Jane Digby, English Adventuress

When Jane Digby was born in 1807, child of privileged English aristocracy, nobody could have predicted the course her life would take. She was the daughter of Captain Henry Digby, a sailor from a line of sailors who had fought against the Americans in the West Indies and against Napoleon at Trafalgar. He would go on to become, like his father before him, an Admiral. Jane’s mother was also named Jane, and she was the eldest daughter of Thomas Coke, a politician and landowner who would become the Earl of Leicester. Thomas only had daughters, and he was rich enough to allow them to marry for love if they wished. He himself was a widower at the time, though he remarried at the age of 68 to a woman fifty years younger. Henry Digby was actually Jane Coke’s second husband, her first having died in an accident, and they married the year before Jane was born. She was Thomas’ first granddaughter, and the apple of his eye. Between Thomas’ indulgence and the money that Henry had made through capturing Spanish ships as a privateer, Jane grew up wanting for nothing.

Jane was the only girl among her siblings, and as she grew up she showed a strong-willed nature that let her get away with all manner of mischief. One preserved note she wrote to her mother reads:

Dearest Mama,

I am very sorry for what I have done and I will try, if you will forgive me, not to do it again. I won’t contradict you no more…You may send away my rabbits, my quails, my donkey, my monkey, etc., but do forgive me.

The menagerie listed illustrates Jane’s main interests – animals, and horse-riding. She had little time for toys. Unusually she received the same schooling as her brothers, and her governess, a forty-year-old clergyman’s daughter named Margaret Steele, managed to turn the wilful ten-year-old girl with clear blue eyes and knee-length blonde hair into an outwardly respectable fifteen year old. Jane showed a particular talent for painting, and Margaret’s elder sister (an accomplished painter also named Jane) joined the household to tutor the young student in the arts. One highlight of these teenage years was a family trip to Italy when Jane was thirteen. Her father, who was a rear admiral at that point, was sent as part of a diplomatic mission and took his wife and daughter (along with a host of servants and the Steele sisters) along. It was this trip that ignited Jane’s life-long passion for travelling. At the age of fifteen she was sent to board at a finishing school for two years, and then she made her “debut” to society. And that, really, was when the trouble started.

At the time Jane had an unrequited affection for her cousin George Anson, who was eight years her senior (which we know about as she preserved the poems she wrote about him). However once she made her debut the beautiful blond heiress became the object of a great deal of interest. One of those who set his cap at her was Edward Law, professional politician and Baron of Ellenborough. He was both handsome and a practiced orator, and he managed to thoroughly turn Jane’s head. Edward proposed to her less than two months after their first meeting, and Jane accepted. On the 15th of October 1822 the 17 year old beauty married the 32 year old Viscount. The Digbys must have congratulated themselves on the excellent match Jane had made. Eight years later, when that same marriage wound up tearing their entire family apart, they would not regard it so fondly.

Though Edward had turned his full attention to Jane during their whirlwind courtship, she soon discovered she would always be secondary to his first love – politics. Edward had been a Member of Parliament originally, for the village of Mitchell in Cornwall. It was a “rotten borough”, with just under forty voters who were all easily bought and paid for. [1] A former MP there had been Sir Arthur Wellesley, until his father’s death gave him the title of Duke of Wellington and a seat in the House of Lords with no need to keep up the pretence of election. Edward too had moved inot the House of Lords when he married Jane, as he had inherited his father’s Baronetcy. Edward had all the right connections – educated at Eton and Cambridge – and he took full advantage of them. By 1828, when the Duke of Wellington became Prime Minister, he had a seat in the cabinet. That was also the year that Jane had her first child, a boy named Arthur. The only problem is that Jane wasn’t entirely sure if Edward was his father.

