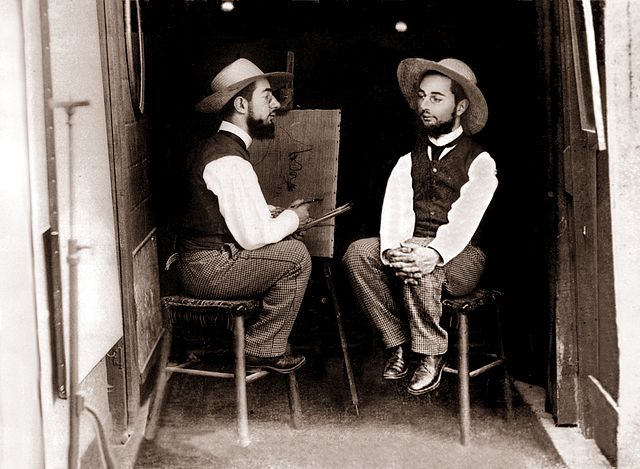

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Artist of Montmartre

One of the big problems with using paintings and other art pieces as a historical source is that most artists don’t depict reality as it is but rather reality as they wished it would be. Idealised and more attractive versions of historical figures stride through landscapes conveniently cleansed of any unwanted details. This is why Henri Toulouse-Lautrec is so fondly remembered as the “recorder of Montmartre”. His paintings showed real people living real lives, with all the ugliness that sometimes entailed. Henri’s own life left him fully conscious of the darkness reality could entail.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was born in November of 1864 in the town of Albi in southern France. As the “de” in his name would imply, he was of noble heritage. His father Alphonse was the Compte de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa; the heir to three noble French families dating back centuries. That nobility did not convey the same privileges it had a hundred years earlier, but it also didn’t carry the risk it had seventy years earlier. In the empire of Napoleon III (and in the Third Republic, which succeeded him in 1870) they were effectively just another well-off family, albeit one with a certain amount of social cachet. And some traditional obligations.

Henri’s mother Adele was also descended from the nobility. In fact she was descended from most of the same nobility as Alphonse, which was a problem. They were cousins, who had married in order to preserve a family fortune and noble heritage. (Alphonse’s brother also married Adele’s sister.) This close relationship was why Henri (ike several of his relatives) suffered from a rare genetic disorder, though it’s hard to tell exactly which one. He probably suffered from pycnodysostosis, which is often known as “Toulouse-Lautrec syndrome” because of this. It’s a disorder where the body lacks a key enzyme for bone development, resulting in (among other things) brittle and poorly developed leg bones.

Henri had a younger brother, but he died in 1868 at only a year old. This was apparently the final straw for his parents’ marriage, as they permanently separated afterwards. Divorce was out of the question, of course, as Adele was highly religious. She kept custody of Henri and moved to Paris, while his father was effectively absent from the boy’s life. He was a notably eccentric man, something else which Henri inherited. Henri was happy in Paris but Adele had some concerns about his health, and sent him back to Albi when he was eleven years old. That was where he suffered a serious accident.

The details of the accident are sketchy, but at the age of thirteen Henri broke his right femur. A year later he broke his left femur as well. At the time these two accidents were blamed for the fact that his legs stopped growing at this point, though if he did suffer from pycnodysostosis then they would have stopped growing regardless. The adult Henri was of average height sitting down, but was four feet and eight inches tall standing up. Naturally this had a serious impact on both his life and his outlook. Henri always considered himself an outcast, and he always felt most at home in the company of his fellow outcasts.

Whether or not the accidents were the cause of Henri’s height, they were definitely the genesis of his artistic career. Henri had always shown a talent for drawing but now unable to indulge in more athletic pursuits he was practically forced out of boredom to put in the work to make that talent blossom. His mother was delighted by this, especially since Henri was not a great student. Though he was originally enrolled in a college in Paris, after his accident he was tutored privately and passed his baccalaureate in 1881. After that his apprenticeship in art began.

