Richard Dadd, Artist and Mentally Disturbed Killer

The cliched idea of the “thin line between genius and insanity” is one that has been discussed by both psychiatrists, cultural commentators and pop psychologists for decades. In one sense it’s an iteration of the “tortured artist” stereotype that’s used by those who hear about the miserable lives of the great creators and decide that it was necessary in order for them to have produced great art. In fact, it’s more often a side effect of the fact that artistic talent does not discriminate based on class, and the misery of these artists is merely a window into the misery suffered by the working class and ignored by history. Similarly the idea of mental illness linking to creativity is in general merely down to our larger focus on the mental processes of artists, such that when they are mentally ill it is impossible for historians to ignore it they way they do with politicians, aristocrats and military leaders. Worse, by doing so we all too often trivialise the very real tragedies that these illnesses have caused. And few are more tragic than the story of Richard Dadd.

Richard Dadd was born in Chatham in Kent on the first of August, 1817. His father Robert was a chemist by trade and a geologist and fossil-hunter by passion. Richard was seven years old when his mother Mary Ann died. At the time he was a student in the King’s School in Rochester, where he was already attracting attention for his skill in drawing. Robert remarried, but his second wife also died in 1830. The following year Richard graduated from the King’s School at the age of fourteen. By now his father Robert had turned his passion into a second career, founding the Chatham and Rochester Philosophical Institute as a local museum in 1828. Robert was the curator of the museum, though it wasn’t particularly successful. In 1834 Robert folded up the museum and moved to London, and his family (including Richard) came with him.

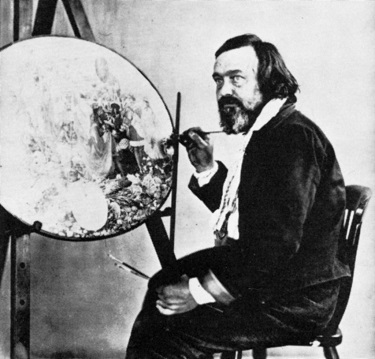

The family’s new location in London seems to have been chosen with Richard in mind, as it was right in the heart of London’s artistic institutions. Robert set himself up in business selling artistic supplies and applying gilding to frames. In 1837 Richard became a student in the Royal Academy of Arts, where he became the centre of a group of artists who were later labeled “the Clique”. These fellow students would hold social evenings where they would challenge each other to paint scenes from the works of their favourite writers, such as Shakespeare or Byron. Of this group Richard was the undisputed leader, and he was recognised as one of the rising stars of the Victorian artistic world.

As Richard transitioned from art student into professional artist, he carefully positioned himself in the market. The effect he was aiming for was to be seen as a dangerous “Lord Byron” style figure, while also remaining respectable enough to be hired. He wanted to be interesting, not infamous. There were no great scandals surrounding him, and instead he cultivated this “wild man” approach through his work. Hearkening back to the Clique’s games, his first shown piece was an illustration of a scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream called Titania Sleeping. This began a theme in his work of fairies and fairyland, though there was always a wild edge to his scenes. The revellers in the background of these pictures have a touch of the Maenad to them, and it seems believable that they could turn any moment and start tearing each other to shreds. Sadly none of his pieces sold for very much, but it was a start in getting his name out there.

In the summer of 1842 Richard Dadd was asked by Sir Thomas Phillips to accompany him on a trip through Europe and to tour the Middle East. Phillips was a lawyer who had previously been the Mayor of Newport (and was knighted for his service in stopping a Chartist uprising in the town). In return for his free holiday, Richard was expected to make drawings for Phillips of all the places they visited (possibly to illustrate a book about the trip). It was an old-fashioned type of arrangement, but one which appealed to Richard as a chance to see the world and gain a new source of inspiration for his art.

Sir Thomas turned out to be not quite an ideal traveling companion for Richard on the trip, though. He seemed to be more interested in ticking places to visit off his list rather than spending any time in them, which gave Richard very little time to draw them. While he enjoyed the trip, it wasn’t as professionally useful as he might have hoped. He did manage to fill a few sketchbooks at least, which provided some material for him in the years to come. It was the Middle East which had the greatest effect on him, as it was the most alien to his experience. The pair traveled through Turkey to Damascus, followed by a stay in Jerusalem. From there they went to Jericho where they caught a steamer to Alexandria in Egypt.

