The Origin of the World’s Art: Prehistoric Cave Painting

Prehistoric cave paintings are among the world’s first-known and least-understood works of art. At least two hundred painted caves, some dating to as early as 30,000 BCE, have been found throughout the Pyrenees regions of southern France and northern Spain. The paintings primarily depict animals but also include occasional human forms, a variety of non-representational symbols, human handprints, and engravings. In all cases, their meanings remain elusive. The usual tools of the art historian’s inquiry – written documentation, knowledge of the social and political climate of the period, and other art and artifacts to use as comparison – do not exist for prehistoric, illiterate societies or are extremely scarce and similarly not understood.[1] Furthermore, scholars are still debating the reason for the onset of the human instinct to make art. What changed in the course of human history that led to the creation of these caves and works like the Venus of Willendorf (c. 28,000-25,000 BCE), when previously no art seems to have been created? What function did cave art serve in prehistoric society? Many theories have been suggested, along with several different methods of interpreting the evidence at hand, but a consensus has yet to be reached in over a century of study.[2]

Part of the reason for the difficulty in interpreting cave paintings is the fact that scholars still know relatively little about the prehistoric societies responsible for them. Excavations in the regions where the majority of European painted caves are located have turned up important archaeological materials including tools, hunting implements, small-scale sculpture, burial arrangements, and animal remains, but only a certain amount can be inferred from these findings and little can be proved with any degree of certainty. Since the images recorded on cave walls are closest things we have to surviving records or narratives from these pre-literate societies, scholars run into something of a catch-twenty-two when attempting to interpret them because narratives and records usually inform most art historical interpretations.[3] Some researchers have attempted to fill in gaps in the knowledge base about the place of cave art in prehistoric French and Spanish societies by drawing analogies with tribes like those in Australia who still produce cave art today, while others have argued that there is absolutely no reason to assume that such paintings serve the same or similar functions cross culturally.[4] However, comparisons drawn from the archaeological record can at least provide tantalising possibilities to explore, even if many will prove difficult to conclusively prove or disprove.

