Ungern von Sternberg, the Bloody White Baron

It seems ironic that one of the most fearsome of the White Russian generals was very nearly an Austrian officer, for there is much in common between Ungern von Sternberg and a certain Austrian corporal who fought on the opposite side of World War I. This is no exaggerated comparison – both possessed a ferocious antisemitism and genocidal rage, and both spent other people’s lives like water in pursuit of a futile goal. In another world the two would have been natural allies. Perhaps we should be grateful that the White Baron did not wind up on the western side of the Russo-German border.

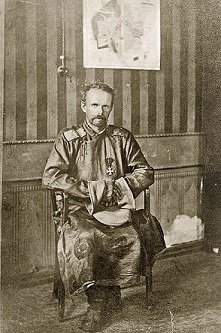

Roman Fedorovich Nikolai Maximilian von Ungern-Sternberg was born in Austria on December 29th, 1885. His father, Theodor Freiherr von Ungern-Sternberg, was a Baron and Roman was his eldest son. [1] Theodor and his wife Sophie moved to Reval (modern day Talinn) in Estonia in 1888, as this was their family’s original homeland. In 1891 they divorced, an unusual step in those days that was caused by Theodor’s rages and cruel treatment of his wife. Three years later Sophie remarried, and Ungern (as he later styled himself) lived with her and her new husband. Ungern received a standard noble’s education, and showed a marked keenness for a military career. In 1903, at the age of 17, he enrolled in the Marine Cadet Officer’s School in St Petersburg, at the time the capital of Russia. He gained a reputation as a troublemaker, and, in the words of one of his school-mates, “a man who bullied the bullies”. The Russo-Japanese War broke out in 1904 and Ungern immediately put in for a transfer to fight in it, but this was refused. Undeterred, in 1905 he dropped out of the school and headed to Siberia.

Roman Fedorovich Nikolai Maximilian von Ungern-Sternberg was born in Austria on December 29th, 1885. His father, Theodor Freiherr von Ungern-Sternberg, was a Baron and Roman was his eldest son. [1] Theodor and his wife Sophie moved to Reval (modern day Talinn) in Estonia in 1888, as this was their family’s original homeland. In 1891 they divorced, an unusual step in those days that was caused by Theodor’s rages and cruel treatment of his wife. Three years later Sophie remarried, and Ungern (as he later styled himself) lived with her and her new husband. Ungern received a standard noble’s education, and showed a marked keenness for a military career. In 1903, at the age of 17, he enrolled in the Marine Cadet Officer’s School in St Petersburg, at the time the capital of Russia. He gained a reputation as a troublemaker, and, in the words of one of his school-mates, “a man who bullied the bullies”. The Russo-Japanese War broke out in 1904 and Ungern immediately put in for a transfer to fight in it, but this was refused. Undeterred, in 1905 he dropped out of the school and headed to Siberia.

There are conflicting reports as to how Ungern’s trip to Siberia went. Some say that the fighting was over by the time he got there (the war did end in 1905). Others say that he joined a unit of Cossacks and saw some action, and he definitely saw enough of Siberia to wish to return there. Regardless, by 1906 he was back in St Petersburg. He enrolled in the Pavel Military School, which placed him in the regular army – the Marines clearly having given up on him. After he graduated he returned to Siberia where he was an officer in the Amur Cossack Host. Here he was exposed to the local tribal peoples, the Mongols in particular. His admiration of the Mongols and their military heritage would shape the rest of his life as well as the destiny of the Mongol people. He was also fascinated with Eastern religions, and tried to form “the Order of Military Buddhists”. [2] The fact that his rules for members included celibacy ensured he met with limited success. In 1913 he completed his tour, and retired from the military into the reserves. The next year, of course, he was back in the field.

