William McGonagall, Professional Bad Poet

William McGonagall of Dundee was often cited as the worst poet ever to make his living in the trade. He was, according to the census of 1841, born in 1825 or 1826 somewhere in Ireland. His parents were definitely both Irish immigrants, but William himself claimed to have been born in Edinburgh and brought up in the Orkneys. This inconsistency could be down to either a mistake on the census form (not unknown), or McGonagall’s own belief that he would suffer prejudice if he self-identified as an immigrant. From that same census it appears that his family had moved to Dundee sometime in the four years prior to 1841, and that William was, like his father, earning a living as a hand loom weaver. In 1846 he married a woman named Jean King, whose mother was also an Irish immigrant.

William and Jean had six sons, and two daughters. The youngest, Thomas, died in infancy in the 1870s but the others all grew to adulthood – an impressive feat for the time. William gained a reputation as somewhat of a “character” in Dundee. His initial passion was for acting, and he became infamous for his performances at the the Theatre Royal in Dundee. He made several appearances there, though the first and most famous was his appearance as Macbeth in the December of 1858. It’s been suggested that he only got the part by financing the production out of his own pocket, which would suggest that his trade (now classed in the census as “Carpet Weaver”) was paying him well. The play drew a large audience, possibly more out of anticipation of a trainwreck than anything else. A trainwreck was exactly what they got – McGonagall became convinced the actor playing Macduff was trying to upstage him, and refused to die in the climactic sword fight. The audience, of course, lapped it all up. McGonagall, in his autobiography, claims that he received a standing ovation. Thereafter he was “managed” by a local impresario named Forrest Knowles, who had him play Hamlet, Othello and Richard III in later productions.

William’s stage career never amounted to more than a hobby, but it was in June 1877 that he found his true vocation. By his own account he was sitting in his back room when an irresistible compulsion to write a poem came over him. Unable to resist the urge, but unable to think of a subject, he eventually settled on a preacher he had admired (and who, probably not coincidentally, was known as a champion of working-class poets). He wrote a poem in praise of the man, which began:

Rev. George Gilfillan of Dundee

There is none can you excel.

You have boldly rejected the Confession of Faith,

And defended your cause right well.

The poem written, he sent it off to a local newspaper. They published it on their letter page, with a rather ambiguous comment that it was a “a sample of [William]’s powers of versification”. William, however, took the publication as a ringing endorsement of his poem. [1] Gilfillan is said in William’s autobiography to have commented “Shakespeare never wrote anything like this”. Indeed. Alas, William’s hopes of winning his patronage were dashed in August 1878 when Gilfillan suddenly died. William, who had by this stage written his second poem, The Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay, decided to set his sights higher and seek out a new patron: a Royal one.

Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay !

Which will cause great rejoicing on the opening day

And hundreds of people will come from far away,

Also the Queen, most gorgeous to be seen, [2]

Near by Dundee and the Magdalen Green.

McGonagall first sent a letter, along with his poem about the bridge, to the Queen. In response he received a reply thanking him for it, almost certainly a standard form letter for replying to such submissions. To William, however, it was a ringing endorsement, and his first collection of poems (a tuppenny chapbook, containing the two poems mentioned and two more) was named Poetical Pieces: Poems and Song by William McGonagall, Poet to Her Majesty. It did occur to William, however, that if he was poet to her majesty he should give her a personal reading. Luckily for him, the Queen’s famous residence at Balmoral was only fifty miles or so from Dundee, and so he set out on foot to present himself to his patron.

On the Spittal of Glenshee,

Which is most dismal for to see,

With its bleak and rugged mountains,

And clear, crystal, spouting fountains

With their misty foam;

And thousands of sheep there together doth roam,

Browsing on the barren pasture most gloomy to see.

Stunted in heather, and scarcely a tree,

Which is enough to make the traveller weep,

The loneliness thereof and the bleating of the sheep.

The trip took William north through the village of Alyth, and then through the Spittal of Glenshee, the foot of a valley where several streams combine to form the River Shee. The trip took him three days, and though in Alyth he was able to secure lodgings, at Glenshee he was forced to rely on charity. The respect he got when he introduced himself as “the poet McGonagall” and showed them one of his books was a big boost to his self-esteem. It was on the afternoon of the third day that he reached Balmoral, where unsurprisingly he was denied entrance. When he showed the guard at the gate his book of poems, the guard was unimpressed and simply told him that Lord Tennyson (who had been Poet Laureate since 1850) was the Queen’s Poet. William was sent on his way, and warned that if he returned he would be arrested. At first he thought he would wait at the road and hail her as she passed out, but the threat of arrest cowed him and he decided to return home. On the way back he managed to sell a few copies of his book of poems, which helped to replenish his funds as well as making sure those he met remembered him. When he returned to Dundee a local reporter interviewed him about the trip, and the story (accompanied by some of his poems) made him somewhat of a local celebrity.

