Vladislaus Dracula, the Wallachian Impaler

Few outside of Romania and Bulgaria would have heard of their folk hero Vlad Tepes if it had not been for an Irish writer named Abraham Stoker. Bram (as he is more commonly known) was inspired by the tale, and it led to him researching central European folklore, and writing the novel that made Vlad an icon, under the name he is most commonly known – Dracula. How Bram came to know of Vlad is unclear. The most likely story is that he heard the tale from Ármin Vámbéry, a Hungarian friend of his who was a writer, traveller and occasional spy. [1] In contrast to the fond remembrance his countrymen had for him, Hungarian folk memory cast Vlad as a tyrant and a murderer, so terrible that the grave itself could not hold him. From this, Bram created his monster, and made Vlad immortal. But what was the truth behind this tale?

Wladislaus Dragwlya (as he signed his name) was born in 1431 in Hungary, as the third son of a prominent noble also named Vlad. His mother was a Moldovian princess named Cneajna. The year he was born, his father was inducted into the chivalric order of Hungary – Societas Draconistarum, the Order of the Dragon. His father gained the nickname Dragul, or Dragon, and from this came Vlad’s own patronymic – Dragulea, the Son of the Dragon. When Vlad was five, his father inherited the throne of the Principality of Wallachia [2] from his brother Alexander. Wallachia was on the border with the Ottoman Empire, [3] and when Vlad the elder was driven out by rival factions in 1442 he turned to the Turks for aid. In exchange for their support of his return, he agreed to pay them tribute, and sent as hostages the eleven year old Vlad, and his seven year old younger brother Radu. The two boys were educated in logic, literature and history (as well as taught from the Quran), and young Radu became a good friend of the sultan’s son (and future sultan) Mehmed. Vlad, on the other hand, hated the Turks. He hated Mehmed, and so, for his betrayal, he hated his brother as well. There are stories that the young Vlad was victimised by their guard, given the beatings that they felt a foreigner needed to learn respect (and that his brother, as Mehmed’s friend, was immune to). If their intention was to teach Vlad his place under the Turks, they failed spectacularly.

The changing tides of European politics nearly buried the boys five years later, as a crusade was called against the Turks, and Vlad the elder was (as a vassal of Hungary and a member of the Order of the Dragon) called on to take his place in the ranks. He refrained, but sent his eldest son Mircea in his place. However when Vlad allowed the Turks to reoccupy a key fortress in hope of protecting his two sons, the Hungarian regent, a man named John Hunyadi, had had enough. In 1447 he invaded, supported by many of the Wallachian boyars. [4] Vlad the elder was killed in battle, while Mircea was captured by the boyars, blinded with a red hot poker, and then buried alive. Hunyadi was not pleased – he had intended to bring the Draculesti to heel, not to kill them. He was even less pleased when the Turks took advantage of the confusion to invade, putting the sixteen year old Vlad Dragulea on the throne as Vlad III. Hunyadi could not allow the ruler of a Hungarian principality to be a Turkish puppet, and so he invaded once more, driving Vlad out and re-installing the man he had appointed as ruler, Vladislav II.

Vlad took advantage of this situation to escape from the Turks, and fled to Moldovia. There his uncle Bogdan was Prince, and so he was safe – until Bogdan was assassinated in 1451. With nowhere else to turn to, Vlad went to Hungary, and put himself at Hunyadi’s mercy. The fact that he did this rather than return to the Turks impressed John. By this time Mehmed had become Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and Vlad’s hatred of the man was clear. This, combined with his knowledge of the workings of the Empire, made him an invaluable advisor. In 1453 Mehmed conquered Constantinople, which left his armies on the doorstep of Europe. Three years later he laid siege to Belgrade, threatening Hungary itself. John Hunyadi raised an army and relieved the city [5]. In the meantime, Vlad was sent to dislodge Vladislav II, who had been refusing to provide troops to support the defence of the kingdom, and had instead been engaged in border disputes with the neighbouring principality of Transylvania. [6] With the aid of Transylvanian troops Vlad invaded, and slew Vladislav II personally in hand to hand combat. Finally, by his own hand and in his own right, Vlad was prince.

