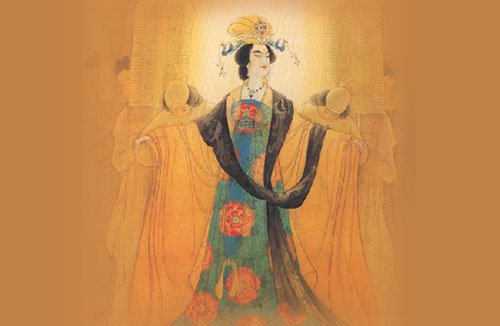

Wu Zetian, the female emperor of China.

Wu Zetian is unique in Chinese history. Had she merely been a powerful Empress, that would have been normal. Had she even been an Empress who ruled in truth through a puppet Emperor, that would have been rare, but not unprecedented. [1] But she was the only woman in the history of the Empire to claim the title of Emperor in her own right – to rule in both name and fact. Needless to say, this made her a controversial figure. There is a saying that history is written by the victors. It’s not quite as simple as that. History is written by victors and losers alike, though the history written by the victors is more likely to survive. But the main point, however, is that history is written by someone. And all of those writers bring their own particular bias to bear. The historians of imperial China were by no means an exception to this rule – in fact, they tended to see history as instructional rather than informative, and their disapproval of a female Emperor tinges all the records we have of Wu Zetian. So while I think that all history should be taken with a grain of salt, I’d recommend that you have some extra grains on hand today.

Wu Zetian (who is usually referred to in the histories only by her surname of Wu) was born under the name of Wu Mei in 624AD to a reasonably well-off but not wealthy family in the imperial capital. She was given a thorough education, which was unusual but not unknown for women at the time, and which would serve her well in later life. At the age of thirteen, her beauty caught the attention of the court officials, and she was claimed as a concubine for Emperor Taizong. It is said that her mother wept when they came to take her away, but Wu consoled her by saying that this was her destiny. Still, her family’s lack of social standing saw her in one of the lower ranks of concubines, in truth little more than a servant (though the Emperor would, naturally, have slept with her at least once). When he died in 649AD she was, as was the tradition with childless concubines on the Emperor’s death, sent to a Buddhist nunnery. There she would normally have been confined to her death, if not for a visit by Emperor Gaozong to the temple that the nunnery was a part of, on the anniversary of Taizong’s death. Reportedly when the two caught sight of each other “they wept” – whether due to being smitten, or because (as some historians believe) Wu and Gaozong had carried out an illicit affair before he became Emperor. Regardless, Empress Wang noticed their reaction, and decided to have Wu brought to the palace as a concubine once more. At the time she was engaged in a battle for the emperor’s affections with Consort Xiao (known as “the Pure Concubine”), and she thought that some distraction might serve her purposes.

This was to prove a critical miscalculation on her part, as Wu soon became by far the Emperor’s favourite. The empress wound up in an alliance with the Pure Concubine in order to try to regain their status. The empress was not helped by the fact that she remained childless, while Wu bore the emperor two sons, followed by a daughter. In 654AD, when this daughter died, Wu accused the Empress of murdering her. Historians are divided as to whether Wang was guilty, whether Wu killed her own daughter in order to make the accusation or whether the daughter died of natural causes. Regardless, it turned the emperor against Wang, and when the following year she and Xiao were found to be trying to use witchcraft (which was illegal) against Wu then the Emperor had them both arrested and detained, demoting Wang and making Wu his Empress. [2] Her son was made heir apparent, and she immediately began using her influence to have those who had supported Empress Wang demoted or executed, and her own family promoted.

It was not all good news for her family, however. Wu Zetian had an older sister, who along with the rest of the Wu family was elevated to the nobility. The sister died, and the title passed to her daughter, who caught the eye of Emperor Gaozang. The jealous Wu, unwilling to allow a rival, had her poisoned and then accused two of her cousins, who had grumbled that accepting promotions simply due to family connection was dishonorable, framed for the crime and executed. This did not harm her standing in the palace, and neither did accusations that her association with a Taoist sorcerer smacked of witchcraft, the same crime that had driven her predecessor from the throne. Instead, her position strengthened, with her being seated next to the Emperor and at the same height (though shielded by a curtain) as he held court. Popular opinion had her as a co-ruler, though rumours also circulated that she was weakening Gaozang with poison (though his health had never been good). In 675 he even considered making her official regent, though he was dissuaded in this. Meanwhile, Wu used her power to eliminate any rivals, including the family of Gaozong’s aunt, and even her two elder sons, who showed far too much independence. The eldest died suddenly, amid rumours of poisoning, while the second eldest (and then heir) was accused of plotting to depose his father and seize the throne. While no direct proof was found, the discovery of a cache of arms in his home was enough to force him into exile, and out of the succession.

