Aphra Behn, Writer and Spy

Aphra Behn’s origins are mysterious, almost certainly because she wanted it that way. She was born around 1640, probably to parents of the professional class. Her father could have been a man named Cooper. Or he could have been a barber named Bartholomew Johnston, or maybe one named John Amis. Or she might have been the illegitimate daughter of a civil service official named John Johnston, which might explain her reticence about her birth. Or she might have been none of these – Aphra is an unusual name, [1] and one that doesn’t appear in any of the registers or records one might expect. There’s an “Eaffrey Johnston” that appears in some records, and a lot of biographers confidently state that this is her. There’s no actual “evidence” for that, though. Let’s start over.

Aphra Behn first definitely appeared in England in 1665. She was around twenty-five years old, and claimed to be the widow of a Dutch merchant named Johann Behn. She also claimed to have been born in England, and to have spent several years in the colony of Suriname on the coast of South America. This was an English colony at the time, but they would traded it away to the Dutch in a few years. [2] She might have met Johann there, or maybe on her return to England. At any rate he was dead (if he ever actually existed) by the time Aphra began her service to the Crown.

She was introduced to the court by Colonel Thomas Colepeper, a mysterious figure in his own right. Colepeper had been active in campaigning for the Royalist cause prior to the Restoration of Charles II, and was at the time notorious for his scandalous elopement with a woman “above his station” three years earlier. His exact position in court at this time is unclear, but it seems likely that he was involved in the intelligence service. He was the one who recruited Aphra as a spy, and claimed to have known her as a child. In fact, his book Adversaria (an odd mix of autobiography, trivia, alchemy and engineering) is the only record we have from the time of her childhood. [3]

Aphra was sent to Antwerp, as at the time England and the Dutch were at war over control of the Atlantic trade routes. Her codename was “Astrea”, the Greek goddess of innocence and virginity. Ironically her job was to act as a honeypot, seducing an English exile named William Scot and setting him up for use as a double agent in the Netherlands. It’s possible that she knew William, as he’d previously lived in Surinam. It was a badly managed operation from the start. Aphra underestimated the cost of living in the Netherlands, and soon fell into debt. Her support from London dried up too, possibly due to confusion due to the Great Fire of London which broke out around this time. Or it may simply have been that the Crown didn’t reward failure. The choice of target turned out to be a bad one. William Scot’s father Thomas had been executed for being one of the members of Parliament who had voted for Charles I’s death. His son had no wish to serve the regime that murdered his father. In fact, he may even have betrayed Aphra to the Dutch. This could explain why she was desperate enough to borrow money for a ticket back to London.

There’s a common belief that Aphra Behn was sent to a debtor’s prison on her return to London because the Crown refused to settle her debts. It’s true that a warrant was issued for her arrest, but there’s no evidence she was ever actually arrested as a result. Instead she got into the theatrical business, as a playwright. It was a popular vocation for spies – aside from Christopher Marlowe, Charles II’s “court jester” and probable spymaster Thomas Killigrew was an accomplished playwright. He could have been the one who got Aphra the job. Though she had written poems before, they hadn’t been published. In fact, England had never had a woman who made her living through writing before this. Aphra Behn was about to become the first.

Aphra’s first play went on stage in September of 1670. It was called The Forc’d Marriage, and is a fairly standard love triangle set in the court of an unspecified country. A warrior named Alcippus earns a reward for the king, and asks to marry Erminia, the daughter of the general he he is replacing. However she and the king’s son Philander are in love. The marriage goes ahead but she refuses to consummate it, and Alcippus becomes convinced that she is sleeping with Philander. [4] The two fight and Alcippus strangles her unconscious, but thinks that he has killed her. Erminia then “haunts” him, pushing him into a frame of mind that leads to the happy ending. It’s an interesting play, with an interesting heroine. Erminia takes on a lot more of the dramatic weight than was normal for a female actor (by this point women actually played the female parts). The play ends with “a woman” (probably Aphra herself in the first run) coming out and speaking of how men are clearly the more intelligent gender. The implicit sarcasm here speaks to an undercurrent in the play of “women as property” – all are treated as gifts that can be bestowed out, totally subject to men’s whims. Erminia’s resourcefulness and demonstrated intelligence stand in stark contrast to that.

