Burke and Hare, Murderers for Profit

It’s a common misnomer to refer to William Burke and William Hare as “body snatchers”. A body snatcher is one who steals a dead body to sell for profit, but they never stole a body – one they “inherited”, and the rest they made themselves. It’s less common, but equally incorrect to refer to them as “Irish immigrants” – a natural attempt to disassociate from them, but an incorrect one. At the time Ireland was still part of the United Kingdom, for one thing. And for another, both came from counties that remain to this day part of the United Kingdom. Still, it’s hard to blame those who try to insist that this pair must be from some other and (in their opinion) less civilised place. Their crimes are reason enough for that.

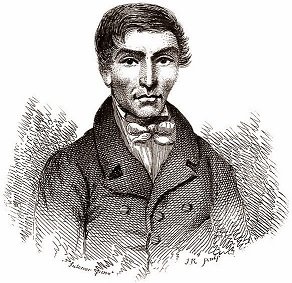

William Burke was born in 1792 in Urney, a townland near Strabane in County Tyrone. His parents were poor, but sought to give their children an advantage through education. At first it seemed that this was working onn Burke, as he was noted as a quick scholar and became a messenger boy for a local clergyman. Sadly it seems this early achievement went to his head, as though he was thereafter apprenticed as a baker, then as a linen-weaver, but both proved to not be to his taste. At his brother Constantine’s suggestion, he joined him in enlisting in the Donegal Militia. There he became an officer’s servant, and during the course of his seven years service he married a young woman from Ballina, with whom he had two children. When he left the army he got a job as a groom and manservant, perhaps based on his military service. However after three years of this he decided to abandon both his job and his family, and head off to Scotland to make his fortune.

At the time the Union Canal was being dug between Edinburgh and Falkirk, and the high wages for navvies drew many like Burke. The money was fairly earned – it was hard work, and dangerous to boot. Burke became acquainted with Helen McDougal, a young woman from a village near the canal. Eventually he persuaded her to run away with him, and the two left the canal and went east to work on the harvest. After that was done they drifted around the country, with Burke unable to settle to any labour. In November 1827 after ten years of this vagrant existence they wound up in Edinburgh, where a fateful encounter with a woman named Margaret Hare took place.

Margaret, Helen and Burke had become friends when the pair previously visited the city, though when exactly that had been is not recorded. Margaret was also from Ireland, having been born near the city of Derry. It’s probable that when last they knew her Margaret had either been under her maiden name of Margaret Laird, or under her first married name of Margaret Logue. Logue had died the previous year, and Margaret had inherited his lodging house. She invited Helen and Burke to come and stay with her, and introduced them to her new husband William Hare. The two Williams had a lot in common – both were former residents of Ulster who had come to Scotland seeking a better life – and the two immediately hit it off. Hare’s origins are somewhat murkier than Burke’s, but the most likely account has it that he was born just outside Scarva in County Armagh, and like Hare wound up in a life of service. In his case it was to a lock-keeper on the canal near Poyntzpass in Armagh. His job mostly consisted of driving draught-horses who hauled boats on the canal, but when he killed one of them in a fit of anger he was forced to flee to Scotland to avoid facing charges. There he met Logue and befriended, and after Logue died [1] he married his widow. She kept the guest house while he worked at day labour in the city.

A few weeks after Burke and Helen moved in to the guest house in Tanner’s Close, an old army pensioner who had been staying there suddenly died. He was in arrears on his rent to the tune of £4, a pretty hefty amount (around four hundred pounds or so in today’s money). The two had heard that the surgeons at the university would pay good money for corpses to dissect, so they stuffed the old man in a crate and carried him down. There they sold the corpse to an assistant of Doctor Robert Knox for seven pounds and ten shillings. Knox was an ex-army surgeon with an uncompromising personality that won him few friends. He had joined the Royal College five years earlier, and now made a great show of public dissections. As such he was always in need of cadavers, and the assistant (who probably had no doubts that the body had not been obtained legitimately) almost certainly dropped hints that future business would be welcomed. Of course, he doubtless expected the two to take to body snatching. He could not have suspected that they had a far more sinister idea in mind.

Their first victim was a sickly tenant at the guest house, who they decided was worth more sold to the surgeons as a corpse than as a paying guest. So they suffocated him, crated him up and dragged him over to the doctors. After that success, they grew bolder. In February 1828 they met an old woman named Abigail Simpson, visiting from the countryside, and persuaded her to stay in their guesthouse the night before she left. Needless to say, her stay in Edinburgh was prolonged indefinitely. So their bodycount grew – one woman was inveigled into the guesthouse by Margaret Hare, who got her drunk and kept her there until her husband got home and finished her off. Another was a drunken woman from the street, who Burke offered to help get home. By the end of the day her body was in the college, awaiting dissection. Their youngest victim was a mute boy of twelve, killed when Hare broke his back over his knee. They nearly made a fatal miscalculation when they chose a local mini-celebrity, a young mentally disabled beggar who was recognised by most of the city as “Daft Jamie”. The boy’s mother began searching through the neighbourhood for him, and several of Knox’s students had heard of this and remembered the lad. When he turned up on the dissecting slab they protested that this was the missing boy, but Knox claimed they must be mistaken. By the time word got out, Knox had rendered the boy unrecognisable.

