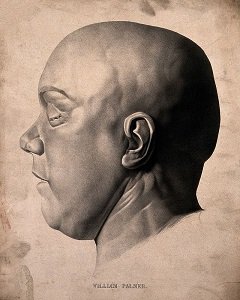

William Palmer, Prince of Poisoners

William Palmer, known to his doting mother as “Billy”, was born in Staffordshire in 1824. His father Joseph was described later as a sawyer, though it seems that meant that he actually owned his own lumber business. And it was a profitable business too. When he died in 1837 he left a sizeable inheritance to his wife and children. All seven of his children (William, aged only 12 at the time, was the sixth) were left £7,000 each, provided they did not marry before they turned 21. The remaining £26,000 was left to his wife Sarah, on the condition that she not remarry. This condition she fulfilled, though there is some evidence she did have at least one relationship after his death. [1]

Mrs Palmer was an overly indulgent mother at best, and William (by some accounts, her favourite) was completely spoilt. This seems to have given him a predisposition towards selfish crimes. In his first job, at a local chemists, he was found to be opening the post they received and stealing money which was sent to them. Only his mother’s profuse apologies (and refunding of the money) saved him from being charged. This seems to have blunted any effect being caught might have had on William, as in his next job (as an apprentice to a village doctor named Tylecote) he was once again caught embezzling and fired. [2] Another incident at this time shows that it wasn’t only money that would prompt William to break the law. When a fellow apprentice started stepping out with a young lady that William fancied, he retaliated by “borrowing” some acid from the chemists and dousing the young man’s possessions in them, destroying them.

In 1844 William registered as a pupil at Stafford Infirmary, in order to try and complete his medical studies. Even at the time his interest in drugs and poisons was noted. The following year he received his inheritance from his father and moved to St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, but the temptations of the big city were far too much for the weak-willed Palmer, and it became clear he would squander the money and fail to receive any qualification. His mother then stepped in and hired a special tutor, promising him £100 if he got William, by hook or by crook, through his entrance exams. This the tutor somehow managed, though later events may have made him regret it.

William returned to Staffordshire a doctor in 1846. One curious event happened a few months after his return, which many people gave a much more sinister interpretation in hindsight. William was drinking in one of his regular pubs, the Lamb and Flag in Little Haywood, when he got into conversation with a plumber named George Abley. The conversation turned into a wager on whether Abley could drink two tumblers of brandy. William had taken to gambling during his time in London, and he was by now unable to resist a wager. Abley succeeded in the bet but became rather ill and was later found unconscious outside. He was carried home, but by the next morning he was dead. The coroner’s jury ruled death by misadventure, though one juror (who knew William) was convinced that he had contrived the incident to revenge himself on Abley after Abley’s wife had rejected his advances. Whether this was true, and if so William had spiked Abley’s drink with some drug or poison, is impossible to say.

While he had been working for Doctor Tylecote William had worked treating pupils at the local schools, and he had made the acquaintance of a teenage girl named Annie Thornton. Annie was the illegitimate daughter of an army Colonel named Brookes who had died several years earlier and left her property worth £250 a year – a respectable sum. Unfortunately Annie’s mother Mary was an alcoholic and so she had been made a ward of the state, which was what he resulted in her being at the school. In 1847, shortly after Annie’s twentieth birthday, she and William were married, and moved to a house in Rugely. It seems to have been a happy enough marriage, and Annie was grateful that William didn’t seem to be dissuaded by the stigma of her illegitimacy. His relationship with his mother may also have been something she found worthy of note – her own relationship with her mother was far more strained. William’s relationship with Mary Thornton was far worse – she accused him of poisoning her cats, and of having married Annie only for her money. On the sixth of January 1849 William brought Mary from her house to his, claiming to have found her unconscious and suffering from alcohol poisoning. Mary never regained consciousness, and died twelve days later. Though Colonel Brookes’ will had said that the property he gave her would pass to Annie on her death, the Chancery Court ruled that her marriage invalidated that clause and the property went to the Colonel’s cousin. William was reportedly “furious”.

