Catherine Monvoisin and the Affair of the Poisons

Nothing makes history trickier to investigate than the whiff of scandal. Coverups and spin aren’t modern inventions, and when it makes every source you have unreliable then getting to the truth of the matter becomes all but impossible. So in today’s article all we can do is to report both the rumours and the official version; and let you draw your own conclusions about Madame Monvoisin and the Affair of the Poisons.

Catherine Monvoisin’s early days are sparsely documented, but we know she was born around 1640 and probably in Paris. Her maiden name was Catherine Deshayes, and her family were poor. From an early age she was fascinated with fortune-telling, learning palmistry at the age of nine. She had a talent for “cold reading”, the ability to read somebody’s cues as she told their fortune and convince them that she knew things that she could not normally have known.

Catherine was married in her teens to a jeweler named Antoine Monvoisin, and they would go on to have at least three children. Their eldest was a daughter named Marguerite who was born in 1658. Unfortunately Antoine’s business failed, and the family fell on hard times. In order to support them Catherine drew on her childhood interests and lifelong hobby, and began telling fortunes for money.

Catherine’s main form of fortune-telling was reading palms, sometimes called chiromancy. This was considered a “pagan superstition” by the Catholic Church, but many people at the time believed there was a science behind it. It provided the ideal ground for her to use her cold reading skills, and she soon became very successful. As a professional alias (and a pun on her name) she adopted the friendly title of “The Neighbour”; or in French La Voisin.

As with all such female fortunetellers, Catherine found that she was often visited by women with the problem of an illegitimate child on the way. Abortion was illegal in France at the time, of course, leaving women no option but to turn to shady characters like Catherine for assistance. Sometimes she gave them an abortion, sometimes she would deliver the child for them and then have it secretly adopted or otherwise dealt with. Either way, her utter discretion in these matters was probably a major factor in how she began to get more and more high-profile clients, including several from the nobility.

In the mid 1660s Catherine had become famous enough as a fortune teller that she was challenged by a priest over them. Rather than back down, Catherine chose to defend herself before the professors at the Sorbonne theological college. This college was well known for challenging “heretical” views (mostly Protestantism), but Catherine showed her mettle before them. She was an intelligent woman, far from what they had expected. Her spirited defence of the “science” behind her palm reading and her affirmation that any spiritual powers she possessed were gifts from God was enough to convince them to let her go. They were satisfied that she was not a heretic. But they were wrong.

By this time Catherine had graduating from telling fortunes to offering her clients a way to change those fortunes. This started out benignly enough; telling them to pray to a certain saint for assistance or similar. However as Catherine became more involved with the “occult community” of Paris (most notably “Adam Lesage”, a self-professed magician) this began to change. Another common problem among her visitors was the desire for someone to fall in love with them, and Catherine began selling magic charms and special powders to aid them in this. In 1667 she was asked to do this on a major scale. Someone wanted her to help them become the lover of the King.

The “someone” was Marquise Françoise-Athénaïs de Montespan, though it was her companion Claude des Oeillets (a former actress) who approached La Voisin. The king was Louis XIV, the “Sun King” who had risen from a child who was used as a puppet monarch to become the first truly absolute ruler in French history. He was one of the most powerful men in the world, and to become his mistress there was nothing Madame de Montespan wouldn’t do. Even if it meant literally selling her soul to Satan himself.

The first ceremony for Francoise took place in Catherine’s house. An abbot named Mariotte presided, with Lesage and Catherine assisting. After prayers to Satan, a drug was prepared and given to Madame de Montespan to use on the king. Whether it gave her the confidence she needed to win him or whether it did contain some aphrodisiac ingredients, in a short time Francoise was the king’s new mistress. This success boosted La Voisin to new heights. Soon she had escalated into producing full Black Masses for her clients in order to win them lovers and marriages, among other things.

The best account of one of these “masses” comes from 1673, when Madame de Montespan returned. The king’s affections were wavering, and she had decided a Satanic boost was needed. According to Étienne Guibourg, the priest who performed the ceremony, they laid a black cloth on an altar. Francoise then lay down on it, face up and completely naked. (According to some accounts she forced her maid Claude to do this instead.) As the priest intoned a blasphemous version of the liturgy, an infant was brought to the altar. The priest laid the chalice on the naked woman’s belly. Catherine then cut the infant’s throat and let it pour into the chalice, spilling out onto the woman’s body. She threw the body into a nearby furnace as the priest raised the chalice and completed the ritual.