All told, the pair (or rather, the trio, for Margaret was an active participant) accounted for at least sixteen or seventeen victims in what became known as the West Port Murders. Helen McDougal nearly became one of these victims – Burke later recounted that Margaret had wished to have the younger woman killed and sold, as she felt she could not be trusted. Their final victim was a woman named Mary Docherty, who Burke had decoyed to the lodging house by claiming to be a distant relative. Unfortunately for the criminals she was seen there by James and Ann Gray, two of the legitimate lodgers in the boarding house. Her disappearance made them suspicious, as did Margaret refusing to let them go near one of the beds. They managed to get a look underneath it, and found Mary’s body. They immediately fled the house and informed the police. By the time the police arrived the body had gone. They arrested the four, and soon found inconsistencies in their testimony. When an anonymous tip off sent them to Knox’s dissecting rooms at the College, Mary’s body was found and the jig was well and truly up.

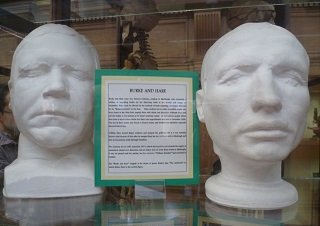

Actual evidence, however, was somewhat thin on the ground. As such the authorities decided to offer the Hares a deal – turn states evidence in exchange for immunity. This was based on their own opinion that Burke was the leading figure in the conspiracy, though it proved massively unpopular with the public. The Hares were both far more villainous looking, and Margaret Hare’s active participation had proved particularly repulsive to the 19th century mindset. Still, the deal was made. In December 1828 Burke and Helen were placed on trial, while the Hares were called as witnesses, but not tried. After hearing evidence, the jury declared Burke guilty. Helen received the peculiarly unique Scottish verdict of “Not Proven” – functionally equivalent to Not Guilty, but expressing that the jury were only held back by lack of evidence. [2] She was released, while Burke was sentenced to first be hung for murder, and then, under judicial order, to have his body delivered up for dissection by Knox’s rival in Edinburgh Royal College, Doctor Alexander Monro. His skeleton is still on display in the college.

The other four people involved in the case may have escaped legal retribution, but all faced the anger of the public. Knox had managed to prove to the police that he had no knowledge of the provenance of the bodies sold to him, but shortly after Burke’s execution in January 1829, a mob attacked his house, breaking windows and burning him in effigy. He was also out of favour with the College, and though he managed to hang onto his position his prestige suffered greatly. In 1837 he applied for the position of Professor of Pathology, only to be told that they were so set against him getting it that it would be dissolved if no other candidate was available. Eventually, in 1847, he was driven out of practice in Scotland and forced to move to London. A popular children’s skipping rhyme immortalised him as part of the crime:

“Burke’s the butcher,

Hare’s the thief,

Knox the boy that buys the beef.”

Helen McDougal may have been exonerated in court, but the public found it hard to accept she was without guilt. The evening after she went home she was attacked by a mob, and taken into protective custody. However this resulted in the police station becoming the target of the mob, so she was dressed in men’s clothing and smuggled out. She left the city and headed home to Stirling, but found no welcome there either. She fled south to England, being recognised and driven out of Newcastle. The last recorded sighting was of her being sent across the border to County Durham.

The Hares were under no illusion that they could stay in Edinburgh, and lost no time in getting out of the city. Margaret Hare (and her infant child, born shortly before the trial) was, like Helen, attacked in the street and take into police custody. She headed to Glasgow (though her husband was still in prison), but eventually the police had to move her to Greenock and put her on a boat to Belfast, where she could travel to her family home in Derry. Hare, upon being released in February, was immediately taken to the mail coach to Dumfries. There he might have hoped to follow her, but he was recognised and a mob of 8,000 attacked the inn where he was staying. The police managed to draw part of the mob off with a decoy coach, and a force of a hundred special constables dispersed the rest. Hare was taken to the southern road out of town, and ordered to head across the border to England. He headed to Carlisle, where he was spotted outside of town.

The last record of him is back where he was born, in Scarva. A newspaper reports that he and Margaret entered a local public house, where some of those present were quick to recognise their town’s most infamous son. He and Margaret were thrown out of the bar, and a group of youths chased Hare across the fields. The newspaper report ends by noting that Margaret and Hare were said to be staying with an uncle of his in the small nearby village of Lough Brickland. Though popular legend had it that Hare was thrown into a lime pit by a mob and ended his days as a blind beggar on the streets of London, there’s nothing to suggest that he and Margaret did anything other than live their lives out in obscure opprobrium in County Down. In fact, the scariest aspect of the West Port Murders may be that the majority of those guilty of them managed to avoid the consequences of their deeds. A terrifying prospect indeed.

Banner via STV Edinburgh.

[1] Given later events, it’s hard to regard Logue’s death without suspicion.

[2] In fact, Not Proven was the original acquittal verdict in Scottish law, and Not Guilty was added later to cover cases where the jury felt the balance of evidence was against the person charged, but they did not believe them capable of the crime.