Bicycles and Blues | Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman Turns 50

From its broadest strokes to its tiniest details, Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman is built out of weirdness. Weirdness is not only its dominant style but its very element, its operating logic, its final destination, and its means of getting there. The book, which was first published fifty years ago, proceeds according to a manic, self-updating logic that is entirely its own. Nothing like it has appeared in Ireland before or since. It is either our jokiest masterpiece or our most masterful joke. Then again, in Flann O’Brien’s hallucinatory universe, the distinction hardly matters.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”#3535DB” class=”” size=”18"]To describe Policeman as a single novel is perhaps to do it a disservice. It is really a compendium of hundreds of unrealized novels[/[/perfectpullquote]p>

Policeman is short on plot but heavy on atmosphere. Its narrator, a nameless, wooden-legged scholar, spends much of the story wandering around a fictional parish, somewhere in Ireland, having nonsensical conversations with mad sergeants, ghosts, and murderers, often revolving around the topic of bicycles. As a point of fact, he is himself a murderer. At the beginning of the novel, he is persuaded by a friend to kill a miserly old man, and then to steal his savings. The execution is carried out flawlessly, and yet, like an Irish reincarnation of Raskolnikov, he never quite gets around to retrieving the money. Instead, he finds himself drifting through an increasingly surreal world, fashioned out of sin and guilt. Soon he begins to question the whole order of reality, and seeks solace in the bizarre, anti-scientific writings of his favourite thinker, an obscure Continental philosopher named De Selby.

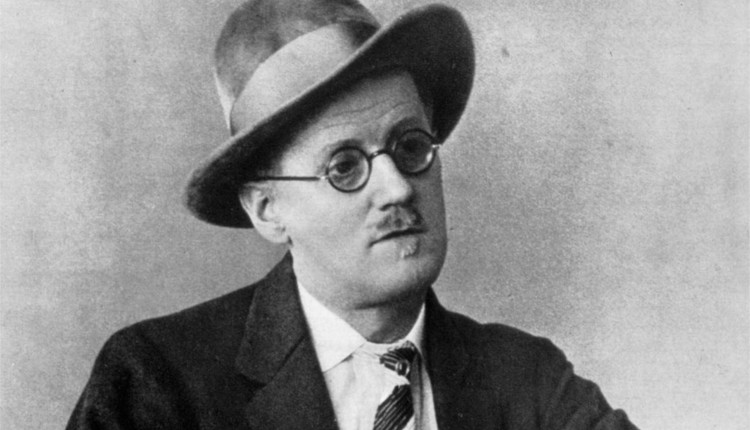

It might sound like a mess, and maybe it is, but the confidence of the author’s vision, and the lightness and precision of his prose, keep even the wildest digressions in check. It is a prose that is conversant with two traditions, I think. The first, and more obvious one is that of Irish satire, and Policeman is indeed filled with the inheritances of Swift, Sterne, Wilde, and Joyce.

The lattermost, above all. There are moments in the novel when the narrator seems to channel Joyce’s famously overripe lyricism: “Birds piped without limitation,” he declares, in a burst of ecstatic description, “and incomparable stripe-coloured bees passed above me on their missions.” Now, is that bad pastoral writing, or a parody of bad pastoral writing? Or is it a parody of Joyce’s parodies of bad pastoral writing? Only Flann knows for sure, and though his style might be safer, and friendlier, than his hero’s, it builds up into a similarly confounding mixture of sobriety and whimsy, irony, gravity, and misdirection.

As well as the intimidating prose style, what O’Brien shares with Joyce is an apparently limitless imagination. To describe Policeman as a single novel is perhaps to do it a disservice. It is really a compendium of hundreds of unrealized novels, all of them eager for dominance. Other stories, or potential stories, are always flaring up through its pages like bright shapes doubled in windows. They are glimpsed in the form of reveries, hallucinations, newspaper clippings, anecdotes, oddball theories, and hearsay. At one point, the narrator imagines a series of names for himself, each one redirecting him to an alternate life. When he thinks of the name Signor Beniamino Bari, he is immediately carried away by dreams of some “eminent tenor” singing before a crowd in Rome. His daydream is transcribed, Joyce-like, in the form of sickly journalese: “As he warmed to his God-like task, note after golden note spilled forth to the remotest corner of the vast theatre, thrilling all and sundry to the inner core.”

But O’Brien is no mere transcriber of dreams. As well as being a trickster, a comedian, and a raconteur, he is a supreme artist; his visions, no matter how demented, are always bundled up judiciously in a stable, finely sculpted shell. The last time I read Policeman, it made me think of that Hieronymus Bosch painting, The Garden of Earthly Delights. The triptych, as you might recall, looks like the world’s least enjoyable Where’s Wally? scene, a vast panorama of heaven, earth and hell, populated by demons and tormented souls, as well as creatures that must be seen to be believed (in the Hell section, a poor woman is molested by something that appears to be half-tree, half-astronaut). But if you fold over the two outer panels, closing the picture in on itself, you will find that the artist has produced a secret image on the back, the earth: a cool, careful, silent sphere, afloat in space. The question seems to be: How can something so pretty contain such chaos?

