Books are not Dead Things

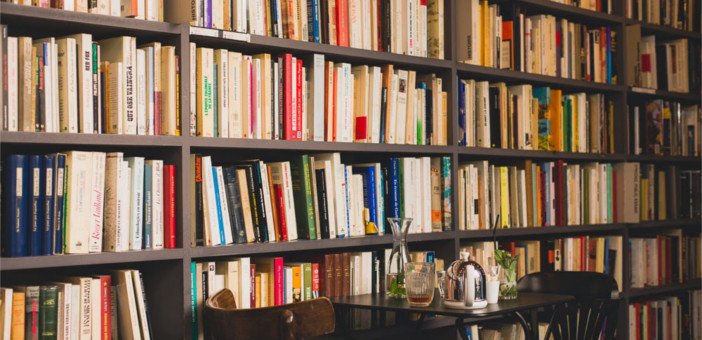

Recently, I visited a café in south county Dublin and noticed that the walls were decorated with shelves chock-full of books. Piles of them, literally, ten and twelve high in some places. They were all hardbacks of a certain era – 1940s/50s ? with those faded green and roseate cardboard covers. I wondered how they had been chosen. Was it for their content? Or was it the pretty colours of their covers, their forlorn vintage chic, that complemented the lime-washed New England décor of the café? I took a look at some of the titles – The Whiteoaks of Jalna by Mazo de la Roche was one. De la Roche was a Canadian writer, who penned a 16-novel family saga over a 30-year span from the 1930s to 1960s about the eponymous Whiteoak family. They were common currency in my convent school library in the 1970s. We discussed their plots with the enthusiasm now reserved for selfies and You Tube clips.

The Jalna novels were what you might call polite bodice-rippers. Lots of heaving bosoms and unrequited love but the bedroom door invariably closed at the opportune time. Georgette Heyer was another staple of our school library. These were solid, middle-brow novels, well-researched and historically accurate with doughty female heroines. Heyer was reduced to shelf fodder in this café too. So were several Reader’s Digest compendiums of abridged books that seemed to cluster in the holiday chalets of my childhood. Seaside reads, in other words. But, here’s the difference; we actually read those books when the rain came down and there was nothing else to do but stay indoors.

I’ve revisited this café several times and I’ve never seen anyone take down one of these books. That’s not the deal. They’re for decoration. They’re literally part of the wallpaper. They are books chosen on a “never-mind-the quality-feel-the-width” basis, displayed for the sole purpose of projecting a brand – we’re bookish, we’re hipster, we’re cool, we’re vintage.

[pullquote] Home décor websites are a hotbed of this kind of objectification of books. One such site offers 37 different ways to decorate your home with books. Cut a hole in the middle of a thick volume, put earth inside and plant something in it! Why not pile your books up and make a bedside table of them? Tear out the pages and make a fabulous collage![/pullquote]A friend instanced another example from a pub in Dubai. The interior had the look of a book-lined study but on closer inspection, the books – yes, real genuine books – had been chopped in half vertically so that they would fit on the narrow shelves assigned to them in the pub’s design.

In the hey-day of the reconstituted “Irish pub” – when they sprouted in Beijing, Boston and Baden-Baden – ye olde family photographs were used in the same way, bought in bulk by pub outfitters to give the dewy-eyed exile the impression he/she was walking into Granny’s kitchen back home. The trouble with these artefacts is that for someone somewhere they are genuine mementoes representing real human relationships. Like the books, they have authorship.

Home décor websites are a hotbed of this kind of objectification of books. One such site offers 37 different ways to decorate your home with books. Cut a hole in the middle of a thick volume, put earth inside and plant something in it! Why not pile your books up and make a bedside table of them? Tear out the pages and make a fabulous collage!

But before the interior decorators got their hands on the book, its value among so-called book-lovers was already declining. Some years ago I was a judge on a major literary competition and ended up with over 100 contemporary novels, many of them hardbacks, which I couldn’t accommodate on my shelves. They were brand-new publications, hot off the presses, in mint condition, yet I had real difficulty finding a home for them. My first port of call was my local second-hand bookstores. I felt sure of a welcome there with my glossy, almost new, library. These people were my own kind, weren’t they? But they turned out to be annoyingly finicky. Some wouldn’t touch hardbacks; others cherry-picked the big names from my crates and rejected the rest. I even tried the local library. The librarian on duty looked at me askance as if I were trying to peddle drugs when I offered them four boxes of brand new books. Where would we put them, she demanded in an almost aggrieved tone. I stopped myself from suggesting the obvious. In the end most of the books ended up in a charity shop, the only place that would accept them no questions asked. Oh, apart from the dump, that is.

But I couldn’t contemplate that. Even though these books represented imposed reading rather than titles I had chosen myself, I had never considered simply throwing them out. But maybe I should have. Isn’t pulping and recycling a more honourable end for the unwanted book than being transformed into a cute planter or deconstructed into a fabulous collage? And there’s always the possibility of a reprieve at the dump. Another acquaintance of mine goes to the dump for all his reading material. He climbs into the large bin for paper and cardboard and scavenges merrily. I imagine him like a vineyard keeper trampling on grapes at harvest time, high on the fumes.

The downgrading of the physical book is inevitably twinned with the digitising of reading. Amazon has been blamed for devaluing the book by merely pricing it down to the cost of a sandwich. Independent publisher Dennis Johnson, proprietor of Melville Books, declared in an interview in the New Yorker last year, that Amazon had “successfully fostered the idea that the book is a thing of minimal value – it’s a widget”.

The physical book was declared obsolete when e-books first came on the scene. But this prognostication has proved premature. E-book sales have settled at around 30% of the market, so that means that 70% of us are still buying the physical object.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m no Luddite. I have a Kindle and do a lot of reading on it. But when I like a book, really like it, I go out and buy it in a bookshop because I don’t feel I own it when it’s trapped, incorporeal, in an electronic device. I need to see it on a shelf where I can put my hand on it. That’s probably an indication of my age – anyone born in the 1950s probably relates this way to books. The Kindle is efficient, convenient and portable, but for me, it lacks the objecthood and temporality of the physical book. I’m a sucker for the texture of a leather-bound hardback, for the luxury of marbled end papers or the crinkly freshness of a volume with uncut pages. I could go on. . . but I won’t. It sounds too much like breathless porn.

But there’s a difference between my kind of bibliophilic fetish, and an interior decorator pimping out books as deconstructed decorative objets. For me, the cover and binding is only part of the relationship with the book, not the be all and end all. As Milton observed in Areopagitica, his impassioned argument against censorship way back in 1644, books are “not absolutely dead things”. They contain the “potency of life in them to be as active as that soul was whose progeny they are; nay, they do preserve as in a vial the purest efficacy and extraction of that living intellect that bred them”.

Hands off our books, I want to say to those café owners, interior decorators and pub designers keen to fill up empty visual spaces, they’re for reading.

Featured image:

dailyhomedecorideas.com

bp.blogspot.com

crunkletonblog.files.wordpress.com

10best.com