Whether this was a genuine human sacrifice or just clever stage managing in a dark candle-lit room is hard to tell. Catherine’s daughter later testified that she bought pigeons for her mother and saw her cut their throats and collect the blood. She also said that the “altar” was simply a mattress on some chairs, with stools to the side for the candles. On the other hand at least one of the priests involved seems to have believed there was power involved and tried to use a Black Mass to prevent a friend’s mistress from conceiving. (It didn’t work.)

By the 1670s La Voisin had branched out into another line of work: poisoning. Her knowledge of chemistry, network of clients and reputation for discretion gave her the perfect alley for distribution of this type of substance. Soon she was at the centre of a network of distributors, a sisterhood of fortune tellers and backroom medics with a lethal sideline. Though their noble clients got the highest profile, they most commonly sold their poison to women trapped in abusive marriages who would find no relief from the legal system.

The poison they were distributing is unknown, but it’s likely to have been similar to one known as “Aqua Tofana”. This was a recipe that had been developed by an Italian woman named Giulia Tofana thirty or forty years earlier. The primary ingredient was arsenic, which was such a common poison that it was sometimes called “inheritance powder”. The gradual sickness it caused was perfect for allaying suspicions and for allowing the poisoner to manage the time of death. Other ingredients included belladonna and lead, resulting in a tasteless poison that looked like simple water and left the doctors of the time none the wiser.

Marital fidelity seems to have been in short supply in 17th century France. The king, of course, usually had multiple mistresses competing (sometimes murderously) for his affections. He treated them all with a shocking callousness, casting them aside at a whim and bedding anyone who caught his eye. (Claude, for example, had a daughter who was almost certainly the king’s child.) The marriage of the Monvoisins was equally unfaithful; Catherine had at least six lovers including her assistant Adam Lesage. Adam once tried to convince Catherine to poison her husband to get him out of the way, but Catherine decided against it.

It was the poisons that would lead to La Voisin’s downfall, through a path that began with a man who died in an accident in 1672. The dead man was Captain Godin de Sainte-Croix, an officer in the French army. In 1663 Godin had an affair with another man’s wife, Marie-Madeleine de Brinvilliers. Her father found out about the affair and had Godin imprisoned using a “lettre de cachet”. This was a French legal device where the king could order anyone imprisoned indefinitely without trial, something which nobles like Marie’s father could petition for him to do. Justice, under the French monarchy, was strictly optional when it came to punishment.

In prison Godin became friendly with an Italian alchemist named Exili. Exili taught the eager Godin about alchemy, including how it could be used to create poisons. When Godin was set free, he passed this knowledge on to Marie and soon they took their revenge on her father. His death was followed by that of her two brothers, which left her free to inherit the family fortune. (She later said that the real motive for killing her brothers was that they had sexually abused her when she was a child.) With her effectively separated from her husband, the two lovers were free to enjoy their lives together.

Unfortunately for Marie, Godin was paranoid. Afraid that she might poison him as well, he left a full sealed confession among his papers. It was labeled “to be opened if I die before Madame de Brinvilliers”. Since he died in debt his effects were seized by his creditors, who opened the confession and read it. Marie managed to escape arrest and fled to London, then moved to the Netherlands before settling in Belgium. There she was tricked, kidnapped and illegally extradited back to France for trial. In July of 1676 she was tortured into confessing, and on the strength of that confession she was executed.

Whether Marie was actually guilty or not is sometimes debated. The sole evidence against her was the word of a dead man and a confession tortured out of her. What is true is that her conviction, and the idea that three aristocrats had been murdered without anyone realising, was enough to set off a panic among the upper classes. When a fortune teller named Magdelaine de La Grange was arrested for forging a will, she tried to bargain for her freedom by claiming that she had information about crimes of “national importance”. Though she didn’t have any tangible information to share, her testimony was what began the official investigation that became known as la Chambre Ardente – the Burning Court. [1]

Over the next couple of years, the Court (led by Gabriel-Nicolas de la Reynie) swept up alchemists, fortune tellers and others on the fringes of society who could be suspected of using poison. One of these was Louis de Vanens, who was suspected of selling poison that was used to murder the Duke of Savoy (one of the highest noblemen in the land). Though they became convinced there was a secret organisation to these poison-sellers, they had no luck in cracking it open. Then in 1679 they hit the jackpot when they arrested a poisoner named Marie Bosse.

