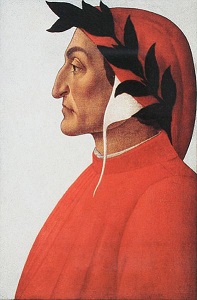

Dante Alighieri, Florentine Exile and Writer

Nowadays Dante Alighieri is primarily remembered as the author of the Divine Comedy, but there was a lot more to him than that. Politician and poet, he ended his life in exile from a city which he had once ruled. He elevated the language of the common man in order to give literature to the people, and laid the foundation stone that Italy’s Renaissance would be built upon.

The exact year of Dante Alighieri’s birth isn’t recorded, but it’s been estimated as being around 1265 by working back from the age he gave for himself later in life.

His father, Alighiero di Bellincione, was either a moneylender, a lawyer or both. Either way he was a solid middle-class professional, active in politics without being prominent enough to suffer consequences when those politics turned nasty. At the time there were two political factions in the independent Italian city-states, reflecting the two poles of power they were caught between.

On one side were the Ghibellines, who supported the Holy Roman Empire. [1] On the other side were the Guelphs, who aligned themselves with the Pope and more generally with the idea of autonomy for the city-states. At least, that was the theory; by the 13th century they had become basically fronts for local rivalries and power-broking.

That didn’t make the battles they fought any less vicious though, with thousands being killed in the Battle of Montaperta five years before Dante was born. Like most Florentines his father was a Guelph, and Dante would be raised in that faction as well.

Little is recorded of Dante’s childhood, but three incidents stand out. The first was the death of his mother, Bella, when he was nine or ten years old. Dante was the only child of his parents, but his father would go on to have two more children with another woman. (Whether he married her or not is unclear, as widowers remarrying was a dubiously legal concept at the time.)

The second was Dante’s own marriage, which he was contracted for aged 12. (As with most of his class, this was an arranged marriage to cement family ties.) His fiancee was Gemma di Manetto Donati, the daughter of a prominent politician. The third was that when he was nine years old his father took him to a party at the house of Folco Portinari, a banker who lived near them. Folco had a daughter named Beatrice, who was the same age as Dante, and the moment he saw her he fell in love.

It’s difficult to tell how much of Dante’s history with Beatrice is real, and how much is fictionalised by him later to fit her “role” in his work. By his own admission, he barely knew her. At the time this type of admiration from afar was known as “courtly love”, though to the modern eye it seems more like stalking.

At any rate, he says that he next met her nine years later, when they were eighteen. In the intervening years Dante had frequented areas where he might catch sight of her, but this was their first interaction. She spotted him, recognised him, and said hello. That was enough to send Dante into rapture, and that night as he slept he had the vision of:

…a mist of the colour of fire, within the which I discerned the figure of a Lord of terrible aspect to such as should gaze upon him, but who seemed there-withal to rejoice inwardly that it was a marvel to see. Speaking he said many things, among the which I could understand but few; and of these, this: “I am thy Lord”. In his arms it seemed to me that a person was sleeping, covered only with a crimson cloth; upon whom looking very attentively, I knew that it was the Lady of the Salutation, who had deigned the day before to salute me.

And he who held her held also in his hand a thing that was burning in flames, and he said to me “Behold thy heart”. But when he had remained with me a little while, I thought that he set himself to awaken her that slept; after the which he made her to eat that thing which flamed in his hand; and she ate as one fearing.

After that encounter Dante never met Beatrice again, though she haunted his thoughts and his writings. He married Gemma (who he never wrote about) two years later in 1285, and they had at least three children. Beatrice married in 1287, and then died in 1290. From these two brief encounters with a woman he didn’t know, Dante created an entire character; an ideal woman untainted by any actual hint of her own personality beyond his imagining.

He himself referred to her as “my glorious lady of the mind”, “my beatitude, the destroyer of all vices and the queen of virtue, salvation”. The real woman barely matters except as the framework for this symbolism.

Love’s fire is kindled in the gentle heart,

As virtue is within the precious stone;

From out the star no glory doth depart

Until made gentle by the sun alone.

– Al cor gentil rempaira sempre amore by Guido Guinizelli

There was more to Dante’s life than his obsession with Beatrice, of course. He had friends and mentor, a group who he would retroactively label as the founders of the dolce stil novo (the “sweet new style”). The forerunner of this “style” was Guido Guinizelli, whose poetry was deeply influential to Dante. Guido (who died when Dante was ten or eleven years old) wrote poems that emphasized the transformative nature of “feminine purity” and the pure spiritual nature of love for such a woman as a gateway to the divine; along with a deft touch for metaphors. Both of these became the foundation of Dante’s personal aesthetic.