His first tutor was a friend of his father named René Princeteau. René was from a noble family, like Henri, and like Henri he had something that set him apart. He had been born deaf. The two got on well and he taught Henri the basics of the trade, but Henri’s mother wanted to see her son become a fashionable society painter which René decidedly was not. So in 1882 he was taken out of René’s studio and enrolled him on the École des Beaux-Arts where he studied under the most noted portrait painter in Paris at the time, Léon Bonnat.

Léon Bonnat was much less sympathetic to Henri than René had been. He was very much an “Academy” painter, who believed that the rules should be followed above all else. He despised the Impressionists, who flouted those rules. This might have been why Henri came to be so heavily influenced by them. Despite the fact that the rancor between the two grew fierce, Henri did look back on this time fondly. Though Léon described his drawings as “atrocious”, Henri later said “the lashing of my former master pepped me up, and I didn’t spare myself.”

Léon left the school in 1883, and was replaced by Fernand Cormon. Nowadays Fernand is much better remembered as a teacher than a painter; as well as Henri he taught Vincent van Gogh, Émile Bernard and Eugène Boch among many other famous artists. At the time the paintings exhibited in the official annual exhibition of the Academie des Beaux-Arts (known simply as the Salon) were deeply conventional, and this was the type of painting that Fernand tried to impose on his pupils. Their later careers show how deeply unsuccessful he was at this, but his amiable disposition led him to encourage them in whatever path they chose.

It was while he was studying at the École des Beaux-Arts that Henri lost his virginity, something which had a profound impact on his life. While his fellow artists had numerous affairs with the models who posed in the studio, Henri was too self-conscious (and self-loathing) to even try to approach them. One of his friends there decided to try to coax him out of his shell, and persuaded a model named Marie Charlet to seduce him. This she did with gusto, boasting to her friends afterwards that “Portmanteau” (her nickname for Henri) was an excellent lover. This did a lot to enhance Henri’s reputation and his self-esteem, and it also awakened in him one of the appetites that would dominate his life.

His other appetite was for alcohol, which he came to rely on as a social crutch and as a way to deal with the constant poor treatment that he received for his height. At this time he confined himself mostly to beer, though this would change to harder drinks like absinthe later. It was probably due to these two appetites (and the disapproval of his very Catholic mother) that led Henri to move out and take up residence in the district of Paris that would become synonymous with the name Toulouse-Lautrec: Montmartre.

Out on the edge of the city (it had only officially been folded into the city in 1860) Montmartre’s inconvenient location for workers meant that the rents were cheap; which in turn drew artists, writers and other “bohemians” like flies. Their models also took up residence in the area, as did students and sex workers. This potent mix became the heart of the Belle Époque, France’s artistic golden age that began with the end of the war against Prussia in 1872 and was definitively ended 42 years later in the grim horror of the First World War.

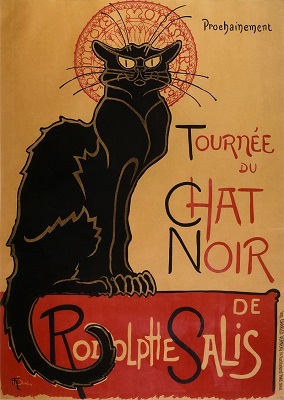

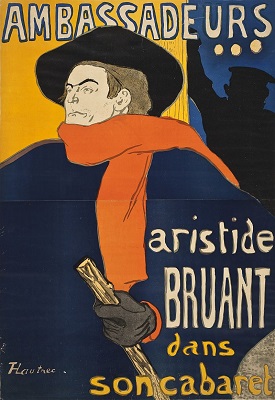

The heart of Montmarte in those years was Le Chat Noir, a nightclub that might have been the very first cabaret. The combination of tables where alcohol was served and a variety show meant that customers could converse among themselves or watch the shows as they wished, and the stage of Le Chat Noir soon became a place where dreams were realised. One of the stars of that stage was a comedian and singer named Aristide Bruant, while among the audience was Henri Toulouse-Lautrec. The two became good friends, and in fact Aristide may have been the first of Henri’s non-artist friends.

