The Double Demise of England’s New Yorker

Punch magazine shared several qualities with US publication The New Yorker; it was celebrated for the quality of its cartoons, it featured humorous writing from contributors known on both sides of the Atlantic (most notably PG Wodehouse) and, for a short, inglorious period it even impersonated its New York cousin. Sadly, though, it eventually folded – folded twice, in fact – and, as we’ll see, I may have played a small part in its final demise. But let’s begin at the beginning, which is a very long time ago.

Punch magazine shared several qualities with US publication The New Yorker; it was celebrated for the quality of its cartoons, it featured humorous writing from contributors known on both sides of the Atlantic (most notably PG Wodehouse) and, for a short, inglorious period it even impersonated its New York cousin. Sadly, though, it eventually folded – folded twice, in fact – and, as we’ll see, I may have played a small part in its final demise. But let’s begin at the beginning, which is a very long time ago.

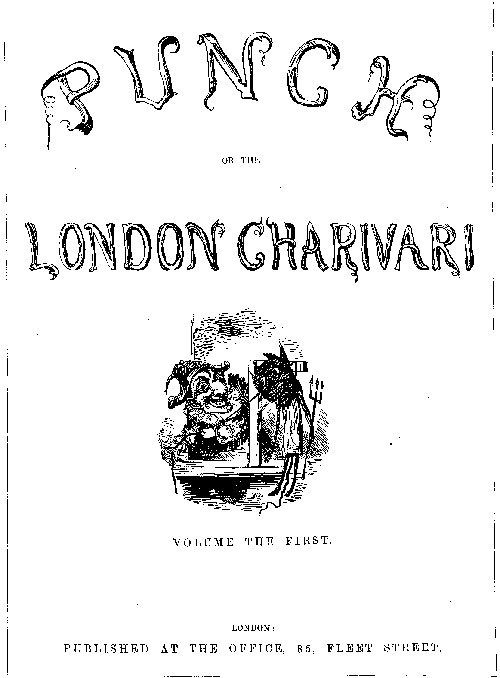

Punch magazine was born in 1841. Mr Punch was its symbol from the first issue, but the magazine got its name because its founders, Ebenezer Landells and Henry Mayhew, wanted it to be a heady mixture, like a good bowl of punch. And, after all, didn’t their chosen editor – Mark Lemon – share his name with an essential ingredient of punch? How they must have roared…

Punch magazine was born in 1841. Mr Punch was its symbol from the first issue, but the magazine got its name because its founders, Ebenezer Landells and Henry Mayhew, wanted it to be a heady mixture, like a good bowl of punch. And, after all, didn’t their chosen editor – Mark Lemon – share his name with an essential ingredient of punch? How they must have roared…

Their new satirical publication got itself noticed yet even in its early days sales were disappointing, averaging only around 6000 a week. The publishers thought up the clever wheeze of devoting an issue to a review of the year – the first Punch Almanack – and sales shot up to 90,000. One of the main contributors to that first Almanack, Harry Grattan, wrote his material while banged up in the Fleet debtors’ prison; how’s that for a whiff of Dickensian authenticity?

In the UK, the very mention of Punch suggests mid-Victorian stodginess but in fact, as befitted a magazine born in the decade of the Chartists and the 1848 revolutions, its early agenda was markedly radical. In 1843 it published a verse polemic by Thomas Hood entitled ‘The Song of the Shirt’. Hood wrote the piece after discovering that a seamstress would only be paid five farthings for her work on the shirt he’d just bought. Even today, of course, the media still expose exploitation in the clothing trade. Everything has changed since Punch’s early days and yet everything is still the same.

Radical campaigning zeal and big-selling Almanack editions couldn’t lift the magazine out of its early troubles and in 1843 the title was taken over by the publishers Bradbury and Evans; they retained ownership until 1969 (126 years!) when, as Bradbury and Agnew, they sold out to United Newspapers.

The magazine’s radical edge quickly mellowed and by its supposed golden age in the late 1800s Punch still poked fun mildly, but was very much part of the establishment; every country house library, every cabinet minister, every diplomat had their bound copies of Punch.

