How Premiership football fulfils Karl Marx’s prophecies

In The Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx argued that capitalism’s greatest achievement was the systematic destruction of tradition. Money or “the icy waters of egotistical calculation” will ultimately triumph over any traditional institution of power such as the church. These institutions start to become tools of the capitalist systems.

As the world enters a stage that many economists would define as “late capitalism”, it’s become increasingly difficult to imagine any other way of life. It’s impossible to picture a world without globalisation, mass production and rabid, if not feral, scientific advancement. Because these are so complex and intertwined, it can be difficult to work out if Marx’s predictions of capitalism’s endgame came through. Something that works as an interesting microcosm to monitor closely the effects of capitalism is how far English football has come over the past twenty five years or so.

Most, if not all, of the clubs that dominate the premiership today grew out of places of employment in the early 1900s: Stoke City grew out of apprenticeship in North Staffordshire Railway, factory workers in the Thames Ironworks founded West Ham and Arsenal was born out of Woolwich Munitions. With an increasing amount of free time for workers, the sport exploded at the end of the nineteenth century. The early years of league football come across as remarkably similar to a cottage industry: clubs created by and for workers. The Football Association, founded in 1883, in many ways was like a guild, existing to regulate and administer a league.

In The Ball is Round (2006) David Goldblatt states that the point of the FA was to keep the sport free from “politics, planning and commercialism”. For decades the sport’s main source of income, television rights, was easy to regulate purely because of the lack of television stations. At the beginning of the 1990s this began to change. Sports broadcasts via satellite television were proving to be successful, in terms of finance, in Europe, and 10 top English clubs openly mused on the idea of breaking away from the FA to set up their own league, a league that would embrace satellite.

The dark days of the 1980s

Realistically, the FA had little choice at the start. The 1980s had been a particularly dark period for English football, marred by crumbling stadiums, hooliganism and racism. English clubs were banned from Europe, and the game was in a bleak state, with an almost desperate need for a facelift. Satellite television presented this opportunity. Television rights were sold to media baron Rupert Murdoch for £304 million (Sky and BT paid around £5 billion last year to retain rights until 2019). Rebranding it “the Premiership” and charging fans to watch supposedly attracted a new air of respectability, but the massive cash injection meant that stadiums and facilities underwent much needed improvement. In essence, this was football’s industrial revolution.

Marx argued that while capitalism represented a triumph of logic over the fundamental nature of feudalism, it would start to have negative effects on society as a whole if left unchecked. Capitalism, with no exception swaps abstract ideals for cold hard results. The almighty dollar has “resolved personal worth into exchange value” and what a person does for a living is valued by its “paid wage” before anything else. Reducing everything to its monetary value effectively means that everything is up for sale. While this no doubt helps a business flourish, it creates a number of adverse effects on society as a whole. It encourages a gap between haves and the have- nots, it places an emphasis on short-term goals which can often lead to waste, and it invites instability.

On a more individual level, this has a subtly dehumanising effect because the status of an individual becomes intrinsically linked to his or her spending power. It also creates a situation where an individual effectively becomes alienated from what they produce – something that Marx described as a “brutal exploitation”. The Premiership is often described as being a pantomime or a circus, and indeed much of Marx’s thoughts can be seen there only amplified.

How commercialism has changed The Beautiful Game

Goldblatt has argued that one only needs to look at how stadiums have changed to see the impact of commercialism on the sport. While the stadiums are no doubt safer these days, fans are now bombarded by advertisements, to a point where, Goldblatt argues, the ads effectively “compete” for attention. This isn’t limited to space that is designated for advertising, it can be seen nearly everywhere: on referees’ kits, the chairs in dugout stalls, match programmes, the scoreboard and even the ball itself.

Since the advent of the Premiership the price of admission has also risen steadily, with the effect of pricing out some of the sport’s most local – and diehard – fans. John Morris of Aston Villa supporters’ club recently stated that the sport is “no longer for the working man”. The BBC estimates that the cost a ticket has risen by 13% over the past five years, whereas the average cost of living has only increased by about 6%. Liverpool’s been in the news recently over plans to raise ticket prices to £77 (€97.50) a game, a proposal that met widespread ire from fans. Similarly in recent months an online movement started by the Football Supporters Foundation, called “20 is Plenty”, has started to gain traction.

Some stadiums have changed their name to reflect corporate sponsorship (The Emirates, the Eithiad and the DW spring to mind). In a recent article for VICE, Will Magee argued that the modern football stadium was reminiscent of what the anthropologist Marc Auge described as a “non place”, a place felt to have no organic character or atmosphere of its own, a sterile, soulless zone created for maximum profit and efficiency. In a sense, stadiums no longer reflect the area they exist in but rather they’re becoming an extension of a corporation whose primary goal is profit.

