Jane Toppan, Nurse and Serial Killer

From childhood we’re trained to trust members of the medical profession, so when that trust is turned on us it cuts deeply. The idea that these people who we rely on to save our lives might take it instead is a particular horror. And when that killing is done simply for the joy of killing, such as the murders committed by Jane Toppan? Then our terror knows no bounds. One newspaper described Jane as “worse than the political profligates of the medieval type, because they used poison against their enemies while she used it against her friends.” Nobody, no matter how close, was safe from “Jolly Jane”.

She was born as Honora Kelley in Boston in 1857 (or maybe 1854), the child of two Irish immigrants named Peter and Bridget. Nora (as she was known) was the youngest of at least three daughters, with her sister Delia being two years older and at least one other older sister named Nellie. Nora’s mother Bridget died of tuberculosis when she was only a few years old, leaving Peter to raise them on his own. Peter was a tailor; he was also an alcoholic who may have suffered from some form of mental illness. His abusive manner gave him the nickname of “Kelley the Crack”, which did not mean he was a fun party animal but rather that he was “cracked in the head”. It was probably a miserable childhood for Bridget, and by 1860 Peter’s abuse had become enough that she and Delia were taken away from him and put into care at the Boston Female Asylum. Their elder sister Nellie was old enough to make her own way, though apparently like her father she also suffered from mental illness and was eventually committed to an asylum. Urban legend has it that Peter suffered a psychotic break and tried to sew his own eyelids together, but his ultimate fate is unknown.

The Boston Female Asylum was an orphanage founded in 1799 by Hannah Stillman, wife of the Reverend Samuel Stillman. This was long before the idea of state care for children was invented, and so it was left to the charity of the generous to act as a social safety net. In fact, the BFA was the first charity ever established by women in Boston. Originally it had been set up to care for orphan girls between the ages of three and ten, but it soon expanded its mission to include children from “broken homes” like Nora and Delia. There was around a hundred girls in the BFA in 1860, though not all stayed until they reached the regulation ten years. Nora left the asylum in 1862 aged eight years old, fostered out as an indentured servant to a widow named Ann Toppan. As with Nellie and Peter, Delia’s fate is uncertain though the stories go that she wasn’t lucky enough to “find a place” like Nora and instead was driven to become a prostitute to survive.

Comparatively then Nora was “the lucky one” to have been placed with the Toppans. Old Ann Toppan didn’t like the Irish, an attitude which she did her best to instill in Nora. In fact she was the one who changed her name to the much less Gaelic-sounding “Jane”. She told everyone that “Jane” was Italian, a ruse which was helped by the fact that “Jane” was one of the “black Irish”. (This term refers to a recessive strain of dark hair and olive Mediterranean-style skin which pops up in many Irish families.) Jane was raised alongside Ann’s daughter Elizabeth, though she was never allowed to forget her place in the pecking order. Unlike many girls in similar situations she was never formally adopted into the Toppans, though Elizabeth at least does seem to have treated her well. Jane was sent to school by Ann, though she was not a very popular child. She was given to wild fanciful tales about her family, perhaps overcompensating for her lack of any real knowledge about them. Worse though, she was a snitch. She told tales on her classmates, which then lent her credence when she blamed them for her own misdeeds. And she spread vicious gossip about anyone who crossed her – or anyone popular she didn’t like. It’s not surprising that she made no real friends during her time at school.

On her 18th birthday Jane was freed from her indenture and given $50. She stayed with the Toppans though as a live-in servant for over a decade. Ann passed away some time in the 1870s, and a few years later Elizabeth married a deacon named Oramel Brigham. Jane herself was apparently engaged at one point, but her fiance left her for another woman. So she stayed on working for her foster-sister until 1885, when she finally decided that she needed to leave and make a life for herself. There were few professions open to women in those days, and most were menial at best. Jane thought better of herself than that, and so she decided to go for one of the most challenging, and the most rewarding, options available. In 1887 she applied to, and was accepted by, the nursing school at Cambridge Hospital in Boston.

