‘Fashion with an Irish Brogue’: The Life and Legacy of Sybil Connolly

It was October 1953 on a flight bound for Texas from New York. Carmel Snow, then the editor of Harpers Bazaar was sitting with her cousin, Veronica Freeman. Next to them was a nervous young woman in her early thirties named Sybil Connolly.

A fashion designer, who grew up in Waterford, Connolly had just recently found success in New York, and as a result, her work was to be shown in the southern state. Her future was enormously promising, there was no question there, but she was still coming to terms with the sudden exposure. Studying the price lists for her collection, the innocence of Connolly surfaced when she expressed deep shock at the numbers. ‘They were double the prices in New York’, Freeman recalled.

‘My dear’, replied Snow coolly, ‘these are the prices for Texans. You have to do this in Texas; if you don’t, they think that they’re not good quality.’

For the Dalkey-born Snow, there was nothing extraordinary here. What was startling in the eyes Sybil was logical business to Snow. A veteran of the trade, there was no better mentor for Connolly than the woman once described as a ‘revolution in a pillbox hat’ who transformed Bazaar into a magazine ‘for well dressed women with well dressed minds’. Ireland had long been considered a country without fashion. That was of course, until Carmel Snow entered the business, and her discovery of Connolly helped insure such notions faded into obscurity.

Born in Swansea on January 4th 1921 to a Welsh mother and Irish father, Sybil Connolly was brought up in county Waterford. During 1938, at the age of seventeen, she went to London to learn dressmaking at Bradley’s, a company owned by two Irish brothers whose credits included dressmaking for the royal family.

In 1940, however, with the outbreak of the Second World War, all Bradley apprentices were sent home. Aged twenty upon her return, Sybil moved to Dublin and began working for Jack Clarke.

Ireland’s foremost fashion retailer, Clarke’s Richard and Alan department store on Grafton Street was one of Dublin’s popular retail outlets. Before the Second World War, Clarke had been a substantial employer and an astute business man. By opening the retail unit on Grafton Street, named for his sons Richard and Alan, he endeavoured to keep his wealthier clientele in touch with the latest fashion trends. Employing an in-house fashion designer, a French Canadian named Gaston Mallet, he also took on board Connolly, who acted as his workroom manager and company director at the age of twenty-two.

In 1952, Mallet left the employment of Jack Clarke abruptly. So Clarke, having encouraged Connolly early in her career requested she take over the designing of his 1953 Spring/Summer collection. Unlike Mallet who favoured French fabrics, Sybil spared no time in producing a collection which featured the use of native Irish fabrics and embellishments, most notably Irish linen.

The timing was impeccable.

A few months later, Snow, while travelling to Europe to view the import showings for the 1954 Autum/Winter collections, decided to make a detour to Ireland. There she ended up attending what was to become known in the press as ‘Irelands first fashion show’, and in the course of the evening, Connolly first caught her attention.

Carmel Snow may have had an affinity with the showcasing of Irish handicraft. Her father, Thomas White had been passionate about native handcrafts and had been honorary secretary of the Irish Industries Association. Whatever the reasons, Connolly’s vision charmed Snow. And so, she was presented an opportunity to launch herself in the United States during March of 1953 with the help of the Irish Exports board.

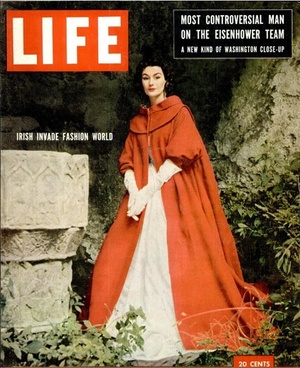

According to historian, Elizabeth McCrum, Sybil Connolly gave Irish fashion an international profile. After her US launch, Connolly’s career was well documented in newspaper columns of the 1950s. Blessed with opportunity and the ability to network successfully, she became beloved to the American press, who reported on her designs regularly. She would say years later that at the height of her career, seventy five per cent of what she produced was for the American market and that she in turn produced specifically for that market.

Reporting for the La Crosse Tribune of Wisconsin on October 1, 1953, Dorothy Rowe stated that within a six month period, Connolly had taken the fashion world by storm, describing Connolly as an ‘Irish Charmer’ and a ‘triumphant ambassador for the auld sod ‘. Sybil herself, in this interview said that in Ireland there was a perceived notion of American family life having been gleaned from Hollywood; the idea that divorces and multiple marriages were the norm. Going on to say that since being in America, she had discovered that the women of America are much better wives and mothers than in Ireland, she also added a little surprisingly, in Ireland even low income families cannot manage without at least one domestic servant.

In the same month, another headline from the Providence Journal commented ‘Eire’s Sybil Connolly, designs for town and country’. Penned by Madeline Corey, the subtitle stated that the collection was based on ‘native fabrics’ and that the clothing was suitable for both Eire and America. This initial collection showcased clothes that emphasised the ‘Irishness’ of the designer such as ‘Cosy evening’, a skirt made entirely of crios. These were the hand woven belts worn by the men of the Aran Islands. ‘First Love’ was a ball gown made of handkerchiefed linen and interwoven satin ribbon. One of the most iconic dresses of the first showing was ‘Pink ice’ a pale pink cocktail dress which used Carrickmacross lace made for the first time in a colour other than black, white or cream.[pullquote] ‘My dear, these are the prices for Texans. You have to do this in Texas; if you don’t, they think that they’re not good quality’ [/pullquote]

In February 1954, Jean Wiseman writing for the Aberdeen Press commented on her collection by saying that the ‘embroidered cambric [is] worked by Donegal cottagers [making] fairly –like evening gowns’. The ‘bainin’ jackets were described as being fashioned from traditional clothing worn by fishermen of Aran and the hats produced by Connolly, influenced by the thatch roofs of the cottages of Aran. According to Wiseman, Sybil Connolly, coming from the ‘land of colleens, clogs, shawls and striped petticoats’ was a vital part of the fashion world.

