Hans Fallada, German Author

Content warning: this column discusses suicide and episodes of suicidal ideation in the life of Hans Fallada.

Societies don’t go wrong all at once. Things get worse by degrees, and it can slowly creep up on you. You convince yourself that things are still basically the same as they’ve always been, and then you hear that people are being executed for peaceful protests while the regime are demanding you turn your talents to their use. Hans Fallada’s life under the Nazi regime was one of major compromises and minor defiance, all because like so many others he didn’t realise how bad things could (and would) get.

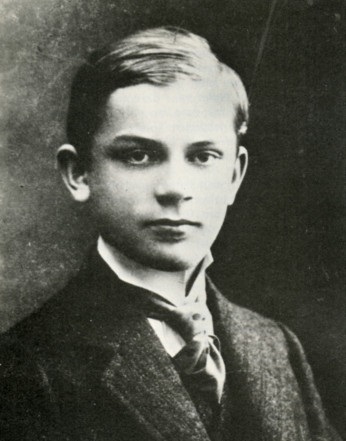

Though he became famous as Hans Fallada, that was only a pen name. His real name was Rudolf Wilhelm Friedrich Ditzen was born in 1893 in Greifswald, a small coastal city on the German coast of the Baltic Sea. His family left there for Berlin when he was six years old because his father Wilhelm had been promoted. Wilhelm was a judge, and in 1899 he was promoted to the Kammergericht, Prussia’s supreme court. Eight years later he was promoted to the Reichsgericht, the supreme court for the entire German Empire.

As a result his family were well off, though the constant moving had a poor effect on Rudolf. When they moved to Berlin in 1900 he was put into a school with a good reputation, but which turned out to be a haven for bullies. At the age of 12 he tried to run away, but his parents found out his plans before he did. He was moved to a different school, where he did much better. Then Wilhelm was promoted in 1908. This meant that the family moved to Leipzig, where Rudolf was involved in a fateful accident.

In April of 1909, while riding a bicycle, Rudolf collided with a horse-drawn cart. He was run over by the wheels of the cart and kicked in the face by the horse, and he was not expected to survive through the night. But he did survive, though it took him a long time to recover from his injuries. It might have been during the treatment for this injury that he was first introduced to morphine.

The following year Rudolf went on a trip to Holland with his Wandervogel group. This was a movement in Germany affiliated with, but separate from, the Boy Scouts. (It was outlawed in 1933 for competing with the Hitler Youth, but was refounded after the war and still exists today.) He enjoyed the trip very much, but while on it he caught typhoid. The disease was treated and he recovered from it, but it seems to have caused him to begin suffering from depression. He started drinking heavily, which led to arguments with his parents. And eventually he began contemplating suicide.

Rudolf’s first two suicide attempts were unsuccessful. He took poison (provided by a friend, Hanns von Necker), but it didn’t work. Then he tried to cut his throat, but he couldn’t go through with it. At the time Germany seemed to be facing an epidemic of suicide among young men. The macho military culture combined with a disdain for discussing mental issues were a potent mix that has blighted many times and places throughout history. Three young men in Rudolf’s class killed themselves around the end of 1910 and the beginning of 1911.

Rudolf’s own suicidal ideation was also fueled by guilt. He had been writing anonymous letters pestering a young woman he was obsessed with, but suspicion over them had fallen on a friend of his. So he planned to declare his guilt in a suicide note and then drown himself. He told the friend, who told his mother, who staged an intervention. Rudolf was restrained, and eventually was taken for the first time to a psychiatric clinic. It would not be the last.

Rudolf’s parents moved him to a new school in Rudolstadt, where his friend Hanns von Necker was studying. They didn’t know that Hanns had aided one of Rudolf’s previous attempts. In fact Rudolf wound up foiling one of Hanns’ suicide attempts by hiding his revolver. But when Rudolf found no recognition in his new school for his poetry and writing, he despaired and began listening to Hanns. Rudolf had an obsession with the story of Dorian Gray, and the idea of people being dominated by stronger personalities. He had tried to make himself into a dominating person, but now he felt himself being dominated. Hanns had an idea for how they could kill themselves without causing their family despair or dishonour. They could die in a duel.

They staged an argument where Rudolf “demanded satisfaction” from Hanns, setting the stage for their duel. Hanns had a revolver, while Rudolf borrowed a hunting rifle from his landlord. They headed out into the woods, where they took aim at each other and fired. They missed. Hanns had to show Rudolf how to reload his rifle, as he had never used one before. But despite that inexperience, in the next exchange of fire he managed to hit Hanns. Hanns begged Rudolf to finish him off, so he did. Then he used the last two bullets from the revolver on himself.

