“I am a Widow’s Son” | Ned Kelly and the Jerilderie Letter

Jerilderie was a pivotal place in the lives of the Kelly gang. This is where, in January of 1879 the gang undertook two large armed robberies, the second being in Jerilderie, New South Wales. At this point in time the public were largely supportive of the gang despite the fact that they were responsible for the deaths of three police officers from a confrontation in Stringybark Creek, October 1878. Shortly before the robbery in Jerilderie twenty three suspected Kelly sympathisers were rounded up and arrested leading to public anger and the quick release of the prisoners. At this time, the gang had evaded the police and the letter suggests that Kelly wanted to explain and justify the murders. He seemed at pains to be understood. This was not new: Kelly had a history of writing to the authorities explaining his side of things when he felt let down or misjudged by the legal system.

After the events of Stringybark Creek the ransom for the gang had risen significantly from £2000 to £8000, dead or alive. It is possible that as a result of this, the gang started to become more fearful of being betrayed to the police in return for such a life changing sum of money. This may in part explain Kelly’s words on those who would betray him or his associates. He argued that he had never “interfered with any person unless they deserved it”, though if provoked he would not hold back:

“But by the light that shines pegged on an ant bed with their bellies opened their fat taken out rendered and poured down their throat boiling hot, will be fool to what pleasure I will give some of them and any person aiding or harbouring or assisting the police in any way whatever or employing any person whom they know to be a detective or cad or those who would be so depraved as to take blood money will be outlawed and declared unfit to be allowed human burial their property either consumed or confiscated and them and theirs and all belonging to them exterminated of the face of the earth”.

These strong words make his case clear and would prevent many a have – a – go – hero from trying to take him on, however they also foreshadow future events. On the 25th June 1880 the gang executed a former friend and ally turned police informer Aaron Sherritt. Sherritt was shot dead by the gang even though he had four well-armed police men in his home for protection.

Kelly details how his life, and that of his family, had been affected by disputes with the law for many years. His father was an Irishman, John ‘Red’ Kelly who, at the age of twenty-two, was transported to Van Diemen’s Land for stealing two pigs from his native County Tipperary in 1841. After his release in 1848, he married Ellen Quinn, the daughter herself of Irish immigrants. They went on to have eight children with Kelly being the third. His father died in his mid-forties shortly after being released from another stint of hard labour. This time the six months captivity seems to have wrought damage on his health, leading to his death.

It was not long before Kelly, now joint head of the household with his mother, would attract the attention of the police. When he was around 14 Kelly was arrested after a disagreement over a horse. The Jerilderie letter proclaims his innocence of this and future crimes that marked his teenage years. Aged 15 Kelly found himself in disagreement with, a Mr McCormack who referred to how he could have Kelly “or any of my breed” punished as he saw fit. Although said in a tense heightened atmosphere this still shows the prejudice and stratification of society in existence in the colony. McCormack accused Kelly and an associate, Gould, of using his horse without permission. As the altercation escalated Kelly punched McCormack. This resulted in his first prison sentence. As early as this he suggests that there was a certain amount of prejudice against him from the police authorities. Importantly whilst maintaining his innocence he does make it clear that “I hit him and I would do the same to him if he challenged me”.

Animosity towards the police pervades his Jerilderie letter. This is largely the result of his personal experiences; however it does give one an insight into policing of rural towns in the second half of the nineteenth century. For those from small, poverty stricken communities, often made up of emigrants and those who were transported for acts of criminality, there was long running resentment towards authority. This often manifested itself in the actions of the bushranger, members of the rural poor who eschewed the life prescribed for them and bucked from the yoke of the British legal system for a life of crime in the bush. Immigrants and their descendants often held on to their ethnicity and culture. This is particularly important when one considers that by this point resentment had built up in the general population regarding the amount of manpower and expense funding the attempts to capture or kill the Kelly gang. The police were being paid double time and were working increased hours. Although it would not be surprising that the police would want to hunt down the men responsible for the murder of several of their own, the resultant cost of this actually encouraged sympathy for the gang with many disagreeing with the police focus on them.

