Hetty Green, the Witch of Wall Street

Hetty Green, America’s richest woman, was born as Henrietta Robinson in New Bedford, Massachusetts in 1834. Her father Edward owned the biggest whaling company in the city, and New Bedford was at the time the biggest whaling city in America. [1] His grandfather had gotten into the business early, but it was Edward who took the family to the top spot in the business. Her mother’s father, Gideon Howland, was also extremely well off. Since her mother was often ill and her father was usually absent on business, Hetty (who was an only child) was often left in Gideon’s care. His eyesight was failing in his old age, so from the age of six Hetty would read the financial papers to him and hear his comments on the state of the markets – an early education that saw her in good stead for the rest of her life. By the age of thirteen she was doing the accounts for her family, and though she was a poor student in most other aspects her skill with numbers was undoubted.

Hetty’s family were Quakers, and she was raised in that faith’s values of thrift and saving. Her formal education reinforced that, as she attended a boarding school for Quaker girls which catered to both rich and poor girls. The school essentially used the rich girls to subsidise the poor girls, and gave the same care to both in the hope of teaching the rich girls charity and humility. In Hetty’s case they simply taught her that she could get by on little, and thus be left with more.

Hetty was an attractive young woman, and her father was hopeful of getting her a good marriage, so he sent her to stay with a cousin in New York. He gave her a $1200 allowance to allow her to make an impression – but Hetty put $1000 in the bank and got her cousin to help her bargain hunt with the remaining $200. By all accounts she had a good time at the parties and balls of New York, but she failed to make the match her father had been hoping for. In part this was due to the flock of gold diggers her family wealth attracted, and Hetty decided then and there that she wouldn’t marry a man without wealth of his own.

Hetty moved back home, where she became involved in the family business and in acting as a nursemaid to her sick mother. In 1860 her mother died, leaving the bulk of her personal wealth to her husband and a relative pittance to Hetty. Allegedly Hetty considered challenging the will, but decided not to antagonise her father by doing so. This paid off when her mother’s sister Sylvia gave her a gift of twenty thousand dollars, which made her relatively well off. Still, Hetty was deeply alarmed when her father (still relatively young) had somewhat of a mid-life crisis after her mother’s death and moved to New York in 1861 to look for a new wife. She moved with him, in the hopes of derailing any romance. What she wasn’t expecting was to find a romance of her own.

Edward Henry Green was twelve years older than Hetty, but he did meet her criteria of having his own wealth. He came from a family in Vermont with money, and he’d increased his share of it by trading with the Philippines. He met Hetty through her father, as the two firms traded, and the pair struck up a friendship that soon deepened. It’s doubtful whether Hetty ever truly loved him, but she knew that society demanded that she marry and she wasn’t averse to the idea of children. Whether they told her father when they got engaged is unclear, but they hadn’t tied the knot by 1865 when he died. He had never remarried, and his fortune went entirely to Hetty – all five million dollars (in 1865 money) of it. Hetty was now one of the richest women in America.

It’s not surprising that Hetty made her prospective husband sign an agreement renouncing any interest in this fortune if they got married. What did raise eyebrows, though, was her reaction when her aunt Sylvia (the same one who had given her twenty thousand dollars five years earlier) passed away. Sylvia left half of her fortune to charity, and the other half to be held in a trust fund. The income from that trust fund (around sixty five thousand pounds a year) would go to Hetty, but she would not be able to touch the principal. On her death, that principal would then be distributed among the other descendants of Gideon Howland. Few people were surprised by the will – Hetty was definitely Sylvia’s favourite niece, but she’d have known that Sylvia wouldn’t need the money. In addition, leaving half of her fortune to charity was definitely a Quaker thing to do. Much less in the spirit of the faith were Hetty’s actions. In 1866 she sued to have the will set aside.

The official title of the case was “Robinson v Mandell”, with the principals being Hetty Robinson and Sylvia’s executor Thomas Mandell. However it soon gained a more informal title – the “Howland will forgery case”. The will in question was not the one that left half the fortune to charity, but an earlier one that left the entire estate to Hetty free and clear. Though this was an earlier will, the version Hetty presented had a codicil attached that said that this will would overrule any later wills. The legality of that was questionable at best, but it didn’t really matter. Mandell had decided it was a forgery and rejected it, and so Hetty had sued him.