Rudolf was found staggering through the woods and taken to a hospital, where they found that a bullet had injured his lungs but missed his heart. Once again he wasn’t expected to survive through the night, and once again he defied that prediction. This time there were more consequences than the physical, though. Once it was clear that he was going to recover from his injuries, he was arrested for the murder of Hanns Dietrich von Necker.

Luckily for Rudolf, his father knew the law inside and out. He ensured that his son was placed in a hospital whose director was one of the great psychiatrists of the day, Professor Otto Binswanger. Professor Binswanger wrote a report on young Rudolf showing that he was not of sound mind at the time of the shooting, and so the murder charge was dropped. Instead he was committed to Tannenfeld Sanatorium.

Rudolf remained in the sanatorium until September of 1913, by which time his condition had much improved. He had learned how to deal with his depression, as best he could. By his doctor’s recommendation he got a job working s a supervisor on a farm, as it was thought that physical exercise would help. Though he still had ambitions of being a writer, nothing had come of this by 1914 when World War I came burning across Europe, changing everyone’s lives forever.

Rudolf had been declared unfit for conscription during his time in Tannenfeld, and though he tried to enlist he was first refused, then (after his father intervened) accepted but discharged after a month. When the farm work proved too harsh on his health he became a potato salesman, though he continued to try to become a writer and translator. His younger brother Ulrich did join the army, and four years at the front transformed the brave young man (who was the darling of the Ditzen family) into a nervous wreck. Ulrich died in August of 1918, less than three months from the end of the war.

Like many young Germans in the despairing days after the war, Rudolf became addicted to morphine. He was treated with it for stomach ulcers in the winter of 1918, and moved from that into “recreational” use. Around the same time he finally finished his first novel: Der junge Goedeschal, a semi-autobiographical story of troubled youth. The novel was not a success, but it did give Rudolf his pen name. He took it from the Brothers Grimm. Hans came from Hans im Glück, the story of a man who works for seven years and is well rewarded, but who is cheated out of his wages in a series of bad deals on his way home. Due to his simple nature he interprets all of this as good luck. Fallada came from The Goose Girl, where it is the name of a magical horse who speaks only the truth; and who is killed to try to stop him telling it. Both give insight into Rudolf’s self image. They combined to make the name that Rudolf would become famous under: “Hans Fallada”.

Fame would be a while coming, though. While he was working on the proofs for Goedeschal Rudolf suffered a nervous breakdown and returned to Tannenfeld. There he was treated for his morphine addiction. By the time he was discharged his book had been released. It hadn’t taken the world by storm, but it had done well enough that the publisher asked him to produce a second novel. Rudolf wrote an experimental novel called Die Kuh, der Schuh, dann du (”The Cow, the Shoe, then you”). It was rejected, but the publishers encouraged him to try again.

In 1923 Rudolf wrote Anton und Gerda. Though the heroes of the story are a schoolboy and a prostitute, the emotional content was largely based on an affair he had with a married sculptor named Annia Seyerlen. The ghost of Hanns von Necker also makes an appearance. It was Rudolf’s first critical success, though it wasn’t a matching popular success. His literary career was interrupted in 1923 when he was arrested for embezzlement. He had been stealing money from his employers to finance his morphine and cocaine habits. He was sentenced to six months in prison, but the sentence was deferred until the following year. In June of 1924 he reported to Greifswald prison.

Rudolf only spent five months in Greifswald before he was released for good behaviour, but it gives an important insight into his character. He kept a secret honest diary filled with defiance, but publicly he cooperated with the prison authorities and was promoted to trustee for betraying the escape plans of two other prisoners. He escaped from his imprisonment into writing, and emerged with a new novel called Im Blinzeln der großen Katze (”In A Wink Of A Big Cat’s Eye”). It was about a man awaiting trial for murder, a combination of his experiences as a teenager and his recent experience. He sold the manuscript to a publisher, but a combination of economic factors and changing public tastes meant it wasn’t released until after Hans Fallada was a famous name.

In 1925 Rudolf was working as the bookkeeper for an estate in Schlewswig-Holstein. It’s a sign of how turbulent Germany was at the time that a man with a conviction for embezzlement could be allowed back into such a position of trust. A trust he abused when he relapsed into his addictions on a business trip and stole all the money he had been trusted with. When he sobered up he realised that his history meant that he was likely to be committed to a mental hospital. He didn’t want that; he thought that he had a better chance of kicking his addictions and regaining his mental stability in a regular prison. So he surrendered to the authorities, made a confession to a bunch of additional fake embezzlement charges, and pleaded guilty at his trial. It worked, as he was sentenced to two years in a regular prison. But it also meant disgrace for his family, who now had a “hardened criminal” in their midst.