Dante also included in his stilnovisti his friend Guido Cavalcanti, who was both a poet and (very unusually for the time) an atheist. Guido’s father was notorious for practising the Roman philosophy of Epicureanism, a materialistic belief that denied the ability of the divine and the supernatural to affect the world. It’s likely that this was what caused Guido’s own beliefs, and it’s a sign of how powerful their family was that they got away with it. Guido’s atheism allowed him to take on board influences from Islamic poets and philosophers such as Ibn Rushd (who the Italians of the time called “Averroes”). This was an influence that he passed on to Dante to create a truly trans-Mediterranean sensibility.

By some one I was recognized, who seized

My garment’s hem, and cried out, “What a marvel!”

And I, when he stretched forth his arm to me,

On his baked aspect fastened so mine eyes,

That the scorched countenance prevented not

His recognition by my intellect;

And bowing down my face unto his own,

I made reply, “Are you here, Ser Brunetto?”

– Inferno

Dante’s mentor was Brunetto Latini, a respected diplomat and high-ranking Guelph. He was one of the preeminent lawyers of the city, as well as a respected politician and powerbroker. He may have been Dante’s guardian after his father died, and when Beatrice died he told Dante to read the Roman writer Boethius to console himself.

The philosophy of Boethius, that the world could only make sense if viewed in relation to God, was another major influence on Dante. Despite this close friendship though, when Dante wrote his masterwork he was forced to place Brunetto in the third circle of Hell as a “sodomite”. He was notorious in Florence for his homosexuality, and to fail to condemn him for it would simply have invited questions.

In 1289 Dante was one of the young Florentine men who fought in the Battle of Campaldi, when the Guelphs of Florence and the forces of the Kingdom of Naples defeated a Ghibelline army and ensured that Florence stayed purely Guelph. Of course, since those factions had merely stood in for local rivalries it wasn’t long until the Guelphs split into “White Guelphs” and “Black Guelphs”.

Ostensibly the White Guelphs promoted Florentine independence while the Black Guelphs aligned themselves with the Pope, but of course it was just another excuse to manouevre for advantage. Dante involved himself in politics (which bizarrely required him to register himself as a pharmacist since you had to be a member of a guild to hold public office). He was a White Guelph, and helped in the coup that expelled the Black Guelphs from the city around 1300. Following this he was named one of the nine priors who were the governing council of the city.

In order to try to defuse the tension between the leaders of the factions in the city their leaders were temporarily exiled by the priors. This included Dante’s friend Guido Cavalcanti, who contracted malaria shortly after leaving the city and died. Dante blamed himself for his friend’s death. All of this also created some tension with the papacy, and so Dante was part of a delegation sent to Rome to try to determine the Pope’s true intentions.

And he cried out: “Dost thou stand there already,

Dost thou stand there already, Boniface?

By many years the record lied to me.

Art thou so early satiate with that wealth,

For which thou didst not fear to take by fraud

The beautiful Lady, and then work her woe?”

– Inferno

The pope in question was Pope Boniface VIII, whose desire to return the papacy to its old status as a major power would eventually lead to his death. Dante was the casualty of the Pope’s ambition, though at first it seemed like favouritism when he was asked to stay in Rome to argue his case while his fellow delegates were sent home. In fact it was a pretext to keep him from the city in case he had learned anything of the Pope’s plans.

For this treachery Dante would later place the Pope in the 8th circle of Hell, though since Boniface was still alive in 1300 when the poem was set he had to use the dodge of having someone mistake him for Boniface and declare he was there too early.

While Dante was away Charles of Valois, the younger brother of the King of France, led an army into the city and violently placed the Black Guelphs into power. Dante’s property in the city was confiscated and he was charged with corruption from the time he had served in government.

He was sentenced in absentia to exile until he paid a massive fine; one that he would not pay on principle and could not pay in practice because his money had been confiscated. He would never return to the city he loved.

At first he tried to return. He allied with Scarpetta Ordelaffi, a former captain of the Ghibellines, and they tried both diplomatic and military action to return to Florence. The former was laughed out by the Black Guelphs while the latter ended in bloody fashion at the Battle of Lastra with the death of four hundred of the exile army.

