Louis Aragon, Surrealist Poet and Communist

When Louis Aragon died, the New York Times obituary ended with the line: “Even those who disagreed with his politics admired his talents as a poet and as a novelist.” Separating an artist from their beliefs is difficult at best and woefully misguided at worst, especially when somebody has so thoroughly embraced and publicised their beliefs the way Louis did. But then again, few people had quite the impact on a country’s literary trajectory as he did, either.

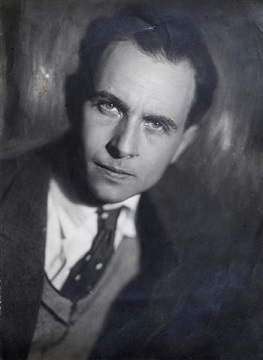

Louis Aragon was probably born on the 3rd of October 1897, probably in Paris. The uncertainty comes from the irregular circumstances of his birth; his mother (Marguérite Toucas-Masillon) was a teenager while his father (Louis Andrieux) was a married career politician in his late fifties. Andrieux had no intention of acknowledging his illegitimate son while Marguérite’s family had no wish for the scandal that would descend on her if the truth was known.

So the story was given out that Louis had been adopted by Claire Toucas-Massilon (his grandmother) with his actual mother acting as the elder of his two sisters. His father (who pretended to just be his godfather) gave him his own first name and the surname of “Aragon” after where he had been stationed as an ambassador in Spain. It was about the only thing Louis ever got from his “real” father, even after he learned the truth many years later.

Actually, that may not be entirely fair. Young Louis did attend some fairly exclusive (and expensive) schools, including the Lycée Carnot to the west of Paris. This might have been his “godfather” applying some influence on his behalf. He was a writer from an early age and wrote several poems and short stories throughout his teenage years. World War I broke out just as he was finishing school, which may have been what led him to decide to study medicine.

He did so at the military hospital of Val-de-Grâce, and that was where he first met André Breton. The two men became close friends, bonding through the shared trauma of the horror of war. In particular the reconstructive surgery that was developed at the hospital to try to rebuild faces and bodies destroyed by the horrific new weapons deployed at the Front had a massive influence on the pair’s perception of the human form and their later work.

Since you sleep and their laughter

Cannot disturb your sleep

Allow me to say before all

The sun is the sun.

…

Because a dead woman is a queen

To her child.

– La Mot (“The Word”)

Inevitably the time came for Louis to go to the Front himself, a trip from which his mother Marguérite did not think he would return. So she told him the truth about his parentage though she made him promise to keep it a secret. That was a promise he would keep until her death in 1942, after which he wrote about his sorrow that he had never been able to acknowledge her as his mother. (He did confront Louis Andrieux, but Andrieux refused to acknowledge his son right up until he died in 1931.) It was with this revelation in his head that Louis went to serve on the Western Front of the Great War.

Somewhat to his own surprise he was one of those who made it through that meat-grinder and returned home two years later. But, like most of those who returned from the trenches he was never quite the same again.

“Dada” was a movement born out of that change, a realisation that it was the imperialist social norms and unquestioning obedience to authority which had led to the horrors of the last war where millions died at the whim of their leaders. (The flu epidemic which followed the war and killed millions more only served to underline the insignificance of human endeavor, in the eyes of the movement.) Dada was, in the words of Hans Richter, “anti-art”; a rejection of what had come before. To a young writer like Louis it was hugely influential and his first novel, Anicet, proudly proclaimed itself a “Dadaist novel”.

Louis had written the novel in the trenches, during action which had seen him constantly barraged by shellfire (he was reportedly once buried by explosions three times in one day) and where he had earned the Croix de Guerre for his heroism in rescuing injured soldiers. The novel was an escape from the reality of the war, and indeed an escape from reality itself. The hero, Anicet, purposefully refuses to engage with the world around him as he refuses to recognise its reality.

