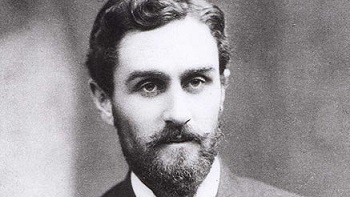

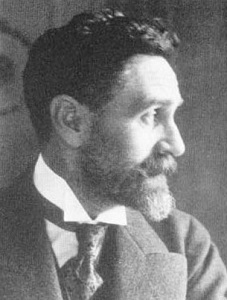

Roger Casement, British Knight and Irish Martyr

Roger Casement was born in Dublin in 1864. His father, Captain Roger Casement, was a Belfast-born soldier who had served in India and fought in the bloody war for Afghanistan in 1842. Young Roger was raised on his father’s tales of travel, and subjected to his father’s harsh military discipline. In contrast his mother Anne was affectionate to both him and his brothers, though only out of sight of his father. There’s a story that Anne, who was the child of a religiously mixed marriage, held secret Catholic beliefs despite being outwardly Anglican. When Roger was three years old the family moved from Dublin to Wales, and the story is that Anne had him secretly baptised as a Catholic when he was four. When he was only nine years old, Anne died. The cold discipline of Captain Roger crumbled at her death, and he suffered a complete nervous collapse. After he recovered the captain became obsessed with contacting Anne and was a fervent devotee of the Church of Spiritualism. As a result of both that collapse and his father’s need to go abroad once he recovered, Roger and his brothers were sent to live with Captain Roger’s uncle John in Ballymena.

Roger was an intelligent and athletic child, the kind that was confidently told (based on his background) that he could conquer the world for the Empire. His father died when he was thirteen, while Roger was attending the Diocesan School in Ballymena. In 1880 he left school and went to live in Liverpool with his aunt Grace, working for a Manchester-based shipping company named Elder Dempster. He disliked office work, but this did give him an opportunity to follow one of his dreams. Roger had been a huge fan of the stories of great explorers like Henry Morgan Stanley, and so in 1884 he took a position as purser on a ship going to the Congo. This led to an opportunity to work with his hero, Stanley himself.

At the time Leopold of Belgium had just managed to gain control of the “Congo Free State” as effectively a private possession. In order to properly exploit it, Leopold needed men like Roger Casement to survey it for him. This was not the heroic adventure Roger had dreamed of – this was a brutal subjugation of a country and its peoples. Roger was not exposed to the worst of it – not yet. He commanded an effort to build 220 miles of railway through the jungle, bypassing the impassable portions of the Congo River and ensuring that all the country’s wealth would flow to the coast. Roger worked for Leopold and Stanley for the best part of five years, and at the end of that time his youthful idealism was dead and buried.

Roger left alongside a friend of his, Herbert Ward. The two had joined Leopold’s service at the same time, but Ward had left after only a couple of years. He was recruited by Stanley for his ill-fated expedition to rescue Emir Pasha, and was one of the few survivors of the Rear Column. It was probably to let him escape the publicity (and the trauma) of the descent into madness that befell the Rear Column of that disastrous expedition which sent him and Roger across the Atlantic to America. The pair became the best of friends, and Ward described Roger as:

…a tall, handsome man, of fine bearing; thin, mere muscle and bone, a sun-tanned face, blue eyes and black curly hair. A pure Irishman he is, with a captivating voice and singular charm of manner. A man of distinction and great refinement, high-minded and courteous, impulsive and poetical.

Following their American trip Ward went to London (he would later move to Paris and become a sculptor) while Roger returned to Africa. It was around this time (though it may have been before his trip to America) that he first met the writer Joseph Conrad. The two had much in common – both had come to Africa filled with ideals of high adventure, and both had been thoroughly disillusioned by it. Like Ward, Conrad was deeply impressed by Roger. He later described seeing him:

…start off into an unspeakable wilderness swinging a crookhandled stick for all weapons, with two bulldogs, Paddy (white) and Biddy (brindle) at his heels and a Loanda boy carrying a bundle for all company. A few months afterwards it so happened that I saw him come out again, a little leaner a little browner, with his stick, dogs, and Loanda boy, and quietly serene as though he had been for a stroll in a park.

