Andrew George Scott, ‘Captain Moonlite’

The jolly scofflaw is a common figure of admiration in society. The outlaws of Sherwood Forest, the highwaymen of Regency England, the outlaws of the Wild West, the “apaches” of the Parisien underworld, all enjoyed the glory of living outside society. Of course, said society enjoyed their tales all the more when they ended with the appropriate moral lesson, traditionally delivered at the end of a rope. Australia is not immune to the lure of the outlaw mystique, and songs and tales of the bushrangers who terrorized the isolated communities of the 19th century outback abound. Among them is Andrew George Scott, a man who began his life as the the son of a magistrate in County Down, but who ended it known to all by the moniker he had chosen for himself – the notorious Captain Moonlite. [1]

Andrew George Scott was born in Rathfriland, County Down, in 1842. His father Thomas was a Justice of the Peace who had once studied to be an Anglican clergyman, the height of respectability. Scott’s younger brother was content with this, but Scott sought something else. He ran away to sea, though he did not spend long at that, but instead studied engineering in London. After he gained his engineering degree he went to Italy for further studies and wound up fighting with Garibaldi’s Redshirts. In 1861 his father and mother emigrated to New Zealand, and their two sons came along. At the time the British government were offering substantial incentives to emigrants, and a young man with engineering qualifications would have received a handsome bonus. In the colonies he signed up to the armed constabulary and fought in the New Zealand Land Wars against the Maoris. He was shot in both legs and invalided out. While in hospital he was court-martialed for malingering, and given a dishonourable discharge. He admitted the charge, but claimed it was not cowardice that motivated him but rather distaste for the massacres of women and children perpetrated during the war. Indeed, once he was discharged from hospital he wound up travelling to the USA, where he joined the Union Army as a quartermaster. This job, as always, was a great opportunity for a man of unscrupulous morals, and he was said to have done very well out of it. In 1865 he left the army and moved to San Francisco, and two years later he moved to Sydney. [2]

In Sydney Scott made the acquaintance of Bishop George Perry, one of the most influential clergymen in Australia. [3] His early education in religion stood him in good stead, and Perry appointed him as a lay reader first in Bacchus Marsh, and then in the town of Egerton, near Ballarat. However his temperament was as ill-suited to the clerical life as it had been in his youth, and in May of 1869 he decided to abandon it in style; by robbing a local bank. To do this he masked himself and attacked the bank manager as he returned to the bank late at night. At gunpoint he first forced the manager, a man named Ludwig Bruun, to empty the gold from the safe (bought from local prospectors), and then to sign an affidavit where the robber absolved the manager of any responsibility, perhaps as a double-bluff method of casting suspicion on the manager. If so, then this was highly successful as though Bruun recognised Scott through the mask (reportedly thinking it was all some practical joke at first), Bruun was actually arrested for the crime himself as soon as he reported it, as was his friend and (the police believed) accomplice, James Simpson the local school teacher. It was in the note that Scott first adopted the aid of Captain Moonlite – the mis-spelling allegedly having been suggested to him by an English crook named Archie Telford who he met while he was in America as a method of leading the police astray. The logic was that the police would assume that it meant a less educated man had written it, as one would expect the highly educated Scott to know how to spell “Moonlight”. Bruun and Simpson were tried, but were acquitted for lack of evidence. Scott, who had testified against them, left Egerton.