The fame helped him make the jump from weaver to professional poet in the 1881 census, though the census taker (who may have read his work) chose to put it in quotation marks. (This also became a common practice in the newspaper reports on his exploits.) His career move may have been necessity rather than choice, as growing industrialisation was gradually driving out hand weavers like him. Though he wrote on a wide variety of subjects, and was always distressingly prolific, his speciality soon became poems lamenting some disaster in the news. This was triggered by a terrible railway accident, when the bridge he had earlier rhapsodised about collapsed while a train was crossing, causing ninety deaths. In response, McGonagall wrote The Tay Bridge Disaster.

So the train mov’d slowly along the Bridge of Tay,

Until it was about midway,

Then the central girders with a crash gave way,

And down went the train and passengers into the Tay!

The Storm Fiend did loudly bray,

Because ninety lives had been taken away,

On the last Sabbath day of 1879,

Which will be remember’d for a very long time.

His professional activities at first seem to have consisted mostly of travelling to the surrounding villages and giving readings of his own poems mixed in with literary classics (such as those of his favourite playwright, Shakespeare). This was a reasonable method, as entertainment was in short supply in those places. It was not without danger though and on at least one occasion an attempt was made to mug William and steal his takings. His outspoken attitude and ferocious advocacy of the evils of drinking were also guaranteed to rub his usual audiences the wrong way. Later in his career William got a position reading his poems at a circus (possibly through the aid of his old friend Forrest Knowles, who was still active in the local entertainment circuit). There are reports that the audience were permitted to pelt him with flour and eggs in retaliation for his poems, though this may be a later invention. It is definite that his performances were so riotous that in 1893 the authorities actually banned them, something he write a poem in protest about.

Fellow citizens of Bonnie Dundee

Are ye aware how the magistrates have treated me?

Nay, do not stare or make a fuss

When I tell ye they have boycotted me from appearing in Royal Circus,

Which in my opinion is a great shame,

And a dishonour to the city’s name.

In fact, he was so distressed at this that he threatened to move away from Dundee entirely. This was not the first time he had contemplated leaving – as early as 1880 he had visited London to see if he could find an audience there, without luck. Even more notably, in 1887 he took a trip to New York, sponsored by the Dundee Courier. [3] There he spent five weeks, hosted by Dundee émigrés, but was unable to get any of the theatres to let him perform his poems. This he attributed to local prejudice against British artists. Overall he found the city itself impressive, but was less happy with the locals who he regarded as drunk, uncouth and with no respect for the Sabbath. In the end, having expected but failed to earn enough to pay his passage home, McGonagall was forced to write to Alexander Crawford Lamb, a noted Dundee art collector and sometime patron of his, begging for him to arrange passage home. Lamb did so, and also sent him a gift of money to equip himself for the trip and purchase mementos.

It was actually in 1894 that McGonagall finally left Dundee, moving first to Perth and then on to Edinburgh. It was while McGonagall was living in Perth that he received a letter (sent care of the office of the “Weekly Scotsman”) purporting to be from “King Theebaw” of Burma, (more correctly known as Thibaw Min [4]) inducting him into the Holy Order of the White Elephant as “Topaz McGonagall”. This was, of course, an obvious spoof. However McGonagall was delighted to receive the royal recognition he felt he deserved and hereafter he had his name written on his books as “Sir William Topaz McGonagall, K.O.W.E.B.” (Knight of the Order of the White Elephant, Burma). In fact, he even used the award as the final incident in his 1894 biography, which he released shortly after he moved to Edinburgh.

