Benvenuto Cellini, Vicious Renaissance Sculptor

We don’t know as much about history as we like to think we do sometimes. For example, almost our entire knowledge of the druids of ancient Britain comes from the writings of the Romans who quite thoroughly suppressed them. How much of what they wrote is true, we cannot know. This works the other way round, however. Some people become more important to history simply because we know more about them. If Benvenuto Cellini hadn’t left an autobiography behind, one of great historical importance, he’d just be another obscure Renaissance artist. As it is, he’s a window into a fascinating world.

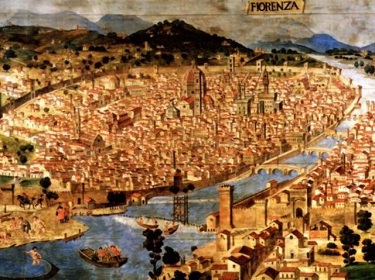

Benvenuto Cellini was born in the Italian city-state of Florence in 1500. His father Giovanni and his mother Elisabetta had difficulty having children. Though they had been married for twenty years when Benvenuto was born he was only their second child, and first son. It was for this reason that he was named Benvenuto, meaning “welcome”, as his father was both surprised and grateful to finally have a son. Giovanni was originally an engineer but had moved into both making and playing woodwind instruments after his marriage. He taught Benvenuto the flute from an early age, hoping that he would become a great musician. Benvenuto rebelled against this, though, and persuaded his father to let him study as a goldsmith as well.

Benvenuto had a brother two years younger than him named Giovanfrancesco, who was known for most of his life as Cecchino. Later in life he would become a soldier, and even at a young age he was prone to getting into fights. At the age of fourteen Cecchino fought a duel against a man of twenty and won, but he was immediately attacked by the man’s friends. He was injured by a thrown stone and would probably have gotten killed if Benvenuto had not been there to hold them off until the guards arrived. Duelling was illegal at the time, and so both the Cellinis and their opponents were sent into exile. It was far from the last time Benvenuto would be thrown out of his home city.

Benvenuto was allowed to return to the city when a friend of his father’s, Cardinal Giulio de Medici interceded on his behalf. The Cardinal then decided to send Benvenuto to Bologna to study music, and the young man went but spent most of his time studying goldsmithing instead. When he returned to the city he fell out with his father and moved to Pisa for a year, where he continued as a goldsmith. After he had returned to Florence and made his peace with his father he was working for a goldsmith in Florence when he met a sculptor named Piero Torrigiani. Piero saw his work and his designs and told Benvenuto that he was better suited to the sculptor’s trade. Piero tried to recruit Benvenuto to go to England to work on some sculpting there, but after Benvenuto found out that Piero was the man who had broken the great Michelangelo’s nose he decided that he hated him and refused to go.

Instead he remained in Florence where he began an affair with a young man named Francesco. Throughout his life Benvenuto was an unashamed bisexual who had a vast number of both male and female lovers, though the former often got him into trouble with the law. He and Francesco continued their affair for two year until 1519, when Benvenuto decided to go to Rome along with a friend of his to see what fortune they could find there. His friend went back to Florence quickly enough, but Benvenuto found that for a talented goldsmith like himself there was a lot of money to be made in the Eternal City. Nobody had more money than the Church, after all.

After two years in Rome Benvenuto returned to Florence, but his success at such a young age (he was 22 at the time) led some of the more established goldsmiths there to become jealous of him. His high opinion of himself probably didn’t help matters. It was during this stay in Florence when he was first prosecuted for homosexual activity, after the mother of his lover Domenico complained to the authorities. He was fined 12 staia (about 250 kilos) of flour. A few months later Benvenuto was back in the courts on a more serious charge. He was involved in a street brawl that led to him being put on probation, and then got into another while he was on the probation. He was forced to go on the run and fled back to Rome.