After this Dante became a nomad of the Italian cities, staying in Romagna, Padua and various country estates belonging to sympathetic nobles. It was around this time that Dante began work on his masterpiece, an epic which he called simply Commedia.

Commedia is of course better known nowadays as “The Divine Comedy”, but the adjective “Divine” was added after Dante’s death. Commedia consists of three volumes, the first and most famous of which is Inferno. It is set on the night before Good Friday in 1300, and tells the story of how Dante is lost in the woods and being hunted by wild beasts when he is rescued by the ghost of the Roman poet Virgil. Virgil tells Dante that he has been sent by Beatrice to guide him on a journey, and that the journey begins at the gateway to Hell.

“Through me the way is to the city dolent;

Through me the way is to eternal dole;

Through me the way among the people lost.

Justice incited my sublime Creator;

Created me divine Omnipotence,

The highest Wisdom and the primal Love.

Before me there were no created things,

Only eterne, and I eternal last.

All hope abandon, ye who enter in!”

– Inferno

The Hell described in Inferno consists of nine circles. The first of them is Limbo, where the ghosts of those who lived righteous lives but were not Christians (like Virgil) live in pleasant green meadows, not tormented but not permitted to enter heaven. Here Dante describes meeting classical philosophers and rulers who lived before the Christian era as well as those Muslims who the people of his era considered “righteous” (like Ibn Rushd and Salah ad-Din).

The other eight circles are each dedicated to a family of sins; such as Lust, Gluttony, Violence and Wrath. Through his journey Dante meets figures from both ancient and recent history being punished for their sins, with each punishment symbolically appropriate for the sin in question. Dante uses this device to give his own commentary on the politics and events of the day.

Notable is his scathing disregard for the Church; several popes are residents of the Circles with the eighth (Fraud) having an entire district reserved for those who sold ecclesiastical office and favours. (They get placed head-downwards in tubes that resemble baptismal fonts and have their feet roasted with fire.)

The nine circles of Dante’s hell form the structure of an inverted cone, a funnel which dives deeper and deeper into the earth. As he moves inwards, he also descends. The fifth circle is the river Styx, where the wrathful fight each other on the shore and the sullen are submerged in the water.

Keeping this water back from falling into the sixth circle is a great wall forming the demonic city of Dis, which Dante only passes with the aid of an angel who tells the guardians that he is on a divinely appointed journey. This division marks the passage from what Dante considers “physical” sins (like Lust and Gluttony) to spiritual sins (like Heresy and Treachery).

The Emperor of the kingdom dolorous

From his mid-breast forth issued from the ice;

And better with a giant I compare

Than do the giants with those arms of his;

Consider now how great must be that whole,

Which unto such a part conforms itself.

Were he as fair once, as he now is foul,

And lifted up his brow against his Maker,

Well may proceed from him all tribulation.

O, what a marvel it appeared to me,

When I beheld three faces on his head!

– Inferno

Treachery is the ninth circle, at the centre and bottom of hell. Here the traitors are imprisoned in a lake of frozen ice, denied warmth as they denied the warmth of the bonds they betrayed. At the centre of this lake is the ultimate sinner, Satan, who directly betrayed God himself. Unlike portrayals that show the Devil as ruling over an infernal kingdom Dante’s Satan is trapped waist-deep in the ice and suffering for his sin.

Dante describes him as a giant beast with six flapping wings and three faces, with the three men who Dante considers the ultimate human traitors clasped in his jaws. One is Judas Iscariot, the other two are Cassius and Brutus; the men who organised the murder of Julius Caesar. Dante and Virgil then pass downwards from Satan, through the centre of the Earth and climb up to the Southern Hemisphere where they emerge into the light of day. [3]

The other two books of Commedia are Purgatorio and Paradisio. Though less famous than Inferno, they are almost as influential. In Purgatorio Dante and Virgil travel up the spire of Purgatory which is divided into seven terraces for each of the deadly sins. At the top of the spire is the Garden of Eden, where Paradise touches the earth. In this book the theme is repentance rather than punishment, with those whose sins were minor purifying themselves before they enter heaven.

Dante’s politics are even more in display here, as he is able to place those he respected and was friends with undergoing their penance before their reward. This is also where Dante meets the dead poet Bonagiunta Orbicciani, who congratulates Dante for he and his friends having created Dolce Stil Novo: the “sweet new style”.