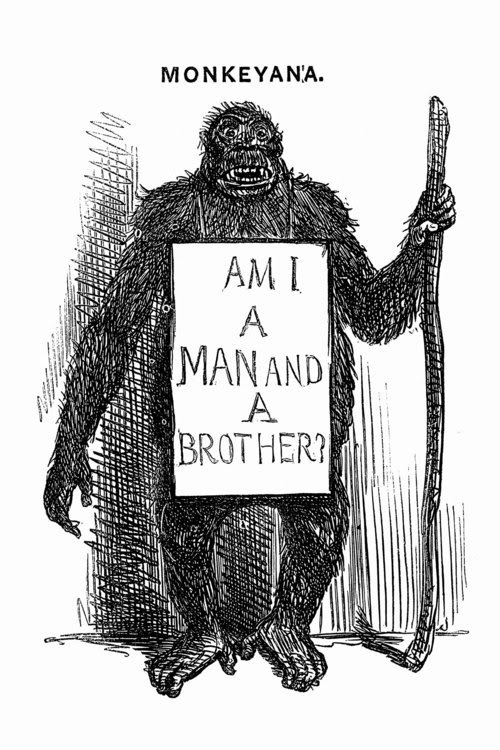

Which is not to say that the magazine wasn’t innovative; the use of the term ‘cartoon’ to mean a simple, humorous line drawing was coined by Punch, and from the very first some of the best artists worked on the magazine; Leech and Tenniel in the Victorian era and the likes of Trog, Fougasse, Ronald Searle and Gerald Scarfe in the twentieth century. Until the 1900s, the magazine referred to the main political drawing as ‘the cartoon’.

Which is not to say that the magazine wasn’t innovative; the use of the term ‘cartoon’ to mean a simple, humorous line drawing was coined by Punch, and from the very first some of the best artists worked on the magazine; Leech and Tenniel in the Victorian era and the likes of Trog, Fougasse, Ronald Searle and Gerald Scarfe in the twentieth century. Until the 1900s, the magazine referred to the main political drawing as ‘the cartoon’.

Writers such as Thackeray, AP Herbert and PG Wodehouse contributed to the magazine, but when Miles Kington – a Punch staffer in the 1970s and 80s – edited an anthology in 1998, the vast majority of the work he included came from the post-war period, long after the supposed golden age of Punch. Surprising? Actually, Kington was probably right in his introduction when he said of earlier Punch writers and cartoonists that, ‘Yes, they drew and wrote beautifully. No, they don’t seem that funny any more.’ Tastes, of course, change. The 19th century editors of Punch are a forgotten band, except for one who retains some minimal fame, especially in the USA, for a macabre reason. Tom Taylor helmed the magazine from 1874 to 1880, but long before that he had been a prolific and successful playwright. He penned around 100 works, none of them performed nowadays, but one, Our American Cousin, was the play Abraham Lincoln opted to go and see at Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865…

In the earlier Punch cartoons the captions were created first by the magazine’s writers, with the artists brought in merely to illustrate them. These captions were often lengthy dialogues involving several characters and the artists were really on a hiding to nothing. It was well into the twentieth century before cartoons became snappier and were fully credited to the cartoonist.

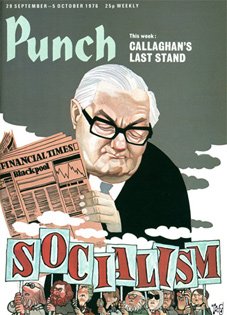

In the twentieth century, Punch seemed bumptiously anachronistic, something that might have been edited in a London gentlemen’s club. To an extent it was, since the bibulous Punch lunches were an important part of the magazine’s production for over a century. ‘Gentlemen! The cartoon!’ was the concluding toast. Guests were often invited to the lunch and many made their mark on the famous Punch Table. The first woman to be invited was Margaret Thatcher in 1975; an odd choice for a comic magazine given that her supporters and detractors alike agree that she had no sense of humour.

Editors occasionally tried to give the magazine more bite; in the 1950s, Malcolm Muggeridge reintroduced traditional Punch satire and in the 1970s, William Davis brought in serious editorials and articles about current events and politics. This latter policy hardly helped Punch in its struggle to be funny. In 1978 Alan Coren, a much-loved humorous writer in the UK, took over the editorship and for ten years the magazine’s circulation slide was arrested and the laughs flowed again. Topicality survived only in articles taking sideways looks at unusual news stories. No more thundering editorials about Apartheid or the IMF.

Even so, by then the standard wisdom suggested that Punch was only ever read in dentist’s waiting rooms. Perhaps there was some truth in this, yet the magazine remained an enjoyable read, perfect for an hour’s train journey (in Scottish terms, say, Glasgow to Perth) or for a short suburban trip delayed for 40 minutes owing to overhead line problems. And someone must have been buying it or advertisers wouldn’t have used it to promote upmarket clothes, accessories and holidays, the kind of stuff you may have seen closer to home…

I was a student in Glasgow, Scotland, in the late 1970s, far in every way from Punch’s London Clubland core market, yet it still managed to amuse me. I loved Alan Coren’s imaginative flights of fancy, Miles Kington’s clever wordplay and the earthier work of Keith Waterhouse. Punch still thought of itself as satire, but any fun it poked was gentle. Few targets were offended and none lost office as a result. This restrained gentlemanliness was mocked at the time (dentists’ waiting rooms, etc) but in a crueller age it feels like we’ve lost something valuable.

