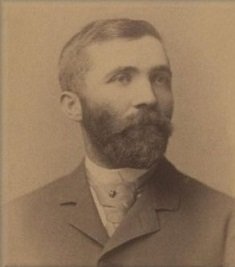

Soapy Smith, Frontier Conman

Jefferson Randall Smith, known later as “Soapy”, was born in Georgia in 1860. His family were reasonably well-off plantation owners, though probably not as wealthy as Smith later claimed. However being a “plantation owner” meant that most of their wealth was tied up in the slaves on their plantations, and when those slaves were freed in 1865 the family were ruined. [1] They sold their land and moved to Texas in 1876. In 1877 Smith’s mother died, and in 1878 he and his cousin Edwin saw a man get shot – the outlaw Sam Bass, who later died of his wounds. The same year Smith left home and moved to Fort Worth, a busy town that lay at the southern end of the railway line. This made it a terminus point for all the cattle drives in Texas, and ensured the town always had a healthy supply of people passing through. The perfect place for young Smith to perfect the art of the bunco man.

Smith had travelled around the country before he came to Fort Worth, selling cheap jewellery for far more than it was worth. He had found in himself a talent for salesman’s patter, and from other men on the trail he learned the grifter’s art – how to run a properly crooked game of three card monte, how to ensure that none of the shells held the pea, and how to leave town just before the stomach cramps from your “miracle cure-all” set in. It was a trick he invented himself that resulted in Smith gaining his name Soapy – the “Prize Soap Package” scam. Setting up a stall ostensibly to sell soap, Smith would hold forth on the wonders of the soap itself before offering his unique sales incentive. First he held up a sheaf of bills, which he showed to include singles, tens, twenties and even a couple of hundreds. Next he wrapped the bills around cakes of his soap, then he wrapped them in paper to make them indistinguishable from the rest of his stock. Finally he dropped them into a bag, mixed them all up, and began selling the soap cakes one by one. The price started at a dollar, and early on one punter would shout excitedly that they had won a hundred. (The winner was, of course, an accomplice.) After the plant there would be no more big winners – though there might be a single here and there and maybe even a five dollar winner to keep the crowd on the hook. As the stack dwindled the price went up, with Smith insisting that the odds were clearly tilting in the crowd’s favour. But in the end Smith left with bulging pockets, while most of the punters went away with nothing more than a nickel’s worth of soap.

In Fort Worth Smith found comrades, and showed that he had a talent for leadership as well as chicanery. Soon he had a tight-knit gang around him, and he was always prepared to stand by his men. He also learned the value of investing in a solid legal team, as even though the Fort Worth legislature passed laws to try and crack down on his swindles, he still managed get out of court a free man. It was during one of these entanglements that the nickname “Soapy” first appears in writing, written by a lawman who either couldn’t recall his first name or never bothered to learn it. Soon enough Soapy Smith got tired of Fort Worth, and he and his gang set off to make their mark in a town with real potential. A town growing far too fast for its lawmen to be able to keep up – Denver, Colorado.

Smith arrived in Denver in 1879, and immediately set about making himself at home. Denver had a laissez faire approach to gambling, even crooked gambling like Soapy Smith ran. This gave him a solid base, and he began to expand. His success came from two key factors. The first was loyalty, and Soapy understood that it was a two-way street. He was always prepared to go to bat for any member of his gang, and knowing that he had their back made them prepared to do anything for him. He had grifters, gunmen and even good solid citizens, for Soapy knew the value of honesty when it suited him. His rules for his men were simple – avoid getting violent, and never mess with the locals. [2] Visitors to the town, and travellers passing through, were fair game. By 1884 Soapy had become the ruler of Denver’s underworld – and a man many in City Hall openly called a friend.

Soapy’s base of operations in Denver was the Tivoli Club, a gambling hall he owned. There were only two honest things in the Tivoli Club – the first was the inscription above the door (”Caveat Emptor”, Let The Buyer Beware), and the second was the Canadian gunfighter Bat Masterson, who once worked as a dealer there. In 1889 Soapy’s brother Bascomb came to town, and Soapy set him up with a cigar store – though the real action was the card game in the back, where prosperous-looking strangers were invited to rest their feet a while. Fake businesses were a speciality of Soapy’s, with a notable example being fake auction houses running simply in order to suck in out of towners to bid on suspiciously cheap (and secretly shoddy) items. Soapy’s gang were very popular with the locals, though. They gained a reputation for generosity (Soapy was active in many anti-poverty movements) and chivalry. In one incident Soapy and his men staged an armed raid on a detective’s office where a female employee of his was being held hostage. Rumours that the detectives were planning to torture the girl and only Soapy’s “heroism” saved her helped to cement his status as a defender of the lower class.