Source

This runs alongside the undercurrent of anti-British sentiment that was nourished in the colony. The language and imagery of the Irish man living under British colonialism finds expression in the letter. In a continuation of his anger towards the police Kelly ponders the action he may one day be compelled to take against them.

“I will be compelled to show some colonial stratagem which will open the eyes of not only the Victorian Police and inhabitants but also the whole British army and no doubt they will acknowledge their hounds were barking at the wrong stump and that Fitzpatrick will be the cause of greater slaughter to the Union Jack than Saint Patrick was to the snakes and toads in Ireland, The Queen of England was as guilty as Baumgarten and Kennedy, Williamson and Skillion of what they were convicted for”.

The Kelly gang were active between 1878 and 1880. As the son of an Irish criminal, sent thousands of miles away from his homeland, it is not very surprising that feelings of dissatisfaction and blame towards the British establishment flourished in the new, harsh environment that many found themselves in. It is also important to note that at the time many Irish in Australia would have been living with their own and cultural memories of the Great Famine still raw and exposed. The famine resulted in the deaths of approximately two million from starvation and disease, with another two million estimated to have emigrated. ‘Red’ Kelly and his family arguably fit into the theme of the Irish diaspora; banished from ones homeland for a relatively small matter. How many, after their period of imprisonment was completed, would be able to make the journey home? And even if they could what would they have found there in the years after the famine wrought devastation on Ireland.

[iframe id=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/2LH7FXf66KU”]

For many such as ‘Red’ a seven year sentence meant he would never see his homeland again. In this light it is hardly surprising that Irish (and Irish Catholic) patriotism, often established in opposition to British rule was common in the colony. Kelly questions in his letter,

“What would England do if America declared war and hoisted a green flag as it is all Irishmen that has got command army forts of her batterys even her very life guards and beef tasters are Irish would they not slew round and fight her with their own arms for the sake of the color they dare not wear for years and to reinstate it and rise old Erins isle once more from the pressure and tyrannism of the English yoke and which has kept in poverty and starvation and caused them to wear the enemys coat. What else can England expect is there not big fat necked unicorns enough paid to torment and drive me to do things which I don’t wish to do”.

The Kelly families long history with the police continued when Kelly was a young adult. He was first arrested and tried for theft and assault aged fourteen. He was acquitted but went on to associate with well-known bushranger Harry Power who had been taken to the bush after escaping from Pentridge Gaol. It is likely that Kelly would have been bought up hearing stories of bushrangers and their exploits, which were often highly romanticised, and would have been well acquainted with the lifestyle that came with it. Kelly was given his first prison sentence aged only fifteen.

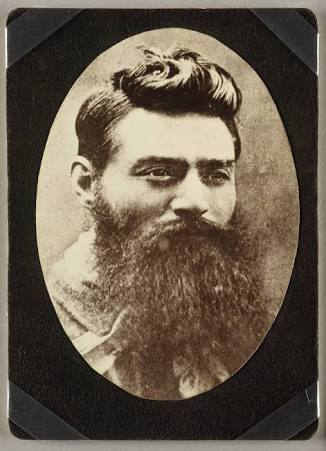

In 1870 he was sentenced to three years hard labour for horse theft. By this time he had become a familiar face to his local police force, having faced and defeated charges multiple times already. One of the few photographs of him from this time show a well-built, heavy set man. His exact date of birth is unsure and many suspected that he was actually several years older by his imposing stature.

This conflict intensified. From the letter it is clear that Kelly felt he and his family had been the target of anti – Irish bigotry and were the focus of continual police persecution; an act by which the wealthier agriculturalists and members of the burgeoning Victorian establishment trod on the poor. However by the time Kelly fled his home for the bush the situation had escalated. On April 15 1878 what has become known as ‘The Fitzpatrick Incident’ occurred in the Kelly family home.

Constable Fitzpatrick visited the Kelly home that night. The reasons for this are disputed but Fitzpatrick stated he was there to issue an arrest warrant to Kelly’s younger brother Dan for horse stealing. What happened afterwards is touched upon in the letter. A fracas ensued and Kelly’s mother Ellen, along with two other associates Bricky Williamson and Bill Skillion were arrested and charged with the attempted murder of Fitzpatrick, who had been shot twice. There is an often repeated myth that this incident occurred because the family were trying to protect one of the younger sisters from Fitzpatrick’s unwanted sexual advances. However this is denied by both Fitzpatrick and Kelly. The constable stated that when he was guarding Dan when two horsemen came up to the property. Kelly then burst through the door and shot the policeman. In the ensuing scuffle he was overpowered by the family; including Ellen. Kelly gives a different version of events in the letter.

