“Everything for everyone, nothing for us”

– Subcomandant Marcos.

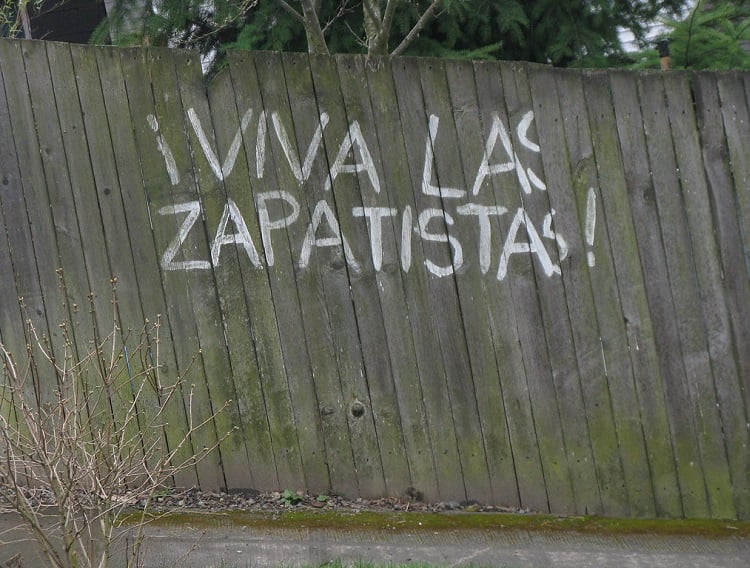

The explosive growth of civil society in recent years has led to the rise of certain groups who have showed the world that real alternative is possible and certainly within our grasp. One of the most innovative, aspirational, and indeed intriguing of these new and radical social movements are the indigenous Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN), or Zapatista Army for National Liberation of Chiapas in south-eastern Mexico. They have arisen from the shackles of five hundred years of colonial oppression and injustice to illuminate to the world that a fairer and more dignified way of living exists. Deborah Greebon describes them as a “unique example of resistance to state repression and the impacts of corporate globalization and neoliberal policy.”

The Zapatista’s cause is essentially the struggle for the human rights that have been denied to the marginalised indigenous population of Mexico through centuries of subjugation. The culmination of this domination lies in the global expanse of neoliberal economic policies through the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which came into effect on the 1st of January 1994. On this same date, San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Ocosingo, Las Margaritas, Altamirano, Chanal, Oxchuc, and Huixtán, seven towns located in the high-lands of Chiapas, had been occupied by an army of over 3,000 indigenous people demanding land, jobs, housing, food, health care, education, independence, freedom, democracy, justice, and peace. It is this battle against the further onslaught of repressive capitalist policies which has led the EZLN to wage war against the unjust practices of the Mexican government and wider global elites, and ultimately against what Alex Knasnabish describes as “a trajectory of racism, neglect, genocide and exploitation.” The Zapatistas were provoked by a repressive system which serves to keep them bound by the restraints of poverty.

In order to understand this revolutionary war waged by the disenfranchised peasants of south-eastern Mexico it is crucial to take the distinctive history of the region into account. All modern nation-states in the Americas are products of the ‘encounter’ between European colonisers and the indigenous populations native to these territories. The rural poor of the Chiapas region have suffered extreme discrimination at the behest of their European colonisers only to be further marginalised by the entrenchment of the globalised capitalist economic system.

Lynn Stephen observes that racial and ethnic categories emerge as part of state discourses used to build nations and to empower certain sectors of a population and disempower others. The echoes of the brutal colonial forces of the past still resound today and are intertwined with the ruthless insatiability which lies at the dark heart of neoliberalism. It is the brutal pursuit of profit and the failure of neoliberalism to adequately address the needs of the most disadvantaged that has led the Zapatistas and other such actors within civil society to step up and offer a new vision characterised by a radical bottom-up governance in the context of resistance and self-development.

These inevitable inequities based on class have led the EZLN down the path of communal resistance and the implementation of an alternative system of governance that meets their needs. The economic desperation of a new generation of young and landless Indians was the product of the lack of alternatives to colonising more land. The final straw for the Zapatistas was the signing of the NAFTA, which was described as a death sentence for the Indians of Mexico.

The NAFTA would result in the binding of Canada, Mexico and the United States together in what would become the template for neoliberal capitalist trade arrangements; and the first day of the ‘war against oblivion’ declared by the EZLN. The indigenous poor would stand to be even further marginalised by neoliberal reforms. By signing the NAFTA Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari had effectively derailed the entire course of Mexico’s revolutionary history.

Deborah Greebon points to the fact that the EZLN uprising was directly precipitated by President Salinas’ 1992 revocation of Article 27 of the Mexican constitution which stipulated the right to communal landholdings. This revocation was carried out in the pursuit of NAFTA and foreign investment, and it disintegrated the last meaningful assurances of community integrity and paved the way for the privatisation of communal land. The signing of this international trade treaty was one of quintessential elements which led the Zapatistas to rise up from the Lancandon Jungle and resist “being absorbed by North American imperialism.”

One of the defining characteristics of the Zapatistas is that they are the first revolutionary movement to declare war not only on a government but on an international trade agreement. The implementation of the NAFTA would serve to obliterate the legacy of the Mexican Revolution and increase the structural inequity of the region. The only real benefactors of this trade agreement would be those at the top of a hierarchal system characterised by wealth concentration. This system was also flourishing in the US and UK under the simultaneous Reagan-Bush and Thatcher regimes. The inherent disproportions of the hegemonic social pyramid and the resultant injustices suffered by oppressed indigenous populations became the driving force of the movement. And the successes of the movement became characterized by its formidable relationship with civil society.

