William Brodie, the Man With Two Lives

William Brodie was born into one of the most respectable families of 18th century Edinburgh, but to say he wound up the black sheep of that family would be a gross understatement. Both of his grandfathers were lawyers, while his father Francis ran a highly successful cabinetmaking business that catered to the upper crust of Scottish society. Young William was born in 1741 with the proverbial silver spoon in his mouth. He was raised into his father’s trade, and showed an aptitude for it that boded well for the firm

Indeed, when Francis Brodie died in 1780 he seemed to leave his son set up as one of the pre-eminent businessmen of the city. William inherited ten thousand pounds, a good sum in those days, along with a house and workshop on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile. While the Brodie clan had in the past been embroiled in rebellion, fighting for the Covenanters against the Crown, William was loyal to the government. He was a member of the Edinburgh Cape Club, an association originally founded to help organise an Edinburgh militia but which had by his time devolved into a social gathering. Among his fellow members were the painters Alexander Nasmyth, Alexander Runciman and Henry Raeburn (one of the finest Scottish portrait painters, who would go on to earn a knighthood). Another famous member was the poet Robert Fergusson, who died in 1774. It was through Fergusson that William is said to have met Rabbie Burns, the quintessential Scottish poet. The president of the club (known as the Sovereign of the Cape) was the folklorist David Herd. The club had connections to some of the most influential members of Scottish society – for example, Herd was friends with, and Raeburn famously painted, Sir Walter Scott. Membership in this society indicated William’s prestige, but it was far from the only such indicator. By 1786 he had become the Deacon of the Incorporation of Wrights, which is to say, head of the city’s guild of craftsmen. This entitled him to a seat on the city council, and put him right at the top of respectable Edinburgh society. But as he sat with his fellow councillors, none of them really knew the man they had brought into their midst.

In many ways, William Brodie epitomizes British society of the 18th and 19th century – outwardly respectable to a fault, but underneath the surface, boiling with corruption. Edinburgh was a city with two faces, both the respectable Scottish capital and centre of learning and culture, and the home to the tottering wooden tenement blocks that would burn away in 1824, when the Great Fire of Edinburgh raged across the city and left scorch marks still visible to this day. William Brodie had a foot in both sides of his city, for while he was seen in the homes of the great and the good he was also well known (though discreetly so) to the darker side of the city. There he gambled and drank and indulged in all the vices available (he kept two mistresses, and had five illegitimate children). But if that was all, he would have been no different from dozens of other men who had similar discreetly indulged appetites. No, William’s duplicity ran deeper.

It was the gambling that was the problem. Green baize and playing cards were many a man’s ruin, and the gambling houses of the 18th century were purpose made to take men like William and fleece them right down to the bone. It was later claimed that William got into debt with some very dangerous people to finance his gambling habit, and that this was what prompted him to turn to crime. This was in 1768, when he was 27 years old and still working for his father. They were installing furniture in a bank in the city, and William took the opportunity to copy the bank’s keys. He then returned late at night and stole £800 – a significant sum. Whether or not this was enough to clear his debts, the lure of easy money had its hooks into him. The late night robberies became a regular Edinburgh mystery for the next twenty years.

By the 1780s, William’s criminal enterprise had become a regular part of his life, and he had partnered up with an English locksmith called George Smith, who was able to create copied keys from the impressions William made. In 1786 William expanded the operation, recruiting a thief named John Brown (who appears to have also used the name Humphrey Moore on occasion) and a shoemaker named Anthony Ainslie. With this crew he started doing bigger and bigger jobs, until 1788 when he fatally overreached himself with a scheme to rob an Excise Office. Back in those days of the cash economy, tax offices such as this would hold large sums in virtually untraceable currency – a rich prize, but a risky one.

From the trial records, it appears that on the 30th November 1787 they used copied keys to enter into the office between the time it was closed and the arrival of the night watchman. They tried to force open the door to the inner cashier’s office, where most of the money was kept, but were not able to do so with the tools they had on hand. On leaving they found their copied key would not lock the door, and so they had to leave it open (and therefore put the office on guard). It was four months later, on the 5th March 1788, that they returned to the office. They were armed, and Brown later told that William, when preparing his pistol, quoted the Beggar’s Opera:

Let the Chymists toil like Asses,

Our Fire their Fire surpasses,

And turns all our Lead to Gold.

Earlier that day they had stolen a coulter (one of the blades from a plough) which they used to force open the door. They looted the office, and managed to find the relatively paltry sum of sixteen pounds or so. In fact, there were six hundred pounds locked in a desk drawer, and the key was sitting on the desk, but the fact that the keyhole was concealed by a flap was enough to prevent them from managing to unlock it. They were disturbed by a deputy solicitor who had to pick up some papers from his office above the premises being robbed. Brown and Smith nearly shot him, but instead let him escape unmolested and unsuspecting of the peril he had escape. This may have spooked them into abandoning the robbery without the biggest prize, [1] and John Brown decided that this debacle was the end of the line for him. One of the gang’s previous robberies had provoked the government into offering a free pardon (along with a reward) to anyone prepared to give information on it, and Brown took advantage of this. That very night he went to the Sheriff’s office and turned himself in.