Richard was utterly delighted with Cairo, and he drank the city in like a thirsty man fresh out of the desert. He and Sir Thomas went on to see the Sphinx and the Great Pyramid at Giza, which were at the time the subject of frenzied archaeological research. This was the dawning of the great Victorian fascination with Ancient Egypt and its iconography. After that Sir Richard secured a boat with the plan being to sail up the Nile to Karnak. Though Karnak and Thebes were deeply impressive, the rest of the boat trip there and back dragged for Richard. By the time they returned to Cairo he was in “melancholic spirit”, and spending three weeks in quarantine in Malta after they left the country didn’t improve it at all. In fact he was in somewhat of a disturbed state when they moved on to the final leg of their trip: Italy.

The subject of Richard’s disturbance was one appropriate to their setting: religion. During the long Nile trip he and Sir Richard had discussed the Egyptian gods extensively, and now the Christian iconography surrounding him in Rome threw a contrast that caused his brain to go into meltdown. Because the truth is that Richard Dadd was on the long downslide into a full-on psychotic break; something that nobody in 1842 was capable of realising. In between insisting that the pagan gods were far superior to the Christian one he complained to Richard of being watched. What he didn’t share was that he thought the person watching him was the Devil. In fact, he caught sight of the devil once, in the form of “an old English lady in a lavender-silk dress.” When Pope Gregory XVI made a public appearance, Richard was far enough gone that he decided to attack him. However he was still in enough control to take note of the guards that the pope (who was afraid of being attacked in retaliation for his crackdown on Freemasonry) had surrounded himself with. So he and Sir Thomas left Rome without incident.

In Florence, Sir Thomas and Richard toured the great art galleries filled with Renaissance paintings that inflamed Richard’s mind even further. For example, he looked at The Conspiracy of Catiline [1] by Salvator Rosa, and he saw demonic horns and occult hand gestures indicating a deeper meaning. By the time he and Sir Thomas had arrived at their final stop in Paris, Richard could bear no more. Leaving Sir Thomas behind he fled home to London. There he retreated into relative seclusion, and his friends all thought that he was suffering from sunstroke. Some began to worry about his sanity, and watched carefully for any signs of mental instability. The paranoid Richard Dadd thus actually was being watched, just as he feared.

This didn’t impede his artistic output though, as sketches he had done on his journey matured into glorious Orientalist paintings. He even made contact with Sir Thomas Phillips and finally held up his end of the bargain to give him the illustrations of their trip. (The fact that he had done some excellent portraits of Sir Thomas himself probably helped.) Around this time Richard’s father Robert reached out to a friend of his, Dr Alexander Sutherland. Sutherland was a psychiatrist (though the word didn’t actually exist yet, so he was known by the unflattering title of “mad doctor”). On hearing the account of Richard’s behaviour he urgently recommended that Richard be hospitalised immediately. Whether Robert told Richard about this or not is unclear, but what is clear is Richard asked for his father to go away on a trip with him, so that he might “unburden his mind”. In August of 1843 the two men met in London and took a steamer together up the Thames, to Robert’s old hometown of Cobham.

It was evening when they arrived in Cobham, one of Kent’s most picturesque villages. It had played a role in Charles Dickens’ Pickwick Papers; a friend of Mr Pickwick had gone there to mend a broken heart and the titular hero had gone to fetch him home. He had found him in Cobham Park, and had commented that the beauty there was enough to mend any heartache. Richard was familiar with the park, as it held Cobham Hall where he had gone to sketch the collection of paintings in his youth. He persuaded his father to go for a nighttime walk there with him. Then as the pair walked through the moonlight, talking of things that we will never know, Richard Dadd murdered his father Robert.

Richard self-mythologised the murder later as the result of a sudden compulsion to offer the gods a sacrifice. He claimed that he struck his father down with a single blow, before offering a prayer to the god Osiris. The evidence tells a different and much messier story. First Robert was struck on the head from behind, then a razor was used to try to cut his throat, then he had been stabbed with a folding knife. Rather than offering a prayer, Richard had dragged the body towards a ravine by the path but had apparently been unable to brring himself to throw it over. And rather than a sudden impulse, there was evidence of some premeditation. Because Richard had secured a passport before he had met his father in London. And now Richard was on the run.

Robert’s body was found early the next morning (on the 29th of August), by which time Richard was already on a boat from Dover to Calais. He later claimed that his plan was to assassinate the Emperor of Austria. He took a coach towards Lyon, but as night fell he sat staring up at the stars. He thought he saw omens in them, and decided that the gods were demanding a new sacrifice. So he took the razor he had tried to cut his father’s throat with and attacked another passenger on the coach. The man was badly wounded, but Richard was soon disarmed and arrested. The French police soon identified him, and based on interviews he was sent to the asylum at Clermont, fifty miles north of Paris.

