Nell Gwyn, the People’s Harlot

When Charles II was restored to the throne of England in 1660, it was clear that things were not going to be the same as they had been before the revolution that had toppled his father from the throne and executed him. Fortunately for “the Merry Monarch”, he was smart enough to recognise this and avoid the mistake of trying to turn the clock back that would lead to disaster for the Bourbons of France 150 years later. The people had tasted power, so Charles set out to become the people’s king. And for the people one of the most potent symbols of that connection was the woman from their ranks who shared his bed. Royal affairs had previously been kept discreet, but Charles didn’t hide his extra-marital affairs. He flaunted them. And none of his mistresses became more famous, or more popular, than Nell Gwyn.

Nell (short for Eleanor) was ten years old when Charles was restored to the throne, and by her own later admission she was serving drinks in a brothel run by her mother. (That story did carry the qualifier that serving drinks was all she did, which seems to have been true as her later enemies would certainly have dug up any evidence to the contrary.) Her mother Ellen was in her thirties at the time, a born and bred Londoner. Nell’s father is harder to pin down – he’s often described as a Welsh soldier named Thomas Gwyn (or Gywnne, or Guinne) who fought for the Royalists and died in a debtor’s prison in Oxford in 1661, but that’s pieced together from fragments here and there. Where Nell was born is also disputed – London is the most obvious choice, but it’s also been claimed that she was born in Oxford (where her father was imprisoned). The most popular tradition has it that she was born in Hereford, in the west of England, and that her mother returned to London after separating from her husband. With the sparse record-keeping of the wartime years, it’s impossible to know for sure.

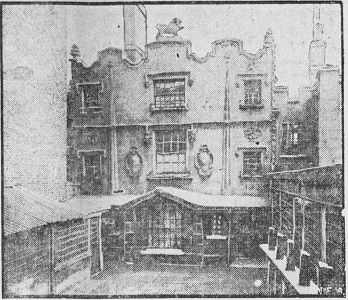

In 1662 someone named Duncan – possibly an officer in the guards named Robert Duncan – took notice of Nell and began a relationship with her. (Which is a bit disturbing, given that she was still only twelve years old at the time.) He moved her out of her mother’s house and into private rooms. He might also have been the one who got her a job in the new theatre on Drury Lane, though it’s more likely it was her mother’s friendship with the woman who was given the concessions license there, Molly Meggs. All theatres had been closed and banned as immoral during the reign of Parliament, but Charles had ordered them reopened. Nell’s job was to sell oranges (a popular snack) to the crowd during performances, a job that generally required the wit and forwardness to banter with potential customers to entice sales. It also required the girls to act as messengers from wealthy men who wished to meet with the actresses backstage, and it was probably while carrying one of those messages that Nell caught the eye of Thomas Killigrew.

Killigrew had been a playwright before the war, and was one of those who had fled the country with the future Charles II in 1647. He had stood by the prince and king during his time on the continent, and according to some stories had acted as the court in exile’s chief spymaster as well as his court jester. One of his rewards for that service was one of the first licenses to establish a theatre company once they were made legal again. It was in part due to his influence that the new law included one key change. It made it legal for the first time in England for women to act on stage. As a result Killigrew was for on the lookout for female acting talent, and in this chirpy and witty young orange-girl he decided that he had found it. He sent Nell to a school for acting that he had established and in March of 1665, about a month after her 15th birthday, she made her debut on stage.

Nell Gwyn took to acting like a fish to water. At the time the norm was for short play runs and variety in order to keep drawing people to see new plays, and so it wouldn’t have been uncommon for Nell to be in a new play each week. It soon became clear that her strength was in comedy, especially in parts that combined witty banter with physical humour. She was paired up with veteran actor Charles Hart, a man who had been imprisoned for defying Cromwell’s ban on theatrical performances, and the two soon made a highly successful partnership on stage while becoming lovers off stage. She became a favourite of both the crowd and the playwrights, with Thomas Dryden writing plays specifically in order to make best use of her talents. The diarist Samuel Pepys described her as “pretty, witty Nell” and was a huge fan of her performances.

