Father John Creagh, Irish Anti-Semite

John Creagh was born in Limerick City in Ireland in 1870. Limerick was a city of strong cultural divisions – it had traditionally been a fortified English city used to control the surrounding area until the relentless tide of improvements in warfare rendered such fortifications meaningless. Still the city retained a large ethnically English and Protestant population, something which caused a great deal of tension down the years. John’s family were Catholic, and like many Catholics in Limerick they were also involved with the Congregation of The Most Holy Redeemer, more informally known as the Redemptorists.

The Redemptorists are a “religious congregation”, effectively a monastic order without the monasteries. They had originally been a European order, but the revolutions of 1848 drove them from their original areas and so the organization had moved west, into Britain and America. They had come to Limerick in 1851 and established a mission in the city, which had grown into their main chapter house in Ireland. John was educated by the Christian Brothers, and in 1884 he became a postulant – an applicant for entry into the congregation. The same year saw the first anti-Jewish riot in Limerick’s history.

The city had only ever had a handful of Jews in residence up until two years earlier, when the savage pogroms in Russia drove many to (like the Redemptorists) head west in search of sanctuary. They lived quiet and unassuming lives (though behind closed wars they had their own arguments over differences in tradition, not surprising for a group from such a broad area). The riot in 1884 took place on Easter Sunday, with stones thrown through the windows of the Siev family, injuring a woman and child. This was prompted by a gentile maid who had seen Lieb Siev, master of the house, slaughtering chickens according to the “shechita” tradition required to make the animal’s flesh kosher. To her uneducated eyes the ritual seemed like cruelty, and incensed by her description a mob decided to show the Siev family their displeasure with this by throwing stones at their house. The family were badly shaken by this, which seemed to them to be entirely without provocation. The culprits were arrested, with two receiving a month’s hard labour. The attack was condemned by the Cork Examiner, and by the historian Maurice Lenihan who was Mayor of Limerick at the time.

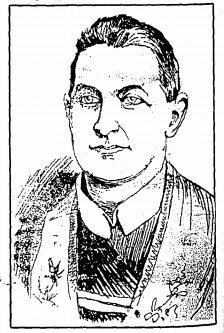

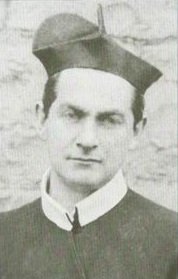

This was not the last incident of its type in Limerick during the 19th century. In 1892 two Jewish men were waylaid and beaten up, while in 1896 another house was stoned. Minor incidents in the grand scheme of things, though traumatic for those who were victims of them. While this was going on John Creagh was progressing in his ecclesiastical career. In 1888 he was professed as a full member of the Redemptorists, and began (as was traditional for the order) studying theology and philosophy. [1] In 1895 he completed his studies and took holy orders as a priest. For the next five years he taught in English universities, and in 1900 he returned to Ireland. He taught history in Belfast at Clonard (a Redemptorist monastery) for a while, and then spent some time in Galway before he returned to his native Limerick in April of 1902.

Father John Creagh was taking on the post of director of the Holy Family Confraternity of Limerick, a Catholic lay association founded and run by the Redemptorists. The confraternity was a sizable portion of the city’s population – around six or seven thousand members (all men) from the city’s thirty-eight thousand residents. (The Jewish population of the city was around sixty or seventy adults, plus children.) It was a position of some influence, and in September of 1902 Father Creagh made his first attempt to wield that influence at a meeting of the city magistrates. On September 26th they were meeting to review and re-grant the license to sell alcohol to the various pubs and premises around the city. Father Creagh made a statement to them on the flagrant abuse of the licensing laws, and the dangers posed by this. The legal opening hour for pubs at the time was seven am (shockingly early by today’s standards), but Father Creagh spoke of men who would knock on the back door of the pub at six am on their way to work and be served. The true source of his ire seemed to be the lack of enforcement of the Sunday morning closures, leading to people arriving at Mass drunk. The magistrates listened politely to his speech, then told him they’d do what they could. Father Creagh knew a brush-off when he received one and left in a foul mood. His mood was apparently worsened by an account in the papers in the papers of his speech, and the following week he addressed the members of the confraterity.

