The Biology of Luck | book review

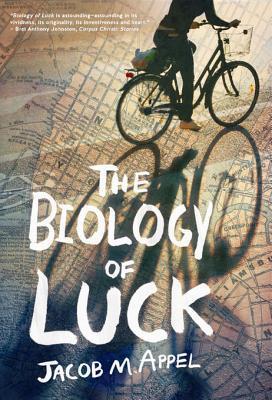

The Biology of Luck by Jacob M Appel. Published by Elephant Rock Books.

The Biology of Luck by Jacob M Appel. Published by Elephant Rock Books.

The slim book (modest at 207 pages) sits on the desk, loaded with promise. The cover is beautiful, immediately appealing — the foreground enigmatic and the background featuring that most familiar of urban street-plans, the grids, letters and numbers of Manhattan. Inside the front cover is a pullout naïf sketch of Larry Bloom’s New York City, the city through which, during one long day in June, he is going to pull the reader helter-skelter, laughing and shaking his head. The quotes inside the cover drip with approbative adjectives; seductive, delightful, complex, outstanding.

The book has a lot to live up to and the first page has not yet been broached.

Larry Bloom is an unattractive, self-obsessed, narcissistic New York Jew. He is very aware of his physical shortcomings; too plain to attract random attention from beautiful women, not grotesque enough to evoke sympathy or pity. Bloom is a true anti-hero. His job as a New York City tour guide allows him to display the worst attributes of his character: leering at a young, teenage girl on the tour-bus, hoping to attract her away from her parents, even while knowing his quest is futile. Despite no hint of evidence of reciprocation he dubs her “the teenage temptress”. When the young girl falls from the parapet of Clinton’s Castle into the boiling waters below, Bloom’s major concern is not for her well-being but for the fact that she is rescued by someone else, someone faster, stronger, braver, thus robbing Bloom of his moment of glory.

There is a scene in an episode of The Big Bang Theory, where Raj hopes to overcome his pathological inhibition and inability to speak in the presence of women. When advised to break himself in gently by first attempting to speak to ordinary people, instead of beauty queens, he replies in tones of horror: “What? Fatties and Uggos?” And that sentiment sums up Larry Bloom’s attitude too. He has no interest in attracting a plain, loving mate who matches his pulling power, he has set his heart upon the most beautiful girl in NYC, a woman with two lovers already and who regards him as a harmless, non-threatening friend.

It may be apparent that I don’t think much of Larry Bloom, and I don’t. If I were to meet Larry Bloom I might give him a swift boot up the ass. He is a deeply irritating character. Bloom, however, is real. He is really real. He is drawn with honesty and integrity, he jumps off the page declaring his veracity and his every tormented action on that fateful day in June reeks of authenticity.

The main female protagonist in The Biology of Luck is Starshine Hart. This is where it gets interesting. Starshine lives through the same day, but she lives it through the pages of a novel, also entitled “The Biology of Luck”, which Larry Bloom has written. He has lovingly, painstakingly crafted a novel about Starshine over a two year period of unrequited devotion, and has submitted it to a publisher. In his top pocket he carries the unopened reply to his submission. We read each chapter of his novel, interspersed with episodes from his day. It is a novel-within-a-novel. The real events of the day weave and intertwine with the imagined scenes from the same day which constitute Larry’s novel. Larry and Starshine duck and dive and almost intersect, the strands of the two concurrent narratives twisting together with the complexity of “…strands of DNA, wrapped and mated to each other to produce a separate entity, a deeper realisation.” (Los Angeles Times).

When reading The Biology of Luck, one is, very early on, struck by the book’s declarative cleverness. The entire structure screams “look at me, look what I have done.” A review by New City on the back cover states “There are not many books like ‘The Biology of Luck‘. Why? Because few authors have the hyper-verbal skills of Jacob Appel.” I, certainly, in a lifetime of reading, have never encountered anything quite like it before. And always, in the back of the mind during the early chapters is the little voice whispering, this is too clever by half, too clever for its own good.

So what do we have: a very clever smart-arse of a book containing two of the world’s most annoying characters. For we have not, as yet, mentioned the other whisper from the little voice. The whisper which increases in volume with every mention of Starshine. Starshine, for frick’s sake… Starshine Hart. For, while Larry is irritating but real, Starshine is irritating and unreal. She could be called a quintessential wank fantasy, but I, being so refined and educated, don’t you know, will call her a pastiche, a conglomeration of every single, lonely, white male’s imaginings of what constitutes a desirable woman. Starshine is beautiful of course, but only after starving and exercising herself to that pinnacle of beauty, shedding 85 pounds of unwanted Starshine to become the radiant creature that she now is (Fatties and Uggos take note). She is sexually voracious, with two lovers and a string of concurrent one-night-stands, but we are assured, it’s alright, because she loves them both, she’s not a tramp, or anything. She gets everything she needs by crying or flirting with whichever man is ultimately in charge of her future destiny. She is damaged enough by a tough childhood to need rescuing, but not damaged enough to be scary or weird. And her final redeeming feature: although she is such a kooky, manic pixie freak chick that she is trapped in a menial, low-paid job because of her refusal to take any job that requires her to wear shoes to the interview, she is also normal and decent enough to understand that she owes her beloved, but senile, Aunt Agatha a huge debt of gratitude and to spend money that she can’t afford, and time that could be spent on self-indulgence, to bring Agatha an extravagant fruit-basket to her nursing home.