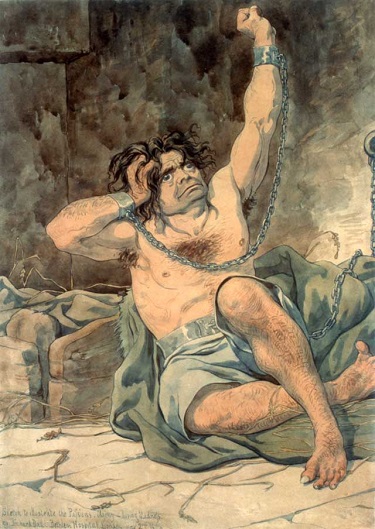

This was a few years after France and Britain had begun extraditing prisoners to each other, but the process was still in its infancy and it took eleven months for him to be returned to London. The French authorities had decided not to press charges for the assault due to his mental state, but had imprisoned him as a menace to public safety. Indeed, Richard told the French psychiatrists that it was now his sacred duty to kill all demons – and anyone might be a demon. Hydrotherapy (spraying him with cold water) gave little improvement, and that was as far as their therapy went. In July of 1844 an inspector from Scotland Yard came and collected Richard Dadd and took him back to England to face judgment for what he had done.

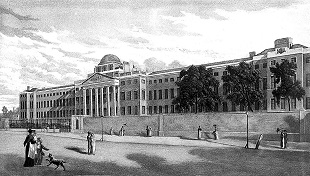

Public judgment of Richard was initially harsh. Many of his friends felt almost personally betrayed by his actions, and some even spoke of him as if he were already dead. The papers were convinced he soon would be; the fact that most so-called “lunatics” were usually suffering from neurosyphilis (podcast link) meant that there was a popular perception that mental illness would cause death. Richard’s siblings were torn, but they could not fully blame Richard for their father’s death after they had seen his state. They were happy that the authorities took the same view. At initial hearing Richard alternated between confessing, denying the murder, and verbally attacking the court. The judges decided that there was no need for a trial, as an insanity defense would probably succeed. [2] Instead they had Richard imprisoned indefinitely by court order as a “criminal lunatic” in the Bethlem Royal Hospital in Lambeth; better known then and now by its infamous nickname of Bedlam.

Bedlam was founded in 1247 as a priory for the Order of Our Lady of Bethlehem, a militant order of crusaders. In the 1370s it was seized by the Crown as the Order had aligned themselves with the Avignon popes (and thus England’s enemies, the French). By that point it had already begun to take in and house the mentally disturbed, and it claims to be Europe’s oldest psychiatric hospital. This claim is muddied by the fact that the hospital was demolished in 1803 and rebuilt on a new site. It had been an early target for the reformation of the treatment of the insane, and so though it was not a pleasant place for Richard to be it was far from the hell-hole depicted in fiction. In fact, it was not where the working class would have been sent at all. Its notoriety came from it being the “respectable” middle-class choice of asylum. At least, that was true for the non-criminal inmates. The criminals (like Richard) were a much more mixed bag, and he was held with the caution that his crimes merited.

That caution was justified, as for the first few years of his imprisonment he was definitely still a dangerous individual. He would lash out at others, and then offer his sincere apologies. It was not him guiding his hands, he insisted. It was the spirit that moved his hands, the son of Osiris who dwelled within his body. He was probably suffering from schizophrenia, though it’s impossible for us to say. Whatever it was, his disease was far beyond the ability of the primitive psychiatry of the day to treat. And whatever it was seems to have been hereditary in nature; his younger brother George was admitted to Bedlam around the same time he was. (Whether they ever met is unrecorded.) And his sister Maria would eventually also go into an asylum in Scotland fifteen years later.

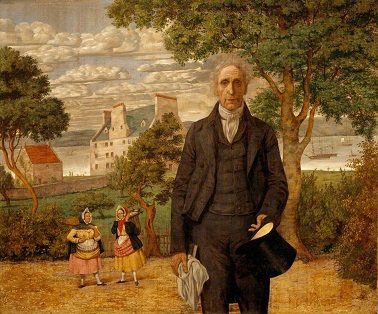

Richard began to paint again about a year after he arrived in Bedlam. His art had changed – matured, in some strange way. He drew from memory, and his fateful trip to the Middle East was generally his theme. Several of these paintings were acquired by Alexander Morison, a doctor at the hospital who became friends with Richard. Morison was among those who lost their jobs in a purge of senior management at Bedlam after an investigation found that standards of care in the asylum were far below regulation. He retired to Scotland, though not until after Richard had painted a portrait of him as a parting present.