I was a student in Glasgow, Scotland, in the late 1970s, far in every way from Punch’s London Clubland core market, yet it still managed to amuse me. I loved Alan Coren’s imaginative flights of fancy, Miles Kington’s clever wordplay and the earthier work of Keith Waterhouse. Punch still thought of itself as satire, but any fun it poked was gentle. Few targets were offended and none lost office as a result. This restrained gentlemanliness was mocked at the time (dentists’ waiting rooms, etc) but in a crueller age it feels like we’ve lost something valuable.

I longed to be a part of it. Not just shelling out 50p (or whatever it was) each week, but a contributor, someone adding to the heritage of gentle humour that stretched back to 1841. But the regular writers were an exclusive lot, mostly from English public schools and Oxbridge. There were some writers from northern England, like Keith Waterhouse, but they’d all long since fled to the Smoke. The reviews section was full of good writing but barely admitted the existence of the arts outside London.

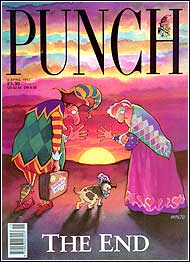

Yet there was a minor Scottish toehold on the magazine, in another feature shared with The New Yorker; the caption competition. In the Punch version, a cartoon from the Victorian era was reproduced, captionless, and readers were invited to supply a new one. The mysterious C Thomson of Glasgow dominated the contest. Could another low-born Scotsman hope to break into the pages of this upper-class, English, London institution? The question became academic when tumbling sales figures claimed their victim. In 1992, Punch folded.

In September 1996, however, the magazine re-emerged (or, perhaps, unfolded). Fuelled by large sums from Harrods’ owner Mohammed Al-Fayed, the new Punch, though still very London in outlook, had a different feel. Its look was quite openly modelled on The New Yorker and so was the content, with short stories becoming a regular feature. I examined it hungrily, since I was now a part-time freelance writer. The content did not impress; it looked like The New Yorker, but it didn’t read like it. Surely I could do better than this dross? At the time I was working on an affectionate but light-hearted article about the little-known (outside Scotland) sport of shinty. I polished it to suit the Punch style and sent it away. They accepted it and asked me to invoice them for £400.

Four. Hundred. Pounds.

I sent them the invoice with frightening speed, and also humbly offered them another article (a eulogy to a fondly remembered trash TV game show It’s a Knockout – the US version was Almost Anything Goes). I was phoned a few days later and told that the Knockout article, too, was accepted. In due course I would be asked for another invoice. I started tinkering with a resignation letter to my employer. Boy, that letter told it straight.

Every Friday I checked the latest Punch and every time returned it to the shelf; no shinty, no Knockout. Then I read a news item about the editor of Punch being ‘removed’. Alarm bells. I phoned the editorial office and none of the people I’d spoken to hitherto were, ahem, ‘available’. I was told someone would get back to me.

They did get back to me, by letter. The shinty piece did not meet the needs of the new editor, it seemed. But the £400 cheque was enclosed anyway.

The important (to me) matter of the Knockout article remained. Further enquiries established that the new editor was changing the look, style, content and target audience of Punch. The Knockout piece no longer pressed the buttons, but they’d pay me a £200 kill fee. Being £600 up on a deal has never been so depressing.

The new-style Punch duly hit the newsstands: I understand it featured some investigative reporting but was otherwise relentlessly downmarket. The New Yorker presumably breathed easily again, rid of its incompetent imposter. I could never bring myself to look at the wretched revamp, and never submitted any more work.

I was never able to sell the shinty article: my first impressions of the original relaunch had been right and their quality control was suspect. The magazine folded again in June 2002. I wonder if the £600 I squeezed out of them might have helped them avoid the bullet? Did I help to kill an English institution?

I was never able to sell the shinty article: my first impressions of the original relaunch had been right and their quality control was suspect. The magazine folded again in June 2002. I wonder if the £600 I squeezed out of them might have helped them avoid the bullet? Did I help to kill an English institution?

The Punch cartoon archive is the only surviving part of the magazine; it’s a commercial concern and online you can order prints and other goodies featuring classic Punch cartoons. It’s no consolation, for I never got to see my name in Punch and now I never will.