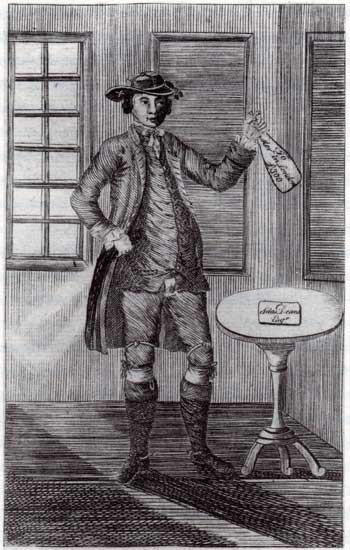

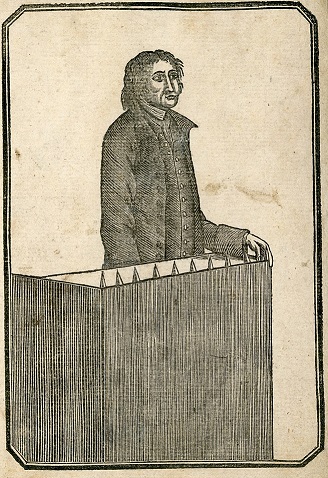

James Aitken, aka “John the Painter”, saboteur and arsonist

There are always those who see opportunity in the chaos of revolution, a chance for personal glory and historical immortality. Sometimes these men succeed, and are remembered as great heroes. Sometimes they succeed and are remembered as horrible monsters. Sometimes they fail and become a footnote in history. James Aitken, the man better known as “John the Painter”, was one of the failures.

James Aitken was born in Edinburgh in September of 1752. (His name might actually have been John, but it’s generally thought that it was originally James.) His father George was a blacksmith, or possibly a whitesmith (someone who worked with softer metals like tin). George and his wife Magdalen had twelve children, of which James was the eighth. When George died some time in the 1750s, Magdalen was left unable to support her family.

Luckily for James a man named George Heriot (court goldsmith to King James VI and I) had set up a charity in Edinburgh specifically to support boys like him. Construction began on “Heriot’s Hospital” (schools like this were called hospitals at the time) in 1628, but it was interrupted by the outbreak of the Civil War and the school being commandeered as a barracks. It finally opened its doors in 1659, and James would have been one of the first pupils to enroll.

Like may such schools, it combined a punishing study schedule with religious devotions designed to shape young minds towards living a good life, thought it’s fair to say that it didn’t really work so well in James’ case. The school did their best, providing him with apprenticeship in a trade: house painting. However this was a poor choice of job for James given that the house painting market was overfull and underworked. So he was forced to leave Edinburgh and seek his fortune elsewhere.

Our main source of information for this time in James’ life is a supposed autobiography published after his death. It’s not exactly a reliable source (having at least some provable inaccuracies), but it’s better than nothing. It claims that James (who it describes only as “a painter”) first tried to join the army as a commissioned officer (an unlikely choice for a poor man like him). When that failed, he moved to London and worked for a while before running himself into debt and being forced to flee. This was when he turned to crime.

The first criminal trade that James took up was highway robbery. He was successful in making some money from holding up and robbing carriages, but soon found that he was attracting a lot more attention than he’d have liked. Posters describing him and advertising for his capture led him to look into emigrating to America. Lacking the funds to travel there himself he signed himself into an indenture for twenty-four pounds to be paid in cash or service.

James’ indenture was sold to a man in Virginia, but he had no intention of staying there and working it off. Soon he was on the run up north through Maryland, and eventually made his way to New York via Philadelphia. He claims to have headed to Boston when he heard about the riots there and to have taken part in the Boston Tea Party, but this seems unlikely. Especially so because when he found out that Britain was going to send troops to the American colonies to pacify them, his first response was to get on a boat of there and back to England.

James landed in Liverpool in 1775 without a penny to his name, but he earned himself some traveling money by signing up with an army recruiter and then deserting shortly after he got his signing bonus. He made his way down to Birmingham where he got a painting job, but he found that “honest work” was no longer to his taste. So instead he robbed some shops, burgled some houses, robbed someone on the road and even pulled the army recruitment scam again. By the time he made it down to London he was comfortably flush and ready to hit the town.

James spent four months in London, where he “got into connexion with some women of the town”. In order to keep up this connection he committed several more robberies and burglaries around London. Eventually he began feeling the heat again and fled the city for Cambridge. After robbing his way through several other counties he joined up with an army regiment in Colchester, and this time he stayed in the ranks for a few months as a way of throwing off any pursuers his crimes might have put on his trail.

