Marie-Josephte Corriveau

One important lesson for any historian is this: beware of imposing our values on the past. While we should naturally avoid taking on archaic moral attitudes ourselves, we must always remember that the cultures of the past judged things differently from us. So while we can all agree that slavery is abhorrent, for example, we can understand how a man who would call himself a moral and upstanding champion of liberty, such as Benjamin Franklin, could nevertheless own slaves. [1] The converse is also true, however. Some things that we might consider crimes, but not necessarily, horrified people of the past so much that they felt compelled to do things that we would consider barbaric. Such is the tale of La Corriveau.

Marie-Josephte Corriveau was born in 1733 in Saint-Villier, a small town in what is now Quebec, but which at that time was the French colony of France-Nouvelle. Out of ten children she was the only one to survive to adulthood, and her mother, Marie-Francoise Bolduc, appears to have also died some time before 1763. It was a tough frontier, and Marie (like most) married young, wedding a farmer named Charles Bouchard at the age of sixteen. The couple had two daughters and a son before Charles died in 1760. The following year Marie remarried, to a man named Louis Etienne Dodier. The marriage was not a happy one, and both Marie and her father Joseph Corriveau were known to be on bad terms with Dodier. The exact details of their fraught relationship are unknown, however few expected Marie to grieve much when Dodier was kicked in the head by one of his horses and killed. Dark rumours began to circulate, but there it might have ended – if the year hadn’t been 1763.

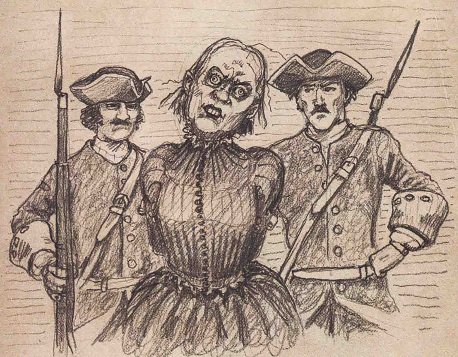

1763 was the year that the British took official possession of France’s North American territories, though they had effectively been ruling the area they renamed Quebec for four years. Still, they were eager to make an impression on the local colonists as a force for order, so they decided to hold an inquiry into the death. The inquiry opened on March 29th, around two months after Dodier’s death, at the Uruline convent in Quebec City. The panel, a committee of twelve British officers, was led by Lieutenant Colonel Roger Morris, an experienced officer who had participated in the capture of Montreal. The inquiry took 11 days, with most of the Corriveau’s neighbours testifying, and at the end of it they decided that Joseph Corriveau had murdered Louis Dodier, that Marie had been an accessory, and that Isabelle Sylvain (a cousin of Marie’s) had perjured herself to protect them. With the force of martial law behind them, they immediately passed a sentence of death on Joseph, while Marie and Isabel were sentenced to be whipped and branded.

The story did not end there, however. Before the sentence of death was due to be carried out, Joseph made a confession to his priest that his daughter Marie had actually been the one to kill Dodier, and he had simply helped her. Whether it was Joseph or his confessor who passed this on to the authorities, they decided to hold a retrial. At this Marie pleaded guilty to the charge of murdering her husband. Her father and her cousin were both released without charge (her father receiving an official royal pardon), but Marie was sentenced not just to death, but to death and exposure. Because by the laws of England Marie was not just guilty of murder, but of the more serious charge of Petty Treason.

Petty treason was a peculiarly English criminal charge that was codified in law in 1351 and abolished in 1828. The basic definition was that it was the murder of one’s superior, and it says a lot about the attitude of English common law to marriage that a wife’s murder of her husband was considered the equivalent of a servant’s murder of their master. (Naturally, a husband killing his wife was not guilty of petty treason.) The official punishment for women was to be burned at the stake, though in the more “enlightened” 18th century the woman would be strangled just as the flames reached her by means of a long leather cord. [2] This punishment would not have been carried out in Quebec as the governeor, James Murray, had ordered that Frech civil law was still to be used for the moment. Still, in the eyes of Roger Morris her crime was more than a simple murder, so instead he ordered that after she had been hanged (as was normal for a murderer) her body would be placed in an iron cage (called a gibbet) and displayed at a crossroads as a warning to others and a reminder of the rule of English law in Quebec, a punishment known as gibbeting.