In 1892 a shocking rumour swept through Denver – the council were banning gambling. In response Soapy sold the Tivoli and moved a couple of hundred miles down the trail to Creede. Creede was in the middle of a silver-mining boom, and the easy money drew many a ne’er-do-well to take advantage. Soapy’s advantage in numbers and organisation saw him running the tent city’s underworld within weeks. His most famous con there was his exhibition of “McGinty”, a supposed fossilised caveman. While he didn’t charge people a lot to see the fake Neanderthal, the real money came from the various gambling amusements his men ran for the crowd standing in line. Soapy’s time in Creede was certainly eventful. In June 1892 Creede became infamous for the murder there of Robert Ford, killer of Jesse James. Eventually the government of Denver shifted back to a pro-gambling stance, the price of silver plummeted, and Soapy moved back home.

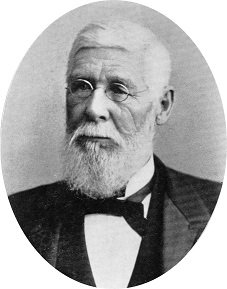

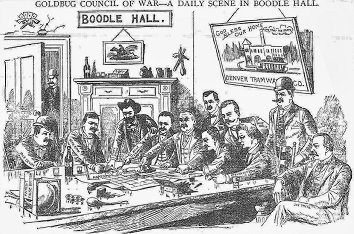

The most notable incident in Soapy’s tenure as crime boss of Denver came in 1894. The year before, Davis Waite was elected as governor of Colorado. Waite was a 19th-century Republican, which is to say he was a good deal to the left of anyone in the current US political establishment. It was thanks to his influence that Colorado became the second state to give women the vote. Waite was determined to clean up Denver if it wouldn’t clean itself up, and his first step was to decentralise the mayor’s power into a municipal board. This didn’t help much, as it turned out six men could easily be as corrupt as one. In 1894 Waite sent a letter dismissing the police and fire commissioners, based on evidence that they had been taking bribes to conceal brothels their services had uncovered. The two men refused to accept his authority, and they and their supporters occupied the Denver city hall in protest. Governor Waite, in no mood to play games, sent in the state militia to root them out. Soapy had brought his men in to support the local officials, and was deputised by the sheriff to lead them. The gang had brought dynamite and rifles to defend the hall, though they were opposed by cannons and Gatling guns. Things could have gotten very bloody if violence had broken out, but the governor eventually calmed down and agreed to take the matter to the courts rather than the streets. The “City Hall War”, as it became known, ended without a shot fired.

Soapy did very well out of this political spat. His friends stayed in power, and they remembered who had stood by them in their hour of need. He was a major witness in the resulting court hearings, and this helped him gain social cachet as a major local businessman. [3] Even the deputy sheriff badges he and his men had received were useful – they used them to stage fake raids on their gambling houses just as some unfortunate whale had been cleaned out, in order to get them out before they could complain. The good times had to come to an end, of course. The main problem was Soapy’s own bad temper, especially when he had been drinking. It undermined the trust his empire was built on, and allowed his rivals to move in. At least two attempts were made on his life, and he eventually decided to leave town while he could with his skin intact. In 1895 he left Denver for the unlikely destination of Mexico. There he somehow managed to get an introduction to the President, and convinced him that Soapy was the right man to set up a mercenary “foreign legion” for him. He had already commissioned himself as a Colonel and set up a recruiting office before the Mexican authorities finally found out what type of man he really was and shut him down.

How they found out was down to Soapy’s national reputation in America. Though the people of Denver had always loved him, his national stock was somewhat lower. Early in his career in Denver a local paper, the Rocky Mountain News, had published an expose about Smith’s wife and children. In 1885 he had met a girl named Mary Eva Noonan, who was singing on the stage at the Palace Theater. The two had three children, but Smith had kept her obscured and separated from his criminal life. When the story came out she was ostracized by her neighbours. Soapy’s response was to put her on the next train to St Louis, both for social and safety reasons. His enemies wouldn’t have hesitated to come at him through his family, which was why he’d tried to keep her out of his limelight. His second response was to put John Arkins, editor of the Rocky Mountain News, in hospital. Soapy fractured his skull when he attacked him with a weighted cane. The editor recovered, but after that he ensured every story that painted Smith in a negative light went on the national wire, while every story that might have made him look good was buried. The result was that across the USA, “Soapy Smith” was a byword for criminality. And even in Mexico, the name followed him.

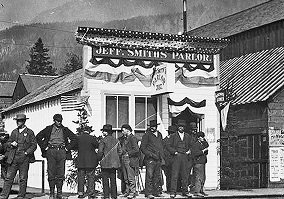

In 1897 a new opportunity opened up for Soapy. Gold was found in Alaska, sparking the Klondike Gold Rush. He immediately moved to the state, and set up shop along the mining trail in the town of Skagway. Local committees tried to move him on, but they had little teeth to do so. Soapy continued his tactic of ingratiating himself to the local community, and while he was perfectly happy to impoverish the well off travellers he did set up soup kitchens and shelters for those who found themselves truly destitute. He also contributed enough funds to hire two watchmen to patrol the residential areas to prevent burglaries. Soapy was, when it didn’t inconvenience him, a great believer in the rule of law. It made for a useful shield, for those able to think beyond it. Of course, not everyone saw it that way. Local vigilance committees, looking to impose justice on the remote frontier, constantly tried to get rid of Soapy. The most notable simply called themselves “101”, and they combined a major public campaign with an implicit threat of violence to try and unseat Soapy Smith. [4] They might even have managed it, if the USS Maine hadn’t exploded on February 15th, 1898.