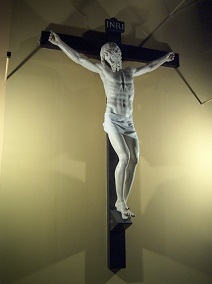

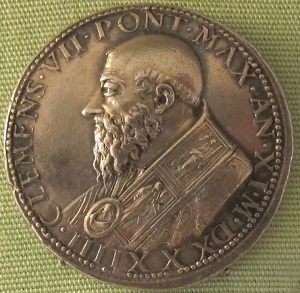

His fortunes in Rome took a sharp uptick in November when his old friend Cardinal Giulio de Medici was elected as Pope Clement VII. [1] In addition to church commissions he even wound up becoming one of the Pope’s court musicians after he was overheard playing his flute, something which his father was utterly delighted by. Benvenuto was less happy, as it meant he had less time to work on his commissions and had to deal with some angry customers. Still, it was one of the happiest periods of his life. He had good work, good favour and the occasional duel to fight with someone who disrespected Florence. He did have a brief brush with mortality when he came down with a plague that was sweeping through Rome, but on surviving it he threw himself into life with even more vigor. It would be a different story the next time plague affected his life.

The good times came to an end in 1527. Clement VII was not the best at international diplomacy and managed to get himself caught between France and the Holy Roman Empire. He aroused the ire of the Empire enough that Emperor Charles V sent another Charles, the Duke of Bourbon, down to chastise him with an army of Spanish and German mercenaries. Discipline in the Duke’s army was lax, and he had trouble maintaining order, but Rome was hardly set up to defend itself against a siege. The army was within the city within days, but it left Duke Charles dead on the ground outside. Benvenuto was defending the walls, as were all able-bodied men, and he later claimed to have fired the shot that killed the Duke. A tall tale, and in all honesty not something to boast of. Without the Duke to hold him back his men went wild in Rome in an outbreak of murder, rape, looting and vandalism that the city would not recover from for decades. A thousand captured Roman soldiers were executed after the battle, and between five and ten thousand civilians were murdered. The pope was again besieged in the Castel Sant’Angelo, his fortress in the heart of the city. Benvenuto was one of those who made it to the Castel, and was employed as an artilleryman in its defense. Eventually when it became clear that no relief was coming Pope Clement VII was forced to pay a massive ransom for his freedom, and spent the rest of his reign as a virtual puppet of the Holy Roman Empire. [2]

Thirty thousand refugees fled Rome, Benvenuto among them. In his own account his conduct as an artilleryman had led to him being offered the post of captain in a military company, though this may be an exaggeration. Regardless he returned to Florence, where his exile was temporarily lifted in recognition of his military service. If he had planned to become a professional soldier, then his father was able to persuade him to abandon the idea. His younger brother Cecchino was already a mercenary soldier, and one son in the military was enough for Giovanni. Instead he convinced Benvenuto to move to Mantua, where some of his friends from Rome had already settled. Benvenuto spent some time in Mantua but fell out with his noble patrons and returned to Florence. There he found that the plague had returned, and this time it had claimed the lives of both his father and his elder sister.

Benvenuto stayed in Florence for a while, as his brother and younger sister were also in the city and they wanted to spend some time together. He wanted to return to Rome, but this was complicated when his old patron Clement VII declared the Papal States at war with Florence. He was forced to conceal where he was going when he left the city, but he soon established himself in Rome once more. In 1529 his brother Cecchino was also working in Rome. When a friend of Cecchino’s was killed by a corporal in the Guards, Cecchino attacked them and killed the corporal but was wounded by a rifle-shot from one of the man’s fellow guards. He died of his wounds, and Benvenuto determined to take his revenge on the man who had killed him. Since the man had acted in self-defense he had to be discreet, but he eventually tracked him down and murdered him.

Benvenuto continued to craft pieces for the Pope and to create coin-stamping dies for the Roman mint. As a result of this he was made one of the Mazzieri, the mace-bearers who walked before the Pope on official occasions, though he was exempted from actually performing this duty. During these years he contracted “the French disease” as so many of his contemporaries did. His temper got him into trouble more than once, and on one occasion he had to flee the city when he nearly killed a friend by throwing a stone at him during an argument in the street. That same temper drove him to murder one of his rival goldsmiths shortly after the death of Clement VII. The confusion between Popes was a traditional time for settling such grudges and avoiding the consequences, and the new Pope was willing to issue a pardon in exchange for Benvenuto’s service. He did have to flee the city for a while to avoid the assassins who sought him in revenge for the murder, of course.

