John Tawell, Forger and Murderer

We live in an increasingly interconnected world. A friend may live on the other side of the planet, and yet their words appear on your computer screen to tell you how their day is going. You can pick up your phone and chat to people on other continents. Information flashes from one place to another in an instant. In times gone by it was easier to get ahead of the information, to outrun your deeds and leave them behind. But those times are gone. And the first person to find out this aspect of the new world we live in was John Tawell.

John was born in Norfolk in 1784. His father Thomas was a shopkeeper, but far from a rich one. Once John finished his schooling he was expected to find his own means of support. In 1798 he went to work in a general store in Pakefield in Suffolk. It was owned by a widow who was a member of the Society of Friends, better known as the Quakers. She encouraged her employees to attend Quaker meetings, and young John was one of those who went along to them and became a member of the Society. It may have been business sense rather than religious conviction which sent him to these meetings, as there were many successful Quakers in business at the time (and others who would find their success at this time). Reputedly one of the connections he made was to a young businessman named Joseph Hunton, who was living in Suffolk at the time.

In 1804 John moved to London, where he found work at a drapers owned by a Quaker named Jansen. He did well in the job and gained a good reputation with the local society. His reputation took a bit of a hit though when Mr Jansen found that John had been having an affair with his housemaid Mary, who was now pregnant. Mr Jansen fired the pair of them, though when John married Mary he was allowed to rejoin the Quaker community. The pair had two sons, and John found new work at a chemist’s store in Cheapside. Outwardly he was a pillar of the community.

Of course, the nature of Victorian London was that many “pillars of the community” were also enthusiastic supporters of the city’s grimy underbelly. The refusal of the “respectable” community to acknowledge the basic humanity of those caught up in the city’s flourishing sex trade, for example, allowed them to be exploited, chewed up and eventually destroyed in order to sate the lusts and empty the pockets of “respectable” men like John Tawell. Those empty pockets needed filling, though. And in order to finance this part of his life, John risked his neck by passing forged banknotes.

John was caught in 1814 trying to pass a £10 banknote drawn on Smith’s Bank. Forgery was a capital offense, as was the case for a vast number of offences at the time. John was lucky in his choice of victims, though. Smith’s Bank was run by Quakers, and Quakers were firmly and vocally opposed to the death sentence on religious grounds. It’s not unlikely that others in the church put pressure on the bank’s owners. Quakers sending a Quaker to the gallows would not have been a good look. With their testimony and his “good character”, John’s sentence was commuted to transportation. He was deported to Australia as a convict.

John had a sentence of 14 years and he spent the first few of those working on coal ships before his pharmaceutical experience got him a transfer to work in a hospital. It was a “convict hospital”, which mostly treated convicts as the name suggests. Since convicts were effectively indentured servants hired from the government, it was up to their masters to pay for their treatment. The hospitals also provided free health care to the poor, but those with funds were expected to pay their way. It was a fairly cushy post, and it also provided John with a chance to increase his skill in the pharmacy. At some point he moved from the hospital to working as a clerk. In 1819 he received his “ticket of leave”, a document entitling him to relative freedom on parole. With that he was able to apply for a conditional pardon in light of good behaviour. This would make him effectively a free man, except that he could not return to England before his sentence elapsed. This was granted in 1820.

Now that John was free, he was able to make a shot at respectability. He had seen an opportunity in Sydney, which lacked much in the way of an apothecary at that time, and so he had sent off to England for a load of medicine that he could package and sell in the colony. In the advertisement he stressed that “his qualifications are neither unprofessional or irregular” – somewhat of a stretch of the truth. In a later advert he listed the medicines he had on offer as:

Fine Sago, Arrow Root, Castor Oil, Cheltenham, Epsom, and Glauber’s Salts, Senna, Paregoric Elixir, Dalby’s Carminative, Godfrey’s Cordial, Turlington’s Balsam, Opodeldoc, Extract of Lead, Sulphur, Ointments, Cerates and Plasters, &c. &c.