Quite when Jane began having affairs is unknown, but her husband’s frequent absences gave her plenty of opportunity. The first was with her cousin George Anson, a dashing army man who she had been infatuated with since childhood. It was he who she thought might be Arthur’s father, though her pregnancy led to him immediately breaking off the relationship. She was heartbroken for a while, but then at an official function shortly after Arthur’s birth she met Prince Felix of Schwarzenberg, a handsome Austrian diplomatic attache. [2] Felix was immediately infatuated with her and persuaded Jane to become his lover. However while George had understood the importance of discretion, Prince Felix was used to his station being enough to excuse any behaviour. Jane, it turned out, was still not far removed from the young girl who assumed that any mistake could be undone with a teary apology. The two soon became the subject of malicious gossip, which reached Edward’s ears when a hotel porter recognised Jane and sent him a letter. Once Edward began enquiring, he soon found enough evidence to convince him. Even if he had not, however, it soon became clear that Jane was pregnant again – but given the time she must have become pregnant, there was no way he could be the father. Hoping to minimise the damage to his political career, Edward began arranging an informal separation (which would mean social ostracism for Jane). [3] Discretion, however, was soon blown to the wind. In 1829 Prince Felix, finding himself no longer welcome in polite London society, decided to return to the continent. And Jane, in an unprecedented move, decided to go with him.

It’s hard to comprehend how completely incomprehensible this was to Jane’s contemporaries. Women of her station simply did not do what she had just done – abandon their husbands and their entire lives in order to follow their own path. Edward was forced to divorce her. At the time divorce required an Act of Parliament, and the rate of divorce was incredibly low – only one other divorce happened in that entire year. Jane and Edward’s was not completed until the following year, 1830, by which time Jane had given birth to her and Felix’s daughter, and was pregnant again. The scandal tore her family apart – the grandfather who had doted on her now refused to acknowledge her existence, while her brother Edward wound up estranged from most of his relatives and cut out of several wills simply for taking her side in the argument. The same year as her divorce her eldest son, Arthur, died of cholera. Her husband Edward never remarried, while Jane would never return to the country of her birth.

At the end of 1830 Jane gave birth to Felix’s son, a boy they named Felix after his father. A few weeks later young Felix died, and his death ended his parents’ relationship. Jane moved to Munich, where she had a brief affair with King Ludwig I (who would later go on to become the long-term lover of Lola Montez). While at his court she met Baron Karl von Venningen, and after her affair with Ludwig ended she entered a relationship with him. This resulted in her becoming pregnant again, and to avoid the scandal of a third (or possibly fourth) illegitimate child she left Munich to give birth discreetly in Italy. Karl joined her there, and the two decided to get married in 1834. They had a son, followed by a daughter the following year. Karl was a bit dull for Jane, however, and in 1838 she began an affair with a Greek count named Spyridon Theotokis. The two planned to elope, but unfortunately for them Karl found out and challenged Spyridon to a duel. Karl won, wounding the Greek nobleman, but recognised that this would not be enough to save his marriage. He and Jane agreed to divorce, though they remained on friendly terms for the rest of their lives. He retained custody of their two children, and she set off with Spyridon.

The two first went to Paris, where Jane gave birth to a son named Leonidas in 1840. Jane converted to Greek Orthodoxy and the two were married, moving to Athens. However Jane soon realised that if Karl had been too dull, Spyridon was too much of a hellraiser. He began drinking and cheating on her, and Jane decided that turnabout was fair play. She began an affair with an acquaintance from her days in Munich, a young man named Otto who was the son of her former lover Ludwig I of Bavaria. This was not a low-key affair, however, as Otto just happened to be the King of Greece. He was also married, and his wife, Queen Amalia, was less than thrilled with her husband’s infidelity. Spyridon was also less than happy about it, and when the young Leonidas fell from a balcony and died in 1846 that proved to be the end of Spyridon and Jane’s marriage. Jane took up with Christodoulos Hatzipetros, a general who had been a hero of the Greek wars of independence and who still sought after battle with their former Ottoman occupiers. Christodoulos was as much a brigand as a general, with his men living like guerillas in the mountains and often setting up camp in caves. This was exactly the type of adventure Jane craved, and she soon became an integral part of his plan to provoke a war with the Ottomans when he sent her to Syria to purchase Arab horses for his men. [4] As she set out, however, Jane discovered that Christodoulos had been sleeping with her maid, a French girl named Eugenie. Eugenie had been Jane’s maid for thirteen years, so Jane sensibly decided to keep the maid, ditch the general, and head to Syria with his money in search of adventure.