Eventually Benvenuto’s time in Rome came to an end in 1537. He did not find the new Pope as easy a master as the last one, and so he decided to spend some time in France to see what work he could find there. He didn’t like it and returned to Rome, but found that in his absence his enemies had framed him (according to him) for embezzling gems during his service to the Pope. He was arrested and held at the Pope’s pleasure, awaiting a trial that never came. When it became clear that he would not be released, Benvenuto managed to break out of prison by using his metalworking expertise to break the hinges of the door of his cell and escaping to the street on a rope made of bedsheets. He broke his leg when he fell from the rope, and though a friendly cardinal gave him sanctuary he was soon back in prison. Luckily for him the Cardinal of Ferrera was a firm ally of his and eventually persuaded the Pope to release him. After completing some work for the Cardinal, Benvenuto decided that Rome was no longer a healthy place for him and set off to France once more.

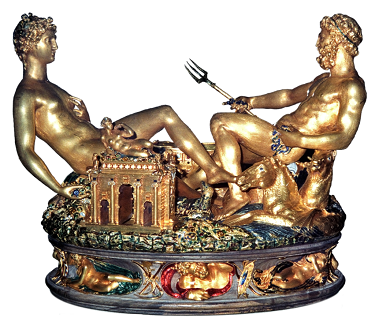

In France Benvenuto met King Francis and, after travelling around with his court for a while, was settled in Paris where he began to work once more. He made many piece of both sculpture and goldwork during his time in Paris, of with the most famous is the “Salieri”, also known as the “Cellini Salt Cellar”. This was a piece he had been planning for several years, but had not found a patron to finance. It is a table sculpture incorporating two small boxes for salt and pepper. The salt box is next to a reclining bearded male nude holding a trident, designed to look like Poseidon and representing the sea. The pepper box is next to a reclining female nude, who represents the earth. The piece is considered one of the finest surviving examples of art of this type that is available for public viewing. In 2003 it was famously stolen from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and a one million Euro reward was offered for information leading to its return. After it was recover it was insured for sixty million Euros.

During his time in Paris Benvenuto had several legal troubles. The most notorious of these was when he caught his mistress in bed with another man and kicked her out of his house. She sued him for “using her after the Italian fashion” (a euphemism for sodomy). This would have carried a potential death penalty in France at the time, and Benvenuto was tempted to flee the country. He decided to brazen it out in court however, and managed to win the case. He also feuded with Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly, the Duchess d’Etampes, who was the King’s chief mistress. He blamed her for a lot of his troubles with the lodgers in the property that he had bought as an investment. These men brought suit against him, and at first Benvenuto was willing to abide by the court’s decision. After he lost the first case, though, he attacked by night both of those who had sued him and severely wounded them both. The second man dropped his lawsuit.

As was common with most artists of the day, Benvenuto made his models into his mistresses as well. In 1544 one of these mistresses, a girl named Jeanne, gave birth to a daughter who was Benvenuto’s first child. Benvenuto gave her prestigious godparents and then handed her off to Jeanne’s sister to raise, along with enough money to support her and pay her dowry. After that he never saw her again. In part this was because he himself left Paris in 1545, never to return. This was the result of an argument with the King, who had originally hired him to produce a dozen large silver statues. By this point, five years into his commission, Benvenuto had completed one and almost finished another. In the true style of the Renaissance artist he tended to work where his inspiration took him, to the despair of those who hired him. Fearing that the King’s patience had worn thin and that he was at risk of being arrested once more, he managed to obtain leave to return home to Italy.

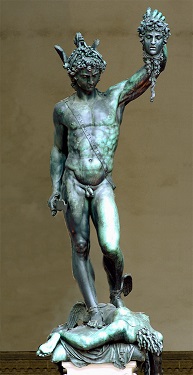

On his return to Florence Benvenuto was commissioned by Duke Cosimo de Medici to create a piece of sculpture to go in the Piazza della Signoria, the square at the heart of the city. Already in the Piazzi were some of the most famous statues of the time. The best known was Michelangelo’s “David”; but there was also a statue of Judith beheading Holofernes by Donatello and a statue of Hercules killing the monster Cacus by Bartolomeo Bandinelli. All of these showed a moment of triumph over evil, a victory for an underdog, and all were deeply symbolic of how Venice saw themselves. It was a signal honour to join their ranks, and one that shows the esteem Benvenuto was held in. He gave a great amount of thought to his sculpture, and as well as showing another triumph of an underdog his subject was also a wry jest on how his piece compared to the others. He was working in bronze while they were working in stone, and so he chose the beast famous for petrifying those it gazed on. A field of stone statues was the perfect place to put a Medusa, and in a sense he reduced the other works into mere props for his tableau.