His reputation received a boost when a board investigating the qualifications of medical men in Sydney certified that he did actually know his trade, and by 1823 he was able to send for Mary and his two sons to come and join him in the colony. By 1824 his sons John and William were attending Sydney Grammar School and in 1825 John became a governor of the school. He also became a partner in the Bank of New South Wales, a sign of both his prosperity and his respectability. In 1826 he put his business up for sale as he was suffering ill health, but he seems to have found no buyers as in 1827 he was still advertising from the same address. In 1827 he put it back up for sale, advertising it as “the first establishment of its kind in this colony”. This time he included in his reasons for selling it his “intention of returning to England”, which he would legally be able to do the following year. However his initial sale, to one of the other partners in the bank, fell through and he was not able to leave Sydney in 1828 as he had hoped.

By 1829 John’s patience had run out, and rather than wait for his business to be sold he appointed an agent to act on his behalf and set out for England. He had a grand time lording his success over his old compatriots, though one was notable by his absence. His old friend Joseph Hunton had been arrested and executed the previous year. His crime had been the same one John was arrested for many years earlier. Forgery. Joseph’s crime was an order of magnitude greater than John’s, though. Joseph had been passing noted worth hundreds of pounds, and his were drawn on the much less forgiving Bank of England. His association with John had led to John’s old crimes being talked about in the press, which might be why John changed his mind about returning to England. Or it may have been the stink of London in the Industrial Age, a far cry from the clean air of Sydney. So John returned to Australia and to his relative respectability.

Eventually John gave up on selling his business, and instead simply installed his eldest son John as the proprietor. John the younger had trained as both a surgeon and a pharmacist, so unlike his father his qualifications actually were “professional and regular”. John senior now settled in to life as a philanthropist and man of finance. He gifted a hall to the local Quaker society, and sponsored the founding of a school for girls. (Though what John was most remembered for in Sydney was when he decided suddenly in 1836 that dealing in rum and spirits was immoral, and dumped his entire stock – some 600 gallons – into Sydney harbor.) Life was good. At least for a while. Sadly the family’s ideal life was soon subjected to multiple tragedies. In 1833 young William (who would have been around twenty years old or so) died, and five years later John junior (by now in his mid-thirties) also passed away. These tragedies took their toll on Mary Tawell, and she fell ill. She and John returned to England, possibly in order to be closer to their remaining family (such as John’s brother William). They bought a house in Southwark, but it soon became clear that Mary was not going to get better. To look after her in her final days, John hired a young woman named Sarah to take care of her. That was where the real trouble started.

Sarah’s surname is a matter of some confusion. Some sources give it as “Lawrence”, others as “Hadler”. The historian Carol Baxter wrote in The Peculiar Case of the Electric Constable that Sarah was born Sarah Lawrence as the illegitimate child of Grace Lawrence, and then took her stepfather’s surname of Hadler after he remarried. (Confusing matters is that Sarah would later give herself a third fictitious surname.) Sarah had been in service since her teens, mostly to Quaker families though she was not one herself. She had always left her employers on good terms, and they had recommended her to others in their community. Sarah was in her early thirties in 1838 when she came to take care of Mary, and despite (or perhaps because of) the extreme situation sparks flew between her and the fifty-four year old John Tawell. Whether they began having an affair before or after Mary’s death is unknown, but at some point they began a physical relationship that ended with John making Sarah his mistress.

John installed Sarah in a house in Salt Hill in Slough, where she told the neighbours that her name was Sarah Hart and that her husband Alfred was working overseas. She explained John’s visits as him being her husband’s employer, and that he was delivering her allowance from her husband’s salary. She had two of John’s children while she was living in Slough – Alfred, named for his fictitious father, around 1840 and Sarah in 1843. How she explained their arrival to the neighbors is unknown, but she kept on good terms with them. Perhaps she might have hoped that John would make her his wife, but more realistically she probably knew exactly the position she was in and she made her peace with it. She was far from the only mistress installed in London’s satellite towns in this way. Whether she knew that John had actually remarried in 1841 to another young woman is entirely another matter.

