfectly describes Globigerina-ooze through the eyes of one of his silently observing lemmings in The Shore and the Sea. “[T]he caves of ocean bear no gems, but only soggy glub and great gobs of mucky gump.” Serendipitous, and more colourful than the scientific explanation of the remains of dead animals and discarded shells piled up in thick layers on the ocean floor.

We owe a debt of gratitude to these gentlemen scholars who bravely scoured the rough seas around Ireland for our benefit and at no financial profit to themselves.

A version of this article was originally published on Berni Dwan’s blog, Old Filibuster, entitled ‘Gentlemen Dredgers’.