The little voice gets louder and louder until we finally ask. What the hell is happening? How can Jacob M Appel, who is widely acknowledged a genius, a man with Masters degrees in writing, law, medicine, a qualified NYC City guide, a practicing psychiatrist and America’s leading bioethicist, a man with over two hundred and fifteen fiction publications in journals including Agni, AQR, the Boston Review and short-listed for every major prize in the field, have written this character? How can he have crafted Larry so lovingly, and have treated Starshine in such a facile and juvenile manner? It just doesn’t make sense.

And then, with the same blushing sense of foolishness that hits the reader at about the seventh chapter of Lionel Shriver’s The post-birthday world, we realise that we have been blind. Despite the notation at the top of every chapter, despite being told, over and over, despite having our faces metaphorically rubbed in it, the realisation finally dawns — moves from the intellectual understanding to the emotional understanding. Yes, we are reading two novels simultaneously, but the two novels have two different authors. The Biology of Luck is written by supreme master word-wrangler, Jacob M Appel and The Biology of Luck by Larry Bloom is written by Larry Bloom. Uh, d’oh!

And it is exactly the book that Larry Bloom, with all his failings and faults would write.

This novel which we have secretly been describing as too clever for its own good, is not that clever at all. It’s much, much more so, it’s the cleverest structure of a book that I think I have ever read. Okay, we mightn’t learn much about Starshine as a real person, but my God does Larry Bloom reveal himself through the pages he devotes to her.

No wonder the back-cover-quoted review by New City ends with the sentence “Stick with this novel, and the reward will be great.” It really does need sticking with, it’s not spoon-feeding anyone, and although Appel is at pains to point out the glaringly obvious, until you get it, you really don’t get it.

I know it is a dreadful cliché, but it would be remiss to point out that among a host of amusing, interesting, often silly, secondary characters, there is one that stands out above the rest. And that is the city itself. It is notoriously difficult to qualify as a registered NYC city guide, and somehow Appel has managed to squeeze that in beside law school and med school and an MFA in fiction. His love for, and knowledge of, the city reeks through every page, bringing scenes to life, laying out the diversity of the city, it’s loveliness and its squalor, its welcome and its utter indifference. His quiet reflections of the futility of modern tourism are gentle, never hectoring, and we are left with a desire to live more fully our future experiences, to stay out of the giant gift shop of life, but to stay longer at the exhibition itself. Appel’s short fiction often includes elements of the surreal and fantastic and although he says that this novel “proved a considerable constraint on my imagination” it still contains wonderful, fabulous elements barely grounded in the possible. And where better to be barely grounded in the possible than in New York City?

The reader of this review will scarcely have missed the parallel between Larry Bloom’s odyssey across NYC and Leopold Bloom’s June day stroll through Dublin, and the two cities play similarly vital roles in each book. Appel’s is an infinitely easier read, though.

It seems churlish to point out, about a novel that beguiled and infuriated me in equal measure, but it is disappointing to note that the book, particularly the latter pages, contains a lot of intrusive typos. Not only the usual suspects it for if, form for from etc, but at one point a surname is spelled differently in the space of three words, a restaurant name is spelled differently twice in one paragraph. On the back cover, the name of the publisher is incorrect. This is not pure pedantry — readers read at the speed of light, transforming marks on a page into a fluent, four-dimensional cinematic event somewhere inside the cortex, and anything that makes the eye stumble, that makes the reader suddenly, sickeningly realise Hey, this isn’t real, this is a made-thing, a construct detracts hugely from the joy of fluent reading. It’s such a shame.

This is a wonderful novel, a deep, unflinching gaze inside the prosaic, mundane soul of a modern anti-hero with a powerful message about institutionalised patriarchy and misogyny, where all value is based on beauty, desirability, transience and unrealistic hope.

Or….

You can dismiss the crazy ramblings of a middle-aged feminist and read it, and enjoy it hugely, as a slightly offbeat, beautifully written rom-com, as many reviewers online have done, and have a pleasant romp through NYC in the company of a bunch of irritating, but charming, no-hopers.

Either way, it’s well worth the read.