All of this comes from the supposed autobiography, of course. So does the charming detail that after he deserted that regiment and continued his rampage, his crimes included the rape of a shepherdess he met near Basingstoke. Whether that (or indeed any of the other details of his crimes) were added in order to titillate the reading public is impossible to tell.

According to that account was in Oxford that James had a conversation that changed the course of his life. He got into discussion about the American war, and found that the one point that everyone agreed on was that the British shipyards were utterly vital to the war effort. This gave James an idea. He saw a way to gain the glory and fame that he was sure that he deserved.

Whether that’s actually how it happened, or whether those self-serving motives were created to be accepted by an English audience, we don’t know. All we know for sure is that after visiting several of the shipyards (through finding work painting the buildings there) James was sure that he could cause serious damage by attacking them. The problem he faced was that getting passage to America in order to get backing for his scheme was basically impossible for him. Luckily there was somewhere far nearer that served as the main base of operations for American diplomacy in Europe – Paris.

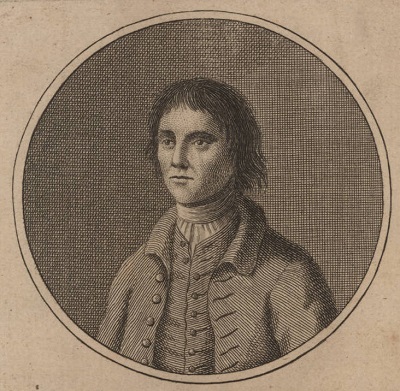

Silas Deane was the American-born son of a blacksmith who was able to win a scholarship to Yale and become a successful lawyer. Two marriages to two wealthy widows made him a man of means, leading to his election to the Connecticut House of Representatives in 1768. He was one of their delegates to the Continental Congress, which led to him being sent to Paris in March of 1776 to begin secret negotiations with the French. By the end of the year these negotiations would lead to France being the first European country to recognise independent America (though this was more down to their hostility with Britain than any love of the Americans). That success was still several months away when James Aitken arrived in Paris with his schemes and dreams of glory.

According to James’ “confession”, he spent some time tracking Silas before he approached him as he was passing across the Pont Neuf bridge. A meeting was arranged, where James claimed to own a plantation in America and that he was trying to get back to take part in the war but had been unable to get passage. He then gave his scheme of arson attacks on the dockyards, and produced some sketches that he had made of the yards. Silas was dubious, pointing out several flaws in the scheme (most notably that James would almost certainly be caught), and was also wary about blowback if it came out that America had backed this scheme. Still, he asked him to leave the plans and return the next morning.

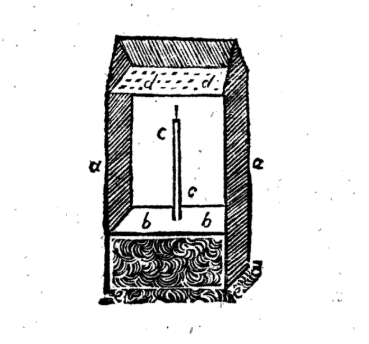

The next day James explained how he intended to avoid being caught setting the fires: by using a very simple form of firebomb, consisting of a candle in a tin box with the base filled with tinder. According to James, Silas was blown away by the ingenuity of this primitive device and promised him all the assistance that he could offer. This consisted of a small amount of money, a promise of a commission in the American army, and a contact in London.

How much of James’ account of this meeting is true is unclear. Silas later downplayed the whole thing as him humouring a man he thought was a crank. It might be true that he gave him the address of Edward Bancroft in London, as James visited Bancroft later. What Silas didn’t know is that Bancroft (one of his former pupils) had been “flipped” by the British intelligence service several months earlier. He would not be helping James.

