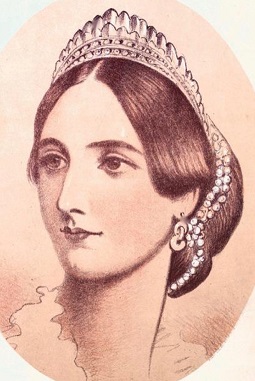

Lady Jane Wilde (alias Speranza), Writer

“Great people” rarely come from a vacuum. Though genius can blossom on the hardest ground, it most often finds root on the fertile soil of supportive and almost-equally talented family members. Sadly however, the bright light of genius often leads to those family members being thrown into the shade. One such case was Oscar Wilde’s mother, who was once the famous Irish writer “Speranza”: Lady Jane Wilde.

Jane Francesca Agnes Elgee was born in County Wexford in 1821. Her father Charles was a solicitor, but he died when Jane was only three years old. It was a bad year for the family of his widow Sarah, as her sister (who was married to the writer Charles Maturin) was widowed the same year. As a result Jane was denied even the basic formal schooling that was available to young women at the time. This didn’t really slow her down though, as she had a ferociously studious nature that say her spend her teenage year voraciously absorbing all available knowledge from any book she could get her hands on. Languages were one of her major passions, and she had learned ten European languages by the time she was eighteen years old.

Jane’s family were staunchly Unionist, coming as they did from English stock. Jane herself was disinterested in national politics until 1845, when she saw the funeral of Thomas Davis and heard that he was a poet. Curious, she looked into his writings and discovered a new world. Davis is often credited as being the writer who inspired the Irish nationalist movement of the 19th century, despite his death at the age of 30 from scarlet fever. A Protestant himself, he espoused an idea of Irishness that ignored ethnic or religious identity in favour of an inclusive nationalism. Jane was captivated by the ideas and ideals that Davis promoted, and became a fervent convert.

Jane wrote a passionate letter (which she signed “John Fansworth Ellis” to The Nation, a nationalist newspaper. The letter caught the eye of editor Charles Gavan Duffy, and he wrote back offering “John Ellis” work. And just like that, Jane’s writing career began. Like most of the writers in the paper she had to choose a pen name. Inspired perhaps by an Italian great-grandfather and by the perception of Italy as the birthplace of nationalism she chose the name “Speranza”; the Italian word for hope. At first she used her expertise with languages to produce translations of continental revolutionary poems, but she soon began contributing her own poems as well.

The Nation was by its nature a controversial paper producing controversial content, and Speranza was soon known as one of its most fiery writers. Duffy became an ardent admirer, and described her as “the spirit of Irish liberty embodied in a stately and beautiful woman”. The famine in 1847 was particularly inspirational, as she wrote eloquently about the millions dying in Ireland while “stately ships to bear our food away” arrived daily. Her most popular poem was The Brothers, a lament for the two leaders of the 1798 Rising that was turned into a popular Dublin street ballad.

Pale martyrs, ye may cease, your days are numbered;

Next noon your sun of life goes down;

One day between the sentence and the scaffold

One day between the torture and the crown!A hymn of joy is rising from creation;

Bright the azure of the glorious summer sky;

But human hearts weep sore in lamentation,

For the Brothers are led forth to die.

One particularly noteworthy piece of writing that Speranza produced for The Nation was Jacta Alea Est (”The Die Is Cast”), an unsigned editorial that called for Ireland to join in the wave of revolutions that were sweeping across Europe prompted by the deposing of the French monarchy and the forced resignation of the conservative German minister Metternich. The article was one of the grounds given for the arrest of Charles Gavan Duffy for sedition and the suppression of The Nation. When Duffy denied having written the article Jane stood up in court and took credit for it. Perhaps luckily for her the judge seems to have decided to ignore her. This took place against the backdrop of the Young Irelander “rebellion” of 1848, which was in truth more a single riot than a full-blown rising.

The Nation was revived later in 1848 and Jane resumed writing for it. She also began publishing translations of European novels, Sidonia the Sorceress by William Mannheim and The Glacier Land by Alexander Dumas. By now she had also begun to absorb the ideals of early feminism, writing about women:

At present they have neither dignity nor position. All avenues to wealth and rank are closed to them. The state takes no notice of their existence except to injure them by its laws.