Wallachia had been left in a ruinous state by the neglectful Vladislav, and Vlad was quick to remedy the situation. He sought to strengthen the economy by building new villages and farms, and by placing restrictions on foreign trade. He also took measures to reduce the power of the boyars, mostly by reducing their numbers by having large numbers of them killed. He had not forgotten who had actually killed his father and brother. In place of the feudal aristocracy that he bloodily disposed of, he operated a meritocracy, giving posts normally reserved for nobility to able foreigners, knights and peasants. It is for this championing of the common man that made the people love him – while it was his cruel treatment of his noble enemies that turned those who wrote the histories against him.

In 1459, Mehmed sent envoys to Wallachia, seeking payment of the tribute that Vlad’s father had agreed to pay. Vlad knew that paying the tribute would earn him the enmity of the Hungarian kingdom, and of most of Christian Europe. In addition, he would have been unwilling to pay tribute to a man he hated. So instead he claimed to take offense at the envoys refusing to remove their hats (though he would have been well aware that the Turkish custom was to always cover the head in public), and ordered that their hats be nailed onto their heads. When the Ottoman Emperor received the bodies of his envoys, crude steel spikes attaching their turbans to their skulls, he knew that he could only answer this insult with war. He sent Hamza Bey, the ruler of the formerly Greek city of Nicopolis out with a thousand men. His remit was to ally with Vlad if possible, as Vlad controlled a key stretch of the Danube river for the sultan’s invasion plans. If Vlad showed any hesitation to make peace, he was to be killed. However, Vlad learned of Hamza’s orders and set an ambush of his own, capturing Hamza’s forces in a narrow gorge they were passing through and killing them all, suffering no casualties due to his use of a new innovation in war – handguns. He had all of the Turks posthumously impaled, saving the longest stake for Hamza, in deference to his rank. [7]

Quite how much impalement had been used in Vlad’s reign up until now is a matter of some debate. Later legends clearly exaggerate his harshness towards his own people as part of a general effort to blacken his name. On the other hand, the death penalty was liberally applied in Hungary at the time, and impalement would have been a standard (if not common) method of applying it. It is certain that it became his preferred method of dealing with Turks, and his childhood imprisonment seems to have led to some virulent hatred of the people. This became evident over the winter of 1462, when Vlad and his men began to terrorise the Turkish settlers in Bulgaria. First the military camps were dealt with, usually by Vlad infiltrating them disguised as a Turkish soldier and using his flawless command of the language. Then he would open the camp to his men, and they would burst in and kill all that moved. But it was not just military targets that Vlad went after. In a letter to Matthias Corvinus, the new King of Hungary, he said “I have killed peasants men and women, old and young… We killed 23,884 Turks without counting those whom we burned in homes”. Once again, impalement was his method of choice. In response, Mehmed sent an army of 18,000 men to attack Wallachia and draw Vlad back. This they did, though they suffered heavy losses for it. Vlad scored a crushing victory, leaving over half of the invading army dead. His victories were celebrated throughout western Europe, while in Turkey people actually began to emigrate east, looking to get further away from the European border. Mehmed knew that something had to be done.