In 1892 Roger began working for the British government, and in 1895 he was made the consul to Portuguese East Africa. It was a turbulent time in Africa as the various colonial powers sought to consolidate their holdings, leading eventually to the outbreak of the Boer War in 1899. Roger’s conduct in support of this stood out enough to earn him a medal, and to put him on the radar. At the time there was a great deal of public misgiving in England based on the reports coming out from the Congo of King Leopold’s behaviour there, and given his previous connection with the regime Roger was a logical choice to send out there. But nothing could have prepared him for the horror he found.

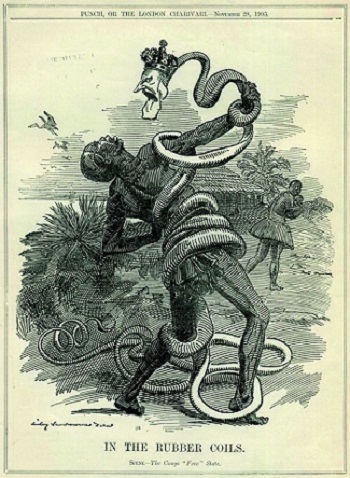

The main goal of Leopold’s regime in the Congo was to extract as much rubber as possible from the region, rubber being the most valuable export. Every village was expected to provide a punishingly high quota of rubber, and those who failed to meet these quotas were subjected to punishment raids from government troops. Beating, torturing and organised rape were all used as tools to punish villages, along with execution of hostages. The troops were incentivised to save ammunition by being ordered to chop the hands from every person they killed, so their kill to shot ratio could be tracked. Many would harvest the hands of living workers in order to improve their ratio and earn bonuses, and some villages would raid other villages to kill them and/or harvest their hands in order to give them to the soldiers and thus earn themselves a reprieve from a raid.

One witness Roger interviewed told of his little sister being killed and thrown into a burning building, and of being forced to carry baskets containing the severed hands of his murdered friends and relatives. Another spoke of seeing the hands delivered and counted by a white man, who counted two hundred hands. The pictures that accompany Roger’s report, of young children missing hands and of people with bones broken and badly healed, are heartbreaking. The lack of time to raise food led to mass starvation and more suffering. As the over-harvesting of rubber killed off the vines close to the villages, the villagers were forced to travel further to make up their quotas and they were preyed on by wild beasts. When they appealed to their oppressors for mercy, they were told: “Go! You are only wild beasts yourselves.”

Casement’s report made for disturbing reading, and he was put under some pressure to moderate his language. He resisted, and the eventual report in 1903 was forty pages of his meticulous and heartbreaking detailed reporting, along with twenty pages of individual statements. The British government sent copies of the report to the Belgian government and to all the other governments who had signed the 1885 agreement that had (among other things) given Leopold his control over the Congo. As a result the Belgian parliament set up a commission of inquiry that confirmed the details of the report, and many of the specific crimes covered in it were investigated and prosecuted. However the sentences handed out were laughably weak (one official responsible for 122 deaths was sentenced to only five years in prison), and Leopold retained his personal control over the Congo until 1908.

In 1906 Roger was sent to Brazil, where he was promoted up the chain until he became consul-general. In 1909 he was attached to a commission investigating abuses in the rubber industry once again, but this time it was into a British company operating in South America. A journalist named Walter Hardenburg had written an article for the magazine Truth about the Peruvian Amazon Company, and the extreme mistreatment of its workers harvesting rubber in the Putumayo region. [1] Most of its workers were natives, drawn from the area, but some were from the British colony of Barbados. This gave the Foreign Office the pretext it needed to send in Roger, though the real reason was that the directors of the PAC were British. The founder of the company, Julio Cesar Arana, had come to London to raise funds to set it up a few years earlier, and the whole world knew that it was British moneymen bankrolling the PAC. So to defend the honour of the Empire, Roger went into hell once again.

