Ireland’s Woodstock: the anti-nuclear protests at Carnsore Point

A spectre hung over a Wexford beach – and all Irish society – in the 1970s: that of “Nuke Power”. In the ballad the House Down in Carne, this was described as “a terror” that promised to poison your children, and even strangle your poor dog, bringing decay and death. Also known as The Ballad of Nuke Power, the song about Carnsore Point was sung by Christy Moore at the Get to the Point festival in 1978, later called “Ireland’s Woodstock”. That was a culmination of anti-nuclear discontent encompassing all sections of Irish society. Environmentalism as we know it in Ireland owes its existence to the popular protest that occurred at that time.

Today there is political harmony with regard to the nuclear issue, with focus being primarily placed on safety. Colum Kenny of Dublin City University, and author of a book on the prospect of nuclear. observes that the Irish government says it “has firmly rejected nuclear energy”. This united view has not always been the case.

The appearance of environmental groups in this country correlated with industrialisation and the development of the Irish economy in the 1960s and 1970s, which many saw as having negative aspects. The growth of Irish environmentalism was enhanced by the island’s peripheral position but this did not lessen the movement following the stance of its counterparts on mainland Europe in relation to the nuclear issue and subsequently conservationism. Ireland was not just a follower but at the very forefront of environmentalism in Europe.

By the end of the 1960s, the Electricity Supply Board (ESB) started to explore the energy alternative of nuclear power. The linking of the electric grid with the ESB and the Northern Irish Electric Services (NIES) influenced the ESB. It tried the UK’s energy policy, which saw a nuclear power station at Windscale, since renamed Sellafield, Cumbria, from 1951. The pro-nuclear moves would receive Irish government endorsement in November 1973. This support was due in part to the disruption caused by the first oil crisis, which saw petrol prices rise by 30 per cent to 65p per gallon. Ireland’s dependence on oil was amplified by the rise in demand for electricity, with the state having one of the highest growth rates in Europe in relation to electricity consumption, averaging 10 percent over the previous ten years. Several locations were suggested for a proposal of the building of a nuclear power plant including Kilrush, County Clare, and Whiting Bay in County Waterford.

Yet the American physicist Edward Teller, “the father of the hydrogen bomb”, speaking at European Economic Community open hearings on nuclear power in January 1978, stated that Ireland’s energy output was “too small” to justify a nuclear reactor.

By September 1974 an application for planning permission by the ESB to build four energy stations at Carnsore Point had been lodged with Wexford County Council. However, the impact of the first oil crisis combined with the resultant recession and the development of a gas field in Kinsale lead to the nuclear option being put on hold.

The initial decision to use nuclear power to generate electricity was endorsed by all the political parties at the time, including the opposition, composed of Fine Gael and Labour. Likewise, the proposed development at Carnsore Point was welcomed locally in County Wexford.

A report prepared in the public interest sponsored by An Taisce, County Wexford, Junior Chamber of Commerce, Wexford and the South Eastern Scientific Council noted how the site at Carnsore Point met all the needs for the harnessing of nuclear energy. The many advantages for Wexford included job creation, the possibility of educational and training facilities in the area for technicians, tourism opportunities of tours of the station, with there being no apparent risk to farming in the county.

Hundreds under the anti-nuclear umbrella

In 1973 the formation of the Nuclear Safety Association and the development of Friends of the Earth branches saw more than 100 groups involved in the anti-nuclear campaign. The NSA was to grow into the Council for Nuclear Safety and Energy Resource Conservation (CONSERVE) in January 1975. Dr Robert Blackith of Trinity would add academic weight by being a proponent of the anti-nuclear position and the publication of The Power that Corrupts (1976) criticised the ESB’s approach with regard to its handling of information relevant to the public.

The anti-nuclear movement in Ireland opposed nuclear power not just for the safety dimension, but also the disposal of nuclear waste, uranium mining and the risk to Irish neutrality by pursuing such a policy. The opposition to nuclear power highlighted that the debate was not just about the energy option but also the ‘future of Irish society’. This position is illustrated in Matthew Hussey and Carole Craig’s Nuclear Ireland with ‘the question, then, of whether or not Ireland is to “go nuclear” is not just a technological one, but has a moral and economic base, about which it is the right of every citizen to decide.’

The start of 1978 saw Dail Eireann discuss the pursuit of nuclear energy. The Green Paper Energy Ireland outlined the desire of the government to have a combined coal-fired and nuclear-powered generated plant. Political scientist Richard Sinnott suggests that this “statement was probably the closest Ireland has come to having a nuclear power programme”. The Green Paper described Ireland as an “energy deficient” country, importing 80 percent of its energy requirements, 75 percent of which being oil which was “subject to unpredictable price rises and political embargoes”.

