Fortnightly Fiction | All Hallows’ Eve

The Vandalised Tapestries, Leitrim’s home-grown alternative country rockers, attracted a smaller crowd to the main stage than Veelox did at the other end of the park. For how many years now it was like this. Due to subtle repeated social processes this event was considered the norm, yet still most denizens of Drumshanbo (anyone who was not one of his contemporaries, essentially) believed it to be a decidedly curious and unnatural case.

The teenage illusionist stood on his facsimile stage, from which he engaged this evening’s revellers with his classic theatrical persona, so unlike his usual introverted and mundane self. For almost ninety minutes his entertainment had both encapsulated and terrified the locals.

The sun had set. By his request the floodlights above were non-operational, leaving the audience shrouded in a cloak of darkness, save for the occasional overhead heaters which were distributed randomly across the pitch and offered a tenebrous afterglow. The stage itself was illuminated by a selection of kerosene lamps. Traditional circus music emitted from the speakers set adjacent to both sides of the stage. Those present were on average younger than their counterparts on the other side of the green.

When away from the stage, removed from his act and dissociated from his alter ego, his name was Chandler Cloud. He rose to prominence within the quaint hamlet by making the same promise every year: his All Hallows’ Eve performance would rank superior to anything he ever delivered before. It was never made clear whether this was a commitment made to himself or the townspeople. Regardless, there was a unanimous understanding that it was a promise which was consistently kept.

This pledge was advertised in the pamphlets distributed by a group of enthusiasts past the midnight hour in clandestine fashion at the beginning of every October. Originally, the loyal followers solely comprised of his fellow schoolchildren. As Chandler grew older, his developing act gained more and more traction each year, and other residents of Drumshanbo dedicated themselves to act as messengers on his behalf.

Anyone who lived in the area knew what to expect: familiar crumpled pieces of yellow paper filled to the brim with penny arcade imagery and big bold zebrawood typeset reminiscent of the great European travelling circuses so popular around the fin-de-siècle with their freaks of nature, dead walruses hailing from below the St Pancras underground and all other manners of quirks and oddities on perpetual display for the self-appointed curious.

With each passing year, the receivership of such an advertisement was countenanced with a prevailing conflation of anticipation and trepidation – the slow evolution of Chandler’s magic saw a graduation from common parlour card tricks to an esoteric and arcade variant of illusionism, from the exhibition of which the audience perceived a real risk. Whether this was a risk applicable to themselves or the magician was, once again, unclear. Such a pervasive ominous feeling did little to thwart the cult following, with many considering attendance of the festival a matter of tradition.

Had one acted as an event organiser or community volunteer earlier that day, one would have no doubt overheard the reminisces of previous magic shows and speculation in relation to what the townspeople would be treated to – or subjected to, depending on whom one was eavesdropping – later that evening.

Of particular conversational focus was the respective finales of the previous three years, which had left those present to witness it bemused, befuddled and willing to believe in magic, unable to explain the visual and auditory wonders conjured up for them, despite half of Veelox’s persona being built on rationalism and scepticism, ‘everything performed tonight is designed to arouse in viewers a convincing sense of verisimilitude but I assure you there is no such thing as magic, only sleight of hand, misdirection, and innumerable tricks of the mind.’

Three years before, Veelox returned to the stage after the intermission, announced his finale, waited for the lights to come on and began to levitate, which impressed those in the audience who had never seen anything like it before, but for others, for those with more experience, it felt uninspired. They were ready to give up on him only for the stage below him to start levitating as well under his deft, artful command.

The year after that, each audience member woke up the next morning unable to remember whether or not a finale had even taken place, only to realise over the course of the next few days that every single member of the audience was hypnotised – going home to sleep was the final act.

Last year, every drink on the pitch was turned into wine, even those present for the Vandalised Tapestries on the other end of the venue.

According to alleged confidantes, Veelox had a particular respect for children, who he believed were much more adept to discovering the hidden secrets of his tricks due to their simpler, more binary mind-sets. Teenagers and adults were more likely to overanalyse and obfuscate the most obvious answer for themselves. He would often tell audience members that if anyone ever wanted to know how a magician pulls off the seemingly impossible, rely on Occam’s Razor.