By 1850 William had become a noted enthusiast for horseracing. On one occasion he and a friend of his named Leonard Bladen went to Chester Races. William lost on the races but Leonard did rather well. He was in fine form when they left the races, all the more so because William owed him money and had told him he could come back to the house in Rugely to collect it. Leonard wrote to his wife telling her of his good fortune, and claiming that he would come home with close to £1000. Unfortunately while in Rugely Leonard fell gravely ill. He had been hit in the chest by a cart and severely injured six months earlier, and William (being a doctor) declared that this was the result of lingering effects of these injuries. Leonard’s wife came to his bedside, and found him in severe agony. Soon, he died. The death certificate William wrote up listed the cause of death as an internal abscess which was caused by his earlier injuries. Leonard’s wife was somewhat surprised to find that the promised money was not in Leonard’s possession when he died – she found only £15 among his effects.

William’s first child, a son also named William, was born in 1850. He was the only one of William’s children to live past infancy. His four siblings all died, the eldest at two and a half months and the youngest at only seven hours old. All the death certificates list the same cause of death: “Convulsions”. One modern theory is that William had Rhesus positive blood, while his wife was Rhesus negative. If this was the case then any of their children who were Rhesus positive after the first would have been affected by antibodies in the mother’s system and suffered from severe illness. On the other hand, it is unlikely that all five of their children would have been Rhesus positive – and the symptoms described for the children do not seem to match with that of Rhesus disease. One person who loudly declared an opposing theory was the Palmers’ cleaning lady Matilda Bradshaw, who loudly quit their service after the fourth death. She was heard declaring in the local pub that Doctor Palmer had “done away” with another of his children, in order to avoid having to pay to bring them up.

The constant tragedy may have had an effect on Annie Palmer, and William seems to have found it prudent to insure her life for £13,000. He had only made a single premium payment when tragedy struck once again. Annie went to a concert in Liverpool with William’s sister Sarah, but caught a chill in the carriage. On returning home she took to her bed. The next morning William brought her a light breakfast, but she soon began vomiting. She became more and more ill, and less than two weeks later, on the 29th September 1854, she died. The cause of death was given as “cholera”, and there was an epidemic of it in England at the time. [3] William was reportedly “heartbroken” at her funeral, though it’s worth noting that almost exactly nine months later, on the 26th June 1855, his eighteen year old housemaid gave birth to his illegitimate son. Five months later, shortly after visiting his father, the infant died.

After Annie’s life insurance money was paid out, William seems to have realised the potential of this type of payment, especially as he was deeply in debt at the time. Reportedly he tried to insure his brother Walter’s life with six different insurance companies for a total of £82,000. Since Walter was a raging alcoholic, there were no bites until William hired a man to dry Walter out temporarily so that he could pass a medical examination. Once again William only paid a single annual premium on the £14,000 policy before he became able to claim. Walter died on the 16th August 1855, but the insurance company (the same one who had insured William’s wife) were not so quick to pay out as they had been before. They sent out two investigators, who soon turned up some troubling facts. That William had ordered the coffin sealed before Walter’s widow could inspect the body struck them as suspicious, as did the fact that William rather than her was the beneficiary. Moreover they discovered that William was trying to insure the life of one of his employees, a man named George Bates, but Bates was unaware that he was trying to do this. (Although conflicting accounts have it that the two inspectors entrapped William into this scheme as a means of testing his honesty, a test he failed.) Bates was not insured (possibly saving his life, as some would later see it), and no money was paid out for Walter’s death.