Though the details varied, what Roger found in Putumayo was little different from what he had found in the Congo. The workers were treated as slaves, flogged or murdered for the slightest infraction or sometimes just for the amusement of their overseers. There was rape on a wide and organized scale, mutilation, and people burned alive. Children were killed to punish their parents. The overseers would douse people in kerosene and set them on fire in order to laugh at them burning alive. Casement travelled through this, under an armed guard as he knew the PAC would be happy for him to suffer an “accident”. He took eye witness testimonies, and wrote of the horrors he saw with his own eyes. And what he wrote changed the world for the better.

Roger Casement’s report on the Putumayo had a huge effect in London. The Times praised Roger in florid terms, while a sermon at Westminster Abbey described what he had uncovered as “the most infamous oppression that has ever served the interest of cupidity or stained the record of despotism”. It was the end of the PAC, which was closed down by court order in 1913. It was the end of wild rubber farming in general, in fact – the PAC’s brutality had in part been driven by desperation to compete with farmed rubber, as Sri Lanka and Malaysia had proved to be fertile ground for the foreign trees. As a result, the end of the PAC meant an end to the oppression of the Putumayo natives. Roger is still remembered by them as their liberator to this day.

If Roger Casement’s career had ended there, he would be considered a solid candidate for one of the most revered Britons in history. His work laid the foundations for human rights activists of the following century, and earned him a knighthood. But Sir Roger Casement was about to embark on a course that would see him reduced, in the eyes of many of his then friends, to the lowest of the low. Though in fact this wasn’t really a new path – just one that they had chosen to ignore. In 1904 while on holiday back home in Ireland Roger had joined the Gaelic League, officially an apolitical movement dedicated to preserving the Irish language but in practice a hotbed of Irish nationalism. With Roger’s faith in the Empire shaken by his experiences in the Congo and the lack of any long-term impact, it isn’t surprising that he would get swept up in it, and he joined Sinn Fein in 1905.

Roger’s position at the Foreign Office meant that he had to keep his new beliefs under cover, though. At most he could have been an open supporter of Home Rule for Ireland, which by 1913 was beginning to look inevitable. [2] But Roger was convinced that Home Rule was a pointless goal. Any previous attempts had been derailed by the House of Lords, and Roger didn’t think things would be any different now. As an Ulsterman by residence if not by birth, he was also well aware of both the strength of the Unionist feeling that was based in the province and the reality of how home rule would be received. He was sure that the only real change could be independence, and once he retired from the Foreign Office in 1913 he was free to do his best to make it happen.

In January of 1913 the Ulster Volunteers were formed in Belfast. They were an open opposition to the concept of Home Rule, with tacit backing from the Conservative party in Britain. They pledged to block self-government “by force of arms if necessary”, as they saw it as a stepping stone to independence and Catholic domination. [3] In opposition to this the nationalists formed the Irish Volunteers. Ostensibly it was Eoin MacNeill, a history professor at UCD, was the one who called for their formation though in actuality the Irish Republican Brotherhood [4] were the ones organising it. MacNeill was just a respected face, though he didn’t let them pull his strings. Roger Casement was also a natural choice for the public side of this new movement – internationally respected, he gave them an immediate credence. He was a member of the leadership committee from the beginning.

Well aware of the mood in Ireland, the Liberal government in London banned the importation of weapons into Ireland after these two rival factions formed. In April of 1914 the Ulster Volunteers successfully smuggled around 24,000 rifles into Ulster through the port of Larne. Though the potential effectiveness of this has been disputed (some accounts say that they would not have had enough ammunition for these guns) it was a huge publicity coup for them and was highly publicized (a Belfast Telegraph reporter was on the docks with them). As a result the Irish Volunteers felt they had to follow suit. In July of 1914 Roger was among those who organised a shipment of rifles to Howth, though the 1000 weapons they received were arguably less influential than the aftermath – a British army regiment sent to unsuccessfully intercept them was attacked by a mob on returning to Dublin and opened fire on them. Four people were killed, around ten times that many were wounded, and the numbers of the Irish Volunteers swelled as a result.

