Life or Death Poetry | Anna Akhmatova

This article really gets my goat. As it should. Given that I write poetry. But it might not bother you. You might even find it true to experience. I’m going to explain to you why it’s nonsense. Why entertaining such a claim is a waste of your time.

Maybe you didn’t click the link. That’s no problem. For now you just need to know it’s someone arguing that poetry is dead. Or has at least seen its best days. I come across a claim like this every now and then. Be it in the media or spilling out of some idiot’s mouth. I always wonder how someone can truly consider such. Once you have done even the smallest bit of research, the only conclusion is that poetry is alive. So alive that people suffer immensely in its name. Many even dying.

A poet I have only recently been introduced to is Anna Akhmatova, a Russian Modernist poet. Akhmatova, by all accounts, seems to have lived a tragic life.

She had the great misfortune of living under Stalin’s austere rule. She, like many of her contemporaries, spoke out against Stalin. Against his purges. She suffered greatly for this, as did her contemporaries. Her first husband, Nikolay Gumilyov, was executed under Lenin’s rule by the Cheka. He was a poet and outspoken critic of the Soviet Union. Their son, Lev, was in and out of gulags. Arrested pretty much because of who his parents were.

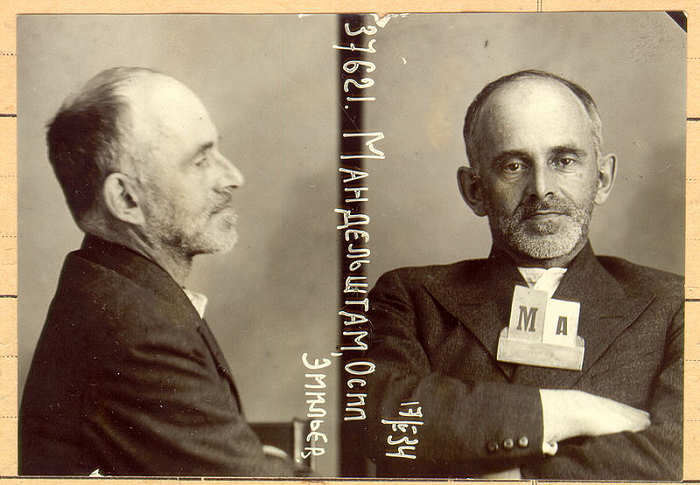

She was ousted from the Union of Soviet Writers. She was slandered and her works suppressed. So much so that many thought she had died. Akhmatova’s close friend and fellow poet Osip Mandelstam died in a Soviet camp. He had written a satire on Stalin, the Stalin Epigram.

Stalin wasn’t exactly chuffed at how he was depicted. So Osip was slung into a gulag. He managed to not get killed that time around. But before too long he was back in the camps. Where he died. Needless to say, Stalin didn’t look too kindly on those who undermined his power.

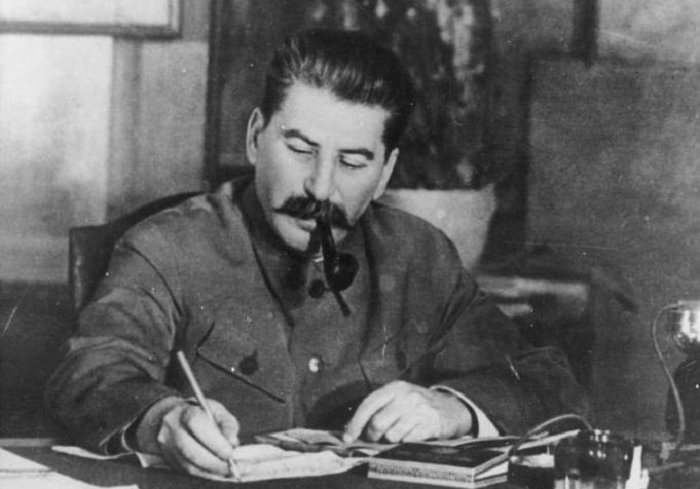

This is Stalin either writing a poem or signing a death warrant.

Still though, Ahkmatova managed to outlive Stalin. She had memorized many of her poems during his reign, for fear of losing them. One such poem being Requiem. She chose to fully publish it once Stalin had died. This was a wise choice no doubt, considering the grizzly fates of her contemporaries. This is arguably her most famous piece. Translations vary. I can recommend Judith Hemschemeyer’s translation from Ahkmatova’s complete poems.

Another of her works worth your time is Poem Without A Hero. One line reads

“I am ready to die.”

The story is that Mandelstam spoke these words to Akhmatova shortly before publishing the Stalin Epigram. She was so moved by these words she fit them into the piece.

I’ll grant you that this is Russia in the past. But modern-day Russia isn’t much different. Consider the imprisoning of Pussy Riot. Outspoken artists suppressed. Persecuted. Under austere rule. I will grant you that they are a punk band, not poets. But isn’t punk another form of expression that’s supposed to have long since died?

Obviously, this kind of suppression is far from limited to Russia or the past. Consider this article on the poetry of Afghanistan’s women. It opens with an account of a young woman beaten badly for practicing poetry. By her brothers. She set herself on fire in protest and died of her wounds. It might seem a bit of a strong move to burn yourself to death. But consider that her only outlet has been taken away from her by her culture.

If you are a poet you might take your ability to write for granted. But depending on where and when you live, it’s far from a given that you can just pick up a pen. Just write. When you like, what you like. If you are not a poet, I can see why you might think poetry is dead or dying. If all you are acquainted with is the pubescent poetry of angsty teens. Or the flaccid imagery of a lot of what can be read on the internet these days. I hope what I’ve detailed for you helps you see poetry in a fresh new light. As a tool, amongst many, for social and political change. As a voice for the suppressed. Not just some throwaway artform that lost its currency long ago.