At first Edinburgh was welcoming to William. He held matinee readings in Waverly Hall, and was introduced to theatrical celebrities such as Henry Irving, Ellen Terry and Bram Stoker. Gradually the novelty wore off, though he still made a good living for a few years off those who wanted to come and see if his poetry really was as bad as the stories painted it. In 1897 he published a “Jubilee Edition” of his poems, in honour of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee. There does seem to have been a genuine affection to the mockery – when a group of young men from Perth calling themselves the Perth Lyric Club hired him to come up for a “roast”, they were called out for making fun of him in the letters column, and labelled “consummate asses”. Another correspondent rose to their defence, pointing out that William had been well paid, kindly treated and accommodated for the night, adding:

There is no doubt that the poet’s recitals were received with cheers, derisive and otherwise, but if man is paid for making fool of himself he is surely no more than the clown at a circus who is the butt of the jokes, and who enjoys the experience Why? Because he gets paid for it.

It’s never entirely clear how much William was in on the joke, really. While he does seem to have taken himself very seriously, it’s hard to see how he could have missed the reception his poems received. Indeed, he played it up – wearing full Highland dress, and accompanying the livelier pieces (such as The Battle of Bannockburn, a crowd favourite) with much waving and thrusting of a sword. Perhaps he was simply playing a part – an extension of his old theatrical hobby. If so, he had a willing co-conspirator in the media, who were more than happy to play up his “eccentric delusions”. On the other hand, it’s equally possible that he believed himself “the People’s Poet”, unappreciated by the establishment but clearly loved by the general population.

William McGonagall died in Edinburgh in 1902, aged 77. He had been suffering from bronchitis (as will as tinnitus) for some time. His son John had been arrested for theft just a few days before (he was let off with only a few weeks in jail), and this stress may have been the last straw for William. His final poem was about the coronation of King Edward VII, son of the great Victoria. In a way, it seems fitting that the “Poet to the Queen” should follow her so closely. The Dundee Evening Post seems to have summed up the common feeling in its obituary:

Now that the poor old man is gone, I have no doubt that many of his thoughtless tormentors will sincerely regret that they did not show him more kindness.

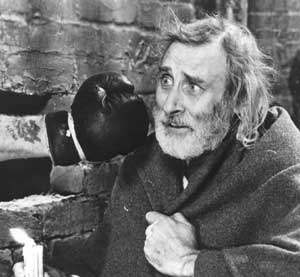

McGonagall was not totally forgotten, after his death. His works continued to sell, through curiosity as much as anything else. It was in 1931 that he actually achieved some real fame, through a passage in In Search of Scotland by the great travel writer H V Morton. In it Morton praises McGonagall’s works as “the perfect bedside book”, to distract one from the cares of the day with a smile. Far from “the worst poet”, Morton declares him ahead of his time, with “that splendid disregard for the decencies of literary formulae which has in recent times made many large fortunes”. It was after this praise that William’s works were returned to print, and it may be this which brought him to the attention of one of his most famous admirers, Spike Milligan. Milligan, of course, shared “that splendid disregard” and in fact seems to have built a great deal of his career on consciously applying that which made McGonagall’s works so amusing. Not only did he name one of the recurring characters in The Goon Show after “the People’s Poet”, he would give readings of his verse – in, of course, the appropriate dress. In 1974 he played William in a fictionalised comedy biopic, The Great McGonagall. McGonagall became a favourite “obscure reference” for many other comedy greats – Monty Python’s Flying Circus featured a terrible Scottish poet, for example, while The Muppet Show actually had a muppet modelled after the poet named Angus McGonagle (the Argyle Gargoyle). [4] In the writings of Terry Pratchett, the battle poets of the Wee Free Men, who torment their enemies with terrible poetry, are named “Gonagles” (which, Pterry has confirmed, is a reference to the “Poet”). His name was also borrowed by JK Rowling for one of her characters, simply because she liked how it sounded. So it is that over a hundred years after his death, Sir William Topaz McGonagall (K.O.W.E.B.) remains unforgotten – proof that lack of talent is no barrier to success, with enough enthusiasm.

Banner via Leisure and Culture Dundee.

More of William McGonagall’s work can be found at McGonagall Online.

[1] Historical psychoanalysis is generally an exercise in futility, but some writers have suggested that William’s inability to pick up on nuance may have been due to some level of autism.

[2] In actual fact the Queen was invited to the opening but declined the invitation.

[3] The local newspapers always got plenty of copy out of William’s antics – for example, when one local company gave him a free tweed suit as a publicity stunt, and then had the gall to insist that they get some publicity out of it, the ongoing back and forth went on for months.

[3] Who had actually been forced to abdicate by British forces nine years prior to this.

[4] He was a prospective guest on the show, until he was preempted by the cast of Star Wars.