In Jane’s previous life as a scholar she had been disruptive and gossipy, but she was well aware in retrospect that this had made her no friends. Nursing school was a chance to reinvent herself, and she did so well enough that she soon acquired the nickname of “Jolly Jane”. She preferred Jennie, though, and that’s what most people called her. The life of a trainee nurse was hard, working seven twelve-hour days a week with only two weeks of holiday a year. Compared to the life of a domestic servant though it was interesting and challenging in ways that Jennie could only have dreamed of. She bore it all without complaint, a stoicism that along with her bubbly demeanour won her several friends. Of course, she was still given to spreading gossip and ingratiating herself with authority – just a bit more discreetly. On at least two occasions she made up a rumour about someone who crossed her that resulted in the woman being expelled from the school. Jennie herself was no angel, and suspicions of petty theft drifted about her during her time in the hospital. No proof ever materialised, though.

Jennie was a favourite among the patients, with her bright and vivacious demeanour. She liked them as well, though in a slightly disturbing way. Later investigations showed that she may have deliberately falsified some records in order to prolong the stay of those she got along particularly well with. She might even have dosed them with the wrong medication in order to make them sicker, though nobody would have suspected “Jolly Jane” of such behaviour. The one sour note in this persona was her attitude towards the elderly patients in her care. She often commented that there was “no use” in keeping them alive, something which people at the time chose to take as a joke. It wasn’t.

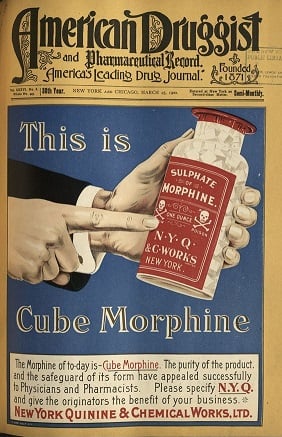

By Jennie’s own count she killed at least a dozen people during her time as a student nurse. She had a passion for pharmacology, and began her career as a poisoner by secretly dosing her patients with opium in order to see for herself the effects that the drug would have on them. Soon she realised that she enjoyed watching them suffer; and the first time one died she was in ecstasy. When the death wasn’t treated as suspicious, she began to escalate her activities. Mixing atropine (a drug derived from belladonna) with morphine ensured the most delightful convulsions and terror in her patients.[1] The fact that morphine contracts th pupils of the eyes while atropine expands them meant that neither symptom would be visible. And the mixture of other symptoms left the doctors who tried to figure out what was wrong with the patients utterly perplexed. The vegetable nature of the poisons also helped to mask them from the analytical techniques of the time. And she even took advantage of her activities to enhance her own reputation; by bringing patients to the brink of death and then nursing them back to health in a “miraculous recovery”.

By the time she finished her training, Jennie had enough of a good reputation to secure a post at the prestigious Massachusetts General Hospital, and she was good enough at her job that initially she was on the fast track to promotion. However this was a tighter ship than Cambridge had been, and she soon got a reputation for taking the credit that others were due. Her tampering with medical records was also detected much more often, though it was put down to incompetence and over-eagerness rather than malice. Nobody suspected that she was still secretly torturing and murdering patients with chemical concoctions. One of those patients, named Amelia Phinney, survived. She later told a story of Jennie getting into bed with her as she was racked with convulsions. Jennie stroked her and kissed her face, telling her that it would all be all right soon. Before Jennie could give her the fatal dose, she was disturbed and had to flee. The next morning Amelia thought that it had all been a fever-dream; and she would not realise differently until years later.

Jennie’s time at Massachusetts General came to an end in 1890. She’d always been a divisive character in the hospital; popular with the doctors for her competence but gradually less and less popular with her fellow nurses. She was a suspect in a number of petty crimes, such as stealing petty cash and the theft of a patient’s diamond ring. (Her more serious crimes were never even suspected.) When she made the mistake of leaving the ward without permission, she was summarily dismissed. Because of this, even though she had passed her final exam and qualified for her diploma she did not receive a license to practice as a nurse.

Jennie worked as a private nurse for a while, before returning to Cambridge Hospital to try to obtain her license there. Her proclivities nearly caught up with her, as an attempt to poison a trainee nurse named Mattie Davis [2] was detected by one of the doctors. Another doctor noticed a tendency for convalescing patients to die in Jennie’s care, though he blamed it on carelessness in administering medication rather than malice. It was enough to make him let the board know, though, and Jennie’s contract was terminated. Once again she failed to receive her license.

