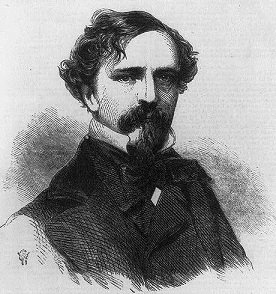

Daniel Sickles, Civil War General and Murderer

Daniel Sickles was born in October 1819 into a well-to-do family in New York City. His father was a patent lawyer and politician, and it was expected that young Daniel would follow him into these trades. In order to help him gain connections, and in an attempt to settle his temperament (which was unsuited to academia), at the age of twenty he was sent to live with the Da Ponte family while he completed his studies. They were an eclectic family – their patriarch had been Lorenzo Da Ponte, a writer (famous for writing the librettos to accompany operas by Mozart and Salieri) and a Catholic priest. Despite his vows, he had several children including a son (also named Lorenzo) and a daughter named Maria. Both Lorenzos were on the faculty at New York University, which had been found in 1831, eight years before Sickles came to live with them. In 1838 the elder Lorenzo had died, and his son became the head of the family. It was the following year that Daniel Sickles came to stay with the household. Maria was the same age as Daniel and rumours did circulate about the two of them having an affair, perhaps fuellled by the fact that Maria’s husband, the conducter and opera composer Giuseppe Bagioli, was 26 years her senior. The pair had been married in 1834, when Maria was only fifteen, and had a daughter named Teresa.

It was his friendship with the younger Lorenzo that bound Daniel to the household, and it was his death that led to him moving out. The stay does seem to have given him both a life-long love of opera and had the effect on his studies that his parents had hoped for, as he first learned the printer’s trade, and then studied law in the offices of the former US Attorney General Benjamin Butler. He also entered politics as a Democrat (benefiting, as many politicians did then, from his party’s tight control of the city through the corrupt Tammany Hall Association). He remained in contact with the Bagioli family, and in 1851 he met the fifteen year old Teresa Bagioli again. He became infatuated with her, and sought her hand in marriage. Her parents, though they were fond of Daniel Sickles, opposed the match. They knew he had a reputation as a ladies man, and more particularly as a notorious user of prostitutes. In fact, he had been officially censured by the New York Assembly for taking a prostitute who went by the name of Fanny White into the chambers as a guest, and had used Antonio Bagioli’s name when arranging a mortgage for her on a property she planned to use as a brothel. In addition to this scandal, despite (or perhaps because of) their own age mismatch, Teresa’s parents had no wish for her to marry a man so much older than herself. (It was around this time that Daniel began giving the year of his birth as 1825 rather than 1819.) Matters were taken out of their hands when young Teresa revealed herself to be pregnant with Daniel’s child. The pair were hastily married first in a civil ceremony and then in a Catholic one officiated by the Archbishop of New York.

Teresa’s parents seem to have been forced to make the best of the affair, but Fanny White was not so sanguine. When she heard of the marriage she turned up at a hotel where Daniel was staying and attacked him with a horsewhip. Still, the two seem to have reconciled eventually, as when Daniel managed to get a post as secretary to the legation sent to Britain under the leadership of James Buchanan in 1853 he took Fanny with him. (Teresa, who was caring for an infant daughter named Laura at the time, was left behind.) In London he took her openly to the opera and to official events, and even introduced her to Queen Victoria herself as “Miss Augusta Bennett, of New York City”. It was her and Daniel’s last hurrah though, as when Laura was old enough to travel Teresa brought her over to London, and Fanny quietly vacated the city. [1]

Daniel returned to America in 1855, and began his foray into national politics. He had an advantage in having been out of the country during the acrimonious debates over the Kansas-Nebraska Act (which had created two new states, and prompted a lot of argument over whether they should be “slave states” or not.) Few politicians in the country had managed to avoid burning bridges and making enemies, and Buchanan (who had also dodged the issue) would actually be nominated for (and elected) President in 1856 as the only candidate who was considered acceptable to all concerned. Daniel was elected as a Congressman for New York the same year, and so the Sickles moved to Washington.