He encounters “non-characters” based on the fellow artists Louis knew or admired (such as Breton, Picasso and Charlie Chaplin); and winds up drawn into the underworld by the mysterious Mirabelle. (Mirabelle was based on the actress Musidora, a heroine of pulpy pre-war action shorts where she played the leader of a gang of thieves.) Anicet is to this day hailed as the “great Dadaist novel”, and it immediately put young Louis Aragon on the map as one of the leading lights of the new movement.

Where Louis was going to lead the movement became apparent the following year, as he and André Breton began to look beyond Dada and into the future of art. Rejecting reality could only get you so far; now they sought to reshape the real, and to create something new. André had become interested in psychology after the war as he worked with shell-shocked patients, and the new idea of dreams as a doorway into the subconscious particularly intrigued him. It was this direction that he, Louis and their new partner Philippe Soupault took things in. To describe this new art of the subconscious they adopted a term coined by the poet Guillame Apollinaire, who had died in the war: Surrealism.

“Surrealism, n. Pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought. Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation.”

– André Breton’s definition of Surrealism.

André, Philippe and Louis were not the only ones to take up the baton of Apollinaire’s philosophy. In 1924, for example, the poet Yvan Goll published a magazine called Surréalisme. This enraged André who considered himself the “leader” of Surrealism and resulted in a meeting that soon degenerated into a literal fist-fight. It wasn’t just surrealism’s future that they laboured over though; they also sought to demonstrate the inevitability of their movement by claiming previous writers as surrealists.

Louis was a particular fan of Lewis Carroll, for example, and translated several of his books into French. He also produced his own original works during this time, of course. The most famous of these was Le Paysan de Paris (”The Peasant of Paris”), which was originally serialized in Philippe’s magazine Revue européenne. On the surface it seems like a simple travelogue describing the mundane details of two places in Paris, a park and a street in the opera district (as they would be seen by a peasant visiting the city). But the wonder of those places to the outsider is enhanced by visualising them as wonders to anyone – prostitutes transforming into sirens, for example.

Thus Louis evokes places that he describes as “the true sanctuaries of a cult of the ephemeral, the ghostly landscape of damnable pleasures and professions. Places that yesterday were incomprehensible, and that tomorrow will never know.”

Around the same time as he was helping to establish Surrealism, Louis became involved with an even bigger influence on his life – Communism. In January of 1927 he joined the French Communist Party along with the majority of his fellow Surrealists. Mostly they were only partially committed to the political ideals of the party, but Louis was a true believer. His communist ideology informed most of his work from then on.

Of particular note is Traité du style (”A Treatise On Style”), which he wrote in the summer of 1927 and which was inspired by the execution in America of the anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti on trumped up charges. In it he argued that Surrealism without a deeper meaning was just tristes imbécillités – “sad imbecilities”. In other words, his politics were now to him an integral and necessary part of his writing. And another integral part of his writing was about to appear.

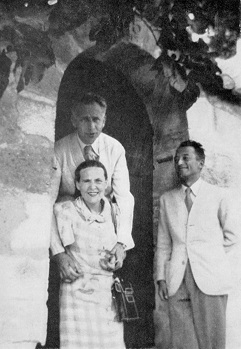

Since 1926 Louis had been in a relationship with Nancy Cunard, an English heiress who had moved to Paris years earlier and who was involved in the Surrealist movement. They broke up in 1928 (after he found out that she was cheating on him with the jazz musician Henry Crowder); and Louis met Elsa Triolet. Elsa had been born in Russia as Ella Kagan, the daughter of a well-off Jewish family.

She had been involved in revolutionary circles in Russia since she was quite young, but in 1919 she had married a Frenchman named André Triolet and emigrated to Paris. She left André in 1921 and had spent several years wandering through Europe (including a return to Moscow as well as visits to London and Berlin) before returning to Paris. She was a writer in her own right with three published novels, and was a friend of several surrealists (including Marcel Duchamp). And then in 1928, at the cafe-nightclub La Coupole (a popular haven for artists of all stripes) she met Louis Aragon. In her novels Elsa had written of an enduring loneliness, a gap in her life that (despite her friends, family and first husband) she had never been able to fill.

