Dudley Clarke, Cross-Dressing British War Hero

There is a booklet written for the British Armed Forces in World War 2 called “All-In Fighting”. It’s perhaps best described as a manual on methods to effectively kill someone else before they can kill you, given in a blunt and unsympathetic fashion. In the postscript, the author William E. Fairbanks dryly comments:

“If you are inclined to think these methods are ‘not cricket’, remember that Hitler does not play this game”.

It was a sobering reminder that in a war like this, all notions of proper behaviour had to be thrown away in the name of survival. Dirty tactics were the order of the day. And nobody exemplified this more than Dudley Clarke.

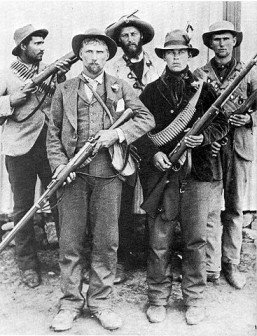

Clarke was born in Johannesburg in 1899, the son of British immigrants. Three years before his birth, his father got drawn into the “Jameson Raid” – a conspiracy by associates of Cecil Rhodes to provoke a revolt in Cape Town (part of the Traansval Republic at the time) and then seize control of it for the British Empire under the cover of “restoring order”. The effort failed, and most of those involved wound up imprisoned, although Clarke senior was lucky enough to escape any short-term consequences. The long term consequences however were not so easily avoided – the Raid was one of the factors that lead to the Second Boer War, which began shortly after Clarke’s birth. His family were among those trapped in the siege of the city of Ladysmith, which lasted three months but ended with them being relieved by the British forces. Perhaps frightened by this experience, the Clarkes left South Africa and returned to England a few years later.

Clarke thus grew up in Watford, where he knew from his childhood that he wanted to be a soldier. Raised on tales of Boer raids, and going to school not far from Aldershot, his path seemed set. When World War I broke out he was eager to enlist, but he was too young to sign up for training until 1915. He passed the entrance exams (he had actually expected to fail and had already formulated a backup plan) and attended the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich. The following November he received a commission in the Royal Artillery Corp, but he was still only 17 and was not permitted to go out to the front. With nothing else to do he applied to join the new Royal Flying Corp (which was a part of the army at the time, but would later become the RAF). Ironically this would wind up in him failing to see any action at all during the war, as his training (first in Reading and then in Egypt) was not finished until 1919. He stayed in the armed forces, however (transferring back to Artillery rather than to the new Royal Air Force), mostly being based in the Middle East. He became interested in amateur dramatics, and began to show a flair for unorthodox thinking. By the end of the 1930s he had drifted into intelligence work, and that was where he was when war broke out in 1939.

At the start of the war Clarke received a promotion to lieutenant colonel, and was officially made an intelligence officer. At first he was sent on whatever missions came up, including a trip to Ireland where he met with the Minister for the Co-ordination of Defensive Measures [1], Frank Aiken, and the chief of staff General McKenna. Britain was worried that the remnants of anti-Treaty forces (from the Irish Civil War of the 1920s) would be suborned by the Germans and used as a fifth column to attack British military industry in the North. [2] Among the topics agreed at the meeting were protocols for Britain to respond if Germany violated Irish neutrality. It was also during this period, following the evacuation at Dunkirk, that he suggested to Sir John Dill (head of the British army at the time) that they form small forces for guerilla-style quick raids, similar to what he had seen done by Arab rebels during the uprising in Palestine. When Winston Churchill called for forces to be assembled to raid the continent and raise morale, Dill remembered Clarke’s proposal. The new forces took their name from the units of Boer raiders that Clarke remembered from his parent’s tales. They were called Commandos.

Clarke was involved in setting up the British Commandos for the rest of 1940. He even accompanied them on their first raid, though he was not permitted to leave the boat. If the creation of the Commandos had been his sole contribution to the war he would still be remembered, but it was his posting in December 1940 that would be his most iconic. Archibald Wavell, who had been Clarke’s commander in Palestine, was at the time directing British operations in North Africa. He specifically requested Clarke to lead a new unit devoted entirely to “Deception”. Clarke’s first operation in this role was technically a failure, though it taught him a valuable lesson. He set out to convince the Italians that British forces would invade Somaliland, rather than their true target of Eritrea. The Italians believed the intelligence, but rather than commit forces to Somaliland’s defence, they instead withdrew them to avoid losing them – moving them to Eritrea. From this Clarke learned that it didn’t matter what someone thought – what mattered was what they did.

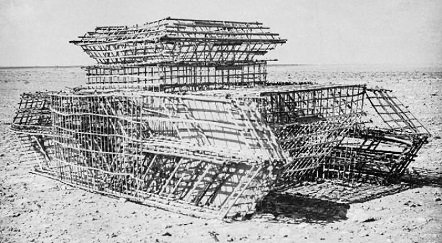

In January 1941 Clarke set about creating his first “phantom army” – the “First Special Air Service”. At the time he knew the Italians had an exaggerated fear of paratrooper attack, and so he set about convincing them that the Allies had an airborne attack force ready to go. He fabricated training exercises, had pictures planted in local papers, and even got soldiers in fake uniforms to visit bars in Alexandria, Cairo and Port Said. The fiction was so convincing that some Allied commanders thought the unit was real. In May, an injured commando named David Stirling conceived of the idea of commando paratroopers, and sought to get Dudley Clarke’s seal of approval for the idea. Clarke thought it a great idea, but insisted that Stirling take the name of his fictional unit and use it for the real one – and so Stirling’s new unit was called “L Detachment, Special Air Service”. The name stuck, and the modern SAS is directly descended from that unit. By the following year more real airborne attack units had begun to appear in North Africa. Clarke wove these real units and his fictional units together to create the entirely fictional 4th Airborne Division, which was highly useful to him in his shell game schemes. In truth, the only real forces in the division were in training, and transferred to real divisions once their training was complete. [3] Eventually the division became part of the fictional British Twelfth Army [4], which was used to convince the Germans of an imminent attack on Greece in 1943 and thus open the door for the successful invasion of Sicily by the real Allied forces.