Rudolf was released in 1928 and moved to Hamburg, where he joined the Order of the Good Templar, a temperance movement. Alcohol, morphine and cocaine had been his downfall and he hoped to make a fresh start. The Order helped him to do that, and it also introduced him to Anna Issel (nicknamed “Suse”) who he married in 1929. In 1930 they had their first child, who was named Ulrich after Rudolf’s dead younger brother. In 1930 he got a job in Berlin working at a publishing company, which revitalised his own writing. In 1931 he released Bauern, Bonzen und Bomben (”Farmers, Bureaucrats and Bombs”) about rural corruption and revolution. It proved more political than intended. Rudolf’s own sympathies were with the left-wing SDP party, but the book was interpreted as supporting the rightwing momvements of the day. This led to success, but unnerved Rudolf.

Bauern, Bonzen und Bomben established “Hans Fallada” as a writer to watch out for, and helped Rudolf to get work writing reviews and short stories. But it was his following novel that pushed him to the next level. Kleiner Mann, was nun? (”Little Man, What Now?”) started out as a novel about unemployment but morphed into a story about how a weak man could be supported and sustained by a better woman. The protagonist is Johannes Pinneburg, a man who struggles to support his family in Germany’s economic crisis. But the hero is his wife Emma (known as Lämmchen, or “Lambkin”) who is the one that holds their family together through thick and thin. Lämmchen was based on Rudolf’s own wife Anna, of course. She was annoyed by this more than anything else; she thought that Lämmchen was an unrealistically idealised character. But unrealistic or not, the character struck a chord.

“Little Man” launched in the summer of 1932 and was an immediate success. Within four months it had sold over twenty thousand copies. Rudolf was astonished, as he thought it was worse than his previous novels. But he had hit exactly the right novel for exactly the right time. Between the sales, the film rights and the companies looking for translation rights, Rudolf was now a rich man. All of a sudden the lean years were over, and the future looked bright. Or it would have, if it hadn’t been 1932 in Germany.

In February of 1933 Germany’s parliament building, the Reichstag, was firebombed. Whether the fire was started by a Communist agitator (as the government claimed) or whether it was a “false flag” operation by the Nazi party, the result was the same. The recently sworn in Chancellor of the coalition government, Adolf Hitler, issued an emergency decree. Eighty-three Communist MPs were arrested. Almost all civil liberties, including freedom of speech and the right to privacy, were suspended. With their opposition suppressed the Nazis were able to manipulate the democratic process, and by the end of March fascism had conquered Germany. Adolf Hitler was now dictator, and the Nazi regime had begun.

The new regime literally came to Rudolf’s front door in April of 1933. He had just bought a house and the couple who he bought it from (who were Nazi party members) denounced him as a traitor so that they could repossess it. Though there was no evidence against him he was held without charge or legal representation for ten days. It was only thanks to his publisher hiring a lawyer on his behalf that he was released. Despite this the house (which he had paid for) was taken from him and given back to the couple he had bought it from. It was a stark lesson for the judge’s son in how little justice meant to the new regime.

In July of 1933 Rudolf’s wife Anna gave birth to twins, but one of them was injured during birth and only lived for a few hours. It was a blow, coming on top of the mounting stress as writers were arrested and publishers shut down by the Nazi party. Rudolf’s response was to try to move to the countryside and isolate himself from the new regime, to avoid political entanglements and to try to keep his own nose clean. However as a writer who required a public profile this was a plan that was always doomed to fail.

Rudolf’s first compromise with the new regime came with the release of a new edition of “Little Man” which, among other minor revisions, changed a character who was an unsympathetic bully from a Nazi party member into a professional footballer. His next novel (about the failings of the criminal justice system) included a foreword that these failings were now a thing of the past under the new regime. That was how he tried to insulate himself, but it failed. The Nazi press (by now the only press) attacked it as “written badly and without conscience”. Rudolf was going to respond to these attacks, but his publisher convinced him it would be suicidal to do so. With a new daughter (named Lore), Rudolf could not take that type of risk.

It was these attacks that first made Rudolf start to think about emigrating. Many writers were moving abroad, but Rudolf was reluctant. He loved his country life in northern Germany, and he convinced himself that he could live nowhere else. Germany seemed less fond of him. His next novel was acclaimed by the foreign press, but denounced as “not the type of book we need nowadays” by the Nazis. Stress over this contributed to a nervous breakdown in 1935 that put him into hospital. A few months after he was released he was told that he had been officially declared an “undesirable author”. His books weren’t banned, but he was not allowed to sell his work abroad or have it translated.

