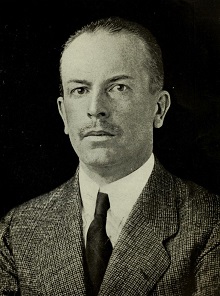

Count Johann von Bernstorff, Ambassador and Spymaster

Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff was born in London in 1862. His father Albrecht was a Prussian Count and experienced diplomat who had just spent seven years as the Prussian ambassador to Great Britain. Shortly before Johann’s birth he had been recalled to Berlin where he had been promoted to Prussian Foreign Minister This was the third time he’d been offered the position, but this time he clearly felt he could do something with the job. He did firmly set a direction for a German union that would exclude Austria, but that was about the only major achievement of his ministry. In a constitutional crisis triggered by the Landtag’s refusal to pass the King’s budget, Albrecht and several other ministers offered their resignations in an attempted power play. As so often happens, the King chose to accept their resignation leading to Albrecht being replaced by the legendary German statesman, Otto von Bismarck. Albrecht’s bitter comments about the man who replaced him would blight his son’s early career.

Forced out of the ministry, Albrecht was re-appointed as Prussian ambassador to Great Britain, becoming German ambassador after the new nation was officially established in 1871. He died in 1873 when Johann was only 11 years old. Young Johann moved back to Germany after his father’s death, and attended school in Dresden. His childhood ambition was to be a diplomat like his father, but Otto von Bismarck’s enmity for the family meant that he couldn’t get a job in the government. The old man would remain both Chancellor and Foreign Minister until 1890. With no chance of a diplomatic career for the moment, Johann joined the army instead. He was commissioned as a lieutenant and in 1887, at the age of 25, he got married.

His new wife was Jeanne Luckemeyer, the daughter of a German named Edward who had emigrated to New York and become a successful textile importer. Edward was best known for the “Luckemeyer Dinner” that took place at Delmonico’s Restaurant in 1873. He had unexpectedly received a $10,000 rebate on his import duties, and since he was already a millionaire several times over he decided to spend it all on one glorious night at the greatest restaurant in New York, giving the proprieter a free hand to put on the best show he could conceive. Edward and 71 guests were seated at a gigantic ring-shaped table. In the center was a thirty foot long country diorama centred around a lake, complete with four swans and a waterfall. [1] It was the talk of the town, deeply annoying all the members of New York’s insular upper classes. Little irked them more than being upstaged by an immigrant who had the effrontery to work for a living.

Jeanne’s mother Helen died when she was quite young (leading to a later scandal when her father remarried to Jeanne’s governess). When and how she met Johann is not recorded, though it was likely in one of the salons or court functions that the dashing young lieutenant caught her eye. The pair were married on his twenty-fifth birthday. Jeanne reputedly had connections in the Imperial German court through her mother’s family, and this might be what finally led von Bismarck to relent in his attitude towards the von Bernstorff family. In 1888 Johann was stationed with the embassy in Constantinople, a symbol that von Bismarck no longer considered him persona non grata. In 1889 Johann retired after eight years in the army, and in 1890 he went to Berlin to take the two-year course followed by the exam for entry into the diplomatic service. It was around this time that he and Jeanne had two children – a girl named Luise who was born in 1888 and a boy named Christian-Gunther who was born in 1891. Finally in 1892 he received his first diplomatic posting.

Johann spent the next ten years effectively serving his apprenticeship in the diplomatic trade by acting as a legation secretary for various embassies around Europe. During this time he gained a reputation as one of those who advocated for Germany to maintain peaceful relationships with the rest of Europe, in contrast with the increasingly hawkish mood that had come to dominate national politics since von Bismarck’s retirement. In 1902 he was appointed as a counsellor to the embassy in London, returning to his old childhood home. In 1906 he had his first major post when he was appointed as a consul general in Cairo. This was soon followed by a career-defining posting. Count Johann von Bernstorff was officially appointed in 1908 as the German Ambassador to the United States of America.