Noticed throughout the day was the growing presence of national broadcaster television crews and presenters. They were surely here for one reason only. Because of this, audience participation, even the punctuated rounds of applause and cheering, were more vehement than ever before, coming off as mildly burlesque or artificial, those complicit aware of the fact that this could be Chandler’s window of opportunity to come to national attention.

Chandler himself was brought into this world with an introverted and diligent nature, and it was common knowledge throughout the community that he spent most of his time residing in his bedroom, studying magic, practicing tricks, perfecting his act. Social interaction with the lad, who, for all intents and purposes appeared to live in a world of his own dominion, was commonly regarded as a laborious if not futile task. Despite this, his guaranteed slot at the annual festival meant that once a year, those who would normally steer away from him if unfortunate enough to end up on the same street, would instead foster in their hearts a gargantuan appreciation for his character and dedication and would look forward to whatever he had up his sleeve this time round.

Despite the bravado of his aficionados, his performance thus far this this evening was rather lacklustre. The intermission lights undimmed, and he trotted onto the stage in an idle fashion. For a second he seemed lost up there, as if he had forgotten his own function. His was an unimposing figure, and in the bright light provided now by the footlights which were recently turned on, one could make out the aquiline shape of his nose, and the void where his missing front tooth should be, having accidentally knocked it out by falling onto a pot plant at a very young age while practicing one of his earliest magic tricks. These constituted the two physical traits local folklore ingrained into the mythology of his character, offering a rationalisation for his reclusive livelihood.

All eyes were on him, waiting for his next move, as if time itself was transfixed by the possibility of what would happen next.

“This is my final trick of the night”, he announced sullenly, staring at the ground. For the first time in his illustrious career, it seemed like regular Chandler was up onstage, as opposed to Veelox.

As if he became acutely aware of this at exactly the same time as his audience, Chandler perked up slightly, fixing his posture and allowing his face to flush red. He walked back to the microphone and, putting on a rather high-pitched voice, said “Welcome to our junior infants’ presentation, we hope you enjoy it.” He gaily glided to the wings of the stage, past the curtains where no one could see him, and re-emerged with a step-ladder and a backpack, though to many in the audience this front appeared a weak veneer, one he could not hold for long. All spectators present were aware that the finale was underway. Any conversational murmurings ceased. Everyone was watching now, waiting for the magic.

Chandler liked to begin in a rather unassuming and lackadaisical fashion, tending to turn inwards towards the trick itself rather than engage with the audience, a practice he regarded with disdain, according to those aforementioned alleged confidantes, of the stark belief that the trick should always be able to speak for itself. On this particular occasion, however, he held his microphone in one hand as he positioned the step-ladder at the back of the stage, up against the wall.

“The origins of All Hallows’ Eve can be traced back to the Celtic festival of Samhain, Summer’s end, though cases have been made for Paganist influence and the legacy of Parentalia, respectively. It was seen as a liminal time, when the spectral line, always so fine, between the living and the dead was blurred, and local folklore would have you believe the spirits, on this night, could traverse from their realm to ours.”