You have been told that drink is the enemy of the Cross, that the drunkard’s god is his belly….and that the drunkard’s end is perdition. I read in one of the papers this week that ‘the conscience of these publicans should be appealed to’. Appeal to their conscience, indeed! What appeals to them is money – blood money- money, the price of souls – the money of Judas. Appeal to their conscience; nothing will appeal to them but the prison cell or the lash of the convict.

It was a striking speech, ending with him extracting a pledge from those present that they would never purchase drink out of hours, and it provoked some spirited debate in the local papers. Father Creagh was supported by the “Limerick Leader”, who praised his “Temperance Crusade”. [2] Though the long term effect of his preaching was debatable, it did have one definite impact. Father John Creagh now had a reputation as a man to watch, and a man of influence.

It may have been a piece in the “Limerick Chronicle” in December 1903 that was the spark for Father Creagh’s next “crusade”. It described a recent Jewish wedding, and the apparent luxury of the ceremony excited a great deal of envy in the community. It’s important to remember that the Jews of Limerick were not just religious but also racial outsiders – immigrants fleeing murderous persecution (in Russia, Jewish villages were being massacred at the time) to a country where historically they had never been persecuted. Like all immigrants, any success they garnered through hard work and industry was regarded jealously by those less successful among the native population. It was a fraught situation, made even more tense by the sublimated tensions between the Catholic and Protestant communities in the town that drove the Catholic underclass to seek out those they could place below themselves. Into this atmosphere, on the 11th January 1904, [3] Father John Creagh delivered a speech to a meeting of the Confraternity that would send his named down in infamy.

The sermon was as fiery as his speech against the publicans, but the substance would have struck a chilling chord with the Jews who had fled the Russian pogroms. For it was the same old tired litany used for centuries to justify their murder. He accused them of “killing Christ”. [4] He claimed that they gained their fortune through usury and cheating Christians (something Christians were more than capable of doing on their own). He accused them of being in league with “Freemasons”, and of being behind the legal changes in France that had secularised education. But his most heinous accusation was one that dated back to the twelfth century AD, one known as the “blood libel”. This innocuous name conceals a truly vile insinuation – the idea that it was a tenet of the Jewish faith that they ritually sacrifice Christian children. It’s possible that this was based on a twisted reading of the story of Abraham and Isaac, but the impact of this medieval fable (invented by an English monk) had always been the same. Whenever a child went missing in a town with a Jewish population, the libel had been repeated and the mob had started to kill Jews. Even as late as 1928, in New York state, when a young girl went missing the local Rabbi was taken down to the station and questioned by the state police. [5] It was an insane and paranoid fantasy of the most ahistorical type, and its repetition brands Father Creagh (despite the revisionism of later historians) as an anti-semitic bigot of the worst kind. But people listened to what he had to say.

They listened, and they acted. Whether they actually believed what he told them or if it only provided the impetus for them to indulge in their own evil inclinations under a false shadow of morality, they acted. Houses and businesses were stoned. Mud was thrown in the streets. Violence was held back, at least for now, but the threat hung in the air. Rabbi Elias Levin, leader of the Jewish community in Limerick, wrote to the retired politician Michael Davitt for support. Davitt was a man with a great deal of prestige. He had been a leading figure in reforming the corrupt laws that favoured landlords and allowed baseless evictions, and was very popular as a result. The previous year he had travelled to Russia to report on the Russian persecution of Jews, and wrote a book exposing the massacres that were going on there. If that wasn’t enough to recommend him to Rabbi Levin, he was also known to be one of the few Irish politicians with no fear of the Catholic church’s influence, as his known support for nondenominational education put him in opposition to their desire to control the education of the young. Davitt wrote a letter denouncing both Father Creagh’s bigotry and his false history, lamenting that it had been a “unique glory” of Ireland that it had avoided the scourge of anti-semitism.