John’s second wife was named Sarah, just like his mistress. Her surname was Cutforth, and she was a young Quaker widow who ran a school at Croydon in London. She had a daughter named Eliza from her first marriage, who reportedly was less than pleased that her mother was remarrying. She was not the only one who was displeased, as John was considered “lapsed” by many in the Quaker community. Though he still wore their dress and followed many of their customs, they still thought that Sarah was marrying “an unbeliever”. Still she seems to have found John attractive enough that she decided to risk their displeasure and marry him. John’s motive for marriage seems to have been more pecuniary, as his Australian businesses were in a sorry state without him there to keep his schemes going. Sarah Cutforth came with a sizable fortune, and so after they were married John was once again able to live in the manner he had grown accustomed to.

John and his wife Sarah had a son in 1843, who must have arrived sometime around the same time as his half-sister Sarah. He was named Henry. Unlike the children who were hidden away in Slough, his birth was celebrated. In fact by now John had almost cut off all contact with Sarah Hart, and only visited her each quarter to pay her allowance. His “real” family lived in a big house in Berkhamsted, which outwardly John could easily afford. However the financial strain of maintaining two separate families was very real, and by 1844 it was clear to John that something was going to have to be done. For a man of few scruples, the solution to his problem was as obvious as it was horrific.

It was around six or seven o’clock on the night of the 1st January 1845 that Mary Ann Ashlee began hearing noises of distress from the house next door through the adjoining wall. She knew that Sarah Hart had a visitor, and she’d heard raised voices earlier. The visitor was old Mr Talbot, the Quaker who paid Sarah her husband’s salary. Mary had passed him in the road earlier. But this sound was different, and Mary decided to investigate. As she came out of her house, she saw Mr Talbot leaving Sarah’s house. He was having some difficulty opening Sarah’s front gate, and as Mary helped him with it she noticed how agitated he seemed. It wasn’t until after he had left and she went into Sarah’s house that she understood why that was.

Mary found Sarah lying on her kitchen floor, frothing at the mouth and almost unconscious. Her clothes were torn from writhing around, but she was almost unconscious by this point. Mary ran to get another neighbour and sent them for a doctor, then returned to Sarah and tried to rouse her. But both she and the doctor (when he arrived) were unsuccessful. Sarah Hart had been poisoned with prussic acid, otherwise known as potassium cyanide. It would have reacted with her stomach acid to produce hydrogen cyanide, which caused her body to become unable to use the oxygen in her blood. By the time Mary had found her, her brain would have been shutting down from hypoxia and she was effectively already dead. She was the first recorded person in history to be murdered with cyanide, [1] but she would be far from the last.

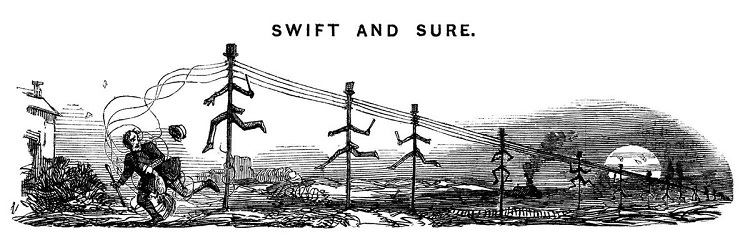

One of the first people to arrive at the scene was the local vicar, the Reverend E. T. Champnes. He realised that Sarah had been murdered and immediately raced off to try and catch “Mr Talbot”. He wasn’t fast enough to get to the station before John boarded the train to London, but luckily Slough was one of the stations that had been equipped with a telegraph to send messages up and down the line. The telegraph had only been installed a few years ago, and was still a relatively new invention. The station master, a Mr Howell, sent a message to Paddington that would prove to be Nemesis for John Tawell:

A MURDER HAS GUST BEEN COMMITTED AT SALT HILL AND THE SUSPECTED MURDERER WAS SEEN TO TAKE A FIRST CLASS TICKET TO LONDON BY THE TRAIN WHICH LEFT SLOUGH AT 742 PM HE IS IN THE GARB OF A KWAKER WITH A GREAT COAT ON WHICH REACHES NEARLY DOWN TO HIS FEET HE IS IN THE LAST COMPARTMENT OF THE SECOND CLASS COMPARTMENT