For the majority of the First World War, Ungern was pitted against his ethnic brethren on the “Eastern Front”. Fighting fellow Germans doesn’t seem to have bothered him, and he gained a reputation for recklessness, mixed with enough competence to ensure it won him medals and not an early grave. His lack of regard for orders did see him discharged from one of his commands. In February 1917 the Tsar was overthrown and replaced by a democratic government, though to ensure much-needed support from the West the new government was forced to continue fighting in the war. As part of the shakeup Unger was transferred from the German front south to the Caucasus, where the fight was against the Turks. It was here that he met his future commander and friend, Grigory Semyenov. Grigory was a Cossack with Mongol blood, exactly the type that Ungern admired. Both were outcasts among the other officers for their ethnicity, and so they naturally came together. And it was together that they declared their opposition when, in October 1917, Lenin and his Bolsheviks overthrew the new government in the name of Communism.

For the majority of the First World War, Ungern was pitted against his ethnic brethren on the “Eastern Front”. Fighting fellow Germans doesn’t seem to have bothered him, and he gained a reputation for recklessness, mixed with enough competence to ensure it won him medals and not an early grave. His lack of regard for orders did see him discharged from one of his commands. In February 1917 the Tsar was overthrown and replaced by a democratic government, though to ensure much-needed support from the West the new government was forced to continue fighting in the war. As part of the shakeup Unger was transferred from the German front south to the Caucasus, where the fight was against the Turks. It was here that he met his future commander and friend, Grigory Semyenov. Grigory was a Cossack with Mongol blood, exactly the type that Ungern admired. Both were outcasts among the other officers for their ethnicity, and so they naturally came together. And it was together that they declared their opposition when, in October 1917, Lenin and his Bolsheviks overthrew the new government in the name of Communism.

The two men took their troops east to Siberia, feeling that they would be most effective on familiar ground. The area was the stronghold of the White Russian forces, but Semyenov refused to acknowledge the authority of their leaded Admiral Kolchack. Kolchak was noted for his racism, and so would probably have removed Semyenov from his command anyway. Instead Semyenov, and Ungern beneath him, allied themselves with the neighbouring Japanese empire for support. This allowed them a strong enough position that Kolchak was forced to acknowledge them as military commanders in their districts. In addition, Semyonov declared himself Ataman, or supreme military leader, of the Cossacks, and was reported to be considering establishing a Cossack nation with Japanese backing. Ungern was given the task of harrying the Bolshevik forces, and to that end he formed a volunteer division. This division accepted any who came, Russian, Mongols of various tribes, Cossacks, and even Chinese and Japanese volunteers. Their official title was the Asiatic Mounted Cavalry, but they became better known under their nickname, “The Savage Division”.

Relations between Ungern and Semyonov deteriorated over the next few years. While Semyonov continued to work towards independence, Ungern became convinced that only a restored Romanov as absolute ruler could solve Russia’s woes. He saw any form of democracy as decadent and dangerous, and believed that people required an absolute monarch to lead them out of anarchy. He released a manifesto in 1918 declaring his intention to restore Grand Duke Mikhail, son of the abdicated Tsar, to the throne. The only problem being that Mikhail had been secretly murdered by the Bolsheviks a few months earlier. Once word of this got out, Ungern seems to have given up on Russia as lost, at least for the moment. Instead he decided to work towards an independent Mongolia, visualising the revitalised Mongols cascading outwards in a repetition of history. (Ungern admired Genghis Khan, who he saw as a cleansing force of history.) In preparation he allied himself with the Manchurian Chinese, marrying a Manchurian princess in July 1919 to seal the alliance. [3] In August 1920, as the White Russian forces in Siberia were disintegrating under Bolshevik attacks, Ungern took his Savage Division and headed to Mongolia to bring his dream to life.