With hospital work closed off to her, Jennie decided to go freelance. She even said that she’d do better financially; private nurses did get paid more but she’d lack a steady wage. She’d also lack the oversight which had impeded her activities in the hospital, though she wouldn’t have the steady supply of victims either. But over the next eight years, as Jane Toppan became one of the most successful private nurses in Boston, she still found time to indulge in her appetite for murder.

In 1895 Jennie was boarding in Wendell Street in Cambridge, with an elderly couple called Israel and Lovey Dunham. She decided that Israel was getting too old – in her words, “feeble and fussy”. So she killed him, though it was thought to be a heart attack. Two years later she sent Lovey to join him. It seemed that Jennie still didn’t think there was “much point in keeping old people alive”. She also killed off more than a few of her elderly patients. In one case a family complained to a doctor that they thought Jennie had stolen some clothes from their dead grandmother’s house. The doctor vigorously defended her as “one of the finest women and best nurses he knew”. That she had actually killed the old lady never occurred to any of them.

In August of 1899 Jennie went on holiday in a rented cottage on Cape Cod, something she had been doing for several years. This time she invited her foster sister Elizabeth to join her. Elizabeth was delighted; she was very fond of Jennie and looked forward to spending some time with her. She had no idea that Jennie despised her. Jennie had always despised her. Since they were children and old Ann Toppan had made sure that Jennie knew her place in the household. She was the “Paddy” who was lucky to be there, while Elizabeth was the “real” Toppan. The fact that Elizabeth didn’t believe that in the slightest was irrelevant. She was a symbol of Jennie’s childhood torment, and so she would have to be snuffed out.

Given that, it isn’t surprising that a few days after Elizabeth arrived in Cape Cod her husband Oramel got a telegraph telling him that she was seriously ill. By the time he made it there she was in a coma; the result, he was told by the doctor, of an apoplectic stroke. Elizabeth never regained consciousness before she died the next morning with her husband and her foster-sister at her bedside. If she had she might have been able to tell them of how Jennie had avidly watched as she convulsed in pain before passing out for the final time, with thirty years of spite and hate in her eyes.

Shortly after her sister’s funeral, Jennie decided it was time to make a move on another scheme she had been working on. For several years she had been friendly with Myra Connors, the matron of St John’s Theological School at Cambridge. The friendship had an ulterior motive, of course. The life of a freelance nurse was a difficult one, even though it paid well. On the other hand, Myra’s job came with an apartment, a maidservant and a regular paycheck. So Myra Connors died; of a case of peritonitis that took a decided turn for the worse when her friend Jennie came to nurse her. And at the funeral, Jennie happened to mention to Myra’s boss that it was so sad that Myra died right when she had been planning a sabbatical, and did you know that she had planned to recommend Jennie to fill in for her? When the dean offered her Myra’s job, Jennie played coy but eventually declared that she “owed it to Myra” to take the job. Unfortunately for her though, this time she had severely misjudged her own competence. Her lax attitude to finances combined with her lack of experience in management meant that she was asked to resign after a year. It was a major blow to someone who was utterly convinced of her own superiority.

Jennie consoled herself by returning to the scene of her dearest triumph, the holiday cottage where she had murdered her sister. It belonged to a man named Alden Davis and his wife Mattie, and they had been renting it out to Jennie since 1896. Since they liked Jennie, they’d given her a good rate. And after the events of 1899, they hadn’t felt right asking her for that year’s rent. The next year, in 1900, she’d asked for an extension as she didn’t have enough on hand to pay for the rent. But when she returned to the cottage again and didn’t bother paying then either, Mattie Davis decided to go to Boston and confront her in person.

Having killed her previous landlords, Jennie was now boarding with Melvin and Eliza Beedle who she hadn’t killed – yet. (She had poisoned them at one point though, enough to make them think they had food poisoning.) When Mattie arrive, Jennie gave her a glass of water laced with morphine; and then when Mattie “took over poorly” the Beedles were only too happy to let her rest in an empty room. There Jennie could easily top up the morphine dose with an injection, enough to send Mattie into a coma. Then when the doctor arrived Jennie (who knew that Mattie was a diabetic) told him that she had eaten a piece of cake when she arrived. The doctor had no reason to suspect anything else, and with a nurse already in the house he left Mattie at the Beedles in Jennie’s care. Jennie played with her for a week, varying the dose so that Mattie had moments of lucidity and could speak to her loved ones, before she got bored and ended it all with one last dose.