The play was a success, and Aphra’s share of the take (she got the profits from every third night of performance) helped her to settle her outstanding debts. It was staged at the Duke’s Theatre, and Aphra would write all of her plays for the Duke’s Company who performed in the theatre. The “Duke” was the Duke of York – the King’s brother James Stuart. Aphra’s second play, The Amorous Prince, OR The Curious Husband was staged in 1671. If her first had been a love triangle, this one was a love spiderweb. A vast network of characters seduce or attempt to seduce each other, impersonate one another, and enact complex plots all tied into their amorous desires. It’s a confusing mess, but that’s exactly the point. Once again it was a success, and Aphra even had the honour of her plays being among those referenced and satirised by The Rehearsal, a notorious swipe at the plays of the day that was staged later in the year. The Rehearsal did speak to changing public tastes, however. Aphra’s third attempt to go back to the same well, The Dutch Lover, was staged in 1673 and was a complete flop. It only played two nights before folding – and as a result, Aphra got nothing.

Aphra vanished from the London scene for the next few years, prompting much speculation. Some people even think she may have gone off to work for the King again. The Third Anglo Dutch War had broken out the year before, and her talents would have been useful. It’s also after this that her writing starts to show more hints of spy’s tradecraft knowledge. Alternatively she might have gone away to try and reinvent herself. In 1675 the Duke’s Company put on a play called The Woman Turned Bully, with no author listed. Some scholars think it might have been written by Aphra – her first try at writing a straight (non-dramatic) comedy. If so she might have left her name off it in order to avoid the association if it failed. In fact, it was both a critical and commercial success.

Now all that’s brave and Villain seize my soul,

Reform each faculty that is not Ill,

And make it fit for Vengeance; noble Vengeance!

Oh glorious word! fit only for the Gods,

For which they form’d their Thunder,

Till man usurpt their Power, and by Revenge

Swayed Destiny as well as they,

And took their trade of killing

…

Mischief, erect thy Throne,

And sit on high; here, here upon my head;

Let Fools fear Fate, thus I my Stars defie.

– Abdelezar

Aphra Behn’s definitive return to the stage came in 1676 with Abdelazer. It’s notable as her attempt to correct the racism so prevalent on stage at the time. [5] Many scholars class Aphra as “politically conservative” due to her support for the Stuarts and her refusal to consort with the radicals of the time, but her works show that she was far from socially conservative. Abdelazer takes its story from an earlier play called Lust’s Dominion. In the original play an African prince named Eleazar being held prisoner in a Spanish court manipulates the Queen Mother’s desire for him and the King of Spain’s lust for his wife in order to cause the death of the entire Spanish royal family so he can seize the throne. Aphra’s Abdelazer is a much more sympathetic character, mostly due to his mistreatment by the Spanish court. Though he is a successful general, he is still considered essentially a slave by them. Those critics at the time who disliked Aphra described the work as “plagiarizing” “Lust’s Dominion”, but it would be fairer to describe it as a response to it. Still, it was a commercial success and that was enough to get Aphra back on the map.

Like me? I don’t intend every he that like me shall have me, but he that I like. I should have stayed in the nunnery still if I had liked my lady abbess as well as she liked me. No, I came thence not, as my wise brother imagines, to take an eternal farewell of the world, but to love and to be beloved; and I will be beloved, or I’ll get one of your men, so I will.

– The Rover

Aphra’s immediate followup was The Town Fop, a comedy. But it was her next play that would be her first major success. The Rover premiered in 1677 and was a huge hit. It was a comedy based around four Englishmen who had left England with King Charles II, and who find themselves in Naples at carnival time. Elizabeth Barry, considered to be the first truly great English actress, played the heroine Hellena – a a young girl being sent to the convent who is allowed to attend the carnival by her brother as a literal “farewell to the flesh”. Some historians state that Nell Gwyn (the King’s mistress) came out of retirement to act in the play, but others think this is a mistake based on another actress with a similar surname. Aphra and Nell were good friends – Aphra had poisoned one of Nell’s rivals for the Kings affection with laxatives, and Nell had always worked to raise Aphra’s profile by bringing her friends and acquaintances along to her premieres. The Rover was enough of a success to get an extended run, a welcome windfall for Aphra. She even wrote a sequel (The Rover Part II) that was staged in 1681 featuring the further adventures of the same characters.