Scott always claimed innocence in the Egerton Gold Robbery, though his later adoption of the Captain Moonlite moniker is almost as damning as the fact that he resurfaced in Sydney, financing himself through the sale of gold very similar to that stolen from the bank in Egerton. The money could not last forever, but when his account ran dry he simply continued to draw cheques on it. The last cheque he wrote purchased a yacht named the Why Not, on which he planned to make his escape (with, reports said, a young female “travelling companion”), but he had lingered too long. The water police arrested him as he left the harbour, and he was charged with fraud. He was sentenced to a year in jail, though he may have spent part of that in Parramatta Lunatic Asylum (whether through genuine or feigned distress is unknown). On his discharge from jail he was promptly re-arrested, as a detective named George Sly who had been hired by Bruun had tracked him down. He was sent to Ballarat, and while held there on remand he managed to escape from jail. He did this by cutting through the wall of his cell – a pointless gesture, it seemed, as that simply let him into another adjoining cell. However he was able to persuade the prisoner held there to join him in escaping, and the two overpowered the warden as he made his rounds. They let the other four prisoners in the jail out of their cells and then made a run for it. Scott was soon recaptured (though the fate of the other prisoners is unknown), and held more securely until he was put on trial. There he argued his own defence, and was by all accounts uncommonly persuasive. The evidence of the gold he had sold in Sydney proved damning, however, and he was sentenced to ten years hard labour, with one extra for his jailbreak.

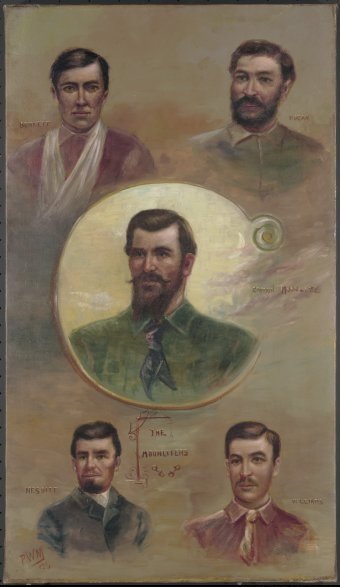

It was while he was in jail this time that Scott met James Nesbitt. The two became friends and, several modern scholars believe, something more. While it was never mentioned in the newspapers at the time, the letters the two exchanged (and a certain later incident) all point to a romantic relationship existing. But in the absence of solid evidence, all we can do is speculate. Scott was released in 1879 two years early for good behaviour, and Nesbitt was waiting for him on the outside. At first, he attempted to put his criminal career behind him, trading on the fame his jailbreak and robbery had gained him as a public speaker. Nesbitt became his assistant in this, and one person who met him at the time described him as “posing as a mixture of Dick Turpin and Napoleon”. Fame as a criminal was a double-edged sword however, and as Scott travelled around the territory he was hounded by both police and reporters trying to tie him to any local scandal or crime (for example, the robbing of the Lancefield bank). Eventually, perhaps inspired by the tales of the exploits of the Kelly Gang, Scott decided to live up to his legend. He used his fame as Captain Moonlite to recruit a gang of four impressionable young men, the oldest of whom was 21 years old, and the youngest only 15, and with them and Nesbitt he set out into the bush.

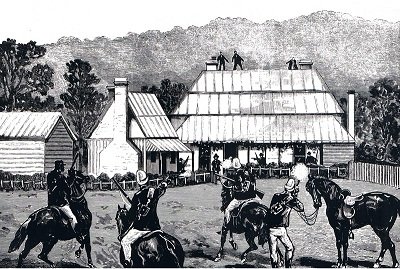

At first, they enjoyed a certain amount of success. They were operating in the same area as Ned Kelly’s gang was at the time, and the fearsome reputation of his band of hoodlums worked in Scott’s favour. People would hand over food and weapons, thinking that this gang was the same one. One police superintendent would later claim that Scott had applied to join Kelly’s gang, and Kelly had replied with a terse warning that if he saw Scott he would shoot him. Whether this is true or not, as the winter of 1879 approached the Moonlite gang headed north into New South Wales. There they hoped to outrun their reputation and find an honest berth to overwinter. Their destination was Wantabadgery Station, which had a reputation for offering a generous welcome to travellers. Unfortunately the owner responsible for that generosity, Walter Orton Windeyer, had unexpectedly died that spring. The new owner, a Scot named Falconer McDonald, had a much less rosy view of swagmen and itinerant travellers. There was no work to be done, and the request to sleep in one of the outhouses to shelter from the oncoming storm was refused. The gang were forced to camp out in the hills, until a torrential rainstorm destroyed their bedding. In Scott’s own words, they “were hungry and thirsty and had nothing with the exception of too much water”. In this hour of misery, Scott made the fateful decision to bail up the station.