Roger was in America meeting with John Devoy in the summer of 1914. Devoy was the editor of the Gaelic-American and a prominent figure in American Fenianism. He had been unofficially exiled from the British Isles in 1871 and had since then been active in America raising funds and organising aid for Irish rebels. He was helping Roger to raise support for the Volunteers in August when war between Britain and Germany was declared. The war put an end to the prospect of immediate Home Rule, and it also divided the Irish Volunteers. Those who favoured Home Rule thought that Irishmen should go and fight to prove their loyalty (and incidentally pick up some military training on the side), while those who favoured independence thought that Irish blood should not be spilt in service of British interests. Some went further – they made their motto “England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity”. Roger was firmly in the latter camp – as soon as he heard about the war, he got Devoy to arrange a meeting with the German ambassador to America.

Count Johann von Bernstorff was not a man averse to dirty dealings. Over the course of the war he would direct German sabotage efforts in Canada to try to impact that country’s support of the European effort, and he would also stage covert attacks on American weapons companies that sold to the Allies. He and Roger hammered out an agreement where Germany would provide guns and officers to lead Irishmen in revolt against British rule. In October of 1914 Roger traveled to Germany, and December of 1914 he and Arthur Zimmerman, the German foreign minister, officially signed an agreement pledging German support for Irish revolution.

Roger spent over a year in Germany trying to organise his revolution. His initial plan was to recruit from among Irish prisoners of war, but few of the men who had volunteered to fight for Britain were willing to risk a death sentence for fighting against her. (A similar effort to support rebellion in India failed for the same reason.) Eventually he was told of the plan for a rising at Easter of 1916. He didn’t get the German officers he wanted, but he did get twenty thousand rifles and ten machine guns. Unfortunately for him, the ship carrying the guns was intercepted by the British Navy and captured en route.

Casement himself was put ashore on the coast of Kerry on the 21st April. It was later stated that his main aim was to try to convince the leaders to cancel the Rising, as he was convinced that Germany now didn’t intend to support it enough to see it succeed. Whatever his intentions, they were frustrated by a sudden attack of malaria that left him unable to travel and forced him to try to hide out in a nearby Celtic ringfort while the man who landed with him, Robert Monteith, went to try and get help. Before Monteith could return though, Roger was discovered and captured by the local police.

Reportedly while being interrogated in Scotland Yard Roger tried to get them to let him communicate with Dublin to call off the rising, but the authorities refused claiming that “a cankering sore like this should be cut out”. Three days later, the Irish Volunteers rose up in Dublin. Five days after that, they had been defeated. Though Roger Casement hadn’t taken part in the Easter Rising, his international fame ensured that his name was linked to coverage of it throughout America and England. It also probably sealed his fate. The British secret services were aware of his activities in Germany, and they made sure everyone was aware of it. However that wasn’t the only information they made sure everyone knew. They circulated excerpts, supposedly from Roger Casement’s private diaries, and started a controversy that continues to this day.

While Roger had been in South America he had kept a diary of his trip, in order to compile his official report. It was now claimed that this was only one of two sets of diaries that he kept. The public records were referred to as his “White Diaries”, while the others were the “Black Diaries”. And what did he record in them? Allegedly, detailed descriptions of all his homosexual encounters during the trip. The excerpts chosen to be given to the press were not obscene in language, but they were detailed enough to leave little doubt as to what Roger got up to. As a result the excerpts were not printed in the papers, but everyone in a position of influence knew about them.

Whether the Black Diaries were real or forgeries, the main purpose of releasing them was to ensure that any attempt to gain clemency for Roger would fail and to taint any status he might have as a martyr. After being captured he was transported to the Tower of London and held prisoner there. He was formally charged on the 13th May, the day after the last of the executions in Dublin of the leaders of the Rising. The trial took place on the 26th of June, and ended on the 29th of June. Roger argued that as an Irishman he should be tried by an Irish jury, but it was ruled that a British subject committing treason abroad could only be tried by the King’s Bench. His defense was based on an interpretation of the statute laid down by Edward III defining treason, and an argument that under it acts committed outside of British territory could not be considered treasonous. This was actually a possibly legally valid point at the time, and one which could have spared Roger a death sentence. But the statute was in French and unpunctuated, and the judge decided that it should be punctuated in such a matter that it also applied to crimes outside of the realm. This led to Roger’s bitter complaint that he was being “hanged on a comma”.