Nobody knows exactly why the Maine exploded, but in the end the more important question was “where”. The Maine was parked in Havana harbour, in unspoken support of the rebels fighting for Cuban independence. Everyone was convinced, despite denials and a lack of evidence, that it had been destroyed by Spanish saboteurs to keep the US from interfering. If so, it had the opposite response. Instead it provoked a war between America and Spain, one that Soapy Smith was quick to seize on. Dusting off his old title of Colonel Smith he persuaded the US War Department to give him official permission to set up a volunteer militia to defend Alaska should the Spanish see it as a strategic target. The net result was that Soapy controlled an armed group of over 300 men and held an important official position in the community. In Skagway’s 4th of July parade he marched at the head of his company, seemingly unassailable. Four days later it would all come crumbling down.

The fleecing of John Stewart must have seemed like just business as usual for Soapy’s operation. He returned from the gold fields with a bag of nuggets, worth about three thousand dollars (or about twenty-five times that in today’s money). He hid the gold in his hotel room, but two members of the Smith gang he “befriended” persuaded him it would be safer in the bank. While they escorted him across town, they managed to persuade him to join a card game. Stewart tried to leave the game, claiming (probably correctly) it was crooked. At that point the gang just grabbed his gold and ran for it. Stewart tried to complain to the local deputy marshal but was fobbed off. He took to the taverns loudly airing his grievances, and it didn’t take long for the members of 101 to hear of it. They decided to hold a meeting to discuss the matter the next day.

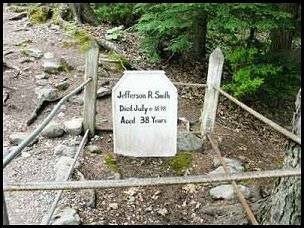

On the evening of July 8th the 101 and various other vigilance groups held a meeting in a warehouse on the docks to discuss the matter. Soapy was drunk, and when he received a tipoff that they were about to take the fight to him, he decided that he wanted to horn in on the discussion. He and several gang members headed down to the wharf. There Soapy tried to get past the guards, and got into a heated argument with Frank Reid, a member of “101”. Both men were armed, and the matter soon ended in gunfire. Who fired first is debatable, and some reports have it that another one of the guards (named Jesse Murphy) intervened and fired the final shot with Soapy’s own rifle. In the end, the result was that Frank was fatally wounded, and that Soapy Smith was dead.

The official story was that Frank and Soapy had killed each other, and Jesse was left out of it. The work of John Arkins ensured that nationally the death of Soapy Smith was seen as a victory for law and order. Though Frank Reid had at best a somewhat chequered reputation, in death he was lionised as a hero. He received a huge public funeral, and his gravestone’s epitaph read:

He gave his life for the honor of Skagway.

The end result probably was a victory for law and order. John Stewart got his gold back, and the three men who had stolen it went to jail. The White Pass & Yukon did get to build their railway, though ironically rather than destroy Skagway it wound up saving it. By the time it was completed in 1900 the gold rush had ended, but Skagway was in the position of being a deep water port with a railroad to the interior of the state. It gained the nickname of “Gateway to the Klondike”, and nowadays it survives on the tourist trade, especially cruise ships that pass by. A key part of that tourist trade is the legend of Soapy Smith, and a wake is held annually to honour his memory. Soapy’s reputation has recovered enormously in the last century, mostly during the 1950s. The contrast between stories of Soapy Smith’s heroic banditry and the bloody gang violence that had filled the US news since the day of Prohibition helped to polish his halo, and turn him into an American version of Robin Hood. Soapy Smith was no angel. He ruined lives and cracked skulls with no regret. But he stood by his friends, and he stuck to his code, and he died on his feet defending what was his. There are worse reasons to make a man into a hero.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] And serves them right. The USA was actually pretty radical on freeing slaves, and unlike the UK most former slave owners received no compensation (the only exception being in the District of Columbia, where the slaves were freed during the Civil War and the compensation was intended to stop the locals defecting to the Confederate side).

[2] Soapy would have ruled Las Vegas if he’d been born sixty years later.

[3] The court ruled that Governor Waite had been within his rights to dismiss the two commissioners, but not to send in the militia to enforce it. He didn’t have a chance to follow up and dismiss them through conventional channels before the furore caused him to lose the next election.

[4] Some historians see “101” as a front for the White Pass & Yukon railway company, who wanted to build a station right at the docks to allow miners to head straight to and from the gold fields. This was opposed by Skagway businesses, lead by Soapy, who saw this as an existential threat to their livelihoods.