The Davis family closed ranks after Mattie’s death, and her two daughters Genevieve and Minnie decided to stay with their elderly father for a while. At Mattie’s funeral, they made the fatal mistake of asking Jennie to stay on as their house guest for a while. Jennie amused herself for a while by starting fires around the house (and then inventing a stranger she’d seen “skulking about” to blame for them.) Eventually though her urges returned. Genevieve Gordon, Mattie’s daughter, was clearly suffering in her grief. Jennie decided this was an opportunity, and told Minnie (the other daughter) that she had seen Genevieve inspecting a tin of arsenic in the shed. The two women decided to watch Genevieve carefully in case she did something rash. Then Jennie, of course, murdered Genevieve with arsenic.

Throughout her career Jennie had steered clear of the metallic poisons (too easily detected). This time though, she had plausible deniability to let her experience a new type of death. The stigma around suicide meant that she didn’t have to worry about it being investigated too closely, either. Genevieve’s offical cause of death was recorded as “heart disease”. Two weeks later, Alden passed away from “grief”, given a helping hand by Jennie’s morphia. Then as if driven by a compulsion to “complete the set”, Jennie murdered Minnie only four days later. Grotesquely since the first dose of morphia left Minnie unable to swallow, Jennie administered the fatal dose via an enema. The doctors were baffled, and chalked her death up to “exhaustion”.

The death of an entire family in the space of a month was notable enough that several papers wrote articles about “the unfortunate Davis family”. None of them suspected foul play, though one person did. That was Captain Paul Gibbs, father in law to the unfortunate Minnie. He looked back over the events of the month, and decided that (though he liked Jennie, everybody did) there were some things she’d done that were suspicious. A doctor named Ira Cushing, who was on holiday in the area and who had seen Alden the day before he died, was also sure there was something going on. They got together and decided that something needed to be done. And there was only one man to do it. The governor of Cuba.

Leonard Wood, the US military governor of Cuba at the time, had studied medicine and begun his time in the military as a surgeon but had swiftly moved over into the officer corps. Together with Teddy Roosevelt he had formed the famous “Rough Riders” to fight in the Spanish-American war, and though Teddy got the public glory it was Leonard who was the actual commanding officer. That got him a generalship, and then a post as governor of Cuba. In the summer of 1901 though he was on holiday in his childhood home on Cape Cod when he was visited by an old family friend, Captain Paul Gibbs. Leonard had both the medical connections and the pull to get a full-scale investigation underway.

While the investigation was going on, Jennie paid a visit to her brother-in-law the Reverend Oramel Brigham. In a short space of time she murdered his sister, dosed his food with morphia to make him sick, nursed him back to health in the hope of “winning his affections” and then, when he rejected her advances, took an overdose of morphine herself. Given her experience in medication, it’s likely that she calibrated the dose not to be fatal but it did land her in the hospital. This was a bit awkward for the detective who was following her as part of the investigation, so he faked an illness himself in order to be admitted. After she was discharged Jennie went to New Hampshire to visit an old friend named Sarah Nichols. Luckily for Sarah, an autopsy on the exhumed corpse of Minnie Gibbs found evidence of poison. A few weeks after Jennie arrived, so did the police. Sarah was shocked to see her friend taken away, but the arrival of the police almost certainly saved her life. Because there was nobody Jennie liked to murder quite so much as her friends.

Even though Jennie was only arrested for the murder of Minnie Gibbs, the newspapers soon realised that this was only the tip of the iceberg. There was the rest of the Davis family, of course, but it didn’t take the papers long to find out about the “sudden and suspicious death” of Jennie’s sister Elizabeth Brigham. Serial murder sold papers, female killers sold papers, put the two together and you get the familiar feeding frenzy of the media. There was in-depth analysis of Jennie’s breakfast habits (the fact that she had nothing but coffee for breakfast was clearly a sign of deviance). There was baseless speculation that she was a morphine addict, started by Oramel Brigham himself. Jennie’s only comment was that she wished the papers would not mention her, but of course she was never going to get her wish. And free of all legal shackles, the papers were able to declare her guilt without a shadow of a doubt.