Creating the sculpture was not without difficulty, though. Benvenuto’s brother in law died during the sculpting, and so he found himself suddenly supporting his sister and her six children. All through his life he had avoided such responsibility, and now he found himself the patriarch of a family. In addition Benvenuto developed a rivalry with Bandinelli (the sculptor of “Hercules and Casus”) based upon Benvenuto’s deep-seated admiration of Michelangelo. Originally the “Hercules” was to be his work, but it was taken and given to Bandinelli much to the disgust of Benvenuto and like-minded fans. For his part, Bandinelli suffered from an inferiority complex that drove him to hate the constant comparisons between his work and that of Michelangelo, and he soon grew to hate Benvenuto as well. Production on the statue was delayed due to the petty vengeances of Bandinelli, disrupting the flow of materials and labour that Benvenuto needed. The greatest difficulty came when Benvenuto finished creating the statue in wax, made a cast of clay around it, drew out the wax, and then set to pour his bronze in. While he slept his assistants let the temperature of the melting bronze drop too low, and it began to clot. Benvenuto was forced to first raise the heat much higher to counteract this, and then sacrifice all the pewter plates and cups he had in the house to adjust the alloy and remedy the changes made by overheating it. In the end the piece was a great success, and is considered one of Benvenuto Cellini’s crowning achievements as an artist.

The “Last Italian War” broke out in 1551. The various states of Italy were all part of the Holy Roman Empire, and the French sought to bring them into their nascent empire instead. Florence declared for the Holy Roman Empire, while nearby Siena declared for France. This led to a smaller war between the two powers, and Benvenuto’s service in Rome’s militia led to him being called on to help shore up the defenses of Florence. The war ended with Florence victorious, and Duke Cosimo of Florence became Grand Duke Cosimo of Tuscany, which replaced the old duchy with a new land that included both Siena and the island of Elba. It would remain one of the most prominent Italian states until the peninsula’s eventual unification.

Benvenuto stayed in Florence (with occasional visits to Rome and Venice, among other places) for the rest of his days. He continued his rivalry with Bandinelli, and on one occasion was convinced that he had been poisoned by the man’s confederates in order to undermine a competition they had for a piece of work. Perhaps it’s a sign of how much he’d mellowed in his old age that he didn’t set out to murder the man. In 1556 he was charged with homosexuality once again and had to pay a hefty fine, but his influence meant that he was not imprisoned but instead put under house arrest. While under this supervision in 1558 he began work on his autobiography, which eventually covered his life up until around 1562 or so. [3] Shortly after where that book leaves off he married a servant named Piera Parigi with whom he had five children. (By now his nieces had all grown up, and he may have missed being a family man.) He was a charter member of the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno, Florence’s artistic institute which was founded in 1563. He died in Florence in 1571, and was buried as befitted an artistic hero of the city.

Benvenuto Cellini’s autobiography was not published during his lifetime, and given the frank descriptions he gives of many of the important personages of the day that was probably by design. It was rediscovered in 1728 and published in Italy where it was an immediate success. Translated into English, German and French it shaped 18th century perception of 16th century Italy immeasurable. For example, the French author Alexandre Dumas wrote a novel based on Benvenuto’s time in France told from the perspective of his long-suffering assistant Ascanio. As a result Cellini became one of the “great names” of Renaissance art, as opposed to the obscure footnote he had been before that. In the end Benvenuto Cellini spent his life crafting great works of art in metal, but it was what he crafted on paper that would ensure his true immortality.

Images via wikimedia.

[1] Not to be mistaken for Antipope Clement VII, who was French.

[2] This indirectly led to the secession of the Church of England six years later. Since the first wife of Henry VIII, Catherine of Aragon, was the Emperor’s aunt the Pope was unable to grant the English king the annulment he wanted without displeasing his master.

[3] Some sources say that he finished writing it in 1562, however since he refers to events as late in 1566 it seems that he probably kept on working on it long past then and simply never wrote the later chapters.