The case didn’t make it to court until 1868, by which time Hetty Robinson had become Hetty Green – she and Edward were married in 1867. The case still bore her maiden name though, based on the original filing. It was notable for being one of the earliest cases to present evidence based on statistical analysis in court. After it had been demonstrated that the signature on the codicil was an exact duplicate of that on the main will, Mandell then called the mathematician Benjamin Peirce who showed the ways in which Sylvia’s signature normally varied meant the the chance of such a match was ridiculously remote.

The court ruled against Hetty, though it wasn’t Peirce’s evidence that was key but rather the fact that she was the sole witness to the signature on the codicil – since she was also the sole beneficiary, this made her witnessing, and the codicil, invalid. Ironically as soon as the case was ended Mandell immediately sent Hetty six hundred thousand dollars – the trust fund had done even better than expected in the previous three years, and with Sylvia’s final will in effect Hetty was entitled to that income. That might have led her cousins to try to have her indicted for forgery based on Peirce’s evidence. Rather than wait and see if they managed to do so, Edward and Hetty Green (who was now pregnant) moved to London.

Hetty’s first child, named Edward after his father (but always called “Ned”) was born in August of 1868. At the time the Greens were living in the Langham hotel, and they were still there three years later when her second child was born. This was a daughter, who without a trace of irony Hetty named Sylvia after her aunt. It was also during those years in London that Hetty made her first major coup.

Almost as soon as receiving her inheritance she had invested heavily in American “greenbacks” – bonds issued by the government to fund post-Civil War reconstruction. Many had balked at trusting the government at the time, but Hetty had bet that they would recover strongly – and it was a bet that added another million dollars to her fortune by the time the Greens returned to America in 1874. Those same investors who had avoided greenbacks had in the meantime invested heavily in railroad bonds, which crashed in 1872 causing three banks to fail. Hetty, of course, was then in a prime position to hover up as many of the crashed stocks as she could. (In the meantime, Edward had served as a director of three London banks – prestigious, but as always nowhere near Hetty’s level.)

As Hetty had alienated her own relatives, the couple decided to return to Edward’s family home in Bellow Falls, Vermont. There Hetty had an entirely new set of relatives to alienate. It was around this time that stories of her eccentricity and stinginess begin, though it’s hard to tell which are real and which are apocryphal. One story, for example, has it that young Ned injured his leg as a child (possibly during a period when he was in New York with Hetty). Rather than take him to the regular doctor, Hetty instead dressed them in old clothes and took them to the free clinic for the poor.

Alternate versions of the story have them recognised there and the doctor refusing to treat them for free, and even have Ned lose his leg after Hetty refuses to pay for treatment. Whether that’s true is hard to pin down, though the injury in question did cause him trouble for years and he did eventually have to have his leg amputated. By that time Hetty was infamous for her miserliness though, so the whole story might have been made up out of whole cloth. Another story is that when Edward’s mother died and Hetty’s house hosted the reception, she used the cheap glassware and not the fine stuff for fear the crowd would chip the expensive crystal – something that Edward was less than pleased about. Hetty was also on poor terms with the servants, who she accused of stealing, and the local shopkeepers, who she accused of cheating her. They in turn were less than complimentary to her.

The domestic tension between Edward and Hetty came to a head in 1885, when the financial house John J Cisco and Sons went bankrupt. Hetty was one of the firm’s investors, but it turned out that the single biggest debtor was actually Edward. He had persuaded the firm to loan him money based on the belief that Hetty would underwrite his debts, which she refused to do. From her point of view, their finances were completely separate. (By this time she had a net worth of around $27 million.) Without her bailing him out, Edward was forced to declare bankruptcy. He was deeply embarrassed by this, while Hetty saw his use of her name to shore himself up as a complete betrayal. She was also forced by the bank’s receivers to pay $422,000 to cover Edward’s debts, before they’d let her recover her own investments. The two Greens separated as a result, though they didn’t divorce.

For the next twenty five years, Hetty lived in a succession of rented apartments around New York and New Jersey – possibly due to a fear of assassination, which she was said to have inherited from her father. On one apartment in Hoboken, New Jersey she didn’t have her own name by the bell – instead it had the surname “Dewey”, after her dog. With the fall of Cisco she had transferred most of her assets to Chemical Bank (nowadays JP Morgan Chase), but she had deposits in many banks around New York and would carry her papers to their offices to do her business rather than rent an office of her own.