The courts, on the other hand, were not so free. And proving Jennie’s guilt was surprisingly problematic – given that she was guilty. Her defence had two big boons at the start. The first was the recent eath (of natural causes) of the Davis family doctor, Leonard Latter. This meant that Jennie could claim that his evidence would obviously have cleared her. The other was down to a faulty assumption by the prosecutors. They had initially arrested Jennie because they found arsenic in the corpse of Minnie Gibbs and of Georgina Gordon. But though Jennie may have poisoned Georgina with arsenic, she hadn’t used it on Minnie. In fact, the arsenic came from the embalming fluid used by the local undertaker. Despite this the prosecution continued to fixate on the idea that both women had been poisoned with arsenic, inadvertently undermining their own case.

It was a newspaper interview with Captain Paul Gibbs that broke the case open and doomed Jennie. When a reporter from the Boston Journal asked him for his opinion about the arsenic found in the corpses, Captain Gibbs was surprised. He said “I didn’t think Jennie Toppan would use anything as easily detected as arsenic”. The captain, of course, knew that Jennie was far smarter and a more capable pharmacologist than the prosecutors were willing to admit. When he was asked what he thought she might have used, he suggested a mixture of morphine and atropine; like Jennie he knew that this would make the most common symptoms of the two poisons (contracting and expanding the pupil) cancel each other out. He also pointed out that Jennie had owed the Davis family money, and that $500 which Alden had in his pocket when he died had gone missing. In short, Captain Gibbs did more to build the prosecution case in one interview than the prosecutors had managed so far.

With this motive set out, the papers soon found more and more evidence of Jennie’s sticky fingers down through the years as well as the mysterious deaths that benefited her financially. Myra Connors, for example, was soon being laid at her feet. It was the Boston Herald that got the next big scoop though, when it got hold of a woman named Jeannette Snow. Jeannette was Jennie’s cousin…or rather, Jeannette was Nora Kelley’s cousin. Through her the history of “Kelley the Crack” and her childhood mistreatment, along with Jennie’s birth sister Nellie having ended up in an asylum, seemed to confirm what many newspapers had already suggested. That Jennie Toppan was not just an opportunistic poisoner after material gain, but that she was in fact dangerously insane.

The idea of examining Jennie’s sanity rather than prosecuting her became more palatable to the state day by day. Her wealthy Boston clientele (those she hadn’t murdered, anyway) were writing letters and using their influence to support her; as none of them could believe her guilty. In addition, the case she was being charged with (the death of Minnie Gibbs) was a lot more difficult to prove than they’d thought. And then there was a breakthrough. The inquest on Georgina and Minnie proved what Captain Gibbs had suspected: that Minnie had been murdered with a mixture of atropine and morphine. The method pointed to a trained medical professional, putting Jennie right in the frame. And though they hadn’t been able to show any evidence of Jennie buying arsenic, as soon as they started looking into her purchases of morphine they hit the jackpot. In fact, they had more than enough evidence to go to trial.

The original date for Jennie’s trial was April of 1902, but with this evidence in hand the prosecutors decided to ask for a special Grand Jury session to be convened in December of 1901. This was done, and before the prosecution had finished presenting their case the jury indicted her for trial. But the trial never took place. Jennie’s court appointed attorney, Fred Bixby, and the District Attorney agreed that neither wanted to deal with the insanity defense in court, with a parade of expert witnesses for each side. Instead they agreed to appoint a panel of eminent psychiatrists to examine Jennie and to reach a conclusion that would stand up on its own in court. In March of 1902 the three men (Dr Henry Stedman, Dr George Jelly and Dr Hosea Quinby) began their exploration of Jennie’s psyche.

At first Jennie was suspicious of the doctors, but soon her natural chatty nature reasserted itself and she opened up to them. They quickly picked up on her pathological addiction to lying, but the doctors were experienced enough to push past that. Eventually, despite her “Not Guilty” plea at the arraignment, Jennie confessed to the murders. And to other murders. With a degree of calmness and an utter lack of remorse that chilled these men, experienced “insanity experts”, to the bone. When she revealed her habit of getting into bed with her victims, and the sexual thrill she got from watching them die, it was unlike anything they had ever encountered in their previous experience. Under the old M’Naghten rules, Jennie would not have been entitled to an insanity defense. She knew what she was doing was wrong (even though she seemed incapable of internalizing why). Nonetheless the three doctors unanimously declared her “morally insane” (the term used for psychopathy at the time) and that she was unfit to stand trial, but would never recover from her illness.