In Louis she found what she had been looking for all those years. For his part Louis found a muse, but more importantly he found a partner and a friend. It would be another ten years until they were married, but in that cafe in 1928 began a relationship that would endure for the rest of their lives.

The late 1920s were a tumultuous time in Communism. Prior to this dissent had been tolerated among the politicians running the country, and Leon Trotsky had led the “United Opposition”. Gradually though Stalin began to crack down on those who opposed him, and eventually Trotsky was exiled from the USSR. This led to deep divisions among Communists outside the USSR, including among the members of the Surrealists.

Louis remained loyal to the USSR, which was one of the many things that led to a break in his friendship with André Breton. In fact Elsa’s Russian connections paved the way for Louis to visit the USSR in 1930, and like most Western visitors he was given a VIP treatment and a carefully curated experience that led him to come back praising the country. Inspired by the trip he wrote a poem, La Front Rouge (”Red Front”). The poem caught the attention of the authorities, and he was arrested and charged with “provocation to murder for the purpose of anarchist propaganda”.

You are the armed conscience of the proletariat

You know while you carry death

To what admirable life you are making a road

Each of your blows is a diamond which falls

Each of your steps a fire which purifies

The lightning of your guns makes ordure recoil.

– La Front Rouge, as translated by ee cummings

Louis was charged under the Lois scélérates (”Rogue Laws”), laws passed in France in 1894 and only repealed in 1992 which gave the authorities wide-ranging powers to suppress “anarchists”. That they dug out such an old law to use against him shows perhaps how seriously the “Communist threat” was. Despite their quarrel, André Breton started a petition to have the charges dropped which proved a lightning rod for opinion among the writers of Paris. Almost everybody signed it, but a few people refused. Among the more notable was the writer André Gide, who was actually a Communist sympathizer, and the “Unanimist” socialist writer Jules Romain. Both gave the same justification – a poem should mean something, and so it should be considered only right for it to provoke prosecution. Either way it didn’t matter, as Louis was exonerated at trial.

The later 1930s were defined by the rising tide of fascism in Europe, and Louis was one of those who stood firmly against it. Given the fact that Elsa was Jewish (and there’s speculation that Louis’s mother’s family may also have been converted Jews), it’s not surprising that he was staunchly anti-Nazi. He worked as a journalist for the socialist newspaper L’Humanité, and wrote for them against Mussolini and the Spanish Fascists.

He also was the co-editor of Commune, the newsletter of the Association des Écrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires, and in 1937 he was asked by the French Communist Party to create a newspaper for them. Standing in opposition to Paris-Soir (a popular right-wing newspaper) the new paper was simply called Ce-Soir (”Tonight”). The high quality of writers he could draw on meant that the paper was swiftly able to establish a readership.

By 1939 it had established a readership of 260,000 through articles that were consistently pro-USSR and anti-Nazi. That was the year that Louis married Elsa, and his love for her was the other consistent theme of his poems at that time. But then in August of 1939 a thunderbolt fell. The USSR and Germany signed a pact of non-aggression. Perhaps for the first time, Louis’ faith wavered. He wrote an editorial where he hailed the pact as “a triumph for peace”, but he also called on France and Germany to sign their own pacts with the Russians and declared his continuing opposition to the Nazis.

This mixed response wasn’t enough for the French authorities though. Their response to the pact was to immediately shut down all Communist publications in France, and both Ce-Soir and L’Humanité were among those banned. Louis took refuge in the Chilean embassy for a few days for fear of being arrested, but soon more important matters took precedence. War was about to break out.