Civil society has come to play a most crucial role in the protection and implementation of human rights. It serves to fill the fundamental void which global capitalism leaves in its wake, while also functioning to counter act the detrimental effects of the globalized free market. Marlies Glasius defines global civil society (GCS) as “people organizing to influence their world”. This resonates with Subcomandante Marcos’ -the figurehead of the movement – eloquent description of the organization of civil society in Mexico:

“Thousands of residents mobilized themselves with nothing more than communal feeling, a feeling that had supposedly been buried in the earthquake of neoliberal modernity.”

Glasius also describes a key contribution of GCS “that of moral values.”

It is with no uncertainty that moral values permeate to the heart of the Zapatista’s cause. It is the strength of their moral and ethical values which has undoubtedly led to the widespread support and admiration from various other actors within GCS.

Instead of concentrating power in the hands of the military, the EZLN sought guidance by actively reaching out to sympathisers in civil society. This strategy demonstrates a unique characteristic of the movement. It was through the mechanism of rejecting the notion of over-throwing the government and instead concentrating on civil society that they began to mobilize international support. In the process of building a system of direct democracy and creating a political space where everyone could participate, the movement was dramatically transformed from a marginal group of revolutionaries to a radical social movement.

The Zapatistas have been so successful at harnessing the power of civil society largely due to the fact that they have proven to be exceptionally proficient with regards to communicating their cause to the wider world. The internet has played a central role in the “networked nature” of the social structure of the movement. The movement succeeded in channelling positive aspects of globalisation in order to counter weigh the extreme negatives of which they were resisting. The Zapatistas movement exemplified the communicative potential of GCS as well as the crucial role played by the internet in the establishment of transnational networks of support.

By January 3, 1994, two days after the uprising, Subcomandante Marcos was online. In the First Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle on the 2nd of January 1994 Subcomandante Marcos communicated to the world exactly why the Zapatistas had taken up arms against the Mexican state:

“They don’t care that we have nothing, absolutely nothing, not even a roof over our heads, no land, no work, no health care, no food or education…”

It was through these communicative mechanisms that they were able to illustrate to the world how dire the situation in Mexico was for the indigenous poor and that they were struggling for humanity and against corruption. The communal nature of the struggle sparked global appeal. Their message which was so aligned with hope and dignity resonated around the world and they achieved a huge global network of support.

The pro-Zapatista movement had huge influence in that it reached across at least five continents and dozens of countries, whereas the anti-NAFTA coalition was only North American in scope. The evolving computer networks supporting the Zapatistas are providing the backbone or nerve system for increasingly global opposition to the dominant economic policies of the present period.

As well as harnessing a high degree of global appeal through their exceptional use of communicative mechanisms the Zapatistas have also engaged a series of strategies and tactics which have resulted in mass global interest and inspiration. Since appearing to the world in 1994, they have laboured the practice of autonomy as a response and alternative to the globalisation of the hegemonic economic order.

In an interview with Thomas Nail, he observes that,

“The intersectional analysis of power, prefiguration, participatory politics, and horizontalism are four of the most defining characteristics of revolutionary struggles of the last 20 years.”

These practices have now become global forces which serve as viable alternatives to neoliberalism. Nail describes ‘horizontalism’ as “the egalitarian gathering of people into popular assemblies and their globally networked connection”. He also argues that it is through this mechanism that the partisan nature of the system of political parties can be surmounted.

The autonomous communities of the Zapatistas exemplify a structure which is in many ways much more progressive and innovative than neoliberalism. The unilateral nature of Zapatista society represents true democracy, a society in which those in power must be subject to the authority of those they serve. Zapatista autonomy is collective, relational, “intercultural”, and centrally concerned with territory, self-governance, and control over resources. The Zapatistas are advocates of local empowerment and communal resistance which is represented through their pluralistic vison of transformative revolution.

The Zapatista movement remains as significant today as it was when the first shots of insurgence were fired on the 1st of January, 1994. Above all they have conveyed that neoliberalism is not the only conceivable political reality.

They have paved the way for an ambitious future characterised by unilateral participatory democracy. They place the well-being of people as the centre of importance in the structure of their political, economic, and social system. This portrays a more logical humane alternative to the reckless pursuit of profit which embodies the neoliberal agenda.

The Zapatistas have attempted to reclaim the lost values of dignity, equality, and human security, which were wrenched from the indigenous people of Mexico through five hundred years of colonial exploitation and the subsequent onset of global capitalism. They have provided the dispossessed and disenfranchised of the world with a voice of strength. They have also expressed that people are not inherently avaricious and materialistic, and that they can exist outside of the neoliberal vacuum. They are an embodiment of the moral code which is relatively absent from neoliberalism. It is the absence of this moral and ethical code which undeniably led to the countless crises which human history has bared witness to, for example, the global financial crisis of 2008, and the ongoing war on the natural world waged by free-market fundamentalism.

Primarily they have provided various social movements of today with the strategic inspiration they require to proceed. As Nail argues, “… the Occupy movement owes its strategies to many predecessors, although none more than the Zapatistas.”

The Zapatistas symbolise the outlook that is necessary in order to overcome the intrinsic inequalities and adversities that have been weighted down upon local communities by the giants of global neoliberalism. The communal and dignified essence of their cause exemplifies the most noble of qualities of the human spirit which refuse to be disintegrated by a callous establishment. They have helped to pave the way for the future of humanity.