She still became well-known as the richest woman in the city, and in fact on three separate occasions she gave loans of over a million dollars to the New York municipality to bail it out of financial crisis. Her name became a byword for wealth. In an O. Henry short story, a young woman argues with a proposed amount she pay in rent with “I’m not Hetty, even if I do look green.”

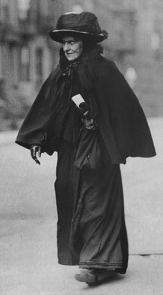

In 1898 Edward’s health began to fail, and Sylvia managed to persuade her mother to reconcile with him. She was by his side during his decline and eventual death in 1902. Following this she wore widow’s black for the rest of her life, and it was these clothes that earned her the nickname “the Witch of Wall Street”. The less charitable claimed that the real reason she wore black was that it required less cleaning than any other colour. Similar rumours claimed that she would only pay to have the hem of her dress cleaned, and that she would wear her clothes until they grew mouldy.

Sylvia and her mother were close, but it was Ned who was her planned successor. He was sent to Texas in 1893 to manage a railway company she had taken over there, which she thought could be a great success if managed properly. He passed this test with flying colours, and stayed in the state to manage her affairs in the south of the country. With the distance between them, he was able to get some measure of freedom and he became known as a much more lavish spender of money than his mother.

Ned was active in the state’s politics and was a friend and partner of William Madison MacDonald, a Republican politician and the state’s first black millionaire. He also became something of a ladies man, and later began a long term relationship with a prostitute named Mabel Harlow, who he met during a business engagement. Of course, he was well aware that Hetty would never allow him to marry her. Sylvia had a much more acceptable taste in partners though. In 1909 she married Matthew Astor Wilks, a member of the prestigious Astor family. This wasn’t until after Hetty had rejected several previous suitors though, and Hetty still made him sign a pre-nuptial agreement.

Hetty decided to bring Ned back to New York in 1910 to help her manage her affairs. He came (after accepting an honorary rank of Colonel from the state) and brought Mabel with him, though he kept her discreetly hidden from his mother. Hetty doubtless knew about her, of course, but the appearance of respectability was probably enough for her. For several years, for example, she had responded to stories of her miserliness by saying that she was simply following good Quaker principles of thrift. The fact that she signally failed to follow their principles of charity was beside the point.

One such story related to a hernia she suffered in her old age, as she only visited the doctor with it once it had progressed to the point where she could no longer walk. On examining her he found that she had secured the bulging protrusion by jamming a stick into her underwear. He told her that she would need surgery, and Hetty (who by this time was worth over a hundred million dollars) was horrified when he told her it would cost $150.

In 1911 at the age of 78 Hetty converted to the Episcopal faith that Edward had followed, so that she could be buried alongside him. Five years later she suffered a stroke, and after several more she died in July of 1916. It was later claimed that the final attack was brought on by an argument with a servant over the price of skimmed milk. Her fortune (which was somewhere between $100 and $200 million dollars) was equally divided between Sylvia and Ned.

Ned married Mabel, though perhaps in memory of his mother he did make her sign a pre-nuptial agreement. The pair had no children. Ned was much more lavish with his money after his mother’s death, and became known as one of the greatest coin and stamp collectors in America. He was enthusiastic about radio, air travel and motorcars – which he had specially adapted for his use due to his missing leg. In 1924 he paid to have the last surviving ship from Hetty’s father’s whaling fleet taken ashore and exhibited at his estate in Round Hill, Massachussets. This was also where he built his radio towers, and he financed one of the first radio stations in America to broadcast from there.

It was probably due to this spending that when Henry died in 1937 his inheritance of $75-100 million had been reduced to a “mere” $44 million. Due to his prenuptial the vast majority of this went to Sylvia, though Mabel got a half a million of it from the probate court. Sylvia’s husband had died in 1926 and she also had no children, so when she died in 1951 she left her fortune (with the exception of a relatively small bequest to a cousin) to charity. Hetty Green (who, four years later, the Guinness Book of Records would label “History’s Greatest Miser”) would not have approved. Perhaps that’s exactly why Sylvia did it – one final act of revenge against the Witch of Wall Street for ruling her life so harshly.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

This column was originally uploaded on 2nd May 2017.

[1] Nantucket had dominated the trade in earlier years, but as whaling ships grew bigger New Bedford’s larger harbor helped it overtake the smaller city.

[2] Round Hill was donated to MIT, who had been doing research there at Ned’s invitation.