Aphra’s success brought her literary credibility, and her ready wit made her popular among London’s artistic scene. She was great friends with many actors and actresses, and her friendship with Nell and demonstrated loyalty to the crown gave her a lot of allies. Of course, it gave her enemies as well, but that was par for the course. There were those who hated the idea of a professional female writer as well, but Aphra’s solid footing in court gave her immunity from their scorn and helped to pave the path for many who followed her. She re-used her spy’s codename as a nom-de-plume for many of her poems, and so her admirers (which included Edward Ravenscroft, John Dryden and Thomas Otway) trumpeted her as “the Incomparable Astrea”.

Aphra wrote several more plays over the following few years. In 1682 one of these landed her in hot water – when Like Father, Like Son was a failure on the stage, Aphra added a prologue to the printed edition denouncing the Whig party, which almost led to her arrest for slander. She evaded jail, but decided to steer clear of the stage for a while – though not of controversy. In 1683 she published her first novel, Love Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister. It was a “roman a clef”, a novel based on actual events with the names changed. Readers would often discuss such novels trying to figure out which real people the characters were based on. In this case, the Nobleman was Ford Grey, the Earl of Tankerville, (named Philander in the text) and the Sister was actually his wife’s sister, Lady Henrietta Berkeley. Scandal, then as now, sold copies.

Then Cloris her fair Hand withdrew,

Finding that God of her Desires

Disarm’d of all his pow’rful Fires,

And cold as Flow’rs bath’d in the Morning-dew.

Who can the Nymphs Confusion guess ?

The Blood forsook the kinder place,

And strew’d with Blushes all her Face,

Which both Disdain and Shame express ;

And from Lisanders Arms she fled,

Leaving him fainting on the gloomy Bed.

– The Disappointment

Aphra followed this up with two volumes of poems. One of the most notable of these poems is The Disappointment, a reworking of a standard parody of the pastorals. In the normal course of the parody a shepherd manages to seduce a young maiden but then, to his shame, finds that he is impotent. Aphra reworks the form by placing it from the woman’s point of view – to have been seduced in this manner, only to be frustrated at the last moment. This sort of inversion was typical of her style. Her work also often included elements of ambiguous sexuality – she wrote love poems to both men and women, while a running theme in her plays seems to be men relying on flirting with each other as a way to “psyche themselves up” to go out and seduce women. She even wrote a poem in which she imagined one of her female lovers as a hermaphrodite. In 1685 tragedy struck, not just for her but for the country. King Charles II died without a legitimate heir, depriving her of a patron at court and plunging the entire country into turmoil as the crown then fell to his openly Catholic brother James II.

He that knew all that ever Learning writ,

Knew only this – that he knew nothing yet.

– The Emperor of the Moon

Though the country was filled with unrest, people still wanted to be entertained. Aphra returned to playwriting, producing A Lucky Chance in 1687. It was a relationship farce with enough sexual frisson to draw the crowds, and paved the way for Aphra’s last big success on the stage, The Emperor of the Moon. In this comedy two daughters plot to get around their father’s strict rules on them dating. He is a keen astronomer obsessed with moongazing, and so they convince him that their two lovers are visitors from the moon. The outlandish costumes, fast-paced action, and adoption of the Italian “Comedia dell’Arte” masked style combined to create something unique in English stage drama at the time. In addition to its popular success at the time, the play is credited with bringing the “harlequinade”, the English cross between pantomime and Comedia, into prominence.

