Review | Montpelier Parade by Karl Geary

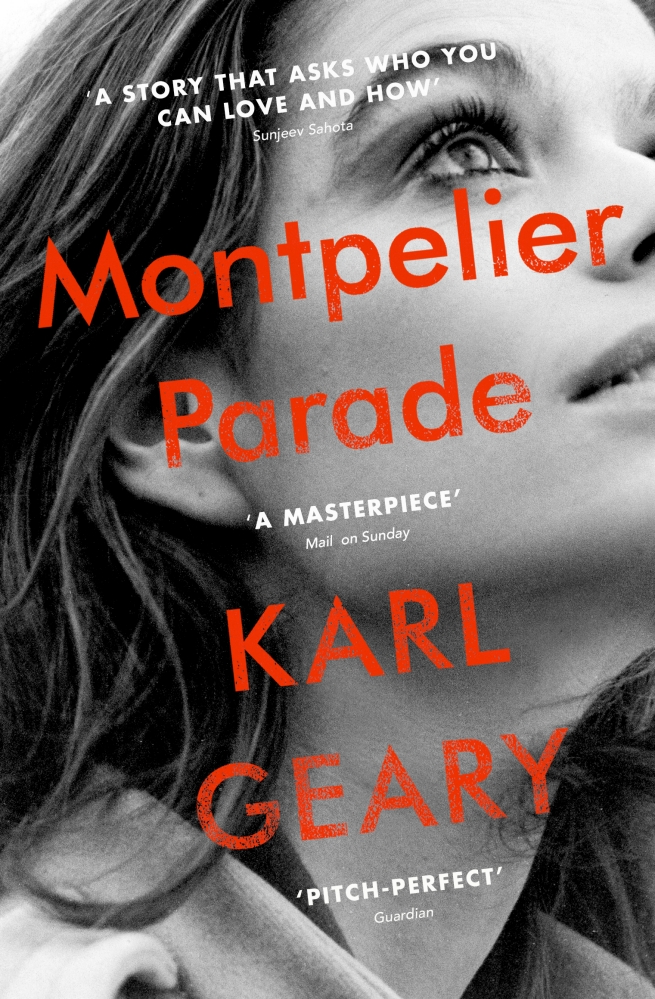

Montpelier Parade, the debut novel by Irish-born American author Karl Geary, was published by Harvill Secker just over a year ago, in January 2017. Its name is now quietly bubbling to the top of many ‘best books of the year’ lists, making the shortlists for the Sunday Independent Newcomer of the Year and the Costa First Novel Awards.

The story takes place in 1980s Dublin, following adolescent Sonny Knolls through his work at a butcher’s shop and weekend labour with his gruff father, all the while trying to keep his head above water at school. His world is predictably thrown into chaos when he meets Vera, a beautiful older woman from a wealthy part of town, on a job with his father. It’s a typical doomed romance story with a few nice little twists and turns thrown in.

The narrative is written in the second person, so Sonny is the ‘you’ through which the story unfolds. We’re strapped straight into his head and shown the world through his eyes, and whereas this can be jarring and downright horrible to read if not done well, Geary manages it with such a light and adept touch that it’s difficult to imagine it working better any other way. The only other novel I’ve come across to manage it so well in recent times is Ablutions by Patrick deWitt (HarperCollins 2009).

If Geary’s writing style were a person, you’d say they haven’t a pick on them. It is clear, direct, and slim – not unlike Sonny’s characterisation – all of which leads to an excellent pacing and a relatively short, enjoyable read. It feels like an older man sitting down to write a story from his youth, to convince himself it all actually happened, and he didn’t just dream it up. The book is quite tender as a result. Not tears running down your cheeks tender, more of the melancholy sigh variety, but what a lovely sigh it is.

If Geary’s writing style were a person, you’d say they haven’t a pick on them. It is clear, direct, and slim – not unlike Sonny’s characterisation – all of which leads to an excellent pacing and a relatively short, enjoyable read. It feels like an older man sitting down to write a story from his youth, to convince himself it all actually happened, and he didn’t just dream it up. The book is quite tender as a result. Not tears running down your cheeks tender, more of the melancholy sigh variety, but what a lovely sigh it is.

There were times where I found myself crying out for some love handles to grab onto, so to speak; for a bit of meaty indulgence. While this does come through in some parts, I would have liked more visceral passages like the schoolyard fight that crescendos: “You smashed his face and felt nothing for the pain he felt, even when he dropped to the ground […] as if you yourself had never felt pain in your whole life.”

If Montpelier Parade is a little light on action, it is heavy on emotion, especially the unspoken Irish variety, and it’s to the author’s credit that there’s so much to read between the lines. I find that an Irish book of any quality has at its heart a mastery of this form of understated communication, of which Anne Enright is currently the paragon. That Sonny is the battleground through which his parents converse – his brothers literally ignoring their father’s existence – will be familiar to most people whose mother and father talk to each other through their children. Geary manages this delicate waltz brilliantly, and his portrait of a working class Irish home is painfully accurate.

While this is one of the finest things about the book, and about modern Irish literature generally, it is also the reason why I find myself able to read an Irish novel only every now and again. As an avid reader, I’m convinced no one does misery quite like the Irish. I once asked a secondary school English teacher if he could suggest any horror books for me, to which he replied, “I don’t need to read horror, I work in an Irish public school.” Similarly, I’m too familiar with quotidian Irish misery to seek it out as regular escapism, which was why I studied French literature to explore a sunnier form of sadness and maladjustment.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”#3534DB” class=”” size=””]Geary writes with an almost disturbing insight into family dynamics and sexually-charged relationships.[/perfectpullquote]

None of this is to detract from Geary’s novel, of course. He creates a world that is tearfully real yet somehow ethereal; it often feels as if Vera’s house on the eponymous Montpelier Parade will go the way of the House of Usher. The author threads some lovely themes through the narrative, such as what the class divide might mean if taken to extremes, with Sisyphean manual labour on the one hand, and sedentary hedonism on the other. Even suicide, in this context, can be seen as a luxury for the upper classes.

The most fully realised motif is that of the bike that Sonny is building in his shed from spare and stolen parts. We know he’s saved up some money and could probably just buy one, yet he persists in stealing parts in order to build the bike. It’s a little difficult to penetrate the logic at work here, but perhaps it’s that stealing a part is better than stealing the whole thing. Doubtful, perhaps, but then we’re not imprisoned in Sonny’s world, one where he must hide books from his family lest they think he’s getting notions.

Geary writes with an almost disturbing insight into family dynamics and sexually-charged relationships. The characters are at their most vivid precisely in their interactions with each other, which I find to be a major feat and one of the book’s most admirable aspects. While we’re inside Sonny’s head throughout, the other characters feel just as real to us as he does, as he tries, often in vain, to penetrate their thoughts and motivations.

All in all, Montpelier Parade is an excellent read and well worth picking up, and Karl Geary is an author to watch out for. You’ll be enchanted with his wonderful writing but be warned, you’ll likely find your misery meter reaching critical before the end.