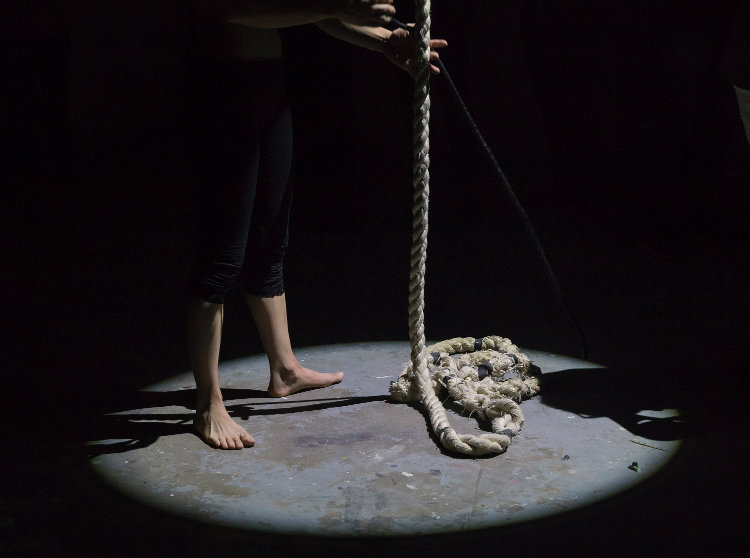

It became apparent he was creating a hangman’s knot, as he repeatedly wrapped loops around the noose he had fashioned while he was speaking. He looped the top of the rope around a hook on the wall, and stood on the step-chair surveying his creation with his back turned to the audience as if figuring out what there was left to do.

He brought the microphone up to his mouth and said “For my next trick, we will discover if a member of the living can visit the land of the dead.”

Chandler let go off the microphone so that it fell and hit the floor of the stage, creating a negative feedback loop with the speakers, causing an uncomfortably loud sound which amplified incrementally, People grimaced and groaned and blocked their ears with their hands. As they did so, Chandler pirouetted upon the step-ladder, manoeuvring his head through the rope so that it came to rest around his neck. He kicked the step-chair backwards, forcing his body to reckon with gravity in servitude of his audience. His descent ended almost as immediately as it began, his body kept from making contact with the ground by the rope, due to which a gratuitous, cringe-inducing snapping of bone was emitted above the deafening feedback, in response to which some of the locals screamed, gasped, welched and vomited. Mothers instinctively reached to cover or avert the eyes of their children. As the microphone was situated underneath Chandler’s feet, the audience could hear his breathing and grunting, which slowly transformed into a steady, prolonged groan. The spotlight which shone down on him from the floodlights emphasised the pallid complexion of his face. Even hanging from a rope, his three-piece suit, shiny shoes and black tie were all still in place, as were his large hands, his gaunt and svelte fingers, which were so necessary for his theatrical gesticulations, giving the impression this was all part of the plan.

“I can’t watch!” someone exclaimed, perhaps for the benefit of everyone else who was rendered speechless. Chandler’s facial muscles exuberated a look of pure concentration, a psychological flow state. Under the spotlight he slowly lost colour, perhaps turning slightly blue, less human. He desperately raised his arms, grappling at the portion of the rope wrapped around the front of his neck, and proceeded to wrangle with it, failing to reach above his head and hoist himself upwards. The futility of such an endeavour was plain for any bystander to see, all spectators automatically assuming this exasperating performance was all part of the nerve-wrecking finale. His groan was louder now, and his attempt to pry the rope away from his neck or at least relax the pressure with which it was fastened around him had resulted in a momentum of sorts building up, as he swung viciously back and forth not unlike a pendulum.

“When was the last time you heard him breathe?” asked someone near the front. Chandler’s eyes seemed as if they were close to popping out of his head. He assailed the rope with apoplectic passion, his body rocking backwards and forwards, faster, a greater distance each time. His legs began to trash madly underneath him, kicking the air as if hoping to land on steady footing, searching for the step-ladder. His eyelids clenched tightly shut. Twisting fiercely in all directions now as the rope rocked from left to right, a miniature makeshift monochrome hurricane amidst strobe lights and dry ice. Someone whispered “Good grief.” His hands clutched to the rope and seemed to relax slowly before his arms gave in to gravity’s demands. His incessant groaning ended, as did the frantic movements of his legs and torso. There, likely a meter above the stage, he swung to and fro for several minutes, opening his eyes when the motion stopped completely. He hung there, suspended in mid-air, gazing vacantly at the audience, who were sitting, simply sitting there in silence, total, unequivocal silence, save for chattering crickets, stifled breaths, the low hum emitting now from the speakers which had come so close just moments ago to blowing completely, and an icy gust of hibernal wind that seemed to choose the perfect moment to strike, all waiting, waiting for the reveal, the great reveal, the ever promised, ever delivered, perennial reveal, it was a trick, and then a slow clap, that’s right, a slow clap, follow uniform until all around, sighs of relief, it was all just a trick. Yes, the audience contracted amongst themselves in unspoken unison, their latent applause could wait until then.