[arve url=”“]

In March 1955, Vogue published an article entitled: ‘The fashion, throughout the fashion world’, which opened with the observation that international fashion never quite ‘jells until Paris is heard from’. Discussing fashion hubs such as Paris, London and Italy, for the first time, Dublin was being included in the same context.

Perhaps, the article speculated, this addition could have been due to the ‘Irishwoman’ in Sybil Connolly, which had prompted her to set up a system different to that of any other couturier. At this point in her career, she was making clothing to order and copying the designs in her own workrooms before sending them to America. This fact was peculiar. To have had the designs copied in America would have been a more obviously lucrative option for the designer to consider. Yet, such was not her desired means of conducting business.

She wanted to keep employment in the Irish workroom, and in the early ‘50s, over fifty women were employed in their homes for knitting and crocheting. It was Margaret Cheyne who coined the phrase ‘Fashion with an Irish brogue’, praising Sybil Connolly’s for making such a courageous decision. This big break, Sybil herself referred to as her ‘wonderful chance’.

In January 1955, the Irish Times commended Sybil Connolly for her having made the fashion trade sit up and listen. Then, in August 1956, they noted that while London fashion houses were heavily criticised for a recent Venice fashion show, Ireland saw itself the recipient of high praise. The Rome Daily fashion editor wrote that a white handkerchiefed linen ball gown by Sybil Connolly was one of the best dresses shown. On the same date, the Irish Independent went with the headline on the same story ‘Irish gown led London’s best in Venice’.

By the mid 1950s Sybil Connolly’s career was at its peak, and as this came, she sought to experiment with her acclaimed vision. Produced a collection entitled ‘The Cossack Look’ in 1956, this collection of clothing showcased a distinctly Russian influence, but of course was made from native Irish fabrics. Newspapers outside of Ireland focused on the colours, which had basic tones of brown, gun metal grey and black which were offset by Hyacinth blue, winter white and pale lilac.

The Daily Telegraph, in July 1956, ran with the headline: ‘Cossack suits and Connemeara shawls – that’s Irish if you like!’ The Daily Mail, on the same date stated ‘Connolly goes all Russian – the Cossack look is so excitingly feminine!’ However, Irish newspapers, at this stage were beginning to talk about other aspects of her business. The Irish Independent noted that Connolly got her linen direct from the weavers. Describing her as one of Ireland’s ‘prime exporters’, on her they bestowed the honour of having breathed new life into traditional Irish products such as lace, tweed and linen.

This shift, however, was not free from criticism on the home front. The American market may have stood to applaud her for the ‘East of Moscow collection’, but on July 16 1956, the Irish Times’ ‘An Irishman’s Diary’ section labelled her unpatriotic for naming using names such as ‘Kismet’, ‘Cossack’ and ‘Vodka’ in the collection.

Still, in 1957, Irish media, by and large remained positive, classing her as one of Ireland’s ‘Fashion Big 3’, which included Irene Gilbert, and Raymond Kenna. By this time, she had not only made a very distinctive mark, but had also developed a strong voice. As mentioned before, she was adamant to keep employment in Ireland, but equally, saw it vital to create new employment. In the Donegal Democrat during August of 1956, Connolly was said to have paid a high tribute to the Donegal industry. She was in the northern county to open the Glencolumbkill Agricultural show, where she maintained that Donegal was playing a noble part in Irelands export drive. She said the following:

‘I feel that as long as we can show such beauty in design and texture as we do in our Irish cottage industries, we cannot ever be called a vanishing race’.

Speaking at an address to the Irish Association for Cultural Economic and Social Relations, in January 1957, she stated that every country should attempt to use its own particular assets.

By March of the same year, in relation to her fashion collections, Sybil Connolly had redeemed herself in the eyes of the Irish press with her presentation of ‘The Lady Lavery Look’. The Sunday Mirror stated that Connolly had revived the gracious beauty of Hazel Marlyn, the heroic Lady Lavery, using only materials and lace from Ireland. The evening dresses from this collection were described as story book party clothes. Soft blues dominate the colour scheme. It was also noted that 54 women worked on the crochet Irish lace.

Peaking here, the following years marked here gradual decline, which began after she moved into a salon on Merrion Square. With the emergence of the mini skirt in the 1960s, the era of the ball gown had passed, and although she would continue to design, future efforts would be on a smaller scale.

In the decades that followed, nevertheless, she sought new challenges by diversifying her brand, designing tableware for Tiffany and textiles for Brunswick and Fils, while also creating a design for Nicholas Mosse pottery. Editing books on interior design and gardens, finally, in 1995, she authored a book on Irish handcrafts, entitled Irish Hands: The Tradition of Beautiful Crafts. Then, on the 6th of May, 1998, she died in her Dublin home, leaving behind a legacy as a trailblazer for Irish women both in fashion and business, a visionary and no mere ‘little Dublin dressmaker’.