He wasn’t the only fan of her, and soon the requests for assignations began coming in. At the time the core of theatre-goers were pleasure-loving aristocrats, and it was pretty much accepted that many of them were in search of mistresses among the actresses. The Great Plague in 1665 (leading the theatres to relocate to Oxford for a while) and the Great Fire in 1666 led to a delay in Nell attracting that type of attention, but early in 1667 she had a brief affair with Charles Sackville, heir to the earldoms of both Dorset and Middlesex. Sackville was popular despite being a notorious rake, but the theatre-going public were not happy when he swept up Nell in April and took her away from the stage right around the beginning of the season. Their affair was relatively brief though, and by August she was acting once again.

The Duke of Buckingham, a man who had a fairly stormy relationship with the King, was the one who started the plan to make Nell the mistress of the king. At the time the king’s primary mistress was Barbara Palmer, who happened to bye Buckingham’s cousin. The two didn’t really get on though, and Barbara was notorious for using her influence at court – to the extent that she was regarded by many as the “true Queen”. She had given Charles five children by now though, and Buckingham was hopeful that she could be displaced as the primary object of his affections.

Nell, practical as ever, was fully on board with this plan. According to legend, she smoothed her path by getting her friend the writer (and alleged spy) Aphra Behn to deal with an actress named Moll Davis who was currently sleeping with him. Aphra allegedly dosed Moll with laxatives on a night she was due to visit the king, leading to an unfortunate incident that ended their relationship. (Moll was already pregnant by now though, and would have a daughter the following year.) Shortly thereafter Nell managed to attract the attention of the king when she sat in an adjoining box at a performance (that she wasn’t acting in, of course) and spent the entire play flirting with him. She went out to dinner with him after the play, accompanied by his brother James and her escort Mr Villiers (a cousin of the Duke of Buckingham). Another story (there are many stories about Nell) has it that when the time came to pay the bill the two royal brothers realised that that they hadn’t taken any money out with them and Nell had to pay for the dinner – which she did with a joke that this was clearly the poorest company she’d ever been in.

The king set Nell up with a house in Pall Mall and an allowance, but she loved the stage too much to give up acting straight away even when she didn’t need to. Word soon leaked out that she was sleeping with the king, leading to many wanting to come to her plays to see this new royal mistress. This popularity made sure that she became even busier, and that many roles were written with her specifically in mind. Nell continued to act even as her affair with the king (which many had assumed would be a brief fling) went on and became more serious. In 1669 she had to finish her season early when she found out she was pregnant, and in 1670 she had a son who she named Charles after her father. This wasn’t the end of her stage career though – she made a few more appearances in 1670 and 1671, possibly at the request of her friend John Dryden. In 1671 she retired from the stage for good and devoted herself to life at court, something which had become a necessity now that a genuine rival for Charles’ affections had appeared.

Louise de Kérouaille came from an ancient line of Breton nobles, rich in esteem if not in cash. She entered Charles’ life in a much more conventional way than Nell had. She was a lady in waiting to Charles’ sister Henrietta, wife of the Duke of Orleans. Louise was accompanying Henrietta on a visit to England in 1670 when the Duchess suddenly fell ill and had to rush back to France. Henrietta died a month later, [1] leaving Louise without a position. Luckily for her she’d made enough of an impression on Charles that he had his wife (the long-suffering Catherine of Braganza) take her on as a lady in waiting. Once in Charles’ court she was vigorously supported by the French ambassador (who hoped that she would influence Charles in favour of France, and possibly may have also planned to use her as a spy). Louise was smart enough to make Charles work for her affections, though not too much. She didn’t want to be a fling – she planned to make herself (like Barbara Palmer before her) the Queen in all but name.

Naturally, Nell didn’t take too kindly to this haughty French aristocrat who sought to displace her. Louise maintained a frosty and distant attitude to Nell, perhaps thinking that no commoner could truly last in the King’s affection. Nell though was somewhat less discreet. She gave Louise nicknames – such as “Cartwheel”, corrupting her surname, and “Squintabella”. Louise tended to respond to this teasing with tears, which merely led Nell to give her a new nickname – “Weeping Willow”. [2] One of Nell’s most famous court japes was at Louise’s expense, after the haughty Frenchwoman (who had persuaded the king to make her the Duchess of Portsmouth) went into mourning for the French prince Louis de Rohan in 1674. The Chevalier de Rohan had been executed by the French King for his role in planning a coup, but he was a member of one of the most noble French families and it was in sympathy with this that Louise wore black. The next day, Nell turned up in court wearing black and a noble asked her who she was in mourning for. “The Cham of Tartary”, she replied. “What relation was he to you?” she was asked. “About the same as that of the Chevalier de Rohan to Madame Cartwheel”, was the answer.