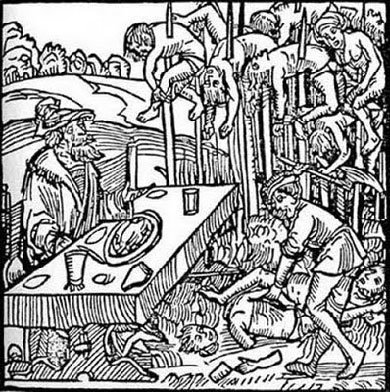

At the time Mehmed had been besieging the city of Corinth, as part of his ongoing conquest of Greece. However he broke off the siege at the news, and sent out across the empire to gather an army to rival that with which he had conquered the ancient city of Constantinople (now the capital of his empire) ten years before. Estimates of the size of the force he assembled range from ninety thousand to three hundred thousand, with even the low number outnumbering Vlad’s army of thirty thousand men. Though Vlad sent desperately to Corvinus for aid, he received nothing but empty promises. The boyars he had treated so harshly had allies in the rest of Hungary, and it is clear the King had no wish to stick his neck out to save the populist leader. Instead, Vlad relied on guerrilla tactics – burning crops, poisoning wells and setting traps for the oncoming Turks. He even sent people infected with disease to intermingle with the oncoming army and infect them, succeeding in sowing an outbreak of bubonic plague among Mehmed’s ranks. Still, the Turks advanced until they camped within a day’s march of Vlad’s capital, Târgoviste. Vlad knew that he had to strike. Once again he disguised himself and went to spy in the enemy camp, learning that Mehmed was enforcing a curfew on his soldiers. Thus he decided on a night attack, and the following night he led a cavalry force rampaging into the camp. How successful this was is a matter of debate. Some historians think it was only a minimal success, while pro-Wallachian accounts at the time have it as a great success, only undermined by the hesitancy of Vlad’s lieutenants. What is certain is that Vlad failed in his primary objective, killing Mehmed. He had misidentified his tent, and instead killed his two grand viziers. The following day, Mehmed led his army to the capital, seeking revenge. But they found it deserted, with the gates lying open. They entered, only to find within the city a forest of spikes. Over twenty thousand Turks, every prisoner that Vlad had ever taken, had been impaled and left on display. The centerpiece, rising above all the rest, was the decayed body of Hamza Bey. Declaring that “he could not take the land away from a man who does such marvellous things”, Mehmed withdrew back to Turkey.

Mehmed did not abandon Târgoviste, however. He left behind him Vlad’s despised younger brother Radu The Handsome, now a devout Muslim. The two brothers fought for control of the country, but Vlad’s lack of support compared with Radu’s inexhaustible source of supplies meant that the end was hardly in doubt. The fact that many of the alienated boyars flocked to Radu’s banner didn’t help. Radu forced Vlad back to the fortress of Poenari, then laid siege to it and finally conquered it. Vlad escaped, fleeing to Matthias Corvinus’ court in Hungary. There he hoped to gain aid in reconquering Wallachia, but instead Corvinus framed him for treason, forging a letter from him to the Turks seeking to surrender. This allowed Corvinus to declare an end to his war on the Turks, abandoning Wallachia and conveniently keeping all the money that the Pope had just sent him to wage war against the infidels. The propaganda he spread at the time to blacken Vlad’s name and lessen his betrayal forms the core of the most infamous legends about the Impaler.

Vlad was not imprisoned for long, as he still had friends at the Hungarian court. In 1465 he married the daughter of his old friend Michael Szilágyi, who had been the King’s cousin. This helped to secure his release in 1466, four years after he had been imprisoned. The king gifted the couple a house in Budapest, where they raised two sons. Alas, it was not to be Vlad’s fate to live in quiet domesticity. In 1475 Radu suddenly died, aged only forty years old, and Vlad immediately set out to reclaim his kingdom. His attempt to raise a revolution against the Ottoman occupiers failed, however, when he was killed in battle less than two months later. The details of his death are unknown, but his head was sent back to Istanbul as a trophy for the sultan.