The dapper and charming German ambassador, with his perfect English (he had been raised bilingually in London) and his beautiful American wife on his arm were an instant hit in Washington society. In this pre-World War era German-Americans formed a distinct cultural group and Johann was easily able to forge links with politicians seeking their votes. That’s not to say that there weren’t points of contention to negotiate, though. Prior to his arrival, for example, America and Germany had been involved in a proxy war that had nearly turned into a direct war over control of the Samoan Islands, which had eventually been resolved when they divided them up and each took half as colonies. (The natives were, of course, not consulted.) Several years into Johann’s embassy tensions once again grew between the two countries, this time over Mexico. The US supported President Francisco Madero when he took power in 1911. When he was assassinated in 1913 and Victoriano Huerta took power, the US opposed him but he was supported by German financial interests (and the German government, who hoped to get a Caribbean naval base out of him). This escalated to US military action when they shelled and occupied the Mexican port of Veracruz in order to prevent a German ship from delivering weapons to the regime in early 1914. [2] Tensions between Germany and America over this had just been smoothed over by June of 1914. Then an obscure Serbian terrorist group assassinated the heir to the throne of Austria and his wife, lighting the fuse that would ignite a tinderbox of hellish proportions.

It’s been argued that World War I was a direct consequence of the elaborate scheme of alliances built up by von Bismarck and the European diplomatic class in the late 19th and early 20th century. Whether that’s true, or whether the war was an inevitable consequence of a fragmented and highly militarised Europe, the end result was the same. Between the assassination in June and the official outbreak of war in August, Johann was recalled to Berlin in early July of 1914. There he was officially inducted into the German intelligence service, and given his brief for how he could serve Germany in the coming conflict. Officially his main job was to sway America to support Germany directly or indirectly, or at worst to keep them officially neutral. Unofficially his job was to do whatever could be done to hinder support to the Allies from America. In August of 1914 he returned to Washington and began his mission. At first this consisted of helping German-Americans (through means both legal and illegal) to return to Germany to fight for their fatherland, but soon it took a more explosive turn.

World War I was a huge economic boost to the USA. In fact, it could be argued that World War I was what transformed it into a superpower, through the enormous amount of capital that was transferred from Europe to America in order to pay for the armaments that fed the great war machine. Initially those armaments were intended for both sides, but by November of 1914 the great British Navy had blockaded Germany and its allies. As a result the arms manufacturers followed their greatest loyalty – money – and made their sales to the Allies. So Johann decided that the friend of his enemy was his enemy, and began an infamous campaign of direct sabotage against the US arms industry.

The earliest of these was what was known as the Great Phenol Plot. Phenol is an organic compound that has a tremendous number of industrial uses. Nowadays it’s mostly used in the production of plastics, but in 1914 it was mainly used to create aspirin and high explosives. Naturally the latter increased dramatically during the war, which was a blow to pharmaceutical companies. One such was the German company Bayer, whose US-based aspirin factories took a major hit just as the patent for aspirin was expiring. At the time Thomas Edison was setting up a phenol factory in America to supply his own businesses. (Phenol was also used to produce records.) Normally his excess production would probably have gone into arms production, but with funds supplied by Johann von Bernstorff a shell corporation was set up to buy it all and funnel it into Bayer. Though this wasn’t actually illegal (and the operation did actually turn a profit after the initial investment), when it was exposed in the American press the negative publicity forced them to wind the scheme up. Still, it raised about two million dollars, prevented the production of over two thousand tons of high explosive and helped to keep Bayer’s American enterprises solvent through the war – a notable success for Johann’s operations.

One of Johann’s most active agents in the early part of the war was Franz von Papen, a junior diplomat who had served in the German embassy in Mexico during the revolution and who was appointed Military Attache when war broke out. Von Papen was originally responsible for the New York operation that produced forged documents to allow Germans living in America to get through the blockade and to Germany. He was also a liason with Indian activists acquiring American weapons for a possible revolution. However he’s most infamous for his operation to blow up the Vanceboro Railway Bridge, a key link between the US and Canada. Franz recruited a German army reservist (who had been travelling in Texas when war was declared) named Werner Horn to carry out the actual bombing. Werner was given a suitcase full of dynamite which he placed at the base of the bridge. The damage was minor and Werner was soon caught and arrested. He gave up von Papen under interrogation, and though von Papen could not be arrested due to diplomatic immunity he was declared “persona non grata” and deported to Germany. [3]