The Fianna Fail government led by Jack Lynch saw the proposal for Carnsore Point as part of their quest to “bring Irish industry into the future”. This was articulated by Des O’Malley, then Minister for Industry, who told a Limerick audience that “the consumption of electricity per head of population in any country is generally regarded as a sure pointer to the degree of development of that country”. Yet the sense of the government being out of step with developments in energy and the general public was displayed in the magazine Hot Press, which described the Green Paper as “diluted bullshit”. Other media suggested the emphasis should be on conserving energy.

The debate surrounding nuclear power in Ireland has been mirrored in Britain, France and Sweden, the latter of which had a general election in 1979 where the nuclear debate was central. When the anti-nuclear movement in Ireland called for a public inquiry, this was deemed not “helpful” by the then junior minister for the Department of Industry, Commerce and Energy, Ray Burke.

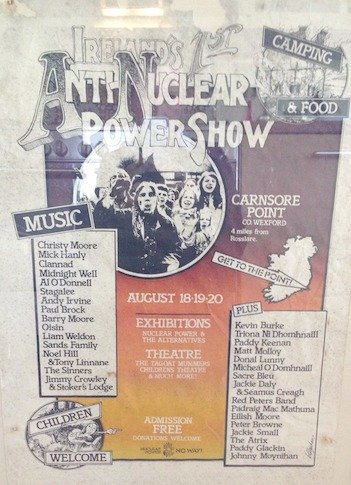

The creation of the Carnsore Collective led to seizure of the land for the proposed nuclear power plant for an anti-nuclear festival. Get to the Point would even try to arouse ‘the notoriously apathetic youth of the country’ (Ferriter). The festival included music from Christy Moore and Clannad, with speeches from figures such as German Green MP Petra Kelly and Dr Blackith. In the Irish Independent Liam Collins described the Carnsore Point festival as the “Irish Woodstock”. A success of the festival was its unifying effect, attracting young people of various interest groups from feminists to Marxists. It also portrayed the anti-nuclear movement as fun and on trend with its form of protest, compared to the mohair suits of Fianna Fail.

John Kelly of Fine Gael sought a public inquiry in the wake of the festival. Furthermore, Kelly criticised Des O’Malley’s “petulant behaviour towards the people who are specifically concerned about the proposed location… To tell them, as he did at his party’s Ard Fheis, that if Wexford did not want the station there were other places that did, is to treat them as though they were children refusing to eat rice pudding”.’ Pressure on government continued with public demonstrations in Cork and Dublin, the latter being the site of a ‘Monster Meeting’ in November 1978. In January 1979 The Late Late Show devoted a programme to the nuclear debate.

In addition, the reactor core meltdown at Three Mile Island in March 1979, plus the profile of the anti-nuclear movement led by consumer advocate Ralph Nader, the No Nukes concert featuring the first recorded live performance of Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, with Crosby Stills and Nash and Tom Petty cementing in ‘popular culture’ of the ‘nuclear industry…as the “bad guys” in this dispute’. A second festival at Carnsore Point entitled Return to the Point was more politically focused, but would not attain the same media coverage.

The government proposal was subsequently delayed as a response to the support for a public inquiry which Sinnott described as ‘The delay that this involved merged into a decision in favour of indefinite postponement. Postponement in turn merged into outright opposition.’ The role of Des O’Malley in the affair and his subsequent expulsion from Fianna Fail must also be considered. O’Malley was replaced by George Colley which ‘signalled a change in policy and a great weakening in the desire to build a nuclear power station.’ In fact, Colley would go on to state that he was not thoroughly convinced by the information on the safety of nuclear energy.

This clear reversal of policy was victory for all the endeavours of the anti-nuclear protesters at Carnsore Point and across the country. Even now, in December 2015, Energy Minister Alex White, speaking to news site TheJournal.ie, said: “I don’t see Ireland introducing nuclear, certainly not while I’m minister.”

From forming a coherent opposition to creating consensus about nuclear power – that is why Carnsore should be remembered.

Sources:

- Diarmaid Ferriter, Ambiguous Republic: Ireland in the 1970s (Profile Books, London, 2012).

- Colum Kenny, Fearing Sellafield (Gill and Macmillan, Dublin, 2003).

- Liam Leonard, Green Nations: The Irish Environmental Movement in Ireland (Springer, London, 2007).

- Perry Share and Hilary Tovey, A Sociology of Ireland (Gill and Macmillan, Dublin, 2007).

- Richard Sinnott, ‘Ireland and the Diplomacy of Nuclear Non-Proliferation: The Politics of Incrementalism’, Irish Studies in International Affairs, 6 (1995), pp. 59-78.

- Hilary Tovey, Environmentalism in Ireland: movement and activists (Institute of Public Administration, Dublin, 2007).