Father Creagh’s response to Davitt was to escalate the rhetoric at his next week’s meetings, quoting anti-semitic passages from a church history written by Rene Francois Rohrbracher. He attacked Davitt directly, but worse was his co-option of a tactic that Davitt’s Land League had developed during the Land Wars of the previous century – the “boycott”, named after a corrupt landlord they had driven from the country. Father Creagh knew that if he urged violence he would face a public outcry, so instead he ordered his confraternity to boycott the Jewish businesses in the city.

The Jews are a curse to Limerick, and if I have the means of driving them out, I shall have accomplished one good thing in my life.

His word was law to them, and they ensured that it was law to the rest of the Catholic community in the city. Some brave souls did have the courage to defy the will of the Redemptorists, but they were few and far between.

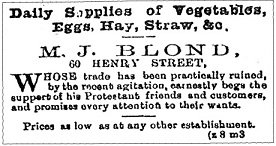

When the scope of the action became clear to them, Rabbi Levin led a deputation to meet the local Catholic bishop, Dr O’Dwyer. He promised them that if they kept the matter out of the papers, he would see to it that Father Creagh would be leashed. The Rabbi kept his side of the bargain, until it became clear that the bishop either would not or could not keep his. In April, Marcus Blond, the formerly prosperous owner of a supply store who faced ruin as a result of the boycott, wrote to The Times laying out his situation. He described how he had built up his business through hard work and honest dealing until Father Creagh’s “hatred and animosity towards the Jews” ruined it all. Now he had no customers, and faced ruin. The letter was his last gasp – by June he had been forced to sell his shop for a pittance and leave Limerick. By the following April he was dead – destitute in London, aged only forty years old and with his health broken by stress.

April 1904 also had one of the few violent incidents of the boycott. A jeering mob confronted Rabbi Levin in the street, insulting and threatening him. One youngster, a fifteen year old named John Raleigh, threw a stone and struck the Rabbi on the leg, drawing blood. He was identified, arrested and tried for the crime, and received a one month sentence in Mountjoy Prison for the assault. The “Limerick Leader”, a local paper that had been a vocal supporter of Father Creagh and the boycott, ran an editorial denouncing the sentence as pandering to the Jews. When John Raleigh returned from his sentence, an adoring crowd greeted him as a hero of the Confraternity. One story has it that he was even given a silver watch to commemorate his “courage”. No such “hero” was willing to stand up and take responsibility for the attack on Sophia Weinronk. Fanny Goldberg, a Jewish woman who was eleven years old a the time of the boycott, recalled the incident later in her unpublished memoirs. [6] Her father and Sophia’s husband David were attacked by a Limerick man wielding a shillelagh, who was later declared insane and institutionalised. David’s leg was broken in the attack, and as a result Sophia, described by Fanny as “such a small little creature”, was forced to go out herself to try and buy food. She was attacked by a group of youths, one of whom “beat her head off the wall” and put her in a sickbed next to her husband. Nobody was ever charged for the assault.

The boycott dragged on for two long years, and drove between half and two thirds of Limerick’s Jewish population from the city. One story has it that a large group headed to Cork to emigrate to America, but received such a warm welcome in the city that they decided to stay there. If the story is true, it shows that some of the Irish people were opposed to the boycott. It is true that a lot of Limerick’s Jews, including Fanny Goldberg’s family, did move to Cork. Standish O’Grady, a prominent member of the Celtic Revival cultural movement, spoke out against the boycott and declared that the Irish and Jewish should consider themselves brothers in adversity. On the opposite side Arthur Griffith, founder of Sinn Fein and noted anti-Semite, spoke in support of the boycott. The Catholic Church refused to take sides on the issue, and Catholic support for the boycott was boosted within the city by an ill-judged speech made in support of the Jewish community by Limerick’s Anglican bishop. The Redemptorist hierarchy too stood behind Father Creagh. In July 1904 Father Mathius Raus, Superior General of the Order, visited Limerick. He received a parade and a civic reception, and passed on a papal blessing to the members of the Confraternity in the city. Rabbi Levin wrote to Father Raus, requesting an opportunity to speak to him during his visit and talk to him about the boycott. His request was denied.