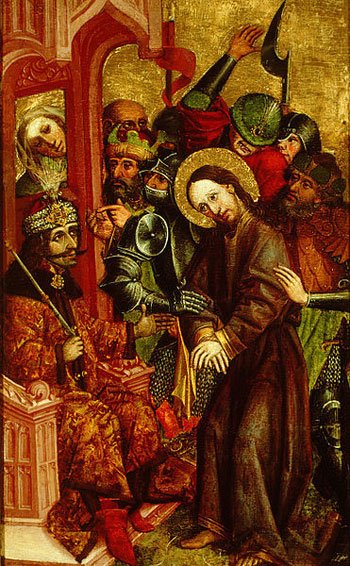

Vlad’s eldest son, Mihnea “the Evil” managed to take the throne in 1508, but was driven out of Wallachia and eventually assassinated outside a Transylvanian church. Others of Vlad’s descendents would take the throne over the next century, but none would ever hold it for long. Meanwhile, Vlad’s legend continued to grow. His features became synonymous with evil, with several budding Renaissance artists adopting them for figures such as Pontious Pilate, or the leader of the centurions arresting Jesus. Even during his lifetime, the German poet Michael Beheim created an epic poem entitled “Story of a Bloodthirsty Madman Called Dracula of Wallachia“. In Russia, too, tales of the Wallachian ruler’s atrocities excited the masses, and grew in the telling. Eventually the legend outgrew the man, and to most of the world he was forgotten. The nineteenth century birth of Romanian nationalism [8] cast Vlad in a different light, with epic poems such as Tiganiada recasting him as a defender of the Romanian nation against foreign invaders, and some even called for Vlad Tepes to come again and sweep away the Ottomans (who still ruled them at this point).

Nowadays, too, it has become a common trope to attempt to rehabilitate Vlad – whether through contrariness, or as part of the modern re-envisioning of vampires (as Vlad has, inescapably, become) as tragic anti-heroes rather than unstoppable forces of darkness. The latest film to be released about Dracula, Dracula Untold, seeks to marry historical truth and vampire legend together – though it remains to be seen if it succeeds in that, or becomes the latest in a long line of films to have the legend overpower the man. There is little of Vlad in the cinematic incarnations of Dracula. Perhaps this new film will be the exception.

Vlad’s ends – defending his homeland, breaking the power of corrupt aristocracy – may have been noble. But his means were horrific, and no noble end could justify the wholesale slaughter he commanded. In the end, perhaps he deserves to be remembered as he is – as a monster, lurking in the dark. Perhaps we’ll sleep better if we don’t remember that he was, like us, just human.

[1] In the novel Dracula, Van Helsing refers to his “friend Arminius, of Buda-Pesth University”. This is almost certainly a reference to Ármin.

[2] Nowadays part of Romania, but in those days one of the highly independent parts of the Kingdom of Hungary.

[3] Modern day Turkey.

[4] A boyar was the highest rank of non-royal noble – equivalent to an English Earl, or a German Count. It is the latter that Stoker translates it to when applying it to Dracula.

[5] The noon ringing of church bells that is now accompanied by the Angelus is said to have originated from the celebration of this victory.

[6] One wonders if Stoker chose Transylvania rather than Wallachia as a homeland for his Dracula simply because the Latin name fits more easily on the English-speaking tongue.

[7] Vlad did not have a monopoly on atrocity, of course. Earlier in the year his friend and future father in law Michael Szilágyi had been captured by the Turks in battle, and had been tortured and then sawed in half. It was the scale of Vlad’s actions that made him infamous.

[8] Not too dissimilar to the Celtic Revival that Yeats and others would foster fifty years or so later.

Greetings from San Antonio, Texas. It was mentioned at the beginning of the article about Prince Vlad Tepes (Dracula) that outside of Romania and possibly Bulgaria the truth about this individual is not that well known. Dracula has supporters in TEXAS in the cities of Comanche TX, where I grew up, and also in Austin and San Antonio, where his case has been defended and his name has been cleared. I have worked toward setting the record straight about all this since the year 1958, when I was btw. 12 and 13 years of age. There is a Romanian festival held here in San Antonio each October, in which Dracula is spoken of in an honorable way. I have found this all to be inspiring. There are some similarities with Texas history and Romanian history, especially when Vlad Tepes (Dracula) is factored in. — Cheryl B. Montoya