In 683AD, aged 55 years old, Emperor Gaozhong died. Wu’s third son was crowned as Emperor Zhongzhang. His reign was destined to be a short one. Influenced by his wife, Empress Wei, he tried to have his father in law made chancellor and to curtail Wu’s power, and she responded by having him deposed and installing her fourth son as Emperor Ruizong. Zhongshang was emperor for a mere six weeks before conceding power, and though Ruizong now ruled in name, people had no illusions as to where true power lay. For six years, Ruizong was a shadow emperor – rarely seen in public, and not even moving into the imperial palace. During this time the Dowager Empress established a powerful network of secret police throughout the court, as well as establishing a system of brass boxes in town centres, where anyone could drop off anonymous accusations against anyone else. She also began a notorious affair with a Buddhist monk named Huaiyi, who was granted several powerful positions in court. Finally in 690AD Wu did the unthinkable. She deposed her son and made herself Emperor.

Prior to this the Wu had been known as Wu Zhao, and it was from this that she named her new dynasty, the Zhou dynasty. By establishing a dynasty and taking the regal name of Wu Zetian, she declared herself the equal of any male emperor. This was in clear violation of the law of the land, but nobody could oppose her. [3] The secret to her success was that she was, despite her ruthlessness, a truly brilliant ruler and the land (if not the court) prospered under her rule. The secret police kept the court in turmoil, with accusations flying everywhere and executions a constant occurrence, but the end result was that no unified opposition to her ever emerged. The secret police were not the only scandal of her reign. Her affair with Huaiyi led into a general fascination with mysticism, as well as a profound respect for the symbols of imperial rule. [3] She elevated Buddhism’s status in the land, at one stage even promoting herself as Maitreya, the Future Buddha, though she drew back from this. And though Huaiyi fell from favour, a succession of other lovers came after. Wu preferred to draw them from the ranks of the commoners (probably not, as salacious rumour suggested, for their stamina; but rather for their lack of allegiance). Two became her especial favourites, the Zhang brothers.

Former child singers, the Zhang brothers began to exercise a great deal of power in the court, and as Wu grew older they began to act as her intermediaries, leading some to speculate that the orders they relayed came from they themselves, rather than her. Their power allowed them to deal harshly with such critics, but in the end they overreached themselves. A coup took place in 705AD, aimed not at Wu but rather at the two brothers, who were killed. The aging Wu, 80 years old at this point, was forced to yield the throne back to Emperor Zhongzhang. [3] She died the following year, and was buried in an imperial tomb, though with the honours of a dowager empress and not an emperor. The monument she had raised to herself, traditionally engraved with an emperor’s deeds after their death, sits blank to this day. [5]

As I mentioned at the start, we should not judge Wu Zetian too harshly. Stories of excessive cruelty and sexual appetite have dogged female rulers, from Empress Irene of Byzantium to Catherine the Great, and as modern scholars have pointed out none of her actions, including maintaining a stable of younger lovers, would have been considered scandalous or even notable if done by a male emperor. (Let’s not forget that Wu herself entered the court as a 13 year old sexual plaything for Emperor Taizong.) Nowadays, she is generally regarded much more sympathetically than she was in her own time. Besides, the Confucian morality of the time held that the laws that governed commoners did not apply to the imperials. Murder was a crime if committed by a farmhand, for example but if murder by an emperor assured the prosperity of the state then it was no crime. All that mattered was that they govern well. This is not to excuse her actions – she waded through blood to take the throne, and then killed without mercy to retain it. But to be ruler of the largest empire on earth took ruthlessness. And in the end there was none more ruthless than Wu Zetian.

[1] The most infamous example of an Empress behind the throne was Lü Zhi, who ruled through her son Emperor Hui. Lü Zhi’s most heinous act was how she treated one of her husband’s concubines, who had tried to get her son made heir. First she poisoned the son, and then she had the mother’s limbs, ears, eyes and tongue removed, before throwing her into a latrine and exhibiting her to her son as a “human pig”. The revelation of his mother’s cruelty drove Hui into alcoholism, allowing her to reign unchecked.

[2] The eventual fate of Empress Wang and Consort Xiao is a matter of some debate. Later histories relate that when Wu heard that the Emperor was planning to release them, she had their hands and feet cut off, then left them to stand in jars of wine until they died, declaring “Let those witches be drunk to their bones”. However, given that even her opponents at the time never made mention of this (and the similarity to the story of Lü Zhi), it is likely apocryphal in nature.

[3] The most striking example of this was her recasting of the “Nine Tripod Cauldrons”, one of the most potent symbols of the early Chinese empire. The originals were forged with metal from each of the nine imperial provinces around 2000 BC, and served as an important part of the imperial rituals for 1800 years until they were lost in the Era of the Warring States. Several rulers would seek to legitimise their rule by casting new copies of the cauldrons down through the centuries. In 2006 the National Museum of China cast their own copies, which are now on display.

[4] He would later be poisoned by his wife, the ambitious Empress Wei, who sought to emulate Wu and rule through her son. The palace guard revolted at this however, and she was killed while Emperor Ruizong, Wu’s youngest son, took the throne.

[5] Like most imperial Chinese tombs, that of Empress Wu has remained undisturbed by tomb robbers or archaeologists. Legend has it that its site was chosen by her husband Emperor Gaozong because the road to it passed between two hills that reminded him of her breasts.