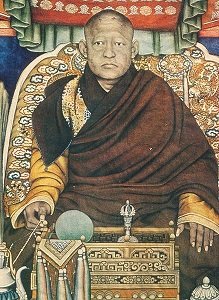

At the time, Mongolia was ruled by warlords in service to the Republic of China. To replace them Ungern planned to install a Buddhist monarchy, modelled after that of Tibet. His proposed monarch was the 8th Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, believed to be a line of reincarnations descended from the Tibetan Lama and scholar Taranatha. The first such reincarnation (in the 17th century) was Zanzabar, son of Gomborj who was khan of Mongolia at the time. As such the reincarnations of Tanatha became the spiritual heads of Buddhism in Mongolia, taking on the title of Bogd Gegen. The current Bogd had been born in 1869, and moved to the capital of Urga upon recognition in 1874. [4] In 1911 he had declared himself the Bogd Khan, ruler of an independent Mongolia, and had been recognized as such by both Russia and Tibet. In 1915 he had been forced to subject himself to Chinese rule, though Mongolia retained its autonomy – at least until 1919, when China sent in its army to assert dominance. The invasion of the Chinese had severely curtailed his power, and he had sent secret missives to Ungern inviting him to invade. In 1920 he got his wish.

In October 1920 Ungern led the Savage Division across the border into Mongolia. His initial demands to the Chinese occupiers that they stand down and disarm were rejected, and open hostility immediately broke out. His first attack on Urga was beaten back, and he retreated to the surrounding hills to lick his wounds. The locals, however, flocked to his banner. Ungern had adopted local dress, and followed many of their customs, and the vicious discipline he imposed on his troops helped to prevent them from driving the locals off with the savagery they had become known for in Siberia. One story has it that he forced a group of men found being drunk on duty to march out naked into the middle of an icy winter river, where they were attacked by wolves and had to fight them off with their bare hands. Half the men were killed. Not for nothing did the locals whisper that the Baron was an incarnation of Begtse-Mahakala, the Lord of War. With his forces bolstered by the local recruits, the Baron determined to overawe the opposing forces. His men spread out in the hills and lit fires, creating the impression that his forces had the city surrounded, while his local recruits infiltrated the capital and spread the rumour that the White Baron could be slain by no mortal weapon, and that the fires were caused by him offering sacrifices to the spirits to raise them to fight alongside him. On the night of the 31st January Ungern assembled his troops. In the medieval tradition, he promised them three lawless days within the city if they could take it. Cold and desperate, his men fell upon the city and smashed through the Chinese defences. Throughout the day and on into the night there was bloody fighting in the streets, and by the small hours of the morning the Chinese forces were on the run. Then the killing began.

It began with looting, both of valuables and of alcohol. Banks were broken into, and soldiers lined up to get their share of the spoils. Drunken soldiers fired their weapons into the air, and one Cossack who turned his gun on his comrades had to be killed. Then the mood turned bloody. As the Russian civilian residents who had been imprisoned and starved were released from the prisons, they fired up the soldiers into a rampaging mob. The Baron’s doctor, Dr Klingenberg, was later named as the ringleader. The target of their anger was not just the Chinese civilians, but was also the city’s Jewish population. There seems to have been no real reason for this, but the anti-Semitism of the Baron’s troops required no reason. Men were murdered, women were raped and then murdered. The officers had no control over their men – one who tried to rescue a girl being assaulted by a gang of Cossacks was shot by his own men. Some Chinese and Jewish civilians sought sanctuary in the embassy of a Mongolian prince named Togtokh (possibly the same Togtokh who had fought in the 1911 Revolution), but the mob forced him to hand them over. For three nights the city burned. Then on the 4th February the Baron brought law back to the city, and those who continued to murder and loot faced death for their crimes. (Crimes committed during the permitted lawless period, of course, went unpunished.) All this meant for the Jewish population was that the disorganised killing was replaced with organised death – the Baron declared an official pogrom, with the objective of killing every Jewish man, woman and child in the city. In this he was unsuccessful – partially due to the Mongol indifference to his anti-Semitism (to them, one foreigner was the same as another), and in part due to the courage of those who smuggled survivors out of the city (Togtokh was able to atone for his failure during the massacre by managing to shelter one group). Yet the slaughter was still immense.