One of the biggest problems Johann von Bernstorff faced was his subordinates, who were simultaneously consumed by rivalries and utterly terrible at keeping secrets. Nowhere was this clearer than in their dealings with the former Mexican leader Victoriano Huerta when he fled to New York in 1915. Three of Johann’s lieutenants all tried to negotiate an agreement with him. In addition to von Papen (as this took place before his deportation), there was Karl Boy-Ed (the Naval Attache) and Franz von Rintelen (a Naval Intelligence officer). All three did their best to undermine each other and convince Huerta that they were the only one he could negotiate with, and all of this infighting prevented them from realising that US intelligence had thoroughly compromised their meetings. Though they did make a deal to supply Huerta with weaponry, he was arrested in Texas as he made his way to cross the border. He died in a US military prison the following year.

Like von Papen, Karl Boy-Ed was deported in 1915. This left Franz von Rintelen as Johann’s most visible field agent. Despite him having been “marked” by US intelligence, he still managed some notable successes. As well as organising strikes by munitions workers and attempting to buy out any companies he could, von Rintelen recruited Irish dock workers with Republican sympathies to hide “pencil bombs” on ships transporting weapons to Europe. These were incendiary devices about the size of a cigar; lead tubes that contained a mixture of acids separated by a copper disc that they would eat through. When the acids mixed they would produce an intense flame that would set fire to almost anything, and also melt the lead of the tube (helping to conceal the source of the fire). They were very successful, though it’s reported that von Rintelen had to stop supplying them to the Irish workers after they started putting them on every British ship and not just those transporting weapons.

Von Rintelen was probably involved in the most infamous action by German saboteurs in America – the “Black Tom” explosion. Black Tom was an island in New York harbour, off the coast of Jersey City, that was used as a marshalling yard by all the munitions companies selling to the Allies. Exactly how the German operation is not known, but they may have infiltrated the guards on the depot. Two German spies later identified that were probably part of the operation were Kurt Jahnke and Lothar Witzke, but the only person ever definitively identified as part of the plot was a Slovak immigrant named Michael Kristoff. However it was accomplished, on the night of July 30th several small fires (probably started by pencil bombs) broke out in the depot. The first explosion went off at 2:08am, and was so massive that it was felt in Philadelphia. Fragments from the explosion caused damage to the Statue of Liberty, and thousands of windows were blown out throughout Manhattan by the blast. The second major explosion took place half an hour later, and more came as the fire raged through the yard. In all the explosions caused twenty million dollars of damage (around half a billion in today’s money) and killed between five and seven people. Perhaps the most extraordinary thing is that it wasn’t until twenty years later that it was determined that this was the result of German sabotage. [4]

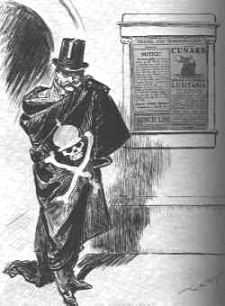

Johann was involved in many other activities during the war (including acting as a contact point for Germany to the American representatives of both Indian and Irish rebels), [5] but his overt role of keeping America out of the war was always a difficult one. The German policy of “unrestricted submarine warfare” in the Atlantic (ie sinking any ship they found) was always going to turn the American public against them. The Lusitania is the most famous example of this, but it was just one of many ships which would be considered illegitimate targets today that fell victim to the practice. As a result the Germans were forced to temporarily call a halt to it. The final straw however was a telegram from Arthur Zimmerman, the German Foreign Secretary, to the German ambassador in Mexico. The Germans planned to resume their submarine attacks and had no doubt that this would lead to America entering the war. The telegram contained instructions to try to persuade the Mexican government to invade the southern US in order to open up another front in the war. Though the Mexican government would never actually have gone along with this, it didn’t actually matter in the end. The British had tapped the cables, and the British had broken the German codes. On the 3rd of February Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare and the US severed diplomatic ties, leading to Johann being sent back to Berlin. On the 19th the British handed the Zimmerman Telegram over to the Americans. [6] As a result public opinion was shifted enough to overcome the anti-British prejudices in much of the country and America was able to enter the war in April of 1917.