Whether due to mounting public pressure or some internal shift in church politics, the boycott came to an end in May of 1906 when Father Creagh was removed and transferred to Belfast. With trade now open again the Jewish population (those who had refused to be driven out) were able to return to some semblance of normality. Rabbi Levin was one of them. He left the city in 1911 to move to Leeds, where he died in 1936. Father Creagh went out to the Philippines on missionary work – it’s possible that this may have been in recognition of his preaching skills, as the country was a new frontier for the Redemptorists that had been opened to them by the end of Spanish rule. [7] In 1914 he was made Vicar Apostolic (a missionary with the authority of a bishop) to Kimberly in Australia. In 1922 he left Kimberly. Some church records say that he died that year, but those are clearly in error. Instead he went on to be parish priest in various part of Australia and New Zealand, and in 1925 he made a short return visit to Limerick on holiday. He retired from active practice in 1930 after suffering a stroke, and spent his final years in a monastery in Wellington. He died there in 1947.

The Limerick Pogrom, as it became known, remains a controversial matter to this day. Even its classification as a pogrom is controversial, with some historians feeling that this cheapens the horror of the “real” pogroms – massacres taking place in Russia and Eastern Europe at the time. The name was given to it by those who suffered through it, though, and who had suffered in Russia and Lithuania and other countries as well. The situation remained the greatest blot on Ireland’s relationship with the Jewish people up until World War 2, when de Valera’s government refused to allow Jewish refugees from the Holocaust to come to Ireland as they were afraid of Nazi retaliation. Even in 1965, a symposium talking about the event attracted condemnation as an attempt to “stir up trouble” where none was justified. This condemnation soon dried up after the first event of the symposium – a reading of Father Creagh’s first sermon, its bigotry somewhat more apparent after the events which had devastated Europe twenty years earlier. Yet still, in 1970, the Mayor of Limerick Steve Coughlan gave a speech praising the boycott as justified. Some people refuse to admit that their ancestors could have been so wrong. Some still admit that they themselves are wrong. Perhaps one day we’ll look back at the treatment some who seek refuge in our country still receive, and recognise it as just as much of a crime against humanity as the hatred and bile that Father John Creagh peddled. Until then, we can just keep dreaming.

[1] He may have done some of his studies in France, during the period of the Dreyfus Affair – a vicious public debate over the guilt or innocence of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer falsely accused of espionage.

[2] It says something about Ireland at the time that exhorting people not to buy drink before 7am was “temperance”.

[3] Often incorrectly described as a “sermon”, but the 11th was a Monday.

[4] Which has never made sense to me, for two reasons. The first being that it was the _Romans_ who killed Jesus (though it makes sense that the Church of Constantine would downplay that part). The second being that it is a fundamental tenet of the Christian faith that Jesus was sent to earth specifically in order to die and (as the Redemptorist name emphasises) redeem mankind. To single out the Jewish people for the part they played in this divine plan seems somewhat perverse.

[5] The girl was found unharmed the same afternoon, having gotten lost and slept in the forest. Many in the community still insisted that she must have been “kidnapped by the Jews” and that she had been released thanks to their own heroic bigotry.

[6] I haven’t been able to track down Francis Rebecca “Fanny” Goldberg’s unpublished memoirs. This is a shame – she was a Jewish Republican who was a member of Cuman na mBan. Her brother Gerald went on to become Lord Mayor of Cork, and was a member of Cork City Council when the synagogue there was fire-bombed in 1982, an incident related to clashes between Irish UN troops and Israeli forces in Lebanon. (And related to people being idiots.) The synagogue in question closed in February 2016, due to no longer having enough adult male members to carry out regular services.

[7] And thus a reduction in the Dominican presence in the country. Church politics is a messy business.