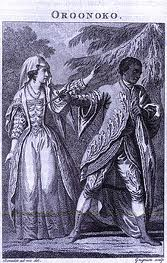

In 1688 Aphra Behn published three novels – The Fair Jilt, Agnes de Castro and what many consider her most interesting work, the novel Oroonoko, or the Royal Slave. The hero is a general of the free Akan kingdoms in South America, the grandson of an African prince. When Oronooko resists the King’s attempt to take his wife Imoinda for himself, he is (along with his wife) sold into slavery in the British plantations in Surinam. There they are reunited, and when Imoinda becomes pregnant Oroonoko is inspired to lead a slave revolt. The revolt fails, and Oronooko kills Imoinda to save her from reenslavement and rape before being captured and executed. The novel includes a prologue where the narrator describes Surinam, and claims the story to come from first-hand knowledge. This led many to believe that the novel was partly autobiographical, though many details are clearly entirely fictitious. The novel wasn’t a huge success at the time. Though it does not explicitly condemn slavery, it does portray slavers as villains and slaves as human beings. Once again Aphra seems to be socially progressive, and politically conservative. The novel was controversial on other fronts – it was definitively anti-Dutch in tone (Oronooko’s revolt and brutal execution take place after the Dutch take over the colony), and the throne of England was now occupied by the very Dutch William of Orange.

Here lies a Proof that Wit can never be Defence enough against Mortality.”

– Aphra’s epitaph.

Aphra Behn died in 1689, aged only 48 years old, after several years of illness. She had been at her most prolific before her death – translating and writing for as long as she could hold a pen. Though she was very out of favour at court, and somewhat impoverished, her death provoked an outburst of popular affection and mourning. She was buried in the cloisters of Westminster Abbey, as was becoming traditional for England’s most beloved poets. One elegy published shortly after her burial captures the public mood. Written by “a young lady of quality”, it mourns:

Let all our Hopes despair and dye,

Our Sex for ever shall neglected lye;

Aspiring Man has now regain’d the Sway,

To them we’ve lost the Dismal Day…

However, the niche that “the Incomparable Astrea” had carved out was to prove a permanent one. Many female playwrights and authors would follow in her footsteps, their profession no longer the scandal it would have been. Yet Aphra Behn herself wound up being minimised, in the centuries to follow. A biography published shortly after her death deliberately sensationalised her life, painting her as a notorious libertine. While it’s probably true that she did have lovers, she was never scandalous about it. (The same biography was also responsible for enshrining the idea that Oronooko was based entirely on Aphra’s own life.) Theatre owners jumped on this image of the lusty lady writer in order to promote posthumous shows of her work. In fact, two plays she had written near the end of her life were only staged after her death.

This same notoriety, however, wound up getting her erased by many later critics. To have such a historically important figure a sexually liberated woman (whose writings were about as rude as any man’s written at the time, but far too rude for Georgians and Victorians) was frankly embarrassing. Meanwhile her strong support for the royal family and the divine right of kings alienated the progressives, causing them to ignore the obvious feminist and anti-slavery messages that her work actually included. Like many unfortunate writers, Aphra was condemned sight unseen by anthologists and critics who took the word of their predecessors as gospel, and never dared sullying it by actually reading what they assured their readers was rubbish. It wasn’t until the 20th century that Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West “reclaimed” Aphra, reinventing her as a symbol of modern feminism. It’s hard to know what Aphra would have made of this, being seen as a precursor. But reading her work, it seems clear that Aphra was well aware of the inequity of the society in which she lived – though her need to make a living often took precedence over that. It was Viriginia Woof, in “A Room of One’s Own”, who paid the most heartfelt tribute to “the incomparable Astrea” for paving the way:

All women together, ought to let flowers fall upon the grave of Aphra Behn, for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] Aphra is a Hebrew name originally, though it was and still is fairly rare. In fact Aphra Behn is the only “Aphra” with a wikipedia entry who isn’t a moth.

[2] They got New Amsterdam in exchange, and re-christened it New York.

[3] Very convenient, if he was helping her set up a plausible past. Colepeper ended his life in a bitter feud with the nobleman who had bought the estate that his wife would have inherited, a feud that saw both of them imprisoned and which left Colepeper too unpopular to get a job at court.

[4] That name isn’t quite as “on the nose” as it might seem. At the time it was a common name in plays for a lover, as it derived from the Greek word for “love”. “Philandering” as a phrase for cheating didn’t come into use until thirty years later, mostly inspired by plays like this.

[5] It’s also notable for the incidental music Henry Purcell wrote to accompany a revival of it twenty years later. Specifically, his rondeau from the Abdelazer Suite is immediately recognisable. This is because it has been frequently used as a theme tune for radio and TV shows.

[6] Whether William was an usurper (as the Jacobites believed), an invited new ruler (as official British history claims), or a foreign military leader who conquered Britain with local help (as most continental histories see it) is left as an exercise for the reader.