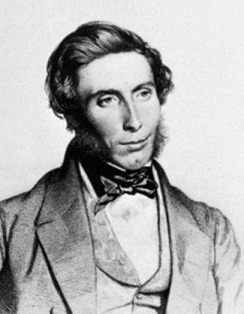

Yet she was not so liberated as to throw men off entirely, and in 1851 she married the surgeon and writer William Wilde. He was one of Dublin’s most notable eye doctors, and two years after their marriage he was appointed “Oculist-in-ordinary” to Queen Victoria. He was also a writer (though of a different stripe) as he was the editor of the Dublin General of Medical Science and wrote several articles for it. Jane may have been attracted by his tales of travel, as he had journeyed to the Middle East in his twenties. She was under no illusions as to his prior character, as he had several illegitimate children he openly acknowledged. One, Henry Wilson, was thirteen years old at the time of their wedding. He also had two daughters, aged four and two years old. William provided for the children and even took Henry on as an assistant several years later when he had grown up and completed his medical training.

Jane and William had their first child in 1852 and named him William after his father (though he was always known as Willie). Two years later they had a second son, who they decided to name Oscar. And two years after that they had a daughter, who they named Isola. Throughout this time Jane continued to write poetry, and became a popular figure due to her nationalist stance and her eloquent writing. In 1864 she had a book of poems published. That was the same year that Jane wound up in court, due to a letter she had written to the father of Mary Travers.

Mary Travers was the daughter of a friend of William, and became his patient in 1854 due to some trouble she had with her hearing. She was nineteen years old at the time. Through their treatment she and William struck up a friendship and Mary became a frequent guest at the Wilde home. It’s been suggested that Jane brought her into their home in this way in an effort to discourage her husband from having an affair with her. But the exact details of what went on between the trio are murky however, obscured by contradictory testimony. According to Jane and William, this was a friendship with a young girl who had a crush on William that soon spiraled into obsession. If this is true, he was definitely guilty of encouraging her through the passionate correspondence the pair had. He may have actually had an affair with her, and then tired of her. But according to Mary, the relationship was a far darker one. She claimed that after some mutual flirtation over the years, in 1862 she was rendered unconscious by William while he was examining her in his surgery and he raped her.

There are contradictions between Mary’s account and her behaviour that led some to dismess her claim, but there is also some strong supporting evidence in the change of tone in the letters between her and William. He urged her “Do keep quiet, dear, for a while and see what is best to be done.” Mary didn’t tell anyone about what had happened, but she did seem to become intent on self-harm during 1863. In January after a ferocious argument Mary stormed out of William’s study, obtained a bottle of laudanum large enough for an overdose, and then returned and drank it in front of him. William accused her of trying to frame her for poisoning him, but he saved her life by taking her to a pharmacy and getting an emetic which he made her drink. On another occasion Mary sent Jane a faked death notice for herself. In August Mary called on Jane, and Jane refused to see her. Mary then sent her one of William’s more passionate letters, only to have it returned with a cover note saying that Jane had no interest in the subject. This sent Mary into a rage.

Mary wrote a pamphlet, called Florence Boyle Price, or A Warning. It was the story of a girl named Florence who was put under with chloroform by the villainous “Dr Quilp” and raped, and who was then given short shrift by “Mrs Quilp” when she tried to appeal to her. Leaving no doubt as to her target, she signed the pamphlets “Speranza”. Mary then sent copies of the pamphlet to the Wildes’ friends, and paid to have extracts published in the Dublin Weekly Advertiser. She also began badgering William for money, implying that the harassment would stop if he paid up. William refused.

In 1864 William was knighted for his services to medicine and to the Irish census, which infuriated Mary. She stepped up her campaign and in April of 1864 it reached its peak. William and Jane arrived at the Metropolitan Hall in Abbey Street where William was to give a public lecture. There they found five newsboys selling copies of Florence Boyle Price for a penny each. They were wrapped in a flysheet that included extracts from William’s letters to Mary and a header explicitly naming him. This was too much for Jane and she left for Bray with Isola. There a boy called to the door selling copies of the pamphlets. When the young Isola began asking questions Jane seized the pamphlets from the boy. As a result Mary had her summonsed in Bray Court for “theft and threatening behaviour”. This provoked Jane to write an angry letter to Mary’s father. In it she referred to Mary’s “disreputable conduct” and that she “consorted with the low newspaper boys at Bray”. She also referred to Mary’s demand for money from William as the “wages of disgrace”. Mary managed to get hold of the letter, and gave it to her solicitor who used it to sue Jane for libel. Since the law at the time held a husband responsible for his wife’s actions, William was included in the suit. The trial was set for December of 1864.