When the war did begin in September of 1939, Louis was drafted into the French army. Specifically, given his previous experience, he was enlisted into the medical corp, attached to a tank division, and sent to the Front for what was derided in the press at the time as the “Phony War”. Germany’s invasion of Poland had prompted France and Britain to declare against them, but neither side was initially willing to engage in direct conflict. There was an initial French push, but after it was beaten back they decided to fortify and wait for a German assault. And wait.

And then in May of 1940 the Germans came, fiercer and faster than the French had believed possible. In one of the first action of the “Battle of France” Louis’ division were defeated and he was captured, but he managed to lead thirty-sex men in an escape back across French lines. That, combined with his later bravery in rescuing men under fire, was enough to earn him a second Croix de Guerre. But no matter how heroic its soldiers were, France could not hold out against this sustained attack. On the 24th June, after less than six weeks, the French government surrendered. The Battle of France had been lost.

In theory occupied France was ruled by Prime Minister Philippe Pétain. In practice it was the German Ambassador, Otto Abetz, who was calling the shots. He drew up lists of authors who were banned under the new regime, and unsurprisingly Louis was on the list. Elsa too was in danger, as her Jewish background meant that laws passed in September of 1940 deprived her of her civil rights. So they went underground, joining the Resistance.

They headed to the south of France, where together they established a network of writers affiliated to the Comité national des écrivains. In 1941 the writers Jean Bruller and Pierre de Lescure set up Les Éditions de Minuit (”The Midnight Press”), and they published a collection of patriotic poems by Louis called Le Musée Grévin (after a waxwork museum in Paris). He used the pseudonym François la colère (”The Anger of France”). (Another pseudonym he used was Le Témoin des Martyrs – “The Witness Of Martyrs”.) In addition he and Elsa produced underground newspapers like Les Etoiles (”The Stars”) which were distributed throughout France in secret. Les Etoiles took its name from the organisation of the writers in the resistance – they were organised into cells of five that they called “stars”.

Louis and Elsa managed to avoid capture until the liberation of France, when they were hailed as heroes. Elsa’s novel about the liberation, Le premier accroc coûte 200 francs [1] won the Prix Goncourt (France’s most prestigious literary prize) in 1944. She was the first woman to ever win the award. Louis published a collection of his resistance poetry and a series of novels (called Les Communistes) portraying the history of France during the war.

After six volumes he’d only made it as far as the defeat and occupation of France and decided to end it there. He became a leading figure in the Communist Party in France as the writer’s organisation he had created during the Resistance became now a political one. In the ten years after the Liberation he was heavily involved in driving policy (such as the French party’s response to the Tito/Stalin feud). He did face some backlash though for his “anti-Stalinism”, especially when the man died in 1953. It’s been suggested that Elsa’s Russian relatives may have made him and her aware of the negative impacts Stalin’s rule had for the common people. Then in 1955 Louis wrote a poem named Strophes pour se souvenir which would become, under the name of L’Affiche rouge, one of his most famous works.

There were twenty-three of them when the guns flowered

Twenty-three who gave their hearts before it was time,

Twenty-three foreigners and yet our brothers

Twenty-three in love with life to the point of losing it

Twenty-three who cried “France!” as they fell.

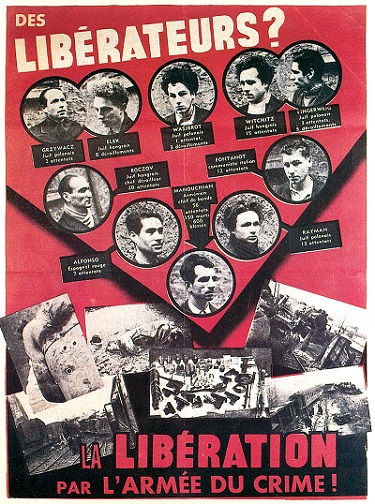

L’Affiche rouge (”The Red Poster”) was the title given to the poem by Léo Ferré when he set it to music in 1961 as part of his album Les Chansons d’Aragon (which, as the name suggests, was all songs setting poems by Louis to music). The poem was written to go along with a memorial to twenty-three Resistance fighters known as the Manouchian Group who had been executed in 1944.