Brown was canny enough to realise that levelling accusations of burglary against a city councillor was a good way to get himself ignored, and so he initially only laid charges against Smith and Ainslie. Still, when they were arrested William realised that his luck had run out. He immediately fled, discreetly, to London and from there to Amsterdam. While on the boat from Leith to London (using a fake name) he gave some letters to a man named Thomas Geddes from Edinburgh to deliver for him. By the time Geddes got to Edinburgh, however, both Brown and Ainslie had given William’s name to the authorities. His absence (and some previous evidence pointing to him) had led them to issue a description of him and Geddes recognised the “Mr Dixon” who had given him the letters. After some consultation, he delivered them to the sheriff, and they contained enough incriminating material to prompt a search of William’s house. There they found burglary tools and items known to be stolen, including a ceremonial solid silver mace which had been stolen from the College of Edinburgh the previous autumn. This led to an immediate order being issued for William’s arrest, and he was traced to Amsterdam. He had just completed arrangements to cross the Atlantic to the newly independent United States of America, where he would have been safe from the law, when he was arrested.

To say the trial of William Brodie was a major event would be an understatement. The revelation that such a pillar of the community had been leading a double life for decades was earth-shattering, and despite the evidence against him some found it almost impossible to believe. However Ainslie and Brown’s evidence, backed up as it was by the corroboration of many respectable citizens, was enough to convince the jury to convict. Brown’s ability to give evidence was disputed, as the defence had discovered he had previously been sentenced to transportation and illegally returned. This was actually a lucky break for Brown, as the judge ruled that his pardon extended to cover this earlier crime. As if in gratitude, he was the star witness for the prosecution and was erudite enough to earn a compliment from the judge. After the verdict was returned, the Crown entered into evidence a confession which Smith had made, but later recanted. While this was inadmissible as evidence in the trial, once it was completed they wished to preserve it for posterity. These contained the accounts of numerous robberies the gangs had committed, including stealing the silver mace from the college. With this evidence on top of the guilty verdict, even William’s closest friends realised his true nature.

William Brodie and George Smith were hanged on the 1st October at the Edinburgh Tollbooth, in front of a huge crowd. The hanging became the centre of many legends, as did most of William’s story. One story had it that he had designed the gallows he was hung on himself, which would have been quite a departure from his cabinet-making trade. A slightly more plausible version was that he had helped improve the mechanism of the trap-door. The most bizarre rumour, however, was that he managed to survive being hanged. Supposedly he had managed to conceal an iron collar beneath his clothes, and make an arrangement with the hangman and the doctor on duty to have him swiftly declared dead. One version of the story had it that this succeeded, another that it failed and the drop broke his neck, a third that he was temporarily killed but revived by the doctor. In those versions where he survived, the story had it that he fled to France, with his family soon following after. In truth, this seems the most implausible part of the tale – that a wife who had just had her husband’s infidelity declared in court would be willing to follow him. Regardless, the boring reality seems to be that William was executed in accordance with his sentence and that he was buried in an unmarked grave that is now beneath a car park.

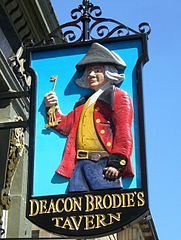

William may be gone, but he is far from forgotten. The Deacon Brodie Pub on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh bears witness to how his story has become part of the strange tourism culture of that city, which seems in large part to consist of celebrating what a terrible place it was to live in centuries ago. But his story has reached far beyond Edinburgh, albeit in somewhat mutated form. The author Robert Louis Stevenson, born in 1850, grew up hearing stories about Brodie. His father owned some furniture that Brodie had made, and the stories he told of it inspired his son as a teenager to write a play about the man called “Deacon Brodie, or The Double Life”. While this early work was a failure, the core idea – of a man who lived an apparently virtuous life, but who concealed a darker inner self – stayed with Stevenson, and grew, and eventually blossomed into a nightmare in 1884, of a man physically transforming into his more evil half. With the nightmare boiling in his head, Stevenson wrote like a fiend and within three days the first draft of “Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde” was written. The novel, of course, went on to be a great and influential success. And the idea that William Brodie spawned – of a monster among us – became part of the narrative of the world.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] There was a later story that William had been on watch and dozed off, leading to them nearly being caught. However the trial records show that it was actually Ainslie who was on watch, with a whistle to warn of anyone approaching. They also explode the myth that the robbers were caught red-handed and forced to flee, and that Brown was caught and forced to confess.