In November 1855, William and a couple of friends went on a trip to the Shrewsbury Races. One of these friends, John Parsons Cook, did very well and won nearly £3,000. William had a much less pleasant time, especially as he got a letter from a moneylender reminding him that he owed the man a great deal of money. Still, he went along to Cook’s party to celebrate his winnings. At one stage during the evening a woman attending the party found him in the pantry fussing with a vial of liquid and a tumbler, though he acted as if nothing was amiss. Later in the evening Cook complained that his brandy was burning his throat, though William rubbished the complaint. The next day Cook was unwell and stayed in the hotel, while William lost heavily at the races. That evening they returned to Rugely and Cook booked a room in a hotel across the road from William’s house, so that his friend the doctor could attend to him. Cook’s condition fluctuated over the next few days, improving and then worsening when he ate. One chambermaid also took ill, apparently after tasting some of the broth William had prepared for him. Treating his friend was not the only favour William did for him – he also went to visit the bookies and collected Cook’s winnings for him. Sadly only a couple of days after he returned Cook passed away, in a fit of severe convulsions.

Unfortunately for William, the day after Cook died his stepfather William Stevens showed up. Stevens was a retired merchant, a hard-nosed man who had not been happy about his step-son’s dissolute lifestyle. He took an instant dislike to William Palmer, which wasn’t helped by him finding out that William had already ordered a coffin and was arranging the funeral. William then told Stevens that Cook was responsible for around £4000 in debts, which Stevens replied to by saying that his step-son’s estate would not even be worth four thousand shillings. When he heard of Cook’s winnings and asked William for the betting papers (not knowing he had already cashed them in), William told him that Cook’s death would have rendered them void. When Stevens insisted, William told him that they had been lost. This was the final straw, and Stevens headed to London to consult with a solicitor.

Stevens was, as next of kin, able to insist on a post-mortem. The post-mortem was carried out by a friend of William’s, who reportedly regarded it as a mere formality and turned up to perform it without any medical equipment. At Palmer’s suggestion it was then transformed into a training exercise for two local assistants, one of whom was so nervous he had to be given a drink of brandy before carrying it out. The stomach contents (which Stevens had insisted should be sent to a toxicology expert in London) were allegedly tampered with by William, and the expert (Doctor Alfred Swaine Taylor) was so unhappy with the condition of the specimens that he demanded a second post-mortem. This (testing on less useful samples) found nothing. Still, Taylor attended the coroner’s inquest and gave his opinion that Cook had been poisoned with strychnine. William made the fatal blunder of trying to bribe the coroner, who was an honest man and revealed the attempted bribe to the authorities. William also bribed the local postmaster to give him the results of the second autopsy, but the man was caught and sentenced to two years in jail for interfering with the mail. It may have been these two mis-steps, rather than the evidence (which was largely circumstantial) that led to the coroner’s jury finding that Cook had met his death through being poisoned by William Palmer.

The idea that a doctor was actually a serial poisoner fascinated and terrified the general populace, and a media feeding frenzy started. Every incident from William’s life was scrutinised, every chance acquaintance was interviewed, and every potential piece of evidence had been aired in public a dozen times over before William set foot in court for his trial. It is from this media storm that many of the wilder stories and legends of his life spring, and he was soon dubbed the “Prince of Poisoners”. The fire was fuelled by the trial on the 20th January of William’s mother Sarah Palmer for fraud. She was being sued by a creditor for £2000, but said that she had not signed the document in question. When William was called, he told them that the signature was his dead wife’s, and that he had persuaded her to forge his mother’s name. Sarah was released, and the newspapers had a new story.

Another major story was the exhumation of both Walter and Annie Palmer, on the suspicion that they had also been poisoned by William. Walter’s body (which was sealed in a lead coffin) was found to be so heavily putrefied that a post-mortem was impossible, and in fact the stench from it lingered for months in the unfortunate pub where the coffin had been opened. Annie Palmer’s body was in better state, and Doctor Palmer was able to find traces of antimony, a metallic poison with a similar effect to arsenic and which had been used for slow poisoning of victims since Renaissance times. The coroner’s jury concluded that both Walter and Annie had met their deaths through murder, and these crimes were kept “on the docket” to charge William with if he was acquitted of Cook’s killing.