That story may (like many) be apocryphal, but it speaks to the general image that Nell had in the culture of the day. Stories about Nell abound, most (like that) revolving around her wit and in many cases her self-deprecation. For example, it’s said that she came across her carriage-driver arguing with another servant, and asked what the cause was.

“He said that my lady was a whore,” the driver told her.

“I am a whore. Find something else to argue about,” she replied.

In a similar vein was the story of Nell’s carriage being attacked as it went through the streets by a mob who mistook it for Louise’s carriage. As a French noble (and not a Protestant) she was ill-regarded by the public. Once Nell heard the attackers screaming about “the Catholic whore” she realised their mistake and opened her carriage window. Sticking her head out, she cried:

Good people, you are mistaken; I am the Protestant whore.

It’s claimed that Nell was so popular that the crowd were mortified to realise what they had done and gave her a profound apology before dispersing. Her popularity was in part fueled by her reputation for generosity – not only did she give her friends presents, she wasn’t shy about using her influence to help them. In 1679 her old fan Samuel Pepys had been imprisoned on suspicion of selling secrets to the French, for example, and Nell was instrumental in securing his release. In addition she’s often credited with persuading the King to found the Royal Chelsea Hospital for injured war veterans. She was also an enthusiastic patron of the theatre, and made sure to bring all her wealthy new friends along to the premieres of plays by her old friends like Thomas Dryden and Aphra Behn.

Unlike Louise, Nell never sought for a title for herself. However her first son Charles was granted a title by the King in 1676. There are contradictory stories of how this happened. One was that Nell, jealous of Louise’s son having a title, threatened to drop the boy out of a window unless he was ennobled. Another, more popular, story has it that when the king came to see the boy Nell called out to him “Come and see your father, you little bastard”. When the king protested Nell said that she could call him by no other title, so the king gave him an Earldom and the surname “Beauclerk”. The young man was later granted the title of Duke of St Albans, a title that his descendants hold to this day. Nell’s younger son James was also granted a title, but sadly he died in 1681 while studying at a school in Paris (possibly of an infected leg).

King Charles II died in 1685, a few days after suffering a fit probably caused by kidney failure. On his deathbed he had his brother James promise to “not let poor Nelly starve”. Though James and Nell didn’t really get on (she had nicknamed him “Dour Jimmy”), he honored his brother’s request and gave her a state pension in addition to paying off her debts. He tried to use this generosity to persuade her and her son to convert to Catholicism, which would have been a PR coup for him, but Nell was a proud Protestant and refused. Instead she retired from public life to her house in Pall Mall.

In March of 1687 Nell suffered a stroke – possibly as a result of syphilis, though there’s no direct evidence of this. She was left paralysed down one side, and remained ill until her death in November. Her funeral was conducted by Thomas Tenison, who would later become Archbishop of Canterbury. He had been a good friend of hers and had helped her make anonymous charitable donations. It was a sign of his esteem that he had her buried in the vaults of St Martin in the Fields, the church where he was vicar.

Nell’s legend and popularity only grew after her death, and to many she became a symbol of the London working classes. Her cheeky sense of humour and her refusal to take a title endeared her to the commoners and helped to ensure that her legend lived on. The saucy orange girl with the sharp tongue who caught the king’s eye became more real than the woman herself (indeed, her acting career was all but forgotten by many), while her unabashed embrace of her sexuality helped to make her almost a patron saint of the English adult industry in Victorian times. With the loosening of straitlaced standards Nell re-entered the mainstream in the 20th century, and went on to become a popular character on stage and screen. Who doesn’t love a real life rags to riches tale, after all?

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] It’s been alleged that she was poisoned, but given the state of medicine at the time whether this is the cae is anyone’s guess.

[2] The king’s nickname for Louise was “Fubbs”, and he named one of his royal yachts after her. HMY Fubbs was in service for 99 years under eight monarchs. She was the boat that carried King George III’s fiancee to England, though she was temporarily renamed Royal Charlotte for the occasion.

England have so many fascinating real stories like this.