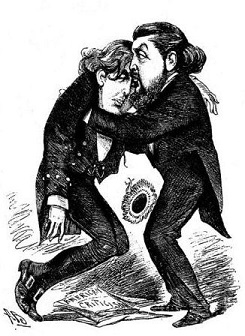

The court case was, naturally, a public sensation. In an intriguing bit of irony Mary was represented in court by Sir Isaac Butt. He was the counsel who had defended Gavan Duffy back in 1848 when Jane had stood up to claim responsibility for Jacta Alea Est. There had been gossip at the time that Isaac and Jane had an affair, and that Isaac’s wife had caught them in the act. If that was so, he did not allow sentimentality to taint his treatment of her in court where he portrayed her during questioning as a pitiless wife sacrificing a young woman to protect her husband’s reputation. Jane was not perturbed, and claimed that Mary was a woman driven off the rails by having been socially slighted who had concocted the whole affair to get back at her. When she was accused of implying that Mary was a prostitute (her ambiguous wording in the letter coming back to haunt her) she denied it. It was a masterful performance, though her side was fatally undermined when her husband refused to take the dock.

Mary’s side were equally undermined, but this was due to the dictates of their client. Mary insisted that they make her alleged rape by Sir William Wilde a central part of their case, even though it had no relevance to the libel charge. It did put her accusations out into the public domain directly (and in a way that shielded her from a libel charge of her own), but it also weakened her case. In his summing up the judge was deeply unsympathetic, pointing out the inconsistencies in her charges and asking why she had not come forward at the time. Plus ca change. It was probably due to the effect of this that though the jury found in Mary’s favour, they only granted her damages of a single farthing. [1] Since they did award Mary costs, the end result was the Wildes having to pay out £2000. But it was the damage to both Mary and Sir William’s reputation that was to prove far more severe in the long run. Jane, however, came out of the affair with her reputation enhanced; as both the papers and popular opinion were very much on her side.

In 1867 tragedy struck the Wilde family. Little Isola, the darling of her parents and her brothers, died of a fever just two months before her tenth birthday. All of the family were heartbroken, and her brother Oscar (who had adored her) was especially affected. For years he was a frequent visitor to her grave, and he carried a lock of her hair in an envelope until the day he died. He would go on to write one of his most famous poems, Requiscat, about her. Jane was also heartbroken, though she took comfort in her two sons. Sadly Isola was not the only daughter William Wilde would lose to tragedy. In 1871 his daughters Emily and Mary (who were by now in their 20s) attended a party in County Monaghan. As Emily was dancing her dress trailed into a fireplace, and the dry crinoline skirt went up in flames. Mary rushed to rescue her sister, only for her own dress to also catch light. Both were severely burned, and died of their injuries a few weeks later. [2]

By the 1870s it had become Jane’s tradition to host a Saturday salon in her house, in the Parisian style. This proved to the advantage of Willie and Oscar when they began to attend Trinity university, as their professors were all attendants at the event. It did mean that much was expected of them, though both proved more than able to the task and won many prizes throughout their careers. In his third year Oscar won a scholarship to Oxford, and so Jane had to bid him farewell as he set off to begin his legendary career. Willie stayed in Dublin and studied law, though he never practiced as a lawyer. During this time Jane and Sir William were practically separated, as he lived mostly in Connemara while she stayed in Dublin. He had never recovered from the loss of his three daughters, and he died in 1876 aged only 61.

The death of Sir William had a dramatic effect on Jane’s life. Like many at the time he had wielded his name and reputation to keep the creditors from the door, and Jane was shocked to learn that they had been living beyond his means for years. She was left on the edge of bankruptcy, and was left to rely on her writing and on Willie for support. Oscar graduated from Oxford in 1878, and he moved back to Dublin. In 1879 Jane and Willie both decided that London offered them better scope as writers, so they moved to the English capital. Oscar soon followed. Over the next few years Oscar’s star rose and rose, while Willie’s guttered and fell. He was a talented writer, and could have been a great success, but he was also a crippling alcoholic.