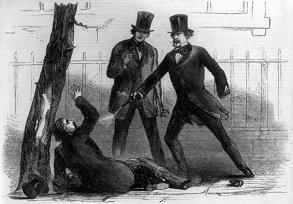

Teresa flourished as a Congressman’s wife, with her relatively exotic Italian-esque upbringing and natural intelligence leading her to become one of Washington’s most celebrated hostesses. Harper’s Weekly (a New York based magazine, of course, and so prejudiced in favour of its daughter) said that she had a special gift for making any guest at her social evenings feel welcome, be he a member of the elite or a countryman fresh into the city. She even became friends with Mary Todd Lincoln, despite their husbands being in opposing parties. In such an environment, and given her husband’s barely disguised multiple infidelities, it seems somewhat inevitable that Teresa began an affair of her own. Her lover was a widower named Philip Barton Key, whose father Francis was well known for writing the lyrics to the “Star-Spangled Banner”. Unfortunately someone sent Daniel an anonymous letter telling him about the affair. He and a friend investigated and gathered evidence, which was not difficult. The pair had been indiscreet, and their relationship was well known in the servants’ quarters. Daniel brought the accusation to Teresa and forced her to sign a detailed confession, then called two of his friends and tried to figure out what to do. Philip, unaware of Daniel’s knowledge, came to the house to try to pass a message to Teresa. On seeing him outside, Daniel ran out and shouted:

Key, you scoundrel, you have dishonored my home; you must die!

He then shot the unarmed man several times with a pistol. Though he was prevented from administering a coup de grace by a bystander, the wounds proved fatal and Philip died within hours.

The trial of Daniel Sickles was a Washington sensation. Despite the fact that Philip Key had been unarmed, public sympathy was very much on the side of a man who shot a man sleeping with his wife. When the time came to select a jury 72 out of the first 75 had to be dismissed for open pro-Sickles bias. In addition Daniel’s connection ensured he had a first-class defence, while the fact that the man he had murdered was the same man who would normally have been the prosecutor in a case like this meant that he was facing an inexperienced deputy. Though Robert Ould (the prosecutor) did his best to point out that a man who takes three pistols out into the street with him has clearly had time to think his actions through, the defence argued that Daniel had acted “in a frenzy”, and managed to shift the focus of the trial to convince the jury that Philip Key was a lecher who “needed killing”. Though Ould could have pointed out the hypocrisy in a man like Daniel Sickles calling a man a lecher, he was probably aware that it would be politically unwise to do so. Teresa’s “confession” (as scripted by Daniel) was ruled inadmissible, so the defence simply leaked it to the press instead. The defence may have pushed for a verdict of either justifiable homicide or temporary insanity, but it was the adultery that they made the linchpin of their case. During the summing up, future Secretary of State Edwin M. Stanton thundered out for the defence:

[Once a wife] surrendered to the adulterer, she longs for the death of her husband, whose life is often sacrificed by the cup of the poisoner or the dagger or pistol of the assassin.

The judge did his best to qualify the inevitable verdict by instructing the jury that any delay between discovering adultery and attacking the adulterer would make a man guilty of murder. It was a wise precaution, as the jury took only an hour and a half to return a verdict of “Not Guilty”, on the grounds of temporary insanity.

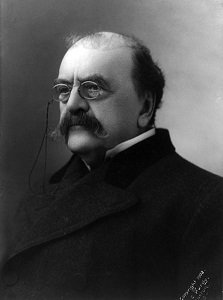

Though Daniel was absolved in the eyes of the law, the trial irreparably harmed his political career. The biggest scandal, in the eyes of the public, was his reconciliation with Teresa afterwards. This led to his conduct during the trial being seen by many as the hypocrisy it was, and the press were scathing in their condemnation. Though he kept his seat in Congress, he largely removed himself from public life. It was the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 that offered him a chance to rehabilitate his reputation. Daniel had always had military pretensions, having bought a commission as a major in the New York National Guard. He had worn his military uniform to formal occasions in London, where the distinction between National Guard and actual Army would not have been apparent. When war broke out he set about organising volunteer regiments in his home city, and he was first made colonel of one of those four regiments, and then Brigadier General above them. Given his lack of military education Congress at first refused to confirm his command, but political lobbying by his allies eventually secured the position for him.