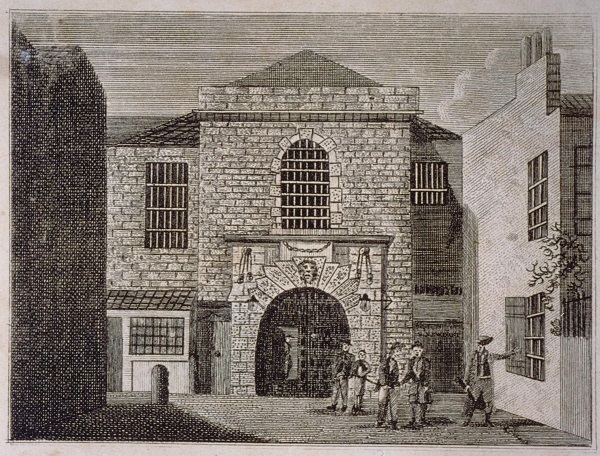

James arrived in the city of Portsmouth in December of 1776, with his firebombs and other gear in hand. He had picked up some pistols in London, in case of unexpected trouble. After securing lodgings (in a wooden house, which he planned to set ablaze as a distraction) he headed to the yards and set about preparing his fires. He set up one of his devices in the hemp storage barn, dousing the area around it with turpentine. He didn’t light it yet, though, as he hoped to set another fire somewhere else in the yard. By the time he’d finished setting that up, though, he realised he’d made a critical error: he’d stayed too late, and the gates were now locked.

Luckily for James he was able to attract somebody’s attention without attracting their suspicion, and they let him out of the compound. He made his way back to his lodgings, where he tried to set up a diversionary fire as he had planned. The landlady caught him in the act of testing his fuses (sheets of rolled paper coated in a mix of charcoal and gunpowder) and he was evicted from the premises. Deciding that discretion was a better course, he found a new guesthouse on the edge of town and headed back to the yard as soon as he could. He lit the candle on his firebomb (which, it later turned out, didn’t work) as well as a backup fire with a gunpowder fuse in the storeroom for ropes. Then he fled.

By now James was in a paranoid frenzy, worried that his original landlady would report him to the authorities. He ran out of the yard when he thought somebody recognised him, and decided to abandon the luggage he had left at his guesthouse. Instead he took a lift with a wagon headed to Petersfield, but when they stopped to water the horses he looked back and saw the flames at the docks. Immediately he abandoned the wagon and started running down the road. When night fell he tried to hail a passing carriage, but when it didn’t stop he fired one of his pistols at it out of temper. Eventually he did make his way to London, though. Truly a flawless getaway.

The ropehouse burned to the ground, destroying all of its contents, but thanks to the efforts of the fire brigade and a lucky wind the flames didn’t spread to any other buildings. It still burned for six hours, and a ship full of gunpowder in the port was put out to sea in case a stray spark sent it up. Such a sudden fire was suspicious, of course, but the initial investigation concluded that it was “accidental”. They would soon realise that was not the case.

Despite the fact that the damage to the port was nowhere near as much as he’d imagined, James was convinced he had struck a great blow and won a great victory. Buoyed by this, he went to see his contact in London: Edward Bancroft. (This is misspelled as “Bencroft” in James’ supposed memoir.) Bancroft was utterly horrified by this vagabond with tales of treachery, of course, and soon told him in no uncertain terms that he would have nothing to do with this scheme. Afraid that Bancroft would turn him in to the authorities, James left London in a hurry and headed to Plymouth.

James made his way to Plymouth via Bristol, where he rebuilt his finances by finding work as a painter (and then robbing his employer). With his purse refilled, he headed on. But things were not as easy as he had hoped. Plymouth Dock was and is one of the biggest naval bases in Britain, and a blow there might have had the results James hoped for. However precisely because of that security was far tighter than at Portsmouth, with the recent fire at Portsmouth leading to tight restrictions on entry to the dock. James managed to scale the wall with the aid of a rope ladder and grappling hook, but found the guard within as alert as the guards outside. So he was forced to move on, or rather back, to his alternative target: Bristol.

It was the middle of January 1777 when James arrived in Bristol, and this time he was determined to set a fire that would sweep the whole town. He targeted three ships in the harbour as well as a warehouse full of oil and combustible spirits. However only one of the ships was actually burned, while the owner of the warehouse realised there had been a break in and found the firebomb while checking to see if anything had been stolen. Annoyed by this James made several more attempts to set fires among the warehouses, with some success but not quite as much as he’d hoped. He did succeed in riling the town up enough that he had to move on, however.

Source

By now, unbeknownst to James, the firebomb he had placed in Portsmouth which had failed to ignite had been discovered. The British were aware they had saboteurs targeting their shipyards, though thy had no idea it was only a single man. Several other totally unrelated fires were put to his credit, leading to an assumption that a whole gang must be involved. The unsubtle exit James had made from Portsmouth meant that they had a description of him (where he was labeled “John the Painter”), and a reward of £2000 (an enormous sum of money for the time) was offered for his capture. The second firebomb being found in Bristol put the whole country on alert. Guards were set at every port, and strangers everywhere were under close watch.