Jane trod a middle path between her two sons. Already an established writer, she had no problem selling articles to the Pall Mall Gazette and many other prestigious magazines. She contributed some writings of Irish folk tales to the Celtic revival anthologies created by WB Yeats. In addition, she wrote several books of her own. These included Ancient legends, mystic charms, and superstitions of Ireland based on her husband’s research into Irish folklore. She also wrote a book called Social Studies giving her views on the shift in society that saw laws passed to grant women property rights after marriage (where previously their husband had owned everything) and to give women the right to a university education alongside men. Jane greeted these moves with delight. In her book she wrote:

We have now traced the history of women from Paradise to the nineteenth century and have heard nothing through the long roll of the ages but the clank of their fetters.

Yet she remained optimistic, and declared:

Now, for the first time in the history of the world, a path is opening to female intellect, energy and talent, and, henceforth, women, perhaps, may lead in the learned professions, take their part in home government, form ministries to organise the code of female rights, and claim the highest university honours in rivalry with men.

By the 1890s Oscar was now hailed as one of the great writers of the age, while Willie’s life was in utter disarry. In 1891 he made an ill-advised marriage to an American widow named Miriam Leslie and moved to New York. The marriage lasted less than a year, as Miriam had little patience with his drinking and infidelity. He returned to London, where he became more and more jealous of Oscar’s success. Oscar was equally unhappy with Willie, as though he was happy to lend his brother money he was angry when he found out that Willie had also been sponging off Jane. Worse was to follow, as in 1894 Willie married his lover Sophie Lees when she thought she was pregnant. (She was not.) The penniless couple moved in with Jane, straining her even further. She was in her seventies, and ill-suited to playing host to her drunken son and his wife. In 1895 Sophie actually became pregnant (with what would be her daughter, Dolly Wilde). [3] But before the baby was born, Oscar would fall meteorically from grace.

The story of Oscar Wilde’s infamous libel trial, and how it ended with him being charged with criminal homosexuality, is a well-known one. Suffice to say that his mother was fatally emboldened by her own success in court due to her popularity, and thought that the same victory would come to Oscar. After he lost his libel trial (just as she had), she was the sole voice who advised him not to flee to France to avoid prosecution. The guilt she must have felt when he was arrested and was sentenced to two years of hard labour for “homosexual behaviour” is hard to imagine. The stress had its toll, in in January of 1896 she fell ill with bronchitis. Knowing that she was dying she appealed to be allowed to visit Oscar in jail, but her appeal was refused. She died on the 3rd of February.It was later said that her ghost appeared in Oscar’s cell the moment she died.

Both Jane and Willie were penniless when she died, so her funeral was paid for out of Oscar’s estate. He could not, of course, attend. Nor could he afford a tombstone, so the great “Speranza” was instead buried in an unmarked grave in Kensal Green cemetery. She was at least fondly remembered, as one obituary described her as “a brilliant woman who had contributed much to literature and social life in England and Ireland”. Her two sons would soon follow her. Willie died in 1899, his health ruined by alcoholism. Oscar had ruptured an eardrum in prison and after he moved to Paris on his release an infection spiralled into meningitis. He died in November of 1900. It was devotees of his work who raised a monument to Jane in Kensal Green in 1999. A similar monument to Jane is in Dublin, at the grave of Sir William Wilde. It remembers the fiery Speranza, who once dreamed of an Ireland made free.

I had dreams of a future of glory

For this fair motherland of mine,

When knowledge would bring with its splendours

The Human more near the Divine.

And as flash follows flash on the mountains,

When lightnings and thunders are hurled,

So would throb in electrical union

Her soul with the soul of the world.”

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] A traditional thing to do in libel cases in British law at the time where the jury feel that though the accused is technically guilty of libel, the result caused no substantial harm to the plaintiff’s reputation.

[2] Emily and Mary’s mother has always been anonymous, though she was apparently involved in their lives and was even at the party where they died.

[3] Who would go on to become one of the lovers of Natalie Clifford Barney.