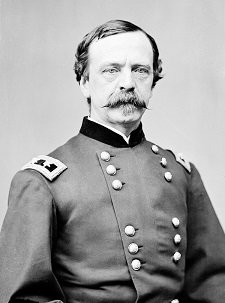

Daniel was originally under the command of Major General Joseph Hooker, like him a notorious ladies man. [2] Daniel’s style in combat was definitely to “go for the glory”, which at first paid of handsomely for him, earning him a promotion to Major General (the only one on the Union side who had not been educated at West Point military academy). He was nicknamed “Devil Dan” – a nickname that could certainly be taken in more than one way. It was at the Battle of Chancellorsville, a notorious Union defeat, that he gained a reputation for insubordination – he didn’t disregard his orders, but he definitely stretched them. This wasn’t the reason for the loss of the battle, but such action combined with a defeat didn’t lead many to have a good opinion of him. [3]

Though he hadn’t disobeyed orders at Chancellorsville, at Gettysburg Daniel opened the battle with an act of rank insubordination. Major General Meade (who Daniel disliked intensely) had ordered him into a position that helped him maintain a solid defensive line, but Daniel (ignorant of the bigger picture) chose to move his troops to higher ground. The result severely weakened the defences of the Union, and when Sickles failed to turn up to a meeting of the commanders, Meade was forced to ride out to his position to demand an explanation. It was too late for him to reposition, as the Confederates were about to attack. In that attack the exposed troops under Daniel’s command were smashed, and his corp were knocked out of the battle. Daniel himself was struck in the leg by a cannonball, and the damage was so severe that the surgeons were forced to amputate it. The injury saved him from a court martial, and being the first of the Union leaders to arrive in Washington (where he was taken for treatment) he was able to bring news of the Union victory and try to put in some preemptive defence against those who pointed out that his actions had nearly led to disaster.

President Lincoln visited him while he was recovering, but Daniel was definitely out of favour. He was eventually decorated for his “bravery” at Gettysburg, but it took him 34 years of campaigning to get that. (This campaigning included multiple vicious attacks on Meade’s character, with Daniel claiming that it was only his actions that prevented Meade from retreating on the first day of the battle.) Though he stayed in the army for the rest of the war, his disability provided an excuse for the professional me to keep him out of a combat command. He donated the remains of his leg to the Army Medical Museum in Washington, where the bones are still kept. After the war he served as a military commander in several districts in the South, before going into diplomacy – first to Colombia, and then to Spain. He was the US Minister to Spain from 1869 to 1874, and despite his disability he soon reasserted his reputation as a lady’s man. There were rumours that he had an affair with Isabella II, the Queen who had been forced to abdicate in favour of her son in 1868. Though she had been exiled to Paris she was allowed to visit Madrid, until it was decided she was “conspiring with foreign diplomats”. If she was one of Daniel’s Spanish conquests, she was definitely not the only one. Teresa had died in 1867, and in 1871 Daniel remarried to a Spanish woman named Carmina Creagh, daughter of a Chevalier.

Carmina accompanied Daniel back to America in 1874, where he became involved in New York politics once again. His daughter (and only child) Laura, who he had fallen out with over his remarriage, died in 1891 at the age of 38. In 1893 he was re-elected to Congress, where he was instrumental in having the Gettysburg battlefield declared a national park. He took a role in designing the park, and it is supposedly at his arrangement that the fencing on the road where he had shot Philip Key wound up transported there and used as part of the boundary of the veteran’s cemetery. It’s notable that he is the only general who fought in the battle to have no monument there, though that may be due to his reputation, or due to his wish to stand out in his absence. He was there for the fiftieth anniversary of the battle in 1913, where he met and embraced some of the Confederate veterans. (Of course, even then he was touched by scandal – he’d been made to resign his position on the New York Monuments Commission, when $27,000 was found to be missing.) The following year, in 1914, he died. His funeral in New York was lavish, as befitted one of the last surviving Civil War generals, and he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honours. No more, as I’m sure he’d have thought, than he was due.

Images via wikimedia except where noted.

[1] Fanny wound up going on a European tour before going back to New York and marrying a lawyer. Her sudden death in 1860 led to allegations that he had killed her for her fortune (which was substantial), but medical examination led to the conclusion that it was a stroke.

[2] While it’s often said that the word “hooker” (as in prostitute) comes from referring to the bevy of camp followers in his camp as “Hooker’s Brigade”, the term is recorded as far back as 1845.

[3] Ironically, two orders he resisted but obeyed (not to pursue scouts he spotted in his area of the battlefield, and to move off his defensive position on Hazel Grove) could easily have led to victory for the Union forces if he’d defied them.