Clubs become playthings of the rich, not the supporters, as Marx would see it

Beneath the changes to stadiums lie broader questions about who clubs actually belong to. Since the advent of the Premiership it’s become popular for wealthy businessmen to buy clubs, in the same way they might have bought a prize racehorse in the past. Clubs no longer belong to the people of the area, the most fervent of fans. Leicester City, for example, a club that’s recently been grabbing a lot of headlines and currently at the top of the table, is owned Asian Football Investments. That’s a name so bland and blatantly corporate that it conjures up imagery a George Orwell or William Gibson would use to depict a dystopian future.

It could be argued that this is relatively harmless, that this goes on behind the scenes and that it has little bearing on the game itself. One might even make the case that the commercialisation is for the best, because more money is available to clubs. The flipside is that while there can be huge cash injections, there can also be serious deficiencies, putting the clubs’ very existence in jeopardy.

Teams move from community treasures to global brands

Perhaps the most infamous example of this is the US Glazer family’s purchase of Manchester United in 2003. The Glazers acquired the club by taking out massive loans, and not long after their acquisition the club found itself in massive debt estimated to be around £395 million (at times that figure was closer to £800m). As part of collateral for the club’s debt, the Glazers offered up Old Trafford, United’s iconic stadium. This led to the creation of the Manchester Untied Supporters Trust, a group that is attempting to raise money to give fans a stake in the club again. Other fans went even further and set up a new club, FC United of Manchester. These people were so alienated from something that had physical and symbolic ties to their city that they felt the need to start over. Marx argued that a sense of alienation would become inevitable in a system of unchecked capitalism. Producers, he argued, would become so far removed from what they created that it would become just another commodity for them to covet. Teams have moved from being a part of a community to becoming a global brand.

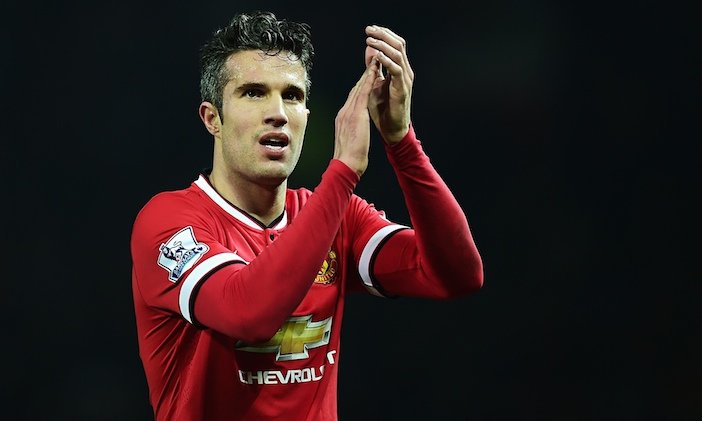

If ticket prices to the Premiership have increased in recent years, something that’s absolutely skyrocketed is player wages. Massive wages have led to an erosion of loyalty, with players transferring to any rival team as long as the price is right. Ten years ago when Thierry Henry captained Arsenal he was so entrenched in the club’s mythology that the idea of him defecting to a rival team like Man United would have seemed absurd. Now, the equivalent happens regularly. At Arsenal alone, William Gallas, Sol Campbell, and Emmanuel Adebayor have all gone to other London clubs, with captains Cesc Fabregas and Robin Van Persie even going to rivals Chelsea and Man United ,for £33 million and £22 million respectively. Elsewhere, Liverpool legend Michael Owen ended his career at Man United, Carlos Tevez (£47m) left United for City, Petr Cech (£10m) and Ashley Cole left Arsenal for Chelsea (£90,000 a week). Fernando Torres spent his time in England looking for whoever could offer him the best deal (which ended up being an eye-watering £55m to move from Liverpool to Chelsea) . Transfers, also, have garnered astonishing sums, with Raheem Sterling’s move from Liverpool to Man City in 2015 costing £55 million (€70 m). (Higher prices have applied to international transfers.)

This has effected managers as well, because everything is examined in terms of its immediate results. No longer given a chance to develop or grow into a role, managers are expected to transform a team immediately. David Moyes had the thankless task of replacing Sir Alex Ferguson at Man U, and was sacked after less than a year for failing to replicate the kind of success that Fergie garnered over his 28-year reign. Louis Van Gaal, while being granted a comparatively luxurious 18 months, now faces similar pressure.

In 2011, following riots that gripped London, Prime Minister David Cameron ignored austerity economics and systematic police brutality, instead suggesting that youth envy of the footballer lifestyle was to blame. In essence this equates the sport wholly with consumerism. While it has been suggested that spending caps be imposed on clubs, or that quotas be introduced to ensure a certain amount of national players are fielded per team (something which has been partially used to explain the international success of Spain and Germany), it’s difficult to imagine this becoming a reality.

Sources:

David Goldblatt, The Ball is Round, 2006

Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto, 1848

bbc.co.uk