Gibbeting was, like petty treason, mostly an English invention, and in a similar way it would soon be abolished as a relic from a more barbarous age. It was definitely an unprecedented experience for the residents of the former New France, and the constant sight of a decaying corpse at a busy crossroads seems to have left a significant scar on the psyche of the local culture. After two months and several requests from local people Governor Murray ordered that she be taken down and buried in a local churchyard. This was done, with her body being left in the cage and the whole thing being buried.

Marie lived on in legend, however. Stories soon started that she had killed her first husband as well (though there is no evidence of this), then the stories expanded her number of dead husbands to seven, all murdered by “La Corriveau”, once they discovered that she was a witch. Like all witches, she vowed that the grave would not hold her, and her corpse did not rest easy in the cage at the crossroads. Rather than standing for two months and then getting a Christian burial, instead she was said to have hung at the crossroads for years before disappearing, claimed by the devil himself. Other stories had her ghost float around, still bound within the cage, clinging to the backs of lone travellers and demanding that they carry her across the nearby Saint Lawrence river to the witches’ sabbat on Île d’Orléans.

This local folklore received a major boost in 1849, when the cage in which Marie had been gibbeted and then buried in was unearthed during work in the graveyard at Saint-Joseph-de-la-Pointe-de-Lévy (nowadays known by the somewhat less cumbersome name of Lévis). The cage was placed in the church cellar, but soon disappeared – stolen, so the story went, and sold to PT Barnum for his museum of oddities. The cage was exhibited in Montreal and New York, awakening interest in the local tales that had sprung up over the previous century. The writer Philippe-Joseph Aubert de Gaspé used the legend in his novel “Les Ancien Canadiens”, considered the first great Quebecois novel, with La Corriveau terrorising a passing traveller just as in her legend. James MacPherson Le Moine added the main fictional flourish to Marie’s legend in “Marie-Josephte Corriveau, a Canadian Lafarge”, referring to a French women convicted 23 years earlier of poisoning her husband. In it he made Marie a professional peddler of poisons, even going so far as to say that she was descended from Catherine Monvoison, who in the 17th century had been at the heart of a poisoning ring in the French court. His novel was later translated, combined with several other stories and rewritten by William Kirby in 1877 as “The Golden Dog”, introducing La Corriveau to the English-speaking world.

The motif of La Corriveau in her cage continued to drift through Quebec’s culture, inspiring novels, ballets, painting and music. Even to this day she is referenced, such as in the song “La corrida de la Corriveau” by Mes Aïeux, released in 2001. The cage stolen from the church in Lévis was considered lost – legend had it in “Barnum’s Boston Museum”, with a placard simply reading “From Quebec”, though Barnum had never had a museum in Boston, and no such exhibit could be found in the city. It was assumed it had been lost in a fire, until 2011. That year the Lévis Historical Society discovered it exactly where you would expect to find the cage of a legendary witch – Salem, Massachusetts. The Peabody Essex museum, which had been storing the cage in a back room, loaned it to the city of Lévis for two years, and it remains there today. Those who have gone to see it often remark that, unlike the giant menacing cage seen in drawings of La Corriveau, the harness is heartbreakingly small – barely five feet in height. Like its former occupant, the cage of legend far outgrew the somewhat prosaic reality. Because the truth is that she wasn’t a witch, or a monster, just a woman who took a life, and then paid for it with her own. Her punishment seemed so horrid to the people of the time that it’s not surprising they inflated her crime to fit. It doesn’t really matter, though. Whoever Marie-Josephte Corriveau was, the legend of La Corriveau has long since outgrown her, and in the end the skeleton in the cage begging to be taken across the river may be more real than the real Marie ever was.

[1] He did back off from this view later in life and became an advocate for the abolition of slavery, though how much this was genuine remorse and how much was canny Ben spotting the tide of history is hard to say. It was definitely much further than most of his contemporaries came, at any rate.

[2] Unless the cord burned through, which happened on enough occasions that burning as a punishment was abolished under English law in 1790.

When you said “Benjamin Franklin” in the beginning, I’m pretty sure you meant Thomas Jefferson. Though Franklin did own a few slaves earlier in his life, he freed all of them well before independence and later served as president for the first anti-slavery organization in North America.

I’ve updated the footnote on Franklin to reflect the change in his views as he grew older.