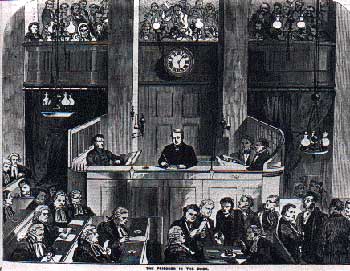

One major problem for the authorities in William’s case was that there was no way they could get an unbiased jury in Stafford. Everyone either knew William, knew one one of his alleged victims, or both. Eventually a new law had to be passed by Parliament, which became known as “the Palmer Act”. This act allowed crimes committed anywhere in the country to be tried at the Central Criminal Court (the famous “Old Bailey”) in London. One month after the act was passed, the trial of William Palmer began.

The prosecution was led by the Attorney General himself, Sir Alexander Cockburn. He was a famous figure, having helped to define the “McNaghten rules” for establishing an insanity defence many years earlier, and would later go on (when appointed as a judge) to become the first Lord Chief Justice of England. Though the failure of Doctor Taylor to find definite evidence of strychnine poisoning was a blow to the prosecution case, they still assembled a great load of circumstantial and supporting evidence. Clear motive was shown in William’s gambling debts and in the theft of Cook’s winnings. Opportunity was demonstrated when two different chemists testified to having sold William strychnine and not recorded it in the Poisons Book since he was a medical man. The other suspicious deaths in William’s life were also cited as evidence of “pattern”. The most damning evidence was that Cook’s death had taken place only a few hours after he had taken pills prepared by William, and the evidence that he had interfered with both the post-mortem and tried to bribe the coroner were also telling.

Against this the defence did their best, and the lead counsel (Mr William Shee) never doubted William’s innocence. Their main angle attack was to discredit the evidence that Cook had died of strychnine poisoning, and they had Cook’s own physician there to testify that in his opinion the death was caused by tetanus. But with the scientific evidence so divided, it was the prosecution’s weight of supporting and character evidence that told against William. The defence scored a bad own goal when they put Jeremiah Smith in the witness box to provide an alibi for William against one of the occasions he was alleged to have bought strychnine. However Smith was a poor choice, as on cross examination the prosecution were able to produce the voided insurance policy on Walter Palmer’s life, which Smith had signed as a witness. Faced with the prospect of either implicating himself or denouncing William, Smith wavered enough to do both.

In the end after twelve days of trial the jury took only an hour and seventeen minutes to convict William Palmer of murder. The judge dutifully, and inevitably, sentenced him to death. He also decided that, since the Palmer Act allowed the sentence to be carried out either in London or in the original jurisdiction, that William would meet his fate in Stafford. On the morning of Saturday the 14th of June 1856 he went to the scaffold, still maintaining his innocence to the end. After his death his mother is famously said to have cried:

They have hanged my saintly Billy!

The case of William Palmer, a doctor who had turned to murder (and who may well have murdered his own brother, wife and children) soon became one of the most infamous of the Victorian era. Charles Dickens referred to him as the “greatest villain that ever stood in the Old Bailey dock”, and he (like Charlie Peace) was one of the few real-world criminals to be referenced by Sherlock Holmes in the works of Doyle, as well as getting a nod in pages of Dorothy Sayers. An acknowledgement by these great writers that the Prince of Poisoners was far more malevolent than any of their fictional creations.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] Something the papers seized on with glee as vaguely scandalous. Also printed in the papers (without any real evidence) were stories that her father had got his money through embezzlement and that Joseph Palmer’s lumber yard had made its money through handling stolen timber.

[2] There was a later rumour that the real reason he was fired was that he had been performing illegal abortions. However once again there is little real evidence for this.

[3] Though the “epidemic” was limited to London, and was actually caused by a water pump which an early epidemiologist named John Snow realised was contaminated by fecal matter from a nearby sewer. In defence of the doctors who signed Annie’s death certificate, though, “cholera” was also a catch-all term used by doctors to describe deaths from dysentery or food poisoning, which were common due to poor hygiene and a lack of knowledge of germs at the time.