Cheung Po Tsai and Ching Shih, Pirate Monarchs

It’s hard sometimes to separate myth and legend from the truth. This is especially applicable when one is dealing with pirates, who by their very nature are unlikely to record accurate details of their dealings. That the pirate fleet that ruled the South Chinese Sea were beyond the remit of civilised society is undeniable. That they were led and held to a strong code of obedience is well attested. But as to who held those reins at the height of their power – that tends to be disputed.

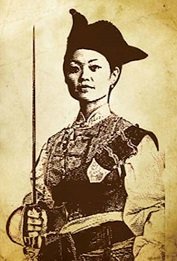

One contender for that role is the woman best known as Ching Shih, who was born in 1775 in Guangdong Province. Her birth name is generally given to be Shi Xianggu. Under that name she became a prostitute working in the coastal city of Guangzhou, capital of her birth province. In 1801, at the age of 26, she was married to a pirate lord named Cheng. There are various accounts of how this happened. Some stories are that he became infatuated with her after a visit to a brothel, and had his men raid it to secure her. Another story is that she was the one running the brothel, and their marriage was the result of a carefully discussed contract that guaranteed her a measure of authority in Cheng’s fleet. She was definitely granted a share of the leader’s role and treated as an equal by her husband. In order to emphasise this connection to the men placed under her command she took the name of Cheng I Sao – “Wife of Cheng”.

Cheng commanded a fleet of uncertain numbers, but probably around 200 ships strong. [1] His family had been pirates for generations, and his name commanded a great deal of respect. It is said that is was his wife’s advice to use this name to to draw together the various pirate fleets of the South Chinese Sea beneath his Red Flag Fleet’s banner. Whether it was or not, he began to draw many lesser commanders to serve under him, and his fleet grew prodigiously. By 1804 some reports claim it had trebled in size to 600 ships, while others put it at a “mere” 300 ships. Each of these ships would have been crewed by between fifty and a hundred pirates, who included women and children as well as men (piracy being a family affair, after all). Some estimates have the Red Flag Fleet at the height of its power later in the decade reaching 1,800 ships strong – not unreasonable, given what it would accomplish.

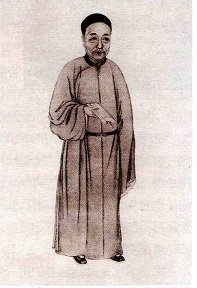

The future pirate king Cheung Po Tsai had been born a fisherman’s son in Jiangmen city in 1783, but at the age of fifteen he was kidnapped and pressed into service in Cheng’s fleet. His natural talent helped him adapt well to his unplanned new career, and he rose swiftly through the ranks. He caught Cheng’s eye, and some rumours have it that the pirate ruler took the young man as a lover. He did definitely take him on as a protege, and at some point he and Cheng I Sao adopted the young man, making him Cheng’s legal heir. The Red Flag fleet grew into a genuine naval power. Then in 1807, Cheng died.

Some stories say he died in a typhoon. Some say he died in an accident, falling overboard. Some even point their fingers at his wife, or his new heir. Whatever the reason Cheng Shih (the “widow of Cheng”) had to act fast before the empire she had helped build fall apart. The first step was to solidify a partnership with Cheng’s official heir, Cheung Po Tsai. The partnership soon became intimate, despite the fact that legally she was the younger man’s mother. The pair’s first success came when they secured the loyalty of Cheng’s relatives, who were all leaders in the fleet. Another key part of the fleet was Cheung Po Tsai’s lieutenant,a man named Cai Qian. He had strong connections to Western weapon dealers as his wife was an expert in Western weaponry who spoke fluent English. She was known as Cai Qian Ma and became notorious in her own right for her savagery in battle, addiction to opium and sexual licentiousness. Cai Qian used his wife’s connections to supply the fleet with British guns, something which added to the growing tension between Britain and China.

Exactly who led the Red Flag Fleet is a confusing matter. Some records claim that Cheung Po Tsai was the leader and Cheng Shih was simply a means to his ascension. Others claim that she was the true power, and he was a mere figurehead. It’s definite that the Red Flag Fleet continued to grow even stronger under their leadership. They controlled the southern coast of China, holding off the fleets of the Qing government and demanding tribute from the locals.

That tribute came with a guarantee of protection, however. Any pirate who tried to loot or harass a town who had paid tribute (or ships from those towns) was beheaded and buried at sea. That was typical of the code that Cheng Shih and Cheung Po Tsai imposed on their fleet – harsh discipline. Any pirate who disobeyed an order was put to death, as was any pirate who raped a female captive. (Rape in general may have been permissible when raiding a town, however – just in case you forgot these were pirates.) Sex with female captive in general was forbidden – if the sex had been consensual, both parties were put to death (he by beheading, she by drowning). Pirates were permitted to take a female captive as a wife. If that was given, she was no longer considered a captive but rather a member of the fleet, with rights and duties. Those who went ashore without permission, or who stole treasure were also killed – treasure normally went into a communal pot and was divided into shares based on rank. Deserters were not killed, but rather had their ears removed before being paraded before their former comrades to show them the penalty for such a crime. The same rough justice applied to the fleet’s “subjects” – when two towns banded together to send a makeshift army against the fleet, the fleet responding by wiping out both the armies and the towns, killing all adult males they found there.