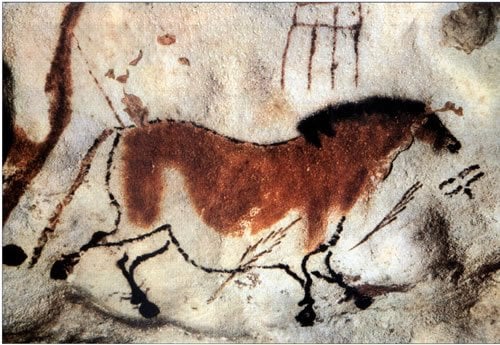

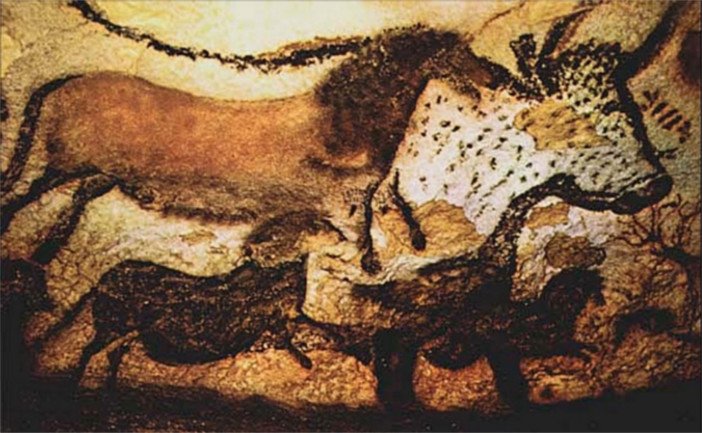

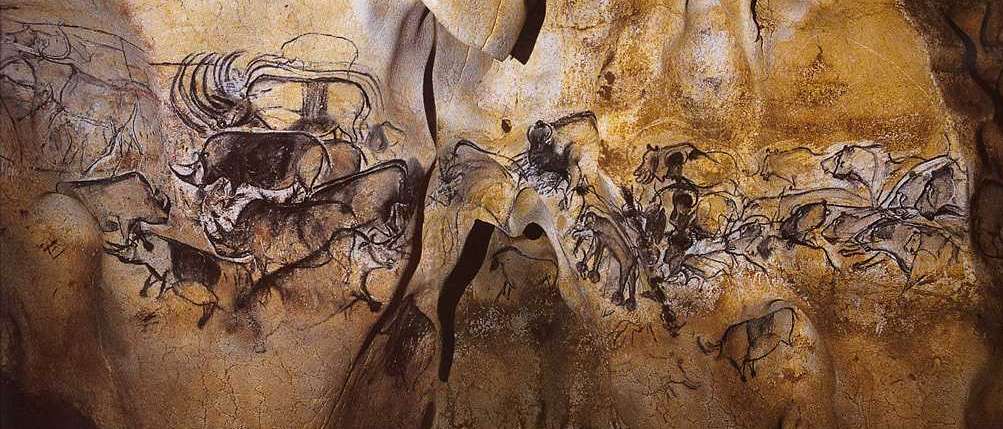

Like most other aspects of prehistoric European culture, the precise nature of the religious practice of the tribes who practiced cave painting remains a mystery, yet it is highly probably that these practices and beliefs were closely tied to the function of cave art. Some potential interpretations take the view that cave art was important for its existence and content, while others assert that its primary significance was in the ritual act of painting or engraving it. It is frequently suggested that the animal images may have related to some sort of hunting magic. Hunting was critical to early humans’ survival, and animal art in caves has often been interpreted as an attempt to influence the success of the hunt, exert power over animals that were simultaneously dangerous to early humans and vital to their existence, or to increase the fertility of herds in the wild. Images that seem to have been clawed or gouged with spears support the former two ideas, while a pregnant-looking horse painting in the Lascaux cave supports the latter. Such imagery has also been interpreted as depictions of shamanic rituals, tools in the conversion of shamans into and out of animal forms, or representations of experiences during shamanic or other ritual trances. An image of a half-man half-stag creature from the Les Trois-Frères cave in France seems to support this hypothesis.[5] The variety of non-representational symbols and handprints found in some caves have at times also thought to have been involved in coming of age or initiation rituals.[6] Finally, it is possible that cave art served as a kind of record of the mythologies and histories of tribes, their rituals, and their beliefs before writing could serve that purpose. The figural imagery may have recorded a narrative, while the abstract symbols could have indicated records of a more symbolic nature.

Part of the reason that so many suggestions have been made but none have gained widespread acceptance is the fact that little firm evidence exists off which to build a solid argument, but part of it is also the fact that prehistoric European cave art is at once very consistent and quite dissimilar. While scholars have been able to identify patterns in the types of animals depicted, their typical configurations, locations in caves, and so forth, many anomalies are still quite inexplicable. Examples of the more confusing occurrences include similar figures repeatedly painted or engraved over each other, enormous animal forms found deep in the far reaches of the Lascaux cave, decorated cave walls with claw and spear marks, the underwater Cosquer cave decorated with images of marine life, a painted chamber in the Chauvet cave also containing bear skulls and bones in a shrine-like setting, a part-human part-animal figure at Les Trois-Frères, and similar hybrids elsewhere.[7] Other elements like hand prints, outlined hand shapes, and abstract symbols, which appear in more than one cave, are even less understood.[8] Although the bulk of known cave paintings are consistent enough in most ways that some scholars have hypothesised about the existence of some sort of “school” or tradition of painting instruction that would account for the similarities in images made thousands of years apart, there is still a high degree of variation in the stylistic attributes of the images.[9] The colours, scale, perspective, shading or lack of, naturalism, and detail in many cave paintings vary from simple, monochromatic line drawings to complex, three-dimensional images rendered naturalistically and in several colours. These variations and exceptions to known patterns are difficult to account for because each seems to suggest a completely different interpretation, and the lack of a firm theory about the meaning of the patterns makes it extremely difficult to understand the significance of any particular deviation.

One question that was once a point of extreme contention but has since been resolved is the age of the cave paintings. Initially, scholars tried to date the caves stylistically, meaning that they attempted to assign dates to works of art based on their similarities and differences in comparison to other works. This is a common practice in art history, but it is typically used when some objects have already been firmly dated using other means, so that other objects compared to them can be placed in an already solid timeline. Before the advent of radiocarbon dating, there were no objects firmly dated, so all proposed dates were speculative and often, on dubious ground. In the study of prehistory, most scholarship was once dominated by the idea that evolution explained everything – that tools and hunting implements became more sophisticated throughout time and that the most naturalistic cave paintings must be younger than the more abstracted ones. This theory was abandoned when advances in the scientific dating of objects produced a more reliable set of results that often completely disagreed with the results of dating via an evolutionary methodology. Also, in the realm of art history, the advent of formalism and abstract art has gone very far to do away with the assumption that naturalism is the end goal of all art and artists, opening up the possibility that ancient artists may have chosen to paint non-mimetically at times and mimetically at others.[10]

We may never know the full story of how and why prehistoric humans painted so many powerful images inside caves, but their mystery should certainly continue to be of interest to art lovers and historians far into the future. In fact, as art continues to reinvent itself, as it has consistently done throughout history, the question of exactly where art comes from and why it has become such a universal element of the human experience should only become ever more relevant.

(1) Davies, Penelope J.E. et al. Janson’s History of Art, the Western Tradition. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2007. 1-6. (2) Davies. Janson’s History of Art. 1-2; Curtis, Gregory. The Cave Painters, Probing the Mysteries of the World’s First Artists. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006. 11, 29-30, 125-127. (3) Davies. Janson’s History of Art. 1-6. (4) Curtis. The Cave Painters. 64-65 & 125-127. (5) Theories about cave paintings’ potential relationship to magic, religion, and shamanism are widely discussed, specifically in Adams, Laurie Schneider. Art Across Time. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2007. 35-39; Davies. Janson’s History of Art. 6-8; and Curtis. The Cave Painters. 65, 116-117, 145, 179-185, & 220-225. (6) Adams. Art Across Time. 35; Curtis. The Cave Painters. 103-104. (7) These occurrences are discussed variously in Davies, Adams, and Curtis. For a detailed description of the painting at Lascaux, including the famous Hall of the Bulls, see Curtis. The Cave Painters. 92-118. For the half-man half-stag at Les Trois-Frères, see Curtis 179-185, and for the bear shrine at Chauvet see Curtis 210-212. (8) Adams. Art Across Time. 35; Curtis. The Cave Painters. 5-6 & 97. (9) Curtis. The Cave Painters. 16-19. (10) For a more comprehensive discussion of the various ways in which scholars have attempted to date prehistoric cave paintings, including stylistically and through radiocarbon dating, see Davies. Janson’s History of Art. 5; Adams. Art Across Time. 39; Curtis. The Cave Painters. 13 & 68-72. SOURCES: Adams, Laurie Schneider. Art Across Time. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2007. | Curtis, Gregory. The Cave Painters, Probing the Mysteries of the World’s First Artists. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006. | Davies, Penelope J.E. et al. Janson’s History of Art, the Western Tradition. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2007.