Easter 1916 | Looting and mayhem

As the sun rose on over Dublin city on Easter Monday 1916, few could have guessed it was the dawn of a day that would transform Irish life forever. After the rebellion that burst into flames that day, things would never be quite the same again for the people of the city, and the whole of Ireland.

On that Easter Monday 100 years ago, shopkeepers and business-owners in Dublin city centre were looking forward to the Bank Holiday trade. Excursionists, holidaymakers, soldiers on furlough from the horrors of the Western Front, and ordinary Dubliners enjoying the Easter holiday would undoubtedly make their tills ring all day long. They certainly did not for a second expect to see the denizens of the dank Dublin slums set foot over the thresholds of their establishments.

However, when the trouble erupted, the poor would emerge like a swarm of locusts, descending on shops and commercial premises up and down Ireland’s premier thoroughfare, then called Sackville Street.

Looting on Sackville Street [now called after Daniel O’Connell] began in earnest at around 1.45pm after rebels had successfully repelled an attack by the Lancers, who filed down from the Rotunda. Seeing dead and injured soldiers and horses alike lying in the street acted as a signal for the rampaging hoards to descend on Noblett’s sweet shop on the corner of North Earl Street. The barefoot, malnourished street urchins on previous occasions must have gazed longingly at the ostentatious window display in Noblett’s. Boxes of fine handmade chocolates and various sugary delights would have gazed back at them while they could only salivate and dream of what might be.

It is possible James Hoare possessed the same dream. At 13 years of age, James was in the vanguard of looters who descended on Noblett’s that fateful day. James lived at 25 Cumberland Street North with his mother, aunt and possibly his grandmother. The 1911 Census shows the family also lived together in Merchants Quay. It is highly likely they moved several times between 1911 and 1916 in search of better accommodation. They may have found it at 25 Cumberland Street North, which was classified as first-class building, meaning it was structurally sound.

The 1911 Census recorded that 40 people occupied 10 rooms in this house. It may well seem like the Hoare family had not moved up in the world, but compared to their previous residence at number 14 Henrietta Street, which housed over 100 people, arguably they had. Yet nine out of the 10 families occupying the building where James and his family lived had only one room for themselves. Some people reading this may themselves have memories, or family anecdotes, of life in a Dublin tenement building, others may not. Yet, we all possess imaginations. Let us pause momentarily and try to imagine what would have been like for a 13-year-old in living in Dublin city centre 100 years ago.

Most children spent their young lives roaming the streets of the city. As city dwellers they would have known every nook and cranny, street and laneway alike. If they were not rummaging through rubbish looking for scraps to survive they might have been lucky enough to have a penny to buy a gur cake at the bakers shop. This Dublin staple containing scraps of fruit cake encased in hard pastry was concocted by bakers to sell to children. Today it is seen by some as a delightful Dublin delicacy. One hundred years ago however, it was a treat and a welcome relief from the hard-bitten life they were forced to endure. Living in substandard houses containing outside toilets that were not any better than terrible cesspits, which resulted in untreated sewage streaming through the streets. Death and disease were ever present, the grim reaper lurking around every corner.

People also lived cheek by jowl with Dublin’s vermin population. Infested by lice crawling all over their emaciated bodies they slept with the knowledge that the mice and rats were never too far away. Is it any wonder that the luxurious shops so near yet so far away were targeted by Dublin’s slum dwellers on Easter Monday 1916?

The short and emphatic answer is quite a simple one. Stealing is wrong no matter what the circumstance. At a stretch it may be possible for some to empathise if the looters were stealing food. The rampaging pillage they undertook was indiscriminate and opportunistic. The withdrawal of the police from the streets removed any impediment to this criminal activity. Following the blatant murder of two unarmed Dublin Metropolitan Police officers all uniformed policemen were removed from the streets. The only visible authority were the military and when it became clear to the mob that even they were accounted for the mob were now impervious to any authority setting out to stop them. Shopkeepers and their assistants could only look on in horror as their windows panes were smashed to smithereens. While the fine cut glass was strewn across the pavement, it was not long before a Dublin ‘shawlie’ was observed in the vicinity of Lower Abbey Street with her share of the spoils.

Crawford Hartnell spied

‘a dirty unwashed woman of the slums, ragged and unkempt, with her matted hair surmounted by a fashionable hat – probably three guineas worth – shuffled past, her dirty naked feet thrust into fashionable patent leather shoes.’[1]

However the looters were not confined to the inhabitants of Dublin’s numerous slums. A contributor to the publication Irish Life commented:

‘A remarkable proportion were well dressed and belonged to the wage earning working class, or perhaps to classes still more respectable’.[2]

Two contrasting and illuminating quotes describe the class of looter, yet very little is known about the shopkeepers.

Some simply lost stock; others lost everything. Their stock spirited away by voracious looters, their businesses and homes destroyed by fire, they lost all their possessions, and left only with the clothes they stood up in.

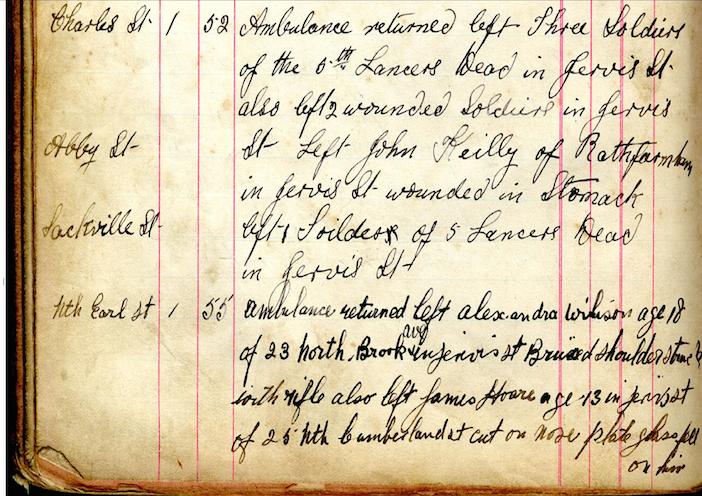

At 1.55pm, James was collected by Tara Street’s Dublin Fire Brigade and deposited in Jervis Street Hospital. He had suffered a cut nose when plate glass had fallen on him. Not only was he present at the precise moment the first shop was looted during the rebellion, but was the first child collected by ambulance during the 1916 Easter Rising.

[1] The Lady of the House, 15th of May, 1916.

[2] Irish Life, Record of the Rebellion, June 1916.