One big advantage the pirates had over the Qing government was in the technological superiority of their ships. There had never been a great naval tradition in the empire. Most of their fleet were converted merchant vessels, ill-suited for ship to ship combat. Their top rung ships were copies of captured pirate vessels, but they were still vastly outnumbered. The prime mover of the anti-piracy campaign was Ruan Yuan, at the time a junior official but later one of the pre-eminent members of the imperial court. Being appointed to “deal with the piracy problem” was generally a way of derailing a potential rival’s career, but for Ruan Yuan it would be the making of him. His primary pirate-hunter was Li Changgeng, the local provincial commander of the army. Li had harried Cai Qian’s first pirate fleet almost to extinction. In one battle in 1804 he managed to destroy most of Cai Qian’s ships and kill his wife (who fought alongside the men), though the pirate leader had managed to escape to Taiwan. [2] As a result Li’s name had become one to be feared among the pirates. It was a major victory for the Red Flag Fleet in 1807, the same year that Cheng Shih and Cheung Po Tsai took charge, when he was caught by an enemy bullet during a naval battle and died.

Li Changgeng’s death was a boost to the morale of the pirate fleet, but it also served as a wakeup call to the imperial government.Cai Qian became a major target for them, and Ruan Yuan was able to get the funds to have enough of his new pirate-hunter vessels constructed to make a difference. In early 1808 they fought a pitched naval battle with the Red Flag Fleet near Hong Kong. The battle ended in victory for the pirates. The Qing government, swallowing its pride, reached out to the Portugese and British forces, offering them concessions in exchange for dealing with the pirate problem. However the Red Flag Fleet’s numbers and local knowledge left the foreigners as unable to dislodge them as the imperial forces.

The tide began to turn in 1809. The authorities managed to discover that Cai Qian was docked in the coastal town of Wuzhen, in Zhejiang province. The new naval leaders, Wang Delu and Qiu Lianggong, blockaded him into the port and attacked. The battle became the subject of legend, and the stories include the pirates becoming so low on ammunition that they loaded their pistols with silver coins. The mundane story is that cannon shots sank Cai Qian’s ship and killed him, but the legend says that he shot himself with a golden bullet once he realised there was no escape. The same legend says that he, like all good pirates, had hidden a hoard of treasure that was never found.

With Cai Qian’s death it became clear to Cheung Po Tsai and Ching Shih that the writing was on the wall. The imperial government was clearly willing to keep pouring resources into their destruction, and there was no way they would be able to hold out forever. As if aware of this realisation, in 1810 the Imperial government issued an amnesty for all pirates willing to lay down arms. (This may have been something they had planned for a while, but were unwilling to do until Cai Qian, at least, had been defeated.) Cheung Po Tsai led his fleet out for a tense armed standoff at sea with the Qing forces, but they proved unable to resolve their differences. In hope of breaking the deadlock Ching Shih walked unarmed, accompanied by seventeen attendants, into the governor’s office in Canton province. She and Zhang Bailing, the governor, were able to thrash out the details of the pirate surrender. Around 400 of the pirates were ruled ineligible for the amnesty, but the rest would be allowed to walk free with all their loot – including Ching Shih and Cheung Po Tsai. The one major sticking point was that the amnesty required that the pirates pay homage by kneeling before the governor, something their pride and honour rebelled at. However they agreed that the two leaders would be able to do this on behalf of their followers, and the two lovers were able to find a pretext for doing so that would satisfy their honour. In the eyes of the law, they were still mother and son. They asked the governor to dissolve this relationship and allow them to be married, which the governor granted. The two were wed with the governor as witness, and as was traditional at the end of the ceremony they knelt to thank him. Honour on both sides had been preserved.

Cheung Po Tsai had little difficulty securing a position in the Imperial Navy, of course, but they kept him posted well away from his old hunting grounds. The negotiations had included uplifting the two to the aristocracy, “by Imperial decree”. The pair settled down into a respectable retirement with the proceeds of their life of crime – the dream of every pirate. In 1813 they even had their first child, a son. Cheung Po Tsai died at sea in 1822, and his widow moved the family back to her old home town of Guangzhou. There she opened a gambling house and brothel. She lived to see her son grow up and give her grandchildren, and died in bed surrounded by her family in 1844.

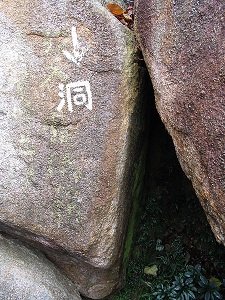

Of course, the lives of these two pirate monarchs soon became legendary. For example Cheung Po Tsai Cave, on an island off the coast of Hong Kong, was named for the pirate treasure that was said to have been stored there. Stories and films based on the lives of the two remain popular to this day, with (for example) characters based on them both appearing in the Pirates of the Caribbean movies. History, as I mentioned at the start, has gone back and forth on which of the two led the fleet – at the time, of course, it was naturally assumed that the man was in charge. As is often the way, the pendulum swung back to far and Cheng Shih was lauded as a “Pirate queen” with Cheung Po Tsai as her catspaw. The truth, as borne out by the historical record, seems to be in the middle. Their negotiation was a joint affair, and once the expedience of commanding the fleet was gone their romance seems to have persisted. It seems that the two had a true partnership of equals – like all the best marriages.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] All of these numbers have to be taken with a grain of salt, of course.

[2] Due largely to internal politics impeding Li. The local Manchu officials resented people like him who came from the capital, and often did their best to undermine them.