Louis’ poem was partially based on the last letter that the leader of the group, a French-Armenian poet named Missak Manouchian, wrote to his wife Mélinée. Since the fighters had been foreigners the Vichy regime had tried to use them as part of a propaganda campaign to discredit the Resistance as a foreign movement. They created a red poster (L’Affiche Rouge) that had photos of the men along with their “foreign” names and alleged crimes. (For example, some of the had assassinated an SS general.) The campaign backfired badly; the posters were frequently defaced with the words MORTS POUR LA FRANCE – “Died For France”, the traditional phrase used on monuments to French veterans.

1956 was a divisive year in the international Communist movement. A strike by Polish workers in June against their Communist government seeking better working conditions was both a sign of the post-Stalin cracks in the authority of Russia, and a wake-up call to many Western Communists that life behind the Iron Curtain might not be the “Worker’s Paradise” that some of them thought it was. The protests soon turned into a worker’s uprising that the government beat down, but aware of their position they then negotiated some concessions from the Soviets that allowed them to improve conditions for their workers.

As a result protests began in Hungary, led by writers and students hoping for similar reforms. The government resisted, and the protests escalated into riots which became a full-scale revolution. The revolution overthrew the government and installed a new one; but when they began making moves to exit the Warsaw Pact and declare neutrality then the Russians sent in their troops. The “Revolutionary Workers’-Peasants’ Government of Hungary” was replaced by the “Hungarian Revolutionary Worker-Peasant Government” in a bloody military action.

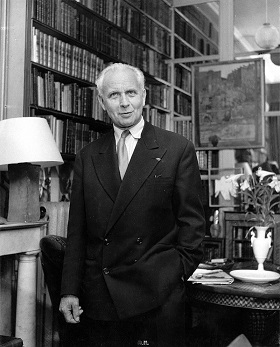

The events in Hungary were condemned around the world, and the hypocrisy in the actions of the Soviets divided many Western Communist parties. France was no exception. Arguments and division led to the end of the Comité national des écrivains, and many left the Communist party. Louis Aragon stayed, but he used his position as the editor of Les Lettres françaises (the literary supplement of L’Humanité) to denounce Soviet authoritarianism. His prestige meant that he could get away with publishing Soviet dissidents and condemning the trials of intellectuals. But he still remained loyal to the ideals of the USSR, at least, and he was the CEO of a publishing house that translated mostly Soviet literature for release in France.

Elsa had been even more actively anti-Stalinist than Louis, publicly denouncing the behaviour of the Soviets in 1956 and translating the works of many banned Russian dissidents. Still, the two remained together and devoted to each other throughout the 1960s. That doesn’t mean they were faithful to each other, of course. Louis (who was bisexual) in particular had many male lovers, though he kept everything discreet for Elsa’s sake. Elsa died of a heart attack in 1970 at the age of 73. Louis was devastated.

As a result (and due to his own advanced age) he stepped back from politics and editing, and devoted himself to writing entirely. He re-embraced the artistic connection of his youth, and possibly his most famous work from that period was his novel/biography about the painter Henri Matisse. After that he returned to his Surrealist roots, as well as more openly displaying his sexuality by attending Parisian gay pride parades in a pink convertible. He died on Christmas Eve in 1982 and was buried next to Elsa in a private park on his property. His career was almost a history of French literary traditions throughout the 20th century, and to this day it remains popular and influential.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] “The first tear costs 200 francs.” A sentence which was posted in billiard halls in France to inform people of the fine that they would face for tearing the felt on a table; but more importantly also the code phrase used by the BBC to tell the resistance that the D-Day landings had begun.