James decided he had done enough, and decided to flee to Paris. He was short of funds, though, and committed one more burglary to get money to escape with. But he made the mistake of burgling a man named Lowe who had read that description. When his wife told him about someone she had seen casing the shop, he made the connection and immediately set out in pursuit. He ran James to ground in the town of Odiham with the aid of a jailer named Dalby. “John the Painter”’s reign of terror was over.

James admitted to the burglary he was charged with almost immediately. There was enough evidence against him that he could hardly do otherwise. Despite his guilty plea, the infamously stringent English legal system (known as the “Bloody Code”) meant that he was still going to receive a death sentence. It was a plain death sentence though, with the possibility of a pardon for “taking religion”. (This was professing to have found religion and recanted your sins, which led to escaping death for less serious crimes like theft. Doing this only worked once, and you were branded to stop you doing it again.) His crime of treason had no such escape route. It’s not surprising that he denied any connection to the harbour fires.

The authorities were eager to convict him. Being able to show that a single “lone lunatic” had been responsible for the crimes would be a major morale boost, since the public were convinced an entire gang of saboteurs were on the loose. They couldn’t torture a confession out of him as it would be inadmissible under English law (and public outrage wasn’t high enough to permit them to flout that law). In the end they did manage to convict him; thanks to an American painter named John Baldwin.

Baldwin was a “pensioner” of one of the Lords investigating the affair. Initially they hoped that Baldwin might recognise James from his time in America and be able to link him to some exploit over there, so they put them in a waiting room together. Neither had met before, but James struck up a conversation with him. They found some acquaintances in common, and James asked the former American to visit him in prison. Baldwin agreed.

With the encouragement of his patron, Baldwin became a regular visitor to James in prison. Over the course of the next week he managed to convince James of his revolutionary sympathies, and eventually James began to confide in him. First about his important friend Silas Deane, and then about the important mission Silas had entrusted to him. Soon the entire plot was exposed, and James was doomed.

The “confession” to Baldwin might have been legally dubious, but it contained enough verifiable details that they were able to use it to gather plenty of evidence against James. The luggage he had left in Portsmouth, for example, included his French passport along with other evidence. The craftsman who had made the canisters for his firebombs was soon identified, and was horrified to find out what they had been used for. All of this led to a final examination on February 24th where all of this evidence was put in front of James, and he could not dispute it. The next day he left London for trial at Winchester.

The only charge laid against James was burning the rope warehouse at this Portsmouth docks. This was why Dalby and Lowe never got their £2000 reward for capturing James. The government cheated them out of it by only prosecuting him for a crime that hadn’t been tied to the reward. They had more than enough evidence and witnesses to prove his guilt, and they made the trial into a show. James played to the crowd himself, and once it became clear that his one tactic (disputing Baldwin’s evidence) wouldn’t be enough he seems to have accepted his fate. He was found guilty after only a single day of trial.

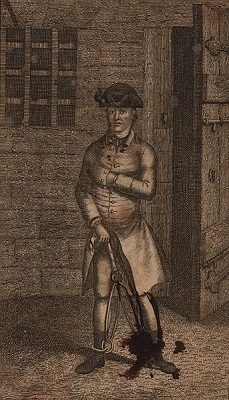

The night after his conviction, James gave his “confession”. This was his final chance at the fame he thought he deserved. Three days later, his sentence was carried out. He was carried on a cart past the ruins of the Portsmouth warehouse he had torched, and then taken to the gallows out side of town. Twenty thousand people had gathered to watch him die, though no record of his final speech remains. (The epilogue to his “confession” has him give an out-of-character repentance speech, but this seems dubious.) Then he was hanged from the mast of a ship, which had been taken and erected at the harbor gate as a makeshift gallows. It was so tall (over sixty-four feet) that he had to be lifted up to it by a pulley. After he died his corpse was put into a gibbet cage to be publicly displayed in the harbor for the next few years.

James failed to strike the blow against Britain that he hoped, but he did enter the history book, for a singular achievement. Though Guy Fawkes and his associates are generally held to be the first terrorists executed in Britain, they failed to carry out their objective. James’ attacks (especially his choice of civilian targets) definitely qualify as terrorism, and so he was possibly the first person to carry out a successful terror attack in the British Isles. His attacks led to a stiffening of public resolve against the American revolution, showing the ultimately self-defeating nature of this type of action. A legacy of futility, fitting for such an ultimately futile man.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.