To aid him in these deceptions Clarke had a staff of highly talented men. The most famous of these were Jasper Maskelyne and Victor Jones. Maskelyne was a third-generation stage magician who would later claim to have been behind the fake tanks that fooled German observers. In truth it was Jones who was responsible for most of these large-scale deceptions, as he had a flair for camouflage and making trucks look like tanks and tanks look like trucks. Maskelyne was of more use in Clarke’s cover operation – running the local branch of MI9, who were in charge of helping POWs in German territory to escape. There his experience in producing props for stage magic helped them develop techniques for hiding useful tools inside mundane objects. Eventually, however, Maskelyne wound up transferred over to the entertainment division, as it was felt his magic tricks were of more use there than on the battlefield.

With Jones and two other capable officers (Captain Ogilvie-Grantshore, who ran the cover operation, and Major E. Titterington, who created the forged documents needed for the deceptions), Clarke had established a strong team, which became known officially as “A Force”. He was able thus to go on side missions for the intelligence service, and it was during on of these (while posing as a war correspondent for the Times) that he had his most infamous escapade. On the 17th October 1941 he was arrested on the Main Street in Madrid, dressed “down to the brassiere” as a woman. The official report depicts Clarke as being unfazed by the arrest, but the Establishment were horrified at the potential for embarrassment and he was quickly extracted and rushed back to London under guard. Unfortunately while he was off the coast of Spain his ship was torpedoed by a U-Boat. Luckily for Clarke he was rescued and taken to Gibraltar, where the governor was possibly more sympathetic than the Londoners would have been. The incident was explained away as over-enthusiasm while chasing down a potential lead, and the chastened Clarke returned to Cairo. It was the last time he would try to do his own fieldwork, leaving that to agents in the future.

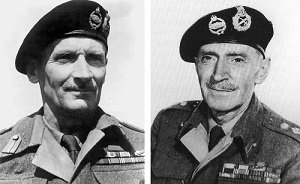

By 1943 Clarke’s deception work had earned him a CBE and a promotion to Brigadier. The work kept coming, however, and Clarke was constantly creating fake invasion plans to keep the Axis from spotting the real ones. The most famous of his operations in this closing phase of the European theatre came in 1944, with Operation Copperhead – better known as the Monty’s Double Affair. Clarke conceived of the idea after watching a film called Five Graves To Cairo, which featured Bernard Montgomery, the commander of the British army in Egypt and Libya, and had him played by an actor with a very close resemblance. After considering how he could use a lookalike, he decided that it would be most advantageous to make the Germans think that Field Marshall Montgomery was in Gibraltar and Algiers, apparently planning an invasion of southern France, while the real Monty was with the Americans drawing up pans to invade Normandy. An actor named Meyrick Clifton James, who was in the Pay Corp at the time, was selected and spent some time with Monty to study his mannerisms before being flown around to play his role. The operation was a success, and would have joined the list of other minor A Force operations, were it not for a post-war postscript. After the operation James was sent back to his original posting with no official recognition, and sworn to secrecy. Ten years later in 1954 he wrote a memoir of the event “I Was Monty’s Double”. The book was a success and wound up being adapted into a film, with James playing both himself and Montgomery. While the film took a lot of liberty with the facts, it did ensure that James (and indeed the deception community in general) received some of the credit they deserved for their part in the war.

After the invasion of Europe in 1944 deception operations were no longer needed, and A Force were unofficially closed down towards the end of 1944. On the following 18th June Clarke called a meeting of his fellow officers in the Great Central Hotel and A Force was officially disbanded. Clarke did not lack recognition for his efforts – he was “mentioned in despatches” in October 1944 when A Force was gradually winding down, and the day after his party at the Great Central he was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath. The Americans also awarded him the Legion of Merit, one of the highest military honours available to non-American personnel. After leaving the army in 1947 Clarke wrote a history of his time with A Force, but despite several attempts he was unable to publish it due to the Official Secrets Act. While he would write several other novels and histories, his tales of deception and skulduggery in service of King and Country were always too much of a departure from the British self-image for officialdom to endorse. It wasn’t until the 1990s, two decades after Clarke’s death in relative obscurity, when the A Force documents were declassified and the truth of his contribution to the war came out. Finally, people could appreciate what a terrible person could do for them.

Images via wikimedia.

[1] A unique rank created in Ireland during “the Emergency”. Aiken (who had been Minister of Defence before the war) ran Civil Defence and censorship, allowing the new Minister of Defence (Oscar Traynor) to concentrate on the Armed Forces.

[2] This did happen to an extent, but they were never very effective.

[3] The 2nd Airborne Division was also entirely fictional, as were the US 9th and 21st Airborne Divisions. The highly mobile nature of airborne forces made them very useful for feints in this manner.

[4] Unlike the division numbers (which were never used for real divisions), a real Twelfth Army was formed in Burma in 1945.