[p[perfectpullquote align=”left” cite=”” link=”” color=”#3535DB” class=”” size=”20"]he narrator’s mind is, arguably, somewhat bicyclic, or bicycloid, in its workings, with his consciousness and his conscience ticking together in unison, under the meaty extertions of a removable body. [/pe[/perfectpullquote]

Policeman has something of a Boschian structure to it. Behind all the pageantry and farce, the book contains its own secret images. O’Brien’s fictional landscape, for all its silliness, is really a dark, austere place, filled with vulnerable souls who are always running up against the spectacle of the inhuman. There is something eerie in the way O’Brien’s descriptions of nature tend to slip out of their frivolous clothes, becoming by the full stop naked, blank examinations of an unpeopled world. And the way his characters often switch, midway through conversation, from a colloquial register to a highly theoretical and cerebral one; this is amusing at first, and then disturbing. And the way those conversations always seem to return to the relative safety and beauty and meaning of bicycles is also, in its way, unsettling. It is as if there is only one soul in this world, endlessly dispersed, trapped in many bodies. Again and again, whimsy tips over into horror. The innocuous is always growing fangs.

In one extraordinary scene, the narrator pays a visit to one of the local policemen, MacCruiskeen. Apparently a carpenter by hobby, MacCruiskeen produces for his visitor a little wooden chest; it is “beautifully wrought”, with “the dignity and satisfying quality of true art”. He opens the chest, revealing a slightly smaller replica inside. He takes this second one out and opens it. Sure enough, it contains a third, even smaller chest. He opens that one; a smaller chest comes out. “That was very competent masterwork” the narrator remarks snidely. But as MacCruiskeen’s chests become ever punier, eventually reaching submicroscopic, even subatomic levels of littleness, the narrator grows proportionately uneasy. At some point, the scene departs from the realm of social comedy and enters the void of cosmic horror. “What he was doing,” the narrator insists, “was not wonderful but terrible.” By the end, he can hardly bring himself to look at the assortment of dust-sized chests. He tries to hum an old song instead, if only to be consoled by a “human noise.”

Which brings me to the other tradition with which I think O’Brien is engaged, namely the Russian one. If the American novel, for example, has always been obsessed with dreams of plenty, with destiny and opulence and self-invention, then the Russian novel has over the centuries dealt with the inversion of those things. Poverty. Meaninglessness. Self-cancellation. Absence in all its sizes. If we stretch the definition to include Kafka, who was Russian in temperament if not by birth, then the influence becomes clearer. These days, Flann O’Brien is more often celebrated as a funny-man than as a serious writer, but Policeman’s comedy is the not the comedy of Roddy Doyle and Father Ted. Rather, it is the comedy of Notes From Underground and Dead Souls and The Trial, which is to say, the weirdest, least consoling kind. The laughter it releases is neither warm nor pleasant; it is closer to the howl of the condemned man, the killer, the lunatic, or to the nervous chirruping of its own narrator, for whom the impossibility of the tiny chests seems to signify the contingency of reality and the absurdity of existence.

It would be unpropitious of me, if I may bend my language momentarily towards O’Brien’s, to conclude here without pausing to consider what role the bicycle plays throughout these fictitious escapades. I’ll risk stating the obvious and say that this most graceless of objects, with its ungainly mechanisms and rusty rhythms, are to O’Brien’s novel what the figure of the white whale was to Moby-Dick, a grand, unifying metaphor around which the narrative prowls and curls, and towards which the characters’ thoughts are forever drifting. Perhaps it is to be understood as a psychological symbol. The narrator’s mind is, arguably, somewhat bicyclic, or bicycloid, in its workings, with his consciousness and his conscience ticking together in unison, under the meaty extertions of a removable body.

At any rate, O’Brien seizes upon his two-wheeled metaphor with such strange power and inventiveness that he succeeds in doing something remarkable; he estranges the ordinary. After you read this book, go outside and watch your neighbour sail down the street on her dainty Cannondale. Does the scene not have a freshly monstrous aspect? Do those handlebars not suddenly loom like horns? It was once said of David Lynch that his success lay not in the quality of his nightmares, but in the skill with which he transferred them. His dreams have become everyone’s dreams. In the right hands, even the most ridiculous of images – a bicycle, say, reimagined as a sinister, metaphysical instrument – can become radiant and infectious.

Lately, for all the fashionable talk of a literary revival, the Irish novel has been preoccupied with the narrowly social. To engage with the newest “original young voice” is more often than not to endure a familiar gallery of miserable families, bad farms, emigration papers and council estates. Some of this stuff is quite good, of course, and the novel is a spacious and generous form; there is room within it for all these things. But The Third Policeman seems to me like the last major attempt by an Irish writer to reinvent the contemporary, to mutate and surrealize it, rather than merely reflecting it. In this essential novel, Flann O’Brien is constantly swerving around the speedbumps of his time, searching for greater things, peddling towards eternity.