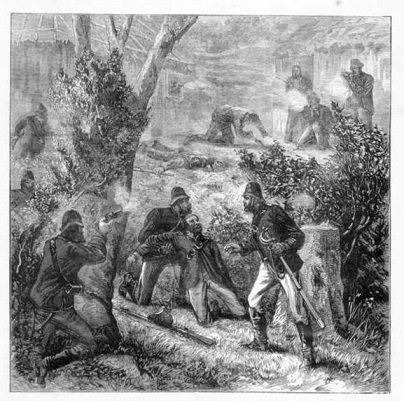

To bail up, in the lingo of the bushrangers, meant to hold captive in order to rob more effectively, and came from the name used for the framework that held a cow in place to be milked. Captain Moonlite intended to milk Wantabadgery Station dry. The gang arrived on foot and took the station manager and the women and children there hostage, and then proceeded to capture McDonald and his men as they returned from their duties one by one. This went well for a while, however Scott does not seem to have thought much beyond his immediate goals. Instead they stayed on the station for two days, capturing everyone who arrived until they had a good forty prisoners, including the local publican who had come calling. Eventually (inevitably) word reached the local constabulary that Captain Moonlite had taken over the station, and they sent out an armed force. The policemen attempted to approach the building surreptitiously, but a barking dog gave them away and shots were exchanged before a tense standoff began. One of the gang set fire to a shed, shouting at the police that he would burn the building with the hostages if they were not let go, but, as one of the police officers recounted “Moonlite said it would be a mean action to burn the man’s property and himself put the fire out”. The police moved to the front of the house, but several of the gang managed to slip through their lines and flank them. The police retreated in a hail of bullets, and the gang stole their horses and fled up the road. They were overtaken by the police reinforcements at McGlede’s Hut, a roadside inn, where they holed up. The standoff lasted for four hours, with exchanges of gunfire resulting in the death of a police officer, as well as two members of the gang. Notably, one was Nesbitt, shot trying to break through the lines and lead the police away from the house. The death of Nesbitt took the fight out of Captain Moonlite, and he was captured. As Nesbitt was dying, “his leader wept over him like a child, laid his head upon his breast, and kissed him passionately”.

Scott’s trial was a huge affair. Wearing a ring made from Nesbitt’s hair, he argued with a great deal of heat that he alone bore responsibility for the criminal affair and begging for clemency for the other three remaining gang members. In this he was partially successful, as two of them received lesser sentences. Scott and the eldest of the gang however, a 21 year old named either Rogan or Grogan, were sentenced to hang for the death of Officer Bowen, the murdered police officer. From his death cell Scott tried to arrange to have himself buried with Nesbitt, writing “We were one in heart and soul, he died in my arms and I long to join him where there will be no more parting”. On the 20th January 1880 Scott went to the gallows, but his wish to be buried with Nesbitt was not honoured by the authorities and he was instead buried in Rookwood Cemetery in Sydney. Finally, however, in 1995 two women living in Gundagai arranged to have Scott’s bones dug up and returned to the town, where they were buried under the shade of a eucalyptus tree in North Gundagai cemetery, next to the final resting place of James Nesbitt. Never to be parted again.

[1] Be aware that the following is based in several parts on the newspaper accounts of his life, and so tends towards the contradictory and often inflated, though I have discarded the most obviously inconsistent.

[2] A disclaimer: both the Italian and American adventures are based on letters Scott wrote from prison near the end of his life, and might be just elaborate lies. However Scott’s exploits in the New Zealand Land Wars are well attested, as is his discharge.

[3] Perry’s main aim at this time was to attempt to adapt the Anglican religion to the situation in Australia, where it was receiving a far lower level of state support than it enjoyed in England.