The spellings “gust” and “Kwaker” was needed as the two-wire telegraph system had no codes for J, Q or Z. This almost led to disaster as the operator at Paddington initially thought that “KWA” was a sign of a bad line and asked for the message to be repeated. However they made sense of it in time, and when the train arrived in Paddington it was being watched by Sergeant William Williams of the British Transport Police. As a member of the BTP he had no authority to arrest John, so instead he put on a coat over his uniform to disguise that he was a policeman. Thus hidden, the sergeant followed him onto the omnibus that he boarded. He tailed John to the Jerusalem Coffee House, and from there to the house in Berkhamsted. After he was sure that John was not coming out, he went to the local Metropolitan Police station where he met up with an Inspector Wiggins. The next morning the two men went to the house, and John Tawell was arrested for the murder of Sarah Hart.

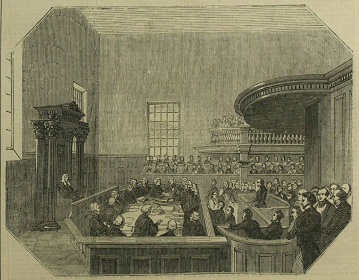

The murder of Sarah Hart was a sensation, of course. Murder trials were the fodder of the new mass media at the time. The use of the telegraph to apprehend John loaned the whole thing an exciting scientific air, and was largely responsible for bringing its ability to transmit information at speed to public attention. The trial itself was pretty much a foregone conclusion from the start. John’s initial defence was to deny that he had been in Slough, which was of course easily disproven. The evidence that Sarah had fallen ill suddenly after his previous visit was also pretty damning. The biggest piece of prosecution evidence, though, was that John had bought “two drams of prussic acid” that very morning. It was an open and shut case.

His lawyer, Sir Fitzroy Kelly, nevertheless did his best to save John from the noose by attacking the idea that Sarah had been murdered at all. Since this was the first ever case of cyanide poisoning being used to kill somebody, he was able to argue that the doctors had no experience in it and that there was no evidence that the quantity of cyanide found in the stomach was a fatal dose. It could have come from the pips of an apple she had eaten, since they were known to contain a small amount in traces, and built up in her stomach. However in his summing up the judge gave guidance to the jury that if the circumstantial evidence (John’s presence in the house, his having bought the poison and so on) pointed to poisoning by an individual sufficient to convince them of his guilt, then scientific certainty was not required. It was an important legal precedent without which it would have been impossible to convict poisoners, and it was enough to send John Tawell to the gallows. [2]

John was executed on the 28th March 1845, two weeks after his conviction. His family were left to pick up the pieces. The two “Hart” children went to live with their grandmother Grace, and took on the surname Lawrence. They were supported by Sarah Tawell, though she had to go to court in order to reclaim John’s assets. He had never formally completed a will, and by default his money was all forfeited to the Crown. Eventually Sarah managed to get the money back, but in the meantime she and her two children went to live with John’s brother William in Essex. This led in 1851 to William’s son Samuel marrying Eliza Cutforth, the daughter from Sarah’s first marriage. The Tawell family did their best to fade into obscurity and to shake of the shame of their dead patriarch.

The Australian press labeled John as “Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde” for his public philanthropy and private “depravity”. The Quakers did their level best to disassociate themselves from him, pointing out that he had never been formally readmitted to the Society. The story never got the fame of other infamous Victorian murders, once the novelty of the use of the telegraph had worn off. You can still see that very telegraph on display in the London Science Museum. An unassuming mechanism of wood and brass that brought the weight of justice down on a murderer’s head, and in so doing changed the world forever.

Pictures via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] It’s possible that the murder of Sir Theodosius Boughten by his brother-in-law Captain John Donnelly in 1780 was committed using cyanide, and if so that would be the first such case. However there were no tests at the time to detect the poison, so it’s simply the most likely of the several he could have used.

[2] Sir Fitzroy was later tormented with the nickname “Apple-pip Kelly” for his argument in this case.