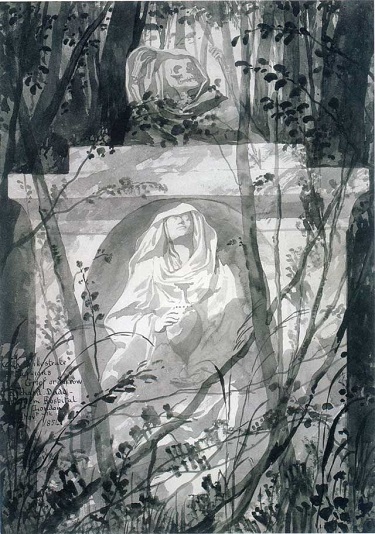

Several of Richard’s paintings during his time in Bedlam revolved around religious themes, mostly Christian (painting saints or biblical scenes) but some pagan. In one notable example Richard painted the discovery of Aesclepius, god of medicine, as a babe by shepherds on a hill. In a clear nod to the Christian parallels, Aesclepius was drawn with a halo. He was extremely prolific, and in 1853 he produced a thirty-part set of watercolours called Passions. Perhaps inspired by the psychology of his keepers, these paintings each covered a single “harmful passion” such as grief, treachery or jealousy. And then in 1854 he returned to a subject that had been a mainstay of his early career – fairies.

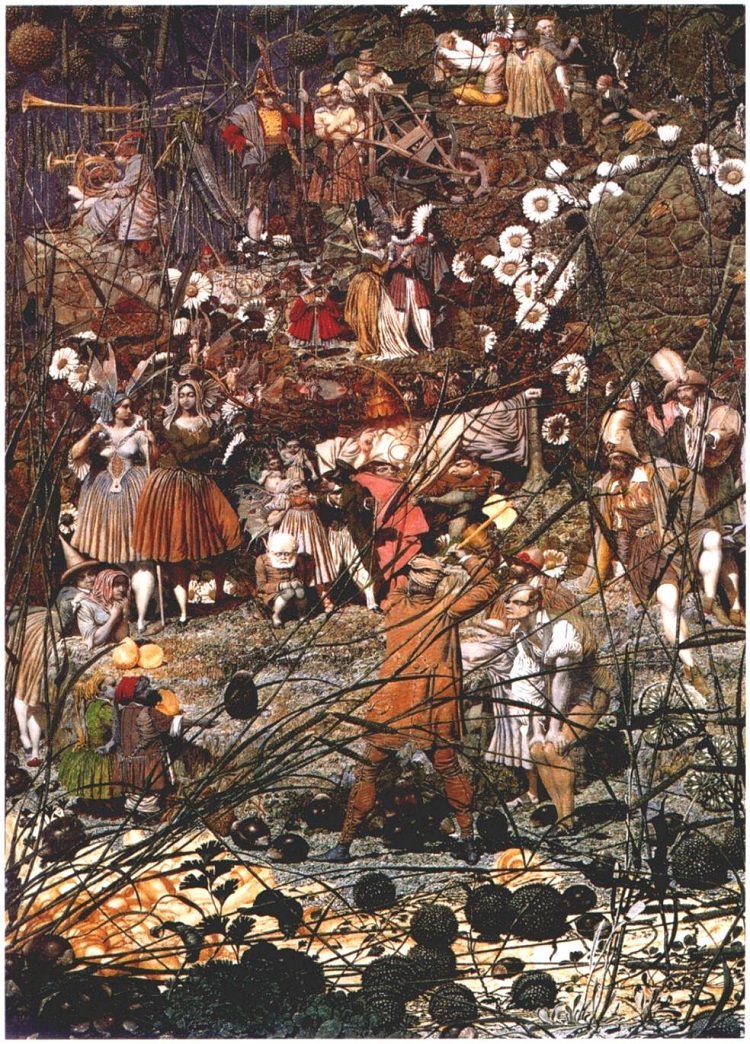

Fairies were popular in painting at the time, as they were through most of the Victorian period. However Richard was not painting for the mass-market. He was painting for himself. The fairy painting he created in 1854, Contradiction: Oberon and Titania, marks the point where he truly embraced that freedom from the constraints of commercialism. If his early fairy paintings had been dreamlike, then Contradiction”was the nightmare born of a fever. Detail crowds the frame to the point of bursting, and every glance reveals a new secret. Oberon and Titania both are more reminiscent of the Middle Eastern people Richard had painted in the past, rather than their traditional ethereal depiction. The painting captures perfectly both the troubled mind of its creator and the uneasy disquiet of the best fairy horror tales. It took Richard four years to paint, and was unlike anything else.