Another artist who frequented Le Chat Noir was Marie-Clementine Valadon, though at that time she was working primarily as an artist’s model. She had begun working as a model in 1880 aged fifteen, at that time using the name “Maria”. Prior to that she had trained as a circus acrobat, but an injury from a fall ended that career. She modeled for several artists over the next few years, the most famous of them being Renoir who painted her in Dance at Bougival. As was common she also slept with several of the men who painted her, which resulted in her becoming pregnant in 1883. Who the child’s father was is a matter of speculation, and though a painter named Miguel Utrillo claimed paternity he was almost certainly not the actual father. In any event the child was looked after by Maria’s mother, while she went back to work as a model.

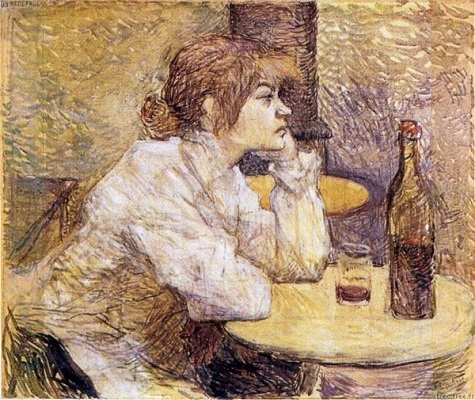

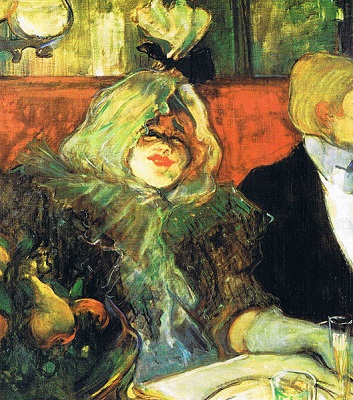

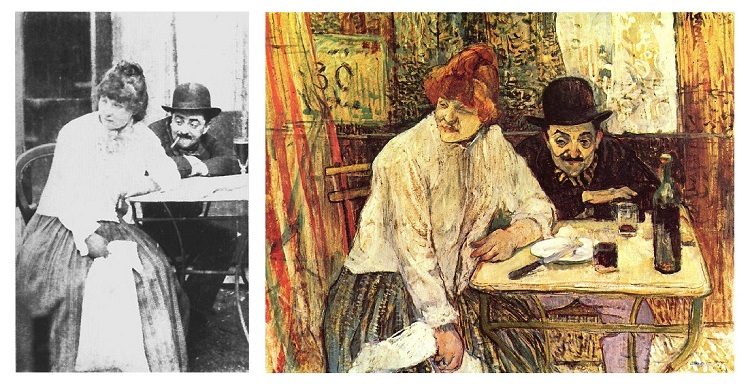

It was as a model that she first encountered Henri, shortly after he had completed his studies at the École des Beaux-Arts and begun working as an independent painter. That was in 1888. Maria became the model of some of Henri’s great paintings, including The Hangover: a painting of her sitting alone in a cafe grumpily drinking away the headache from the night before. She also became his lover, and then something more; she became his mistress. This was Henri’s first long-term relationship, one which was close enough that Maria opened up enough to show him something that she had never shown anyone: her own drawings. It was due to his encouragement that she started painting, eventually becoming one of the most famous female French painters of the fin de siecle era. She did so under the name “Suzanne Valadon”, which she adopted during her relationship with Henri. He nicknamed her Suzanne after the biblical Susannah (featured in the popular painting subject “Susannah and the Elders”) and she decided that she liked it better as a name than Maria.