Marie was arrested after she got drunk at a party and started boasting that she had become so rich by selling poisons to the aristocracy that she would soon be able to retire. One of the guests informed on her to the police, who set up a sting to buy poison from her. Once they had verified the deadliness of what she sold them, they swooped in and arrested her. (Allegedly when they arrested her she was in the middle of incestual relations with her two sons and her daughter.)

Marie was tortured into a confession which gave up the entire organisation of poison sellers in Paris, and which place Catherine Monvoisin right in the centre of it. La Reynie hesitated to arrest her, as he knew that she was connected to some very powerful people at court. He finally arrested her in March of 1679. In doing so he may well have prevented her from carrying out the most high profile poisoning of her career: that of Louis XIV himself.

Madame de Montespan had always said that she would kill the king if he abandoned her, or so it was claimed later. (It’s worth noting that this plot is the sketchiest part of some very sketchy history, and it may be that none of this is true at all.) At the time it looked like he might be about to set her aside and replace her with a young girl named Angelique de Scorailles. (Angelique did die the following year, possibly due to complications from childbirth or pneumonia. Of course, rumours said she was poisoned.) The alleged plot of Catherine and her accomplices was to present a petition to the king which had been treated with a contact poison. Her initial attempt was foiled because there were too many other petitioners for the poisoned one to be presented directly to the king. She was allegedly on her way to plan a new attempt when she was arrested.

Initially Catherine tried to defend herself by claiming that Marie Bosse had made the accusations against her in order to save her own skin by denouncing a rival. (This was undercut in May of 1679, two months after Catherine was arrested, when Marie and her children were all executed.) Catherine’s maid Margot, who had also been arrested, warned the investigators that they were playing with fire. The arrest of Catherine Monvoisin, she said, would impact on people “at all levels of society”. That convinced La Reynie to tread carefully, though he was quick enough to scoop up all of Catherine’s associates. Then he started figuring out exactly what he had.

Though an authorisation was issued to torture Catherine for information, it never seems to have actually been used. Perhaps La Reynie was worried about what she might say; or he was aware of how unreliable information gained that way could be. Instead he took advantage of Catherine’s functional alcoholism and had his interrogators make sure she was permanently inebriated. It paid off; initially she stuck to her story that she had sent anyone trying to buy poison to Marie Bosse but soon she was naming names. The first people she named were minor nobles who received minor sentences; something which began leading people to denounce the court as a farce. In response Louis XIV declared in December of 1679 that the investigators should spare nobody, regardless of rank. It was a declaration he would regret.

Catherine Monvoisin went on trial in February of 1880. It was a very short trial, even given the amount of evidence against her. After the inevitable guilty verdict, a warrant was issued that she should be tortured to produce a confirmatory confession before the death sentence was carried out. However though the official records say that this was done, accounts at the time say that the order was ignored. The authorities were still doing their best to keep Madame de Montespan’s name out of these events, and had no wish to provoke an indiscreet confession.