Johann von Bernstorff returned to Berlin to a mixed reception. Though he had probably done far better than anyone could have reasonably expected in America, the Imperial German command were well known for their unreasonable expectations. He hadn’t played any part in getting America into the war, but to the average German he was still a failed ambassador. He spent six months officially “retired” from diplomacy, but in August of 1917 he was sent out as ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Germany’s allies in the war. He had a hard time with the Ottomans, who by this stage in the war had lost all respect for the Germans and were mostly occupied in try to secure their own future. One of the most significant parts of this embassy came when Johann was (in line with German policy) issuing protests against the genocide of the Armenian people being conducted by the Turkish army. Johann’s memoirs record a chilling conversation he had with Mehmed Talaat, one of the three Pashas who ruled Turkey at the time:

When I kept on pestering him about the Armenian question, he once said with a smile: ‘What on earth do you want? The question is settled, there are no more Armenians.’

When the war ended, Johann was part of the German diplomatic team who negotiated the terms of Germany’s surrender and the post-war treaties. He was the head of the preparatory committee, due to his experience with the Americans who were seen as the arbitrators of the treaty. While the treaty was under debate he was offered the position of Foreign Minister, but he was well aware that this was effectively being asked to be the scapegoat for the terms of whatever treaty came out, especially since Germany was not being permitted a place in the negotiations. When the Treaty of Versailles was published, Johann was one of the few pragmatists who dared to go against German public opinion and say that they should accept it as the best deal they were going to get, something that would later cause him serious trouble.

In the wake of the war a bloodless revolution saw the Kaiser ousted from power and replaced with the Weimar republic. Johann helped found a new party called the German Democratic Party, which his nephew Albrecht (a junior diplomat, as was the family trade) also joined. [7] He served as a member of the Reichstag from 1921, and was also a strong advocate for German involvement in the newly formed League of Nations, founding a society dedicated to promoting that aim. Another cause he was involved in was Zionism, supporting the re-establishment of a Jewish homeland in the Middle East. He also published his memoirs, where he argued that America’s involvement in the war was not inevitable and could have been avoided by a more measure approach to warfare in the Atlantic. He also denied any involvement in German sabotage activities in America and laid the blame for them on Franz von Papen, though in the end this probably harmed Johann’s political career and aided von Papen’s.

Throughout all of this, Johann became more and more a target of right wing extremists. The face-saving myth of the “stab in the back” (an erroneous belief that Germany could have won the war but was betrayed, used for propoganda purposes by the Nazi party) that was so popular among German military veterans had Johann as one of its key villains. Ironically it was often claimed as part of this that he had been an American agent during the war. As with much Nazi rhetoric, these violent words led to violent actions and several of Johann’s friends were murdered during Hitler’s rise.

After he had left the Reichstag Johann had become leader of the German delegation to the World Disarmament Conference, a League of Nations attempt to de-escalate military buildup around the world. Though the effort was doomed to failure, it did give Johann a good opportunity to leave Germany and simply seek asylum in Geneva. In 1933 he and Jeanne just didn’t return to Berlin. Geneva wasn’t just a refuge for Johann and Jeanne – their daughter Luise had married a Swiss nobleman and lived there with her children. Johann died in Geneva in October of 1939, a month after the outbreak of World War 2 in Europe. His wife Jeanne returned to America, where she died four years later. Both deaths went largely unreported. In the tumult of a new world war, people had little time for those who had been so central to the one before.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] The swans were kept from flying off by a golden cage reaching to the ceiling that enclosed the entire centerpiece.

[2] An event memorialized in a great Warren Zevon song.

[3] Fritz von Papen later became a politician and was responsible for negotiating the coalition that resulted in Hitler becoming German Chancellor.

[4] A judgement for damages was issued against Germany at that point under the post-war treaties, but the Nazi government (who were in power at the time) refused to pay. It was eventually paid by the West German government in the 1950s.

[5] Whether Johann had any connection to the mysterious “Madame H” who Jack Garland was mistaken for later in 1917 is impossible to tell.

[6] They had to use a great deal of subterfuge to prevent the Americans realising that they had obtained it by tapping the same cables that transmitted American diplomatic messages.

[7] Albrecht would go on to be a voice against the Nazis before World War 2 and a leading figure in the internal German resistance after war broke out. He was briefly imprisoned in Dachau in 1940, and was re-arrested in 1943. He was held prisoner for over two years before being executed without trial by the SS in 1945 when the prison which held him was about to be taken by the advancing Russians.