Suzanne and Henri had an open relationship, something they both took advantage of. Henri slept with his other models, for example, one of whom gave him a “social disease” which was common in Paris at the time: syphilis. Popular legend has it that it was the model of Rosa La Rouge who gave him the disease, though this is complicated by the fact that we don’t know who that model actually was. Henri was impacted enough by the first phase of the disease that he left Paris for the winter to take a holiday for the sake of his health. Once it went into remission he returned, thinking (as so many did) that he was over the worst of the disease.

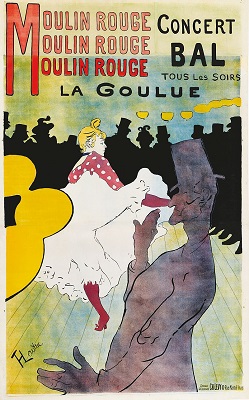

1889 was a pivotal year in Henri’s career. A highlight was exhibiting three paintings in the annual Salon of the Société des Artistes Indépendants, the indie alternative to the Academy. These helped to establish his niche as a documentary artist, one who recorded the real lives of the people of Montmartre in stark opposition to the idealised mythical scenes the Academy preferred. The other key event in 1889 was the opening of the most famous nightclub of Montmartre, and in fact maybe the most famous nightclub in history: the Moulin Rouge.

Henri was a regular at the Moulin Rouge right from the opening night. It was there that he invented a cocktail known as “the Earthquake”, a potent blend of cognac and absinthe that shows just how heavy a drinker he had become. It was also where he found new models and inspiration after he and Suzanne broke up in 1890. (There are rumours that she faked a suicide attempt in order to try and get him to marry her, though this might just be slander.) The most steadfast of those was Jane Avril, one of the dancers who popularised the Moulin Rouge’s most famous dance: the can-can. Another can-can dancer was Louise Weber (who used the stage name of La Goulue) and she was the subject of Henri’s venture into a new medium: the printed poster.

Henri was a huge fan of Japanese printing techniques, and he was very influenced by them in his own poster making. Unlike the detailed textures of his paintings, the posters use blocks of solid colour but still retain a dynamism and unique character. The most famous of these is his poster advertising Aristide Bruant’s appearance at the Ambassadeurs nightclub, showing his friend in his distinctive red scarf and black slouch hat. [1] But he painted many of them, which were pasted up around the city and gave his art a reach to the common people that salons and exhibitions couldn’t match.

Though Henri is best known for his paintings of Montmartre life, he did make one set of paintings in 1891 with a very different subject: surgery. His cousin Gabriel Tapie de Celeyran was a doctor who was studying surgery under Jules-Émile Péan, possibly the greatest surgeon in France at the time. He got permission for Henri to observe the great man at work, which inspired two paintings that had the trademark Toulouse-Lautrec realism. In fact it’s instructional to contast them with Henri Gervex’s painting of Péan. The Lautrec paintings show a man at work, intent on his trade as he operates on his covered patient. Gervex shows Péan orating to a class of students before he begins operating on a (naked and female) patient. One shows reality, the other demonstrates exactly what “art” of the 19th century usually entailed.

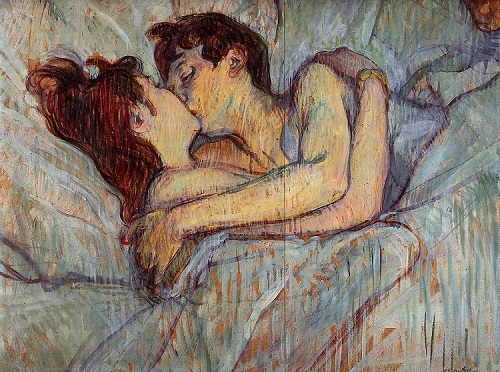

Despite his artistic success and his new friends, Henri’s disability still left him feeling an outcast. He was the subject of enough abuse and insults that it drove him deeper into depression and alcoholism. Henri sought solace with fellow outcasts, most notably in 1892 when he moved into a room in a brothel and took up residence with the prostitutes. This wasn’t a sex thing (or at least, not entirely a sex thing). Henri became friendly with them, and his paintings of the women living there combine a genuine affection with his usual realism. To most of society at the time, they were the lowest of the low, “fallen women”. Henri painted them as people.