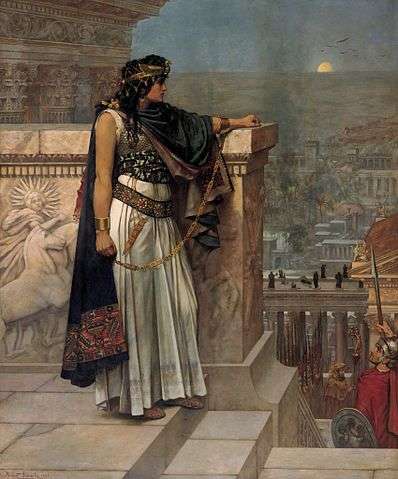

Jane loved Syria – the country, the weather, the people, and especially the history. One story in particular caught her interest – that of Queen Zenobia, who took control of the Palmyrene empire after her husband and stepson were assassinated. She had ruled the eastern coast of the Mediterranean, and held power to rival that of Rome. [5] Unfortunately Rome at the time was led by Aurelian, arguably the greatest emperor they ever had, and he did not brook rivals. Zenobia was eventually defeated and paraded through Rome in golden chains. Her dignity in defeat impressed Aurelian and he granted her a respite from death and a state pension. Zenobia married a Roman senator and reportedly became a prominent philosopher and figure in Roman society, but was never again permitted to return to her homeland. It seems likely that Jane could sympathise.

Jane decided to travel to Palmyra, the ruined remains of Zenobia’s capital, which lay at an isolated oasis in the middle of the Syrian desert a hundred miles east of Damascus. Perhaps she was inspired by the stories of Lady Hester Stanhope, a British explorer who had made the trip nearly forty years earlier. It was an arduous five-day journey across the sands, and caravans which made the journey were frequently raided by Bedouin bandits. European travellers were often held for ransom, if they were lucky. Jane knew that she would need a determined guide, and she found one in Medjuel el Mezreb, the son and heir of a local Sheikh. Medjuel was a famous swordsman and horserider, and he helped Jane organise her party and then led it out into the desert. The caravan was attacked by bandits, but they managed to fight them off. Jane fought alongside the men, and the experience served to bring her and Medjuel closer together. She was 46 years old, and still to some extent a pampered aristocrat. He was a married man in his mid twenties, used to living a hard life on the edge of civilisation. Yet they fell in love – a love, it turned out, deeper and more permanent than any Jane had ever known.

It’s a cliché to say, but it’s true. They really did live happily ever after. Though Jane never converted to Islam, she did adopt the customs of Medjuel’s people, and the two were married under Muslim law in 1854. For half the year they stayed in Damascus, in a mansion among society, and for half the year they lived as nomads, in tents out in the desert. Jane became a mainstay of Damascus society, and was friends with (among others) the British consul Richard Burton, who became famous for spreading the culture of the Middle East back to British society. Jane and Medjuel remained devoted to each other until 1881 when the 74-year-old Jane fell sick from fever, and died in her husband’s arms. She had travelled hundreds of miles from home, and far beyond where she could have imagined herself as a girl, but under the starlit desert sky she had finally found the love she had dreamed of.

[1] In 1831, due to a distressing level of integrity in some residents, the number of voters was reduced to 7 through a process of disenfranchisement. In most cases, this consisted of disqualifying voters who had their vote through being house owners by demolishing their houses.

[2] Jane seems to have had an eye for men of talent – George would go on to become a Major-General, while Prince Felix became Minister-President of the Austrian Empire and is credited with transforming it into one of the Great Powers of the age, while keeping it both independent from but strongly allied with the new unified German state.

[3] Of course Edward had his own string of mistresses, but that was Different.

[4] Christodoulos put his plan into action during the Crimean War, where despite official Greek neutrality he led an irregular force that sought to take Thessaly from the Ottomans while they were occupied. He had mixed fortunes, until the area was occupied by the allied French and English forces and he returned to Greece rather than fight them.

[5] In fact, Zenobia sought to emulate Rome in many ways, taking the title of Augusta as Rome’s leaders did and promoting learning and culture. Oh, and by trying to seize control of Egypt, the richest farmland on the Mediterranean coast.