Like sudden lightning scattering the spirits

of sight so that the eye is then too weak

to act on other things it would perceive,

such was the living light encircling me,

leaving me so enveloped by its veil

of radiance that I could see no thing.

– Paradisio

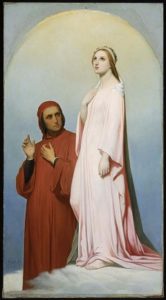

Paradisio is perhaps the epitome of that “sweet new style”. Virgil being unable (as a pagan) to enter Paradise, it is Beatrice who takes over as Dante’s guide for the final part of his journey. In this book the theme is perfection, and Dante (through the characters and setting) lays out his vision both for the perfect society and of the factors that corrupt that society.

As with the previous two books Paradise is divided into sections, but this time they are based on the six known planets (up as far as Saturn) plus the sun, “fixed stars” and “moving stars”. The sections for the planets are based on their classical symbology (so Venus represents Love, for example) while the “fixed stars” are the ideal church (as distinct from the corrupted church of Dante’s time) and the “moving stars” are the angels of heaven.

Beyond them lies the Empyrean, where Dante sees God. The book ends with Dante having a moment of insight where he finally understands the relationship between mortal and divine love.

As influential as the contents of Dante’s epic would be, even more influential was a single unique quality about it. Prior to this written works in Italy had always been in a classical form of Latin, though the people across the peninsula used a variety of local dialects which had mutated and evolved over the last thousand years.

Dante broke with tradition by writing Commedia in the common language, and specifically in his native Florentine dialect. He did this out of a belief that literature should be available to all, and that the use of Latin had become a deliberate barrier to the common people. Over the years to come Commedia would become the basis of written Italian, and the foundation of Renaissance literature.

Dante did not live to see his work achieve the status of classic, though. Most of Commedia was written in the city of Verona, where he found sanctuary with the lord Cangrande della Scala. It was because of this that Paradisio was dedicated to Cangrande.

In 1315 Dante was offered a pardon and the chance to return to Florence. To take advantage of it he would have had to perform a public penance, which he refused to do so he remained in exile. In 1318 Dante moved to the city of Ravenna, where he completed the Commedia in 1320. The following year he contracted malaria, and he died at the age of 56. He was given a state funeral and buried in Ravenna.

Dante had a contentious relationship with the church (a treatise he wrote in 1318 denounced the idea of absolute papal authority, for example); and so his son Pietro was always afraid that Commedia might be denounced as heretical. Its literary importance overshadowed that though, and so apart from a few bans over the decades it was largely accepted.

In 1348 the Florentine writer Giovanni Boccaccio wrote a laudatory biography of Dante, rehabilitating him in Florence to such an extent that they even asked Ravenna to return his body so that he could be buried in his native city. Ravenna refused to do so, but in 1519 Pope Leo X gave an order for the body to be moved to Florence. To prevent this the Franciscan monks who tended his tomb removed and hid his bones. They were restored to the tomb in 1781, but then in 1810 when the French occupied the city it was feared that Napoleon would take them so they were hidden again.

In 1865 a workman restoring the convent where they were hidden found the box containing the bones, and a young student realised what they were. The bones were put on display for a few months before they were buried once again.

When mechanical printing arrived to Italy, Commedia was one of the first works printed in 1472. As the Renaissance blossomed in Italy so Commedia inspired artists and other writers alike.

From the beginning it was always the florid imagery of Inferno that caught people’s imaginations, rather than the more cerebral Purgatorio and Paradisio. By 1555 the book had become known as La Divina Comedia di Dante, and it was recognised as the genuine Italian national epic. It remained little-known in the English-speaking world until the 19th century, when it was translated into English and inspired works by artists like William Blake and Dante Gabriel Rosetti.

Writers as diverse as Karl Marx and TS Elliot quoted Commedia in their writing, and films and music have also been inspired by the work. In modern times Dante even had the dubious honour of having Inferno adapted into videogame form. Nearly 700 years after they were written, Dante’s work is still a touchstone of modern culture; a testament to the power of the words of the Florentine who died in exile.

Images via wikimedia.

[1] Despite the name, the Holy Roman Empire was actually to the north of Italy and was primarily composed of modern Germany.

[2] Dante believed in the ideal of Italian unity, and so he is punishing the men who killed the man who would have been the first ruler of that country.

[3] Dante, like all educated men of the medieval period, was well aware that the earth was round.