Henri’s paintings are also notable for documenting another side of Montmartre that is often neglected by historians: lesbianism. France was one of the few countries in Europe that had decriminalised homosexuality in the 19th century, and Paris was one of the few cities where (discreet) same-sex activity was tolerated. [2] Though the residents of the brothels sold their favours to male clients, they often saved their romantic feelings for each other. Those weren’t the only lesbians that Henri knew well, either. His friendship with Jane Avril might have lasted for so long due to a lack of physicality between them; she was also a lesbian who had affairs with her fellow dancer May Milton and with the Irish singer May Belfort (both of whom Lautrec did posters for.) In fact Henri was one of the few men allowed to become a regular at La Souris, the most famous lesbian bar in Montmartre in the early 1890s.

1893 was another good year for Henri professionally. His friend Maurice Joyant organised a retrospective of his work that earned him critical accolades and recognition as one of France’s great painters. Even Edgar Degas, a deeply conservative man who strongly disapproved of Henri’s lifestyle, was forced to admit: “Well, Lautrec, it is clear you are one of us.” Henri also did covers for many of the literary magazines that were being published in Paris at the time, most notably La Revue Blanche which was published by his friends Alexander and Thaddeus Natanson. The fuel for the magazine was a salon hosted by Thaddeus’ wife Misia at which Henri was a regular. He enjoyed acting as barman for her guests, and became an expert at producing perfectly-layered cocktails for them. He was also one of many artists who painted her, including a poster-style drawing for the cover of “La Revue Blanche”.

Henri took a trip to London in 1895 to give moral support at the trial of a man he had met once before and admired, Oscar Wilde. Henri had played host to Oscar during a visit the writer had made to Paris. Despite being stereotypically portrayed as a “starving artist” Henri was one of the better-off people in Montmartre and was well-known as a generous host. He become almost as famous for his cooking as his painting; and his recipes were published by Maurice Joyant after his death as L’Art de la Cuisine. During that trip to London Henri also drew a poster for a British cycling company. He was a huge fan of cycling despite the fact that his disability made it impossible for him to cycle himself; and frequently attended and drew cycling races.

If 1893 was the pinnacle of Henri’s career, 1896 was when he began his steep decline. That was the year he published Elles, a book collecting his drawings of life in the brothel. (”Elles” is a French equivalent of “they” used when the group in question are entirely female.) The book was a commercial failure, largely because Henri’s drawings were almost deliberately unerotic. The French public had no interest in art that showed sex workers as being human. Meanwhile Henri’s prolific production of paintings and posters had slowed drastically as alcoholism began to take its toll on him. His friends did his best to help him cut down on his drinking; for example Thaddeus and Misia Natanson took him to stay in the countryside where they would have no drinks in the house. Unfortunately they didn’t realise that Henri was sneaking out to the local pub.

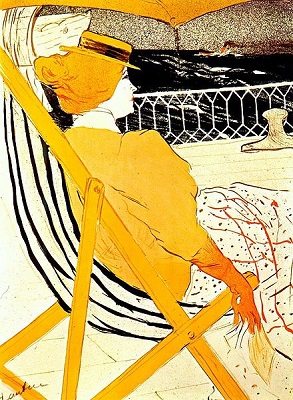

The effects of alcohol on Henri’s immune system allowed the syphilis he had caught years earlier to resume its ravages much sooner than would have usually been the case. With no effective treatment available the best his doctors could do was advise that he go on a cruise in the hope that the “change of air” might help him. During the cruise Henri drew a picture of one of his fellow passengers, a drawing now known as “the passenger in cabin 54”. Legend says that Henri became obsessed with her and stayed on the cruise long past his planned departure port in the hope of getting an introduction, but eventually left the cruise without meeting her properly.

