Artful Historians | 306 Hollywood, Julia Huynh and the Art of Cultural Preservation

History is a presence in everyday life and few would likely combat such a sentiment. However, the actual study of history, namely historical objects, be they visual or material, has long remained an academic endeavour. Yet in the last few decades, this often exclusive realm of historical scholarship has begun to shift through creative practice and innovative activism.

The documentary, 306 Hollywood (2018), directed and produced by New York-based filmmakers and siblings, Elan and Jonathan Bogarin, provides an unlikely medium for exhibiting the accessibility of visual and material culture. 306 Hollywood is receiving international praise for its ability to create empathy and intimacy through a highly stylised form of documentary cinema. Bogarin and Bogarin challenge the established genre of the documentary by intersecting traditional visual narrative with surreal episodes of dance, movement, and existentialism to capture the strange materiality of losing a loved one. This creative approach to documentary filmmaking brings to life objects of the past through the processes of archival and archeological cataloguing, humanising the study of material and visual culture before a public audience.

306 Hollywood intersects filmed conversations with Elan, Jonathan, and their own mother in dialogue with grandmother Annette Ontell, centering the documentary around Ontell’s New Jersey home. Upon Ontell’s passing, the film undergoes an archeological dig of the house and its amazing accumulation of ‘stuff.’ What ensues is the study of decades of clothes, papers, furniture, and odds and ends. Reflecting on their deceased matriarch’s collection of common and extraordinary possessions, the film captures an incredibly personal story, illuminating the often dull and uninviting world of cultural preservation and conservation. Casting themselves as sleuth’s of Ontell’s past and present through artefacts and oral interview recordings, Bogarin and Bogarin reveal to the viewer how all individuals and communities can have their story understood, and even celebrated, through the objects and places we leave behind.

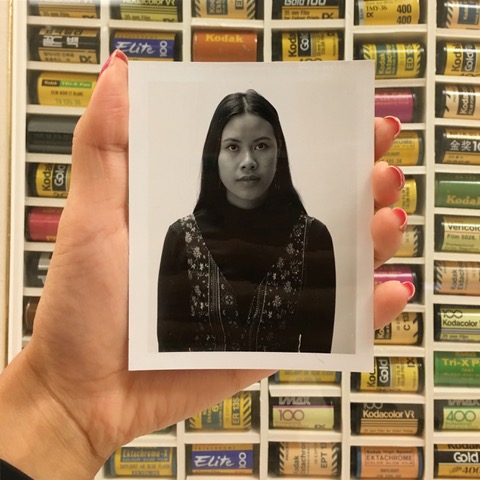

Personal and community-based archives seek to represent this vital aspect of history’s relevance in modern day society. Toronto-based artist and scholar, Julia Huynh, explores innovative archival approaches in her research and creative process. Huynh has a particular interest in Vietnamese diasporic family photographs, both of her own family and those found in community-based institutions and databases.

Daughter to Vietnamese refugees, Huynh articulates the importance of home and familial narratives and recognises visual culture preservation as an entity that can distort but also open up cultural heritage dialogues. Identifying the historical control of the camera in the hands of a White majority, Huynh investigates the intimate and accurate representation which family photographs can provide towards uncovering the true narrative of the Vietnamese diaspora in Canada and the United States. Constructing creative pieces of film and photography in collaboration with personal as well as contemporary and historic collections, Huynh is also expanding the resources found in archives towards equitable representation of communities of colour. Huynh sees her art and research as an act of self-preservation, celebrating, but also confronting, her own family’s story in the foreground of larger commentary and in doing so, linking visual culture to the healing and regaining of cultural pride.

To consider historical scholarship a personal or even creative narrative is a novel and controversial topic of discussion. However, speculative notions should be rebutted in light of the centuries of culturally dominated histories of white skin and elevated social class which has in turn, skewed history in a personal and often, destructive, manner. This critical cultural commentary of archives is being applied artistically in the creation of “false archives.” Huynh looks to The Fae Richards Photo Archives (1996) as an important example of uniting archival studies and creative expression. Crafted by photographer Zoe Leonard and filmmaker Cheryl Dunye, The Fae Richards Photo Archives is a collection of photographs recalling the lost history of a fictional Black actress and singer. Its creation and presence confronts the lack of stories of women of colour in historical collections by creating one, demonstrating the need for archival preservation to recognise its selective past.

Crossing the disciplines of art and history is expanding the possibilities of engaging the past in public and equal spaces. Class and ethnicity have long been dictated by history and often in the production and preservation of material and visual culture. Because the modern human learns and relearns societal constructs through visual and tangible sources in a media-driven consumer age, presenting a calculated version of history allows a detrimental continuum of cultural misinformation and misrepresentation. However, when communities, artists, and scholars alike challenge this problematic pattern, systems of division can become systems of inclusion through the responsive production and preservation of visual and material sources which tell the whole story. Furthermore, principles of authenticity and equity can and should drive professional and personal works of historical reflection.

Preservation scholarship is no longer a veiled academic practice, but it will take brave and creative voices to continue to prove that to the world.