Further attacks made Rudolf decide that he had to emigrate. He put his farm up for sale, but selling it was more difficult than he had expected. In the meantime his main source of income was writing children’s books, where he could avoid any kind of relevance that might lead to trouble. One of his books was still banned in 1937 for mentioning the forbidden holiday of “Christmas”. In desperation Rudolf decided to return to the one novel of his that the Nazis had liked, and to write a new story set during the economic crisis of the 1920s.

Wolf Among Wolves is the story of a year in the life of Wolfgang Pagel and his girlfriend Petra Ledig, as they do their best to survive a country being ravaged by inflation. Since the novel tied into the Nazi narrative of the chaos endemic to democracy and the Weimar Republic, it went down a storm. Though it was far from being pro-Nazi, it still received the regime’s stamp of approval. And it got Rudolf one new and very influential fan: Nazi minister of propaganda, Joseph Goebbels.

As a result of this Rudolf was commissioned to write a novel that could be turned into a film about the life of a “typical German family” from 1914 to 1933. He tried to avoid turning this into the celebration of the Nazis that it was meant to be by ending the novel in 1928, but Goebbels insisted. The hero’s original “happy ending” (a simple country life) instead was rewritten to becoming a Nazi Party member. To add insult to injury, the film version never happened because a senior Nazi official decided he didn’t like Rudolf.

Over the last few months of 1938 as Germany began its path to war most of the Ditzen family’s friends and acquaintances began to leave Germany. Rudolf was going to be among them, and a ship to take his family secretly to England had already been arranged, but just before they were about to leave he changed his mind and decided to stay. It was his last chance to escape what Germany had become, and what it was about to become. War was descending on Europe.

Rudolf continued to try to avoid politics through writing comic novels and children’s stories, but the outbreak of the war meant an end to the English sales which had been a large part of his income. Paper rationing also affected his sales, while he found that country life was much less idyllic when jealous neighbours were able to file reports on them for tiny infractions. Under the stress his marriage suffered greatly. He did release the first volume of his memoirs around this time, though he admitted himself to friends that it was “full of lies”. The truth was a poor shield in the Third Reich.

The paper shortage in 1942 meant that publication of all books not directly tied to the war effort were suspended indefinitely, while the declaration of “total war” after the defeat at Stalingrad meant that even the 49 year old Rudolf could be drafted. Ironically around the same time he was under criminal investigation as a possible drug addict. Though this led to him being treated in a clinic for depression, the charges were dropped. He could not go without making some contribution to the war effort though, so he accepted an invitation to tour France and meet the troops there. It wasn’t really an invitation he could have refused.

As the war worsened for Germany, the farm at Carwitz became a refuge for their extended family. Anna’s two sisters and her niece along with Rudolf’s elderly mother all moved in. It was around this time that his wife discovered that he had been having an affair with a local woman. Though he had been unfaithful throughout their marriage, the fact that this time it had taken place under their own roof was too much. Encouraged by her relations (and by Rudolf’s mother), Anna applied for a divorce.

In 1944, with his publication contracts in tatters, Rudolf settled on a risky strategy. He agreed to write a novel for the German Propaganda Ministry about evil Jewish bankers, while hoping to be able to hold out until the inevitable end of the war and not to have to actually write it. He also began a relationship with Ulla Losch, the twenty-two year old widow of a soap magnate. He was still living in Carwitz at the time though, and in August of 1944 he got into an argument with his ex-wife that reached such heights the police were called. As a result of this he was sent somewhere he had once gone to prison to avoid: a mental asylum.

Mental asylums in Nazi Germany were not a good place to be. Euthanasia for “the incurable” was state policy, after all. Rudolf had the shield of Kutisker, the novel he was writing for the propaganda ministry. As a result he was provided with pens, paper, peace and quiet. But he didn’t work on Kutisker. Instead (using bad handwriting and overlapping letters to disguise what he was working on) he wrote Der Trinker. It was a semi-autobiographical novel about a successful businessman who descends into alcoholism and ruins his life. Arrested for the attempted murder of his wife, he commits suicide by deliberately infecting himself with tuberculosis. In addition to this novel, Rudolf wrote several short stories and a memoir of life in the Reich. It wasn’t a fully truthful account, as it did include a great deal of self-justification for his compromises with the regime. But it was frank enough to get him executed if he was caught.