Though there was technically no need for a trial following this, the State Attorney General decided to hold one anyway in order to avoid establishing the precedent that a medical decision like this did not require jury approval. By the time the trial took place, enough of the report on Jennie’s sanity had leaked out that she was regarded as the greatest monster in American history. A serial killer had never been prosecuted in America before, at least not one recognised as such. Almost everyone recognised the trial as a formality, including Jennie herself. She was smiling and chatting with her lawyer during the single day that it took the jury to agree that she should be sent to a mental institution for the rest of her life. Perhaps the most decisive piece of evidence was when Dr Stedman was asked what reason Jennie had given for poisoning Minnie Gibbs, and he replied:

To cause death.

It was only after the trial that Jennie’s attorney revealed the shocking truth that Jennie had confessed to him when he became her attorney six months earlier. The eleven deaths that the police were investigating were only the tip of the iceberg. She told him how she had begun her career in murder fourteen years earlier at nursing college, and in that time she estimated that she had killed thirty-one people. Only the Attorney General knew of Jennie’s confession before the trial, which was why he had agreed to appoint the panel of experts. Those experts were themselves utterly shocked by this revelation. And the press, predictably, went wild.

The Boston Globe said that she was “the greatest criminal in the country”. The Boston Post had a page one story comparing Jennie to the greatest poisoners in history. They confidently asserted (incorrectly, as it turned out) that she would be “one of the most noted poisoners the world has ever known”. A few days after the trial, the New York Journal published her “terrible confession”. [3] In giving evidence at the trial, the psychiatrists had glossed over the more lurid details. The Journal went into them in graphic detail. Though the confession was almost certainly written by one of Hearst’s staff writers, it still stuck mostly to the facts. And those facts painted Jennie as an even greater monster than anyone had suspected.

At Taunton State Hospital, Jennie was to all appearances an exemplary patient. Given the state of psychiatry at the turn of the century, a “lunatic asylum” was a deeply unpleasant place, but a patient apparently in full possession of their faculties (like Jennie) was enough of a rarity that she was almost a favourite of the staff by default. In fact, during her initial few years at the asylum, Jennie quite enjoyed it. However after a while the old adage that “nothing would send someone crazier than being in an asylum” seemed to take effect. (In fact, Jennie may have been on a downward slope for some time. But the asylum certainly didn’t help.) She developed manic depression, which led to her taking increasingly bizarre notions such as the idea of resuming her birth name and becoming a nun. By 1904 she became so paranoid that she refused to eat anything for fear it would be poisoned, an ironic symptom that led to a new rash of press coverage of her case. The articles were predictably gloating in nature, with the usual journalistic glee in the suffering of those they considered deserving of it. They happily contemplated her death, and the end of their twisted morality play. But she didn’t die.

Jane Toppan finally passed away in 1938, eighty-one years old and still imprisoned in Taunton. By the end she was just another inmate. And though her death did prompt a new wave of interest, with front page stories in the Boston neswpapers and an obituary in the New York Times, nowadays she doesn’t have anywhere near the notoriety you might expect. A few biographies, [4] and a role as one of the killers delivering monologues in Anne Bertram’s play Murderess – that’s about it. Perhaps it’s a subconscious act of repression that keeps her obscure. Perhaps we just don’t want to think that when we place our lives in other people’s hands, we don’t really know who that person really is. If we spent too long thinking that the friendly nurse on our ward might be a “Jolly Jane”, then nobody in a hospital would ever dare sleep again.

Pictures via wikimedia and Criminalia except where stated.

[1] Her preferred delivery method was in a glass of fizzy mineral water, which perfectly disguised the concoction. Interestingly she was extremely brand-loyal to Hunyadi mineral water, though they probably didn’t appreciate the endorsement.

[2] No relation to the Mattie Davis who Jane would later murder.

[3] The Journal, a Hearst paper, had also published the confession of HH Holmes

[4] We recommend Fatal: The Poisonous Life of a Female Serial Killer by Harold Schechter