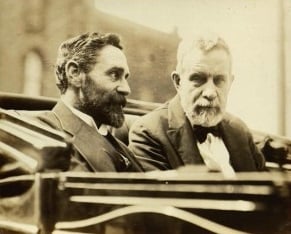

Roger was found guilty, of course – the evidence was overwhelming. He was stripped of his knighthood and sentenced to death. There was a campaign for clemency, which was as mentioned undercut by the release of the Black Diaries. There was a good chance that Roger could have gained clemency regardless, if his crimes had been confined to raising rebellion in Ireland. Eamon de Valera, for example, had escaped execution due to his American birth and influence. Roger was a well known and popular figure, and there was some pressure from America for mercy. But his having directly colluded with the Germans was a crime that few could forgive. Arthur Conan Doyle, a great admirer who had based the main character of The Lost World on Roger, started a petition for mercy but garnered few signatures. Joseph Conrad refused to sign, as did Herbert Ward. Ward’s son had been killed on the Western Front that year, and he was so upset by Roger’s treachery that he had the name of a younger son (who had been Roger’s godson and named after him) legally changed. The only signatures on the petition were the usual supporters of Irishmen – Yeats, Shaw and the like.

Roger’s appeals likewise failed, and the sentence was carried out at Pentonville Prison on the 3rd August. He had formally converted to Catholicism before the execution, though it’s rumoured that the priest he saw before the execution refused to hear his confession on account of his “degeneracy”. He was buried in a traitor’s grave on the Pentonville grounds. After the foundation of the Irish state a formal request was made for the repatriation of his remains, which was refused. Finally in 1965, with the 50th anniversary of his death approaching, Prime Minister Harold Wilson agreed to return the body. Roger’s will had stated his wish to be buried in Antrim, but Wilson’s one condition was that the bones could not be buried in Northern Ireland as he knew this would cause trouble. So Roger was laid to rest in Glasnevin Cemetery, alongside the other martyrs of the Rising.

I poked about a village church

And found his family tomb

And copied out what I could read

In that religious gloom;

Found many a famous man there;

But fame and virtue rot.

Draw round, beloved and bitter men,

Draw round and raise a shout;

The ghost of Roger Casement

Is beating on the door.

– from The Ghost of Roger Casement, by WB Yeats

In the decades since, Roger Casement’s life and legacy has remained a subject of discussion. The main debate has always been over the infamous Black Diaries – are they genuine, or were they forged by the British secret services to discredit Roger? The diaries have been definitively declared both real and fake several times over by every possible expert, and at this stage it has become simply an article of faith either way for all involved. As such, it’s effectively impossible for a layperson to know if they’re fake or not. Not that, in the long run, it really matters. What’s more interesting is how people have reacted to the idea of Roger Casement being gay. [6] At the time both sides of the debate considered the idea of homosexuality abhorrent, and so to say that he was gay was to blacken his reputation. The Irish State in 1965 far preferred to bury a sexless martyr to the cause, while the British government had no wish to dredge up their own dirty dealings (in either forgery or selective leaking). Even in relatively recent times one historian “defended” him by referring to the “virtual impossibility of his practising the gross degeneracies at all”, while other historians have slyly implied that he was a sexual predator. There have even been attempts to reclaim him as a gay icon for Ireland – proof that the history of this nation was more diverse than tradition would have it. Maybe one day we’ll be able to point to Roger Casement and define him, for now it seems likely that we’ll still be trying to figure him out for a long time to come.

Pictures via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] At the time controlled by Peru but under dispute between various South American countries, currently part of Columbia.

[2] It’s generally speculated by historians that if not for the outbreak of World War I then Ireland would have been probably have been granted Home Rule by the end of 1914. If so this would almost certainly have led to a civil war, as Unionists were wholeheartedly against the idea.

[3] Given a lot of the things that went on in Ireland in the 20th century and are only now getting attention, all their talk of “Catholic domination” does seem a lot more plausible.

[4] A secret society that had been formed fifty years earlier to coordinate and direct the republican movement.

[5] Kathleen Clarke (wife of Easter Rising leader Tom Clarke and later Mayor, TD and Senator) is on the record as saying that Roger was only ever supposed to be getting guns anyway. She’s also less than flattering about him in general, though her view seems slightly at odds with the general record.

[6] Which is less debated, but still fervently denied by many.