He continues with the theme of police brutality and argues that Fitzpatrick pointed a gun at his mother when he came to apprehend Dan. Kelly himself was not on the scene. “The trooper pulled out his revolver and said he would blow her brains out if she interfered in the arrest she told him it was a good job for him Ned was not there or he would ram the revolver down his throat”. As a result of this Williamson and Skillion were sentenced to six years hard labour apiece. Ellen, who was taken into custody along with her baby Alice, was sentenced to three years hard labour. This deepened Kelly’s sense of injustice; he maintained that Fitzpatrick had falsified evidence to ensure that members of his family would be punished.

Even at the time Ellen’s sentence was popularly viewed as being very harsh and unfair. Kelly, who seems to have felt that had he been there the police would not have been so quick to threaten his family had this to say:

“but they knew well I was not there or I would have scattered their blood and brains like rain I would manure the Eleven mile with their bloated carcases and yet remember there is not one drop of murderous blood in my veins … my brothers and sisters and my mother not to be pitied also who was has no alternative only to put up with the brutal and cowardly conduct of a parcel of big ugly fat necked wombat headed big bellied magpie legged narrow hipped splawfooted sons of Irish bailiffs or English landlords which is better known as Officers of Justice or Victorian Police who some calls honest gentlemen but I would like to know what business an honest man would have in the Police”.

It was after this incident that Dan joined Kelly in the bush and he officially became an outlaw.

The letter also exposes the difficulty many former convicts faced in trying to reintegrate back into society. Once he had been labelled a criminal, whether guilty, convicted, or not, it seems almost impossible for Kelly to hold down a legal job. With inevitability, whenever something went missing or wrong, he was the first person to be blamed. This is something he explored in the letter and is an issue that is still pertinent today. Kelly said that he “ran in a wild bull which I gave to Lydicher a farmer he sold him to Carr a Publican and Butcher who killed him for beef some time afterwards I was blamed for stealing this bull from James Whitty Boggy Creek”.

[iframe id=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/ubT2k4rztUM”]

Further to this one line in the letter, an aside to the wider argument against the police feels chilling when read today. In detailing the injustices of certain members of the police receiving high salaries to protect the population that they steal from and brutalise, Kelly had this to say:

“if so why not send the men that gets big pay and reckoned superior to the common police after me and you shall soon save the country of high salaries to men that is fit for nothing else but getting better men than himself shot and sending orphan children to the industrial school to make Prostitutes for the Detectives and other evil disposed persons send the high paid men that receive big salaries for years in a gang by themselves”.

Kelly grew up with his family and did not attend an industrial school, but this one line suggests that there was a general knowledge of the abuses going on against children in institutions at the time. In light of what we now know, this is a deeply troubling line to read. This feeling is heightened by the fact that it is buried in the confession and is only mentioned in order to reinforce the belief in police brutality.

For many Kelly has become a kind of Robin Hood figure; a poor working man fighting against the system. The gang were well known for their good treatment of civilians and hostages. During the final Glenrowan siege it is recorded that no civilian hostages were hurt by the gang and those that did sustain injuries were shot by the police. Near the close of the Jerilderie letter one can see where this idea came from: “all those that have reason to fear me had better sell out and give £10 out of every hundred to the widow and orphan fund and do not attempt to reside in Victoria”.

Ned Kelly’s place in Australian history and culture is undisputed. The worlds very first full length narrative film was about Kelly and the history of his gang. So often in popular culture, despite the dead and prison sentences behind him, he is viewed as one of the last free, wild men; he represents the end of the bushranger era. As Australian society moved inevitably towards a more urban way of life Kelly is often hailed as a reminder of a different, heavily mythologised time. The letter ends on one final message, words underlined for emphasis: “I do not wish to give the order full force without giving timely warning but I am a Widow’s Son, outlawed and my orders must be obeyed”.