He wasn’t caught. Instead he smuggled his manuscript out while he was on day release in the autumn of 1944. On the same trip he made an attempt to mend his bridges with Anna, who agreed to forgive him if he would stop his drinking. In order to reinforce this reconciliation, he legally assigned the ownership of the farm and house at Carwitz over to her. He was released in December, and after finalizing his reconciliation with his ex-wife he went to visit Ulla Losch to break off their relationship. It didn’t quite go as planned. Instead on the 29th of December he and Ulla announced their engagement. They were married on the 1st February 1945 and settled in Feldberg, near Carwitz.

In April of 1945 the Soviet army, conquering its way through Germany, rolled over Carwitz. Anna Ditzen was able to hide the 11-year old Lore from the soldiers, but she herself was raped and injured severely enough that she had to be hospitalised. This was a common fate for woman as the Russian soldiers arrived, especially those who lacked any form of protection. Ulla escaped that fate, whether through the protection of her riches or her new husband. Rudolf himself collaborated with the invaders, giving a speech to the locals that “The Soviets are our friends”. It’s unlikely that it was well-received, given what was going on. Perhaps as a result of giving this speech Rudolph was appointed as mayor of Feldberg by the Russians in May 1945.

It was a difficult job. Not only were Soviet troops still taking revenge on isolated farmsteads, but many of the locals were also resorting to theft as well. The stress took its toll on Rudolf, and he wound up taking morphine to cope with it. This was partly due to peer pressure from Ulla, who had always had a morphine problem. His health was ill-equipped to cope with this, and by August he had been admitted to hospital after a complete collapse. After he was released the couple abandoned Feldberg and headed to Berlin.

Rudolf and Ulla had not officially applied for residence in Berlin, because they thought they would be refused permission to move. As a result they had no ration cards, and since they were both still addicted to morphine times were very hard. In October Rudolf managed to contact Johannes Becher, a German writer who was working for the Soviets. He was keen to get Rudolf writing again and got him and Ulla ration cards. He was also the one who gave Rudolf a captured Gestapo file that would form the basis of Rudolf’s final novel, Jeder stirbt für sich allein (”Everyone dies alone”).

The file was about Otto and Elise Hampel, a middle-aged married couple. Elise’s brother had been killed fighting in France, which had crystallised their opposition to the war. They had never been a part of the “German Resistance”, but had acted on their own to try to speak out anonymously against the war. From 1940 until 1942 they had written two hundred postcards denouncing the war and the Nazi regime. Elise and Otto had dropped these into random mailboxes or left them in apartment stairways all around Berlin. They were eventually caught in 1942, and after they proudly admitted their actions they were executed by guillotine. [1]

Before he wrote Jeder stirbt für sich allein, Rudolf wrote Der Alpdruck (”The Nightmare”). This was a half-fictionalized memoir of the year after the end of the war. While he was writing it his second marriage hit stormy waters, partially because of Ulla’s inability to conceive children but mostly due to her morphine addiction and the debts she ran up to maintain it. Despite this distraction, he completed Jeder stirbt für sich allein in October. It was the first novel he had felt proud of since Wolf among Wolves.

Rudolf did not live to see the publication of his final novel. In December of 1946 he and Ulla were admitted to hospital together, the result of overdosing on sleeping pills. Rudolf’s health did not recover, and he died in February of 1947 of heart failure. He was originally buried in Pankow Cemetery in Berlin, but in 1981 his first wife Anna (by then 80 years old) succeeded in a campaign to have him reburied in Carwitz.

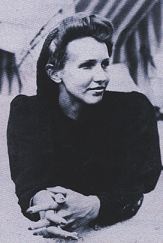

“Hans Fallada” remained popular in Germany after his death, on both sides of the Iron Curtain. However his complicated history meant that his works fell out of print outside of Germany, and in fact only two of his books (Der Trinker and a new translation of Little Man – What Now?) were published in English for the rest of the 20th century. One of the few academics outside Germany who studied his work was Professor Jenny Williams of UCD, whose biography of him (More Lives Than One) remains the premier English-language book on Hans Fallada. Her book was first published in 1998, but it was the 2009 publication of an English translation of Everyone Dies Alone that made Hans Fallada once again well known in the English-speaking world. It was a surprise best-seller, and last year it was made into a film with Emma Thompson and Brendan Gleeson in the lead roles. As a complex story of failed resistance and doomed protagonists, it seems fitting that it’s what Rudolf Ditzen (or rather, “Hans Fallada”), is remembered for.)

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] Sixteen thousand people were guillotined in Nazi Germany, around the same number of people as during the Terror phase of the French Revolution.