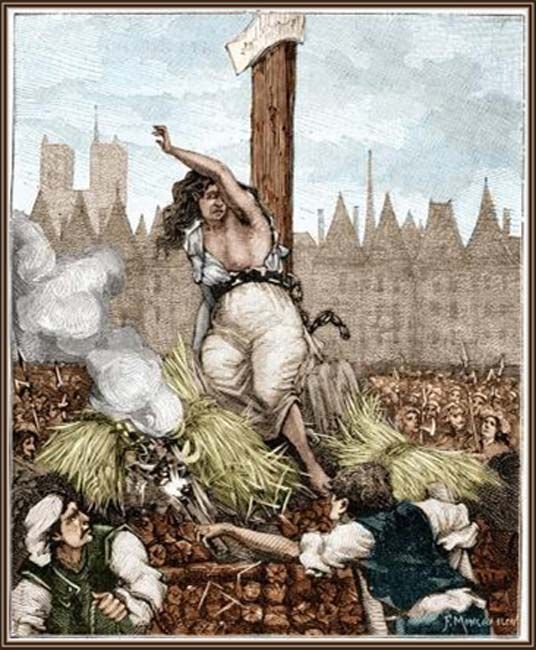

Catherine was executed less than a week after her trial, burned alive in the Place de Grève. She did not go quietly to meet her fate. The night before she persuaded her guards to let her drink her fill and eat a hearty last meal, and it’s possible that as she was dressed in white and taken to her execution she was still quite tipsy. A priest tried to persuade her to confess, but she violently repulsed him. At the execution ground she had to be dragged, fighting every step of the way, to the stake. As the fire was lit she did her best to kick the burning straw away from herself, but it was all in vain. Soon the fires flared up, and when it died down she was dead.

The death of Catherine did not bring an end to the investigation of the poisoning ring, of course. In fact it seems to have intensified it. In part this was due to her daughter Marguerite, who seems to have realised that she would have to work hard to avoid following her mother to the scaffold. She and her brothers (who were living with their father) had initially not been arrested, but shortly before her mother’s trial the authorities had swept them up. This might have been part of the attempt to wrap up the investigation. If so, it failed. The arrest of Marguerite was about to begin a new and even darker phase of the affair.

Marguerite’s confession soon began to paint a picture that was even darker than the Burning Court had expected. The tale of black masses and human sacrifices that unfolded shocked them, but it also seems to have convinced them that Marguerite had played no part in the affair. Those she named (Francoise Filastre, Adam Lesage and Etienne Guiborg among them) were soon confirming the story.

As soon as Madame de Montespan’s name entered the picture, matters took a different turn. It was one thing that she might have used magic to ensnare the king’s interest, but the idea that she had tried to have the Queen to be set aside and for her to marry the king was unthinkable. But she was the mother of recognised and legitimised royal children, and for that reason alone she could not be caught up in this. In addition she was far from the only noble implicated. Olympia Mancini, the head of the queen’s household and the most senior female non-Royal at court was the most notable of those implicated. With such explosive accusations being leveled, it soon became clear that Louis’ declaration of disregard for rank was just empty words.

Instead, the Poison Case Investigation became the Poison Case Coverup. The records of the trial were burned (though the interrogation records from the Bastille survived and allow historians to reconstruct the events). Those who could be safely executed on other charges (like Francoise Filastre) were put to death, but it was decided that none of the others could be allowed to go free. Instead Louis issued a great number of the infamous lettres de cachet. Anyone even slightly implicated was to be imprisoned for the rest of their lives.

That included Marguerite Monvoisin, even though the investigators concluded that she was innocent of wrongdoing. Minor details like that barely mattered in the court of the Sun King. She was imprisoned on the island of Belle-Île-en-Mer off the coast of Brittany, along with Margot the maidservant and Catherine Trianon among others. They were guarded only by women (to prevent them from seducing their jailers and escaping) but they were otherwise permitted to live under house arrest in the Palace Royal on the island. Catherine Trianon committed suicide in 1681, but the fate of the others (along with the men perpetually imprisoned, like Adam and Etienne) is unknown. When the king of France sought to make you disappear, you disappeared.

As for those he could not make disappear, the Affair of the Poisons still marked a permanent downturn in their fortunes. Francoise de Montespan fell from the king’s favour, of course, but he still had to pay visits to her in order to maintain the pretence of a relationship and to “disprove” the rumours. Ten years later she was finally sent to retire to a convent, though her children were all given marriages and dowries suitable for royal princesses. Several other nobles, such as Olympia Mancini, were forced to flee the country. Her son Eugene was rejected from the French army because of this; he emigrated to Austria where he became possibly the single greatest general of 17th century Europe. In fact his military genius is often credited with preventing Louis XIV from achieving control of Europe in the decades that followed.

The Affair of the Poisons soon entered into popular French folklore as an example of the perfidy and perversity of the upper classes, along with their tendency to protect their own. Louis XIV sought to suppress the truth; but he didn’t realise that in doing so he was creating more fertile ground for the legend It became part of the history fueled a growing discontent among the people of France that would explode into revolution a century later. In the years since it has become the subject of novels, plays and films. La Voisin, it seems, refuses to be forgotten.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] The original Chambre Ardente was a nickname of the special court used at one time to prosecute heretics. Though it had been suspended over a century earlier, it was this legislation that was used to establish the new Burning Court.