Sadly Henri’s decline continued over the next few years. Whether due to alcoholism, wormwood poisoning (from drinking absinthe), or the neurological effects of the syphilis, he began to hallucinate. He became afraid of flies, and imagined great headless beasts trying to attack him. Things got so bad that a keeper was hired to stay with him so that he would not hurt himself. The keeper couldn’t stop the worst hurt he was doing to himself though: the continued drinking. Henri’s friends tried to keep him busy, and he did continue to paint and draw. All too often though his work during these years never progressed past sketch form.

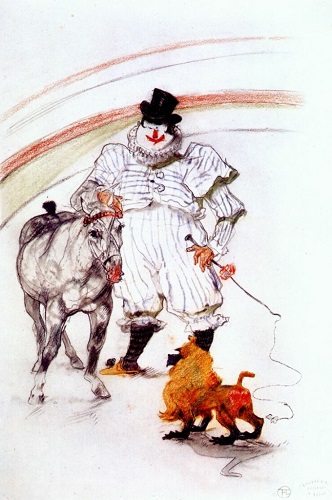

In 1899 Henri’s family decided to commit him to a sanitarium. They chose Folie Saint James, a former stately home (set among some famous landscaped gardens) that the original owner had been forced to sell in the financial collapse that preceded the French Revolution. It was a very high-class establishment, catering to the rich elite of Paris. Henri’s health soon began to improve, but soon he was well enough to begin desperately wanting to leave. After a few months he hit on the scheme of drawing to show how well his mental faculties had recovered. Among the works he produced in the hospital was a series of drawings set at a circus, demonstrating his memory and visualisation skills. The doctors were convinced and he was allowed to leave. He was warned however that if he began to drink again then he would collapse into an even worse state.

At first, things seemed to be going well. Henri was painting again, and even experimenting with new techniques and approaches to colour. His friends still worried though, and one thought that Henri “was forcing himself to resemble the old Lautrec.” Henri himself seems to have regarded it as inevitable that he would sooner or later relapse in alcoholism. Six months later, he did. His work began to fall off again, and his health also went into decline. His family cut down his allowance in the hope that this would make him stop drinking, but he stopped eating instead. Naturally this weakened him even further.

In March of 1901 Henri lost the use of his legs. This was a sign that the neurosyphilis was in full effect, and the end was near. A few months later he had a stroke. His mother (who he had been estranged from for some time) immediately took him into her home and put him under care. His health improved slightly, but then began to deteriorate. He died in September of 1901, aged only 36 years old. His last words were said when his father, who he had not seen in years, appeared at the deathbed. “Le vieux conf!” – “the old fool!”

Henri Toulouse-Lautrec’s work was heavily promoted by his mother after his death. Though she had never approved of it while he was alive, she seems to have regarded it as a way to honour his memory after his death. It was thanks to her that the Musée Toulouse-Lautrec was established in Albi where Henri was born. His work hasn’t always been “fashionable”, and some critics even describe the people he drew as “grotesque”. (Some even describe them as “caricatures”, revealing their own ignorance.) His own defence was simple:

I paint things as they are. I don’t comment. I record.

It’s thanks to that literal attitude, and to his unstinting sympathy with the forgotten people, that Henri’s paintings are not just works of art, but important historical records to help us understand the lives of those in Montmartre. Due to this Henri has become synonymous with and symbolic of the culture he drew, and has been portrayed multiple times in films set during the period. The most notable were the 1952 Moulin Rouge (which portrays the relationship between Henri and Marie Charlet, in highly fictionalised form); and the 2001 Moulin Rouge (where Henri is reduced to the role of comic relief.) Ironically the master of accurate portrayal became best known through inaccurate portrayals. But his true immortality came from his iconic art and posters, which gave us a window into the glorious past of the Golden Age of Montmartre.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] Henri’s posters of Aristide were the model for the costume worn by 1920s pulp hero The Shadow.

[2] This was the case for far longer than it should have been, and was why gay and lesbian culture in Europe (like Natalie Clifford Barney’s salon) continued to centre on the city well into the 20th century.