It was shortly after he completed Contradiction that Richard began sketching out what would eventually be considered his masterwork, though it would take six years for him to paint. Once again it involved fairies, and once again they were linked to Shakespeare. This time the play was Romeo and Juliet, and the fairy in question was Queen Mab. Mab was, according to Shakespeare, the “fairy midwife” who birthed dreams in the heads of dreamers. She does not appear in the play, but is rather the subject of a monologue that Mercutio uses to entertain Romeo:

“O, then I see Queen Mab hath been with you.

She is the fairies’ midwife, and she comes

In shape no bigger than an agate stone

…

Her chariot is an empty hazelnut,

Made by the joiner squirrel or old grub,

Time out o’ mind the fairies’ coachmakers.”

The painting is not of Queen Mab herself, but rather shows a fairy axeman poised to chop a hazelnut and make her a new carriage. The entire miniature court has turned out to watch him perform this feat, providing a level of detail possibly even greater than that of Contradiction. Unlike the earlier painting though, The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke is infused with a lushness and realism that draws the viewer in. Reeds in the foreground place the viewer within the architecture of the world. We are one of these fairy creatures, drawn to see the feller perform his feat.

Richard wrote a poem about the painting, called Elimination of a Picture & its Subject. It’s a fascinating insight into his thinking at the time. It begins by reminiscing about Contradiction, meanders through the fairy world to come to the moment of this painting and to the feller with his axe upheld, before wandering around the other characters of the painting in a loose stream of consciousness.

He with one blow, another turn will serve

If from the aim’s intent it doth not swerve

Left to its time & how to do

To split, for Mab perchance a chariot new.

’Tis all the skill there is for such a deed

Happen, happening in faerie for fairy’s need.

See – ’tis fay woodman holds aloft the axe

Whose double edge virtue now they tax

To do it single & make single double

Teatly and neatly – equal without trouble

’Tis not yet done – yet there he stands.

By the time Richard wrote that poem, he had left Bedlam behind. Not through release – rather, he and all the other “criminal lunatics” had been moved to a new purpose-built prison/hospital in Berkshire. This was what would become home to some of Britain’s most notorious killers – Broadmoor Hospital. Richard was housed in the block reserved for permanent patients who were not considered specifically dangerous, alongside others such as William Chester Minor. William was a former American army surgeon who had shot a man he believed to be stalking him while in the grip of a paranoiac delusion. He was an etymologist who wound up, through letters from Broadmoor, contributing a large amount of content to the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary.

Like William Minor, Richard Dadd was given the leeway to continue to pursue his hobbies in Broadmoor. He painted landscapes and at least one painting of a Dartmoor official, but most of his work barely progressed beyond outlines. One outlet for his art was stage-painting; he created backdrop curtains and scenery for the Broadmoor stage productions. His paintings were now more conventional and his final oil painting The Wandering Musicians has an almost classical restraint to it. The ancient Greek architecture in the background shows where his mind was at the time, as his previous painting showed the ancient Greek myth of Atalanta racing Hippomenes.

An 1877 article about Richard published in the World magazine prompted some interest in this incarcerated artist, and his works began to receive a bit of exposure in the artistic world. His health was in gradual decline though, due to a lack of exercise and his long confinement. In 1885 he fell ill with tuberculosis, and early in 1886 he died. He was buried on the asylum grounds. His art was largely forgotten until the 1930s, when The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke was given as a wedding gift to the poet Siegfried Sassoon. He loaned the painting to various museums, and its uniqueness was soon recognised.

By the 1960s the painting had been bequeathed to the Tate Gallery by Sassoon and it became a pop culture icon. In 1974 the band Queen even released a song named after and based upon the painting. Plays and poems soon came to be written starring Richard Dadd, all mythologising this figure of the “tortured artist”. Just as he, in the throes of his illness, had reinterpreted his world in symbolic figures and archetypes; now he himself became a symbol. The messy complexity of the man was, as always, left behind by the legend.

Pictures via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] Catiline has of course been covered in this column before.

[2] Though since the legally valid insanity defence was in its infancy, it’s hard to be sure. The decision of the judges may have been as much about not putting too much stress on that new system.