On February 21st, the Bogd Khan was re-established as monarch of Mongolia, and on the 13th of March Mongolia was declared an independent monarchy, with the Baron as military leader (and effective dictator). Ungern had achieved his goals. Yet seizing power and holding onto it would prove to be two different challenges. While the Baron sought alliances with those he considered spiritually worthy (such as the Mongol guerilla leader Ja Lama, who slaughtered the envoys the Baron sent him), those he considered anathema were massing against him. The chaos he had sown in Mongolia was seen as an opportunity by the Bolsheviks, who saw the establishment of a Communist Mongolian buffer state as the ideal way to secure their border. They began raiding into the Baron’s new kingdom, and he determined that the ideal course was to strike back at them in force. He was unaware, however, that the Bolsheviks had successfully pacified Siberia and broken the White forces permanently, and so would be able to bring their full force to bear against him. In addition they had a fully mechanized force, while his army consisted entirely of cavalry. The Savage Division, divided into two brigades, attacked Russia in May, and by June they had been beaten back across the border. The Bolsheviks did not stop there however, and just kept marching on to Urga.

By July Urga was in Bolshevik hands, and the Baron’s troops had returned to the hills. Guerilla warfare was where they excelled, however, and the Bolsheviks found it impossible to trap them. With his troops now numbering around three thousand men, Ungern led them back across the border into Russia. He claimed to have an agreement with Semyenov and the Japanese to launch a joint attack to retake their Siberian territories. Though they met with initial success, the support failed to materialise and they realised that the main Red army was heading to destroy them. With no hope of defeating such a large force, they retreated back the way they had come. At this point, Ungern’s men had lost all heart. They decided to disband, and escape to Manchuria where the majority of White Russian exiles had fled. When Ungern declared his intention to have them fight their way to Tibet, the troops mutinied. On the 17th August they killed Ungern’s deputy, Rezukhin, and forced Ungern to flee from the camp. On the 20th August he was captured by the Bolsheviks.

The Baron went on trial on the 15th September. The proceedings were a formality, as the verdict and sentence were beyond any doubt, but the opportunity to put such a famous monster on the block was not to be passed over. The prosecutor took the opportunity to preach the gospel of atheism, pointing to the Baron as an example of the type of behaviour typical of all religious fanatics. Ungern spoke little, though his calm demeanour and measured speech did somewhat detract from his monstrous image. The trial lasted over six hours, the verdict was guilty and the sentence was death. Most accounts have it that the sentence was carried out that night, though some say that it took place two days later on the 17th. When word of the sentence reached Mongolia, the Bogd Khan (once again reduced to a ceremonial role) had prayers said throughout the kingdom for him. The Baron wore his medals before the firing squad, though he had destroyed his most treasured one, the Cross of St George, to keep it from his captors. Legend has it that a piece of shrapnel from one of the medals flew back and cut open the cheek of one of the soldiers who fired at him. Even in death, the Bloody White Baron was a dangerous man.

Images via wikimedia except where noted.

[1] One of Roman’s ancestors, Otto Reinhold Ludwig von Ungern-Sternberg, was exiled to Siberia as a pirate. He was later accused of luring ships onto rocks and wrecking them, then killing the crew.

[2] He later told his biographer and chief of intelligence, Ferdinand Ossendowski, that his grandfather had converted to Buddhism in India, and that he and his father had both raised as Buddhists. Whether this was actually true is unlikely.

[3] His wife, who took the name Elena Pavlovna Ungern-Sternberg, is notably absent from the narrative once Ungern goes to Mongolia.

[4] There are wild stories that the Bogdan Khan indulged in pansexual orgies, offered his wife out to his favourites and eventually went